Whether this is new to you or you’re already an expert, I can bet that you’ve been witness to (or victim of) the Dunning-Kruger effect. This unfortunate phenomenon occurs to nearly everyone who gains some knowledge in an area they are passionate about. In 1991, two researchers at Cornell University discovered there is a cognitive bias that occurs when people with limited knowledge or skills in a particular area overestimate their abilities.

In other words, you do not know what you do not know.

In the study, uneducated individuals had higher levels of confidence when compared to professors and professionals. Anecdotally, you see this happen on universities as 18-year-old freshmen absorb newfound knowledge and begin preaching it around campus. In his book “The Death of Expertise,” Thomas Nichols tells a story of a young undergraduate talking with a professor about his theories in physics at a lecture. After a short back and forth, the student says, “well, I guess your guess is as good as mine.” Laughingly, the published author, doctor, and paid professional speaker responds “No, no, no… my guesses are much, much better than yours.”

Over a decade ago, while working on my Master’s thesis covering the impact of warmup modalities on performance, I began connecting the dots between some of my athletic training/sports medicine courses and my desire to be a strength and conditioning coach. At this time in medieval sports performance history, many high school and college programs still utilized bodybuilding splits as their training philosophy. This segmented the body into upper, lower, and individual “muscle” training components. Thankfully for me, through the internet (pre-Instagram), higher level coaches who applied more holistic training styles began to make an impact—long before the phrase “fascia” was on every fitspo’s page, I had read about tensegrity, which describes how the body’s internal structures work together. Physical therapists would use this knowledge to explain how damage in one area can cause pain in other regions, even if unrelated.

As I began working with more athletes, I observed that those who performed large-chained exercises felt and did better than those who stuck to more traditional weight training. Even in strength sports, I was performing full-body splits and making faster and healthier progress than when I did specific lift or body-split days. Since this was my early Dunning-Kruger phase, I was certain I’d discovered the missing link in sports performance training. I could even summarize it into that one specific and unique word: Tensegrity.

One afternoon, talking with an engineering buddy of mine, I was blabbing about how my industry is behind. Many coaches I met did not know about my word of the week. My big, smug smile was met by an eyebrow raise before he let me know that he too knew about tensegrity, providing a much smarter-sounding definition: “tensile strength, or a system of isolated and compressed components within a network of chords that are under continuous tension.” He continued to explain that without it, most bridges, giant towers, and even stadium roofs could not support themselves. Then he showed me an example of tensegrity tables that look like they are floating on wires but can hold HUNDREDS of pounds of weight.

Apparently…I still had a lot to learn.

What Is Tensile Strength

Around 90% of all muscle injuries are strains, meaning the tissue has been stretched or even torn during the loading process.1 At the top of list of strained muscles sits the hamstring, with between 13%-29% of all professional non-contact injuries.2 If an architect kept designing bridges that collapsed under stress, they would quickly find themselves jobless (or in jail).

In the world of professional sports, where millions of dollars are at stake, we do not see the same accountability. As strength coaches and sports medicine practitioners, we cannot control everything—but, we should be able to reduce the risks in our program. Tensile strength is the maximum amount of stress a material can withstand before breaking when its pulled or stretched. This includes soft tissue like muscles, ligaments, and myofascia.

Tensile strength is the maximum amount of stress a material can withstand before breaking when its pulled or stretched. This includes soft tissue like muscles, ligaments, and myofascia, says @endunamoo_sc. Share on XFor most objects, the tensile strength can be affected by the direction of load: for example, muscles have higher tensile strength for forces that parallel the fibers as opposed to those that interact perpendicularly. Most human muscle is extremely strong, meaning a strain or tear requires a lot of force happening at the wrong time and place. One study found that just 9mm of a hamstring graft has the tensile strength of 4,360N or 980lbs.3 That is a little bit of muscle for a whole lot of weight.

If the human body is as resilient as it seems, my question is: how in the world are these high-level athletes succumbing to these season-altering injuries every single year?

Tensegrity for the Strength Coach

When most people hear that less than a centimeter of muscle can withstand over 900 pounds of force, they might wonder how injuries could ever happen. Once we add in the knowledge that a foot impacting the ground at max sprint speed has the potential to be over 1,000 pounds on contact, it starts to make more sense. When we think of biomechanics, we can break it down into two categories:

- Kinetics, which is the study of external forces on the body.

- Kinematics, which is the study of movement based on these forces.

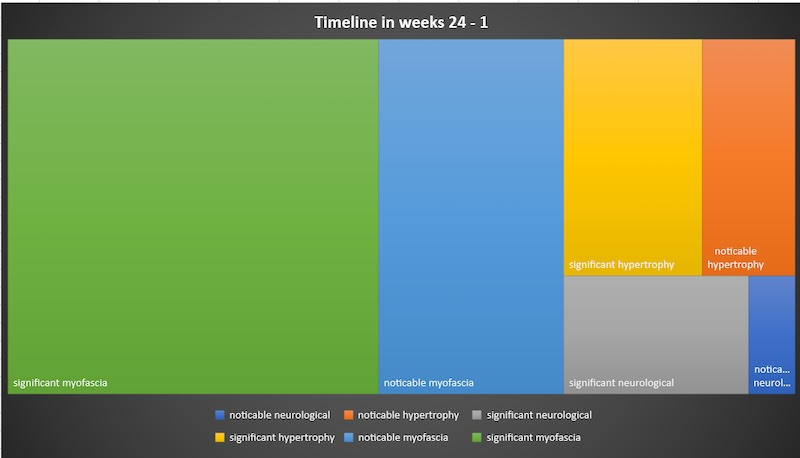

This concept has been referred to as the kinetic chain by many and it alludes to the adage “a chain is only as strong as its weakest link.” If a piece of connective tissue (fascia) is unable to manage the load put on it—BAM—there goes the season. This can occur due to existing trauma, repetitive poor mechanics, or an acute situation. Strength coaches must also examine the adaptation timelines of the body. Significant neuromuscular adaptations (strength) can be seen in as few as 2 weeks, with even greater changes each sequential week; and, then, significant hypertrophic changes by the 4th week.4 With connective tissue, on the other hand, changes occur much more slowly, with noticeable changes occurring at the 3- to 6-month mark and significant development typically happening after 6 months.5

Our muscles out-pace their connective components by 4 to 6 times, creating a real imbalance in athletes. Even more confounding is that connective tissue also detrains at a faster rate than its muscular counterpart, says @endunamoo_sc. Share on XThis means that our muscles out-pace their connective components by 4 to 6 times, creating a real imbalance in athletes. Even more confounding is the current understanding that connective tissue also weakens (detrains) at a faster rate than its muscular counterpart. And as individuals continue to age, their connective tissue becomes less elastic, less oxygenated, and “stiffer.”6 For years (decades,) the field of sports performance has placed a heavy emphasis on building up the cardiovascular, nervous, and muscular systems, but buried in-between, around, and intertwined through it all is an undefined “myofascial system.” In true Dunning-Kruger form, we’ve had no clue on the impact fascia plays on kinetics and kinematics, nor its delayed timeline, and therefore did not THINK it played a major part—until now.

How Does Fascia Do That?

In 2009, Brisbane, Australia opened one of the most unique bridges ever built, the Kurilpa Bridge. 470 meters long, this bridge uses a combination of steel masts and cables to create tension across the entire structure, making it stable. The amazing part of this sturdy bridge is that it only weighs 560 tons, whereas the Hohenzollern steel bridge, which crosses the Rhine in Germany and covers 409 meters, weighs an astounding 24,000 tons. If you’re like me, you might wonder: how do these two bridges cover similar distances with a 42 times difference in weight?

The answer? Tensegrity. Which is the same principle that allows humans to manage thousands of pounds of force, throw baseballs 90 miles per hour, and lift 3 times their body weight. But how does it work?

Pressure and tension in the human body is created when inward-pulling by muscles and connective tissue against the skeleton allows for the transfer of forces within (kinetics). Our bones act as posts/masts/struts pushing out against the myofascia, allowing forces to transfer between two anatomical points. If we dive even deeper into the tension system, we see that endomysium surrounds each individual muscle fiber, linking them to create a wave of contractile forces within the entire muscle. Our bones are a constant tension point in the body, while the myofascia acts like an adjustable tensegrity unit.

Our bones are a constant tension point in the body, while the myofascial acts like an adjustable tensegrity unit, says @endunamoo_sc. Share on XTo visualize: imagine a bridge with permanent posts (bone) in the ground, and the road (muscle) is supported by steel cables (fascia) anchored to both, creating a stable and strong structure (force management). When a bridge gets longer (bigger kinetic chain), the amount of force distribution becomes more crucial; and, if load is not shared properly, a peak point could cause stress and failure in that area (ergo the hamstring strain).

If we look at high level athletes that suffer season-ending, non-contact injuries—like a hamstring strain—the most likely reason is that a single point in the myofascial network was unable to manage the forces being enacted against it (kinematics). Therefore, the “bridge” collapsed.

Now, the question remains, what do we do with this knowledge?

Row or Sail Across the World?

If you were tasked with taking a boat across the entire world, would you rather row or sail? Roughly 200 people attempt to sail the entire ocean each year, while there has been only ONE person to ever row across all 3 oceans in a single year (and he rode his bike in-between to avoid the long trip around the countries). The obvious answer is that sailing is the better choice—aside from not getting blisters on your hands, sails are able to capture larger forces to move the boat. We can look at different types of training like rowing and sailing.

Rowing is a slower, less efficient, more taxing way to create motion. That being said, it is also a great way to make more precise maneuvers or create motion in environments without a lot of wind. Metaphorically, rowing is like traditional body-split training or rehab, where the kinetic chain use is low, limiting the number of points affecting each other.

Rowing/Kinetics with Low Kinematics (slower direction and positions)

- Bodybuilding Splits

- Low-Dynamic Weightlifting

- Rehab

- Machine Lifting

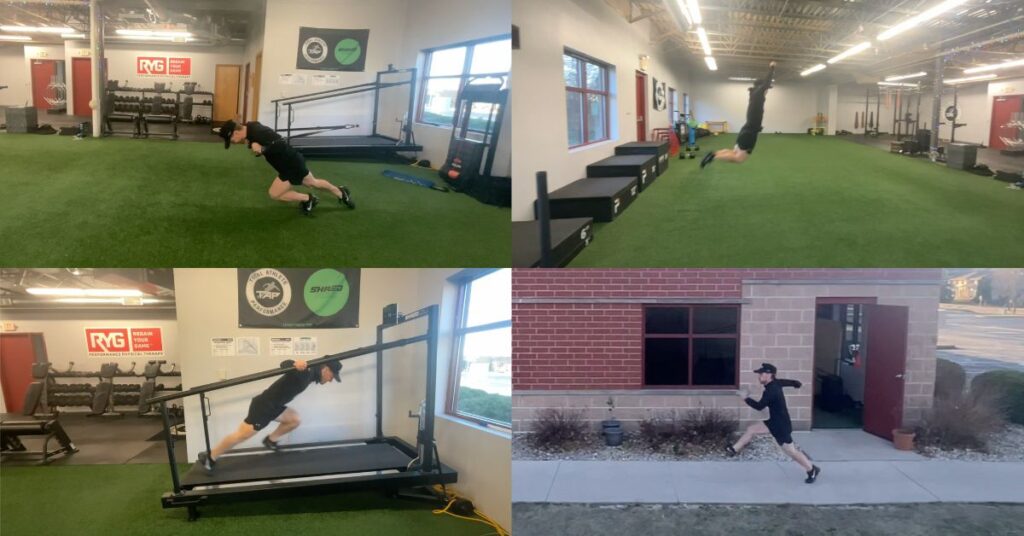

Video 1. Lifts and exercises characterized by low kinematics.

Sailing, on the other hand, will look more like movements that involve the transfer of large forces across multiple structures to create more force management.

Sailing/Kinetics with High Kinematics (higher velocity, acceleration, in positions and direction)

- Sprinting

- Throwing

- Dynamic Weightlifting

- Catching/Decelerating

Video 2. Exercises and activities characterized by high kinematics.

Now here is the secret all those functional-fascial-holistic-mobility-instatok-fitness influencers don’t want you to know – EVERYTHING IS FASCIAL. You cannot contract a muscle without engaging in fascial elements (such as the endomysium). The problem occurs when we either do not prepare the structure in the kinetic chain to withstand the demands we put on it, or we create movements that have high stress points in weaker areas.

If we want to master the large forces on the body (kinetics), we have to figure out the ideal solution for the associated movement (kinematics). When an athlete performs an isolated leg extension, the forces on the body will specifically affect only a few structures. Meanwhile, performing a javelin throw will require force to be transferred and amplified from the toe to the finger. The world’s best body builder is specialized to out-leg-extend the javelin thrower. That means an athlete could perform specific leg extensions to strengthen the VMO; however, if they neglect more dynamic movements in the same area, they have created a “weak” link in the chain.

If we want to master the large forces on the body (kinetics), we have to figure out the ideal solution for the associated movement (kinematics), says @endunamoo_sc. Share on XWhen most trainers use the word “fascial,” I think they mean multi-limb or large-chain exercises. Many of the ones we see online involve a meticulous, multi-step movement that is in stark contrast to a simple machine or bodybuilding style exercise. But creating large chain movements is only half the battle. We know that fascial elements can take more than 4 times as long to adapt as their muscular counterparts, meaning we should not neglect the higher kinematic (displacement, velocity, and acceleration) training styles. This means that not only are large chain exercises important, performing them at speeds and loads that mimic the demands of the game are too. And, unfortunately, neglecting this fact is most likely what happens to high level athletes as they age.

After a grueling season, many take a small break from working out (understandable), but their return to training may have gaps they do not realize. For many, they might simply get in the weight room and lift without much time spent on higher velocity/load styles of training. Others might only spend time doing sprints and cuts, neglecting their own internal weak points that can’t be specifically targeted on the field. Once the season kicks off, and the stress returns, it’s only a matter of time until—BAM—season’s prematurely over.

Is There a Blueprint for a Tensegrity Bridge?

Before a single pile of concrete is poured, engineers must meticulously draw out blueprints that give guidance for creating a sturdy structure. As strength coaches, we do something similar when we create our micro, macro, and mesocycle plans for teams and programs. A major difference is that we do not submit our plans to a committee that double-checks our work to make sure we have everything we need.

Like a city planner checking local code before a blueprint can be approved, we need to understand the expectations of each athlete’s sport, says @endunamoo_sc. Share on XTypically, WE must audit our own training plans and make sure we are filling all the essential buckets—and not only for performance, but also for durability. Like a city planner checking local code before a blueprint can be approved, we need to understand the expectations of each athlete’s sport. Here are the five pillars that a program should consider when “building” an athlete.

1. Load

The greatest load an athlete typically experiences will be during a decelerative moment. Some sports, like soccer, can have over 650 decelerations during a game, with over 70 of them being high g-force (6-8G).7 These large forces, occurring hundreds of times per game, mean we need a high capacity of force management in soccer players. We can achieve this either in the weight room with different-intensites of training, eccentric overload, or other traditional modalities.

Combat sports like football, however, have decelerations that can be as high as 40Gs.8 Although neither of these loads will be touched in the weight room, improving neurological stiffness and joint control is a great way to improve load management and strengthen soft tissue for the season. Likewise, these athletes should be performing high-intensity decelerations to match the impact and volume they might see in a game. This can involve sprinting to a hard stop, or simple depth drops from large heights.

Football players should be performing high-intensity decelerations to match the impact and volume they might see in a game. This can involve sprinting to a hard stop, or simple depth drops from large heights. Share on X

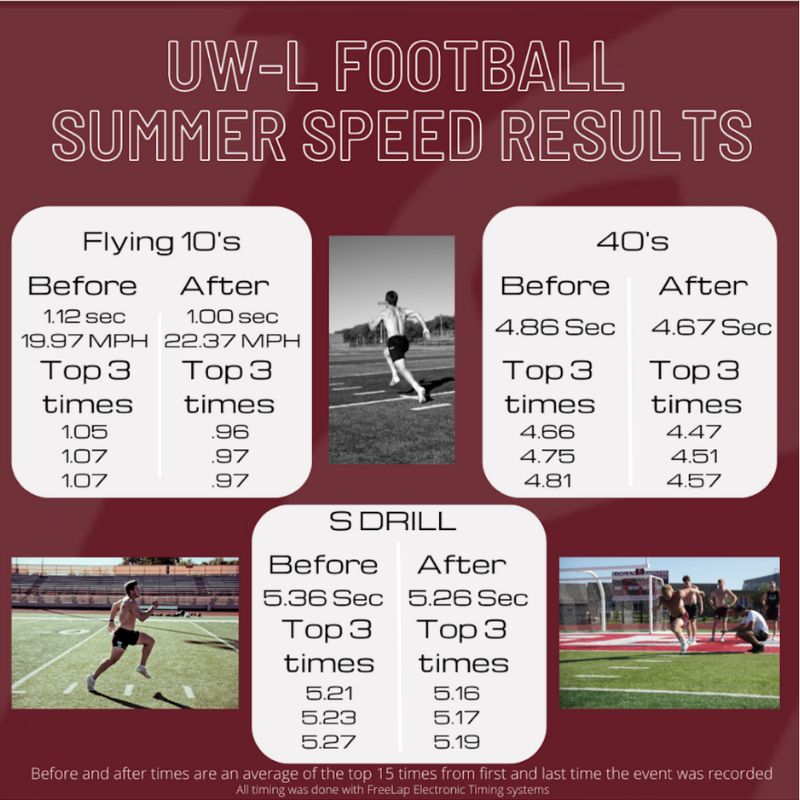

2. Velocity

Sports with a limited arena size, like volleyball or basketball, are not going to have the same velocity demands that a field athlete would experience. Many soccer and football players are clocked sprinting at over 20 mph during breakaways in a game. When dealing with skill players, we need to make sure they are entering into high velocity sprints during their preparatory phases to help adapt their bodies to the high speed/stress they will encounter.

Likewise, athletes that throw and hit can suffer from a caveat of bodily ailments if they do not prepare themselves. Many people only think about the shoulder or elbow—which are very important!—but if any part of the chain becomes inhibited, the kinematics of movement can change and therefore injuries might be more likely. For example, a female volleyball player can spike a ball at 45-60 mph. A common volleyball injury is a back strain, which can inhibit the way a player rotates and thus puts more strain on the arm itself. Like a bridge, when one cable goes, the next is stressed more and then a chain sequence occurs. To mimic certain velocity components, these athletes can perform throws with weighted balls that allow their kinetic chain to mimic velocities up to a point, without year-round stress on their shoulders or elbows.

3. Displacement

Sports involve covering large spaces, at times quickly and at times slowly. They also involve the body maintaining a position while “stretching” itself to cover more ground or more degrees of motion. If the only time an athlete enters a space—kinematically or literally—is during a game, the likelihood of catastrophe increases. Not only are the impacts of these movements felt by the structures, but the quality of these movements can be inhibited if the athlete is uncoordinated and unfamiliar.

If the only time an athlete enters a space—kinematically or literally—is during a game, the likelihood of catastrophe increases, says @endunamoo_sc. Share on XBasketball players jump maximally 40-50 times per game, and these are predominantly vertical in nature—but what happens when they are not?9 These athletes could benefit from performing horizontal jump variations that still build power, but also improve the variable stressors on tissues and coordination. Likewise, many basketball players jump, defend, and run from a higher standing position than other sports—but what happens when they get low to make a play? Incorporating larger ROM training that strengthens them in unique but realistic positions is also important.

4. Acceleration

American football players perform around 35-40 high intensity accelerations over 3.5ms per game. 10 Depending on their position, volleyball players can perform 45-90 jumps (accelerations) per game. 11 Training for both the volume and intensity demands of the many accelerations athletes execute should be at the top of the list for a strength & conditioning coach.

We can mimic some of these qualities in the weight room with velocity-based training, but you will not see a barbell move at 3.5ms—you’d be pressed to get 1.5ms. We can also include plyometrics like standing jumps, but these are typically less than 3ms as well. To achieve some of the acceleration demands athletes have, we also want to perform running jumps, which can reach over 9ms, and short, maximal effort sprints.12

5. Large Chain

In my opinion, these are the movements most people think about when they hear the term fascial training. A quick TikTok search shows hundreds of videos, ranging from stretching to calisthenics to sumo-stance-heel-elevated-deep-goblet-squats. Regardless of each video’s differences, they all share the common trend of elaborate, large-chain movements. This is because a major principle of tensegrity is it requires a NETWORK of compression and tension to be efficient. The more simple and small chain the exercise—a leg extension, for example—the fewer components are brought in, and therefore the less “fascial” it is.

In my program, we have some movements that we describe as “toes to fingertips.” These can be done slow, high load, low load, and fast, but we aim to do them most training sessions. Many yoga stretches that require a large reach are considered slow. An example of a high-load movement would be a close-grip, overhead squat (if you haven’t tried these, I would highly recommend it). For low-load movements, we implement large kettlebell swings or medicine ball slams. Finally, for fast, this can include everything from sprinting to throwing medballs to throwing baseballs to sprinting while throwing medballs and baseballs—or whatever complex movement you can think of.

Bridging Tensegrity and Fascia

If today was the first time you heard the word tensegrity—but the millionth time you head the word fascia—that’s okay. Both terms relate to the same concept, that humans are complex and resilient when we train them right. No engineer, regardless of how smart they thought they were, built the world’s best bridge on their first draft.

With years of knowledge comes an understanding that things are complicated and we must continue to pursue the best way to get the job done. People will still perform sub-par offseason programs, and million-dollar athletes will have season ending injuries that could be mitigated with a better plan. It’s our jobs to show them the blueprints and start building.

References

1. Delos D, Maak TG, Rodeo SA. Muscle injuries in athletes: enhancing recovery through scientific understanding and novel therapies. Sports Health. 2013 Jul;5(4):346-52. doi: 10.1177/1941738113480934. PMID: 24459552; PMCID: PMC3899907

2. Okoroha KR, Conte S, Makhni EC, Lizzio VA, Camp CL, Li B, Ahmad CS. Hamstring Injury Trends in Major and Minor League Baseball: Epidemiological Findings From the Major League Baseball Health and Injury Tracking System. Orthop J Sports Med. 2019 Jul 30;7(7):2325967119861064. doi: 10.1177/2325967119861064. PMID: 31431899; PMCID: PMC6685122.) (Hui Liu, William E. Garrett, Claude T. Moorman, Bing Yu, Injury rate, mechanism, and risk factors of hamstring strain injuries in sports: A review of the literature, Journal of Sport and Health Science, Volume 1, Issue 2, 2012, Pages 92-101, ISSN 2095-2546

3. Boniello MR, Schwingler PM, Bonner JM, Robinson SP, Cotter A, Bonner KF. Impact of Hamstring Graft Diameter on Tendon Strength: A Biomechanical Study. Arthroscopy. 2015 Jun;31(6):1084-90. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2014.12.023. Epub 2015 Feb 19. PMID: 25703286.

4. Bontemps B, Gruet M, Louis J, Owens DJ, Miríc S, Erskine RM, Vercruyssen F. The time course of different neuromuscular adaptations to short-term downhill running training and their specific relationships with strength gains. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2022 Apr;122(4):1071-1084. doi: 10.1007/s00421-022-04898-3. Epub 2022 Feb 18. PMID: 35182181; PMCID: PMC8927009.

5. Brumitt J, Cuddeford T. CURRENT CONCEPTS OF MUSCLE AND TENDON ADAPTATION TO STRENGTH AND CONDITIONING. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2015 Nov;10(6):748-59. PMID: 26618057; PMCID: PMC4637912.

6. MedlinePlus [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US); (updated Jun 24; cited 2020 Jul 1).

7. Maximum Acceleration And Deceleration’s Significance for an Athletes’ Physical Development.

8. Ellen Kuwana. Neuroscience for Kids. Long-term effects of concussions in football players. May 18, 2004.

9. Pliauga V, Kamandulis S, Dargevičiūtė G, Jaszczanin J, Klizienė I, Stanislovaitienė J, Stanislovaitis A. The Effect of a Simulated Basketball Game on Players’ Sprint and Jump Performance, Temperature and Muscle Damage. J Hum Kinet. 2015 Jul 10;46:167-75. doi: 10.1515/hukin-2015-0045. PMID: 26240660; PMCID: PMC4519207.)

10. Delves, R.I.M., Aughey, R.J., Ball, K. et al.The Quantification of Acceleration Events in Elite Team Sport: a Systematic Review. Sports Med – Open7, 45 (2021).

11. Lima RF, Silva AF, Matos S, de Oliveira Castro H, Rebelo A, Clemente FM, Nobari H. Using inertial measurement units for quantifying the most intense jumping movements occurring in professional male volleyball players. Sci Rep. 2023 Apr 10;13(1):5817. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-33056-8. PMID: 37037981; PMCID: PMC10086049.

12. Shaw KP, Hsu SY. Horizontal distance and height determining falling pattern. J Forensic Sci. 1998 Jul;43(4):765-71. PMID: 9670497.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF