[mashshare]

When it comes to utilizing the optimal approach to developing agility, it seems the jury is still out. Most coaches would agree that their training protocols for strength, power, speed, and endurance are pretty similar. But agility is different. Agility is fuzzy, confusing, and muddled with ideas that many tend not to consider.

The goal of this article is to review what has commonly been practiced to develop agility and also shed light on some aspects that are less commonly considered. The specific context for this article refers to field- or court-based team sport athletes.

Agility – What Is It?

The first mistake most people make when thinking about agility is that they believe it simply describes how well an athlete changes direction. Thus, the creation of many “agility” drills to “test” agility: i.e., the 20-yard shuttle, the 3-cone drill, the 5-0-5 test, and many more. These tests and drills measure change of direction ability, which is a component of agility performance. However, these tests have a closed environment, meaning the drill is predetermined and the athletes must simply learn the pattern and then perform it as fast as possible to achieve a high grade.

The ability to change direction is just a component of agility performance, not the whole thing. Share on XOne of the most important concepts to understand about agility is that, in the game, an athlete will not change direction unless something tells the athlete to do so. An athlete must perceive a particular stimulus and then formulate a response to it. As Ian Jeffreys points out in the beginning of his book Gamespeed:

“There will always be a context-specificity to the task, with the athlete moving with control and precision with the ultimate aim of successfully carrying out the task at hand. Importantly, this is not purely reactive, as the athlete will be constantly adjusting and manipulating his movements in relation to the way the environment is evolving around him.”1

Consider an American football wide receiver who catches a football, turns around, and finds no defenders in front of him. He realizes that the end zone is a straight shot and there is an open lane to get there. Will he change direction? No, he will simply sprint linearly at an appropriate speed to reach the end zone and score. Now let’s say that he turns around and there are two defensive backs waiting to tackle him. Will he change direction? Most certainly, as he now sees a set of obstacles that he must maneuver around to reach the end zone. Different contexts, different movement solutions.

One of my favorite definitions of agility comes from Sophia Nimphius of Edith Cowan University:2

“Agility is the perception-cognitive ability to react to a stimulus (i.e., defender or bounce of a ball) in addition to the physical ability to change direction in response to this stimulus.”

We see by this definition that agility becomes about far more than JUST change of direction ability—we have to consider the perceptual (what the athlete reads) and cognitive (what the athlete knows) elements of sensing stimuli in the playing environment and formulating an appropriate movement solution to solve the specific motor problem. A motor problem can be understood as a situation the athlete faces while trying to carry out a sport task. Also, from Nimphius’ definition, we see that it’s not enough to properly perceive the stimuli—athletes must also possess the physical ability to actually carry out their chosen movement solution.

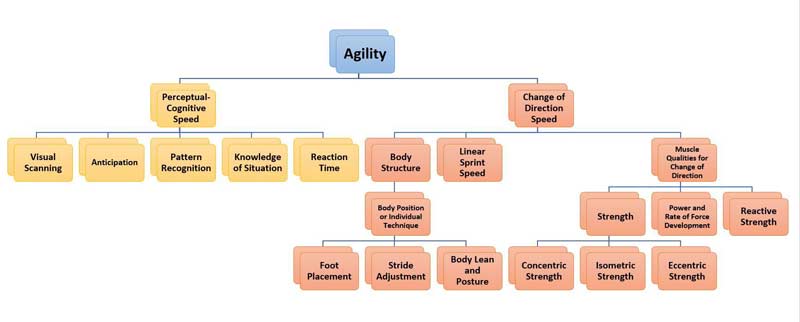

To visualize how broad agility performance is, here is a rendition of a chart from Nimphius:

We can immediately see that perceptual-cognitive speed is one of the two primary pillars of agility performance. Yet, far too often, coaches will ignore this pillar and focus primarily on everything that falls under change of direction speed: namely strength, power, reactive strength, and linear sprint speed. These qualities are absolutely necessary, but we will soon explore the potential implications of ignoring the perceptual-cognitive qualities in the training process.

The Skilled Athlete

One of the most eye-opening books I have read over the past year is Nonlinear Pedagogy in Skill Acquisition: An Introduction by Jia Yi Chow, Keith Davids, Chris Button, and Ian Renshaw. In this text, the authors provide some key points that they feel describe skilled athletes in sport.3

Skilled athletes are able to:

- Produce functional, efficient, and effective movement patterns that appear smooth and effortless.

- Coordinate their actions successfully, with respect to important environmental surfaces, objects, and other individuals, demonstrating precise timing between movements.

- Consistently reproduce stable and functional coordination solutions under the stress of competition.

- Organize movement patterns that are not automated in the sense of being identical from one performance trial to the next, but that are subtly varied and precisely adapted to immediate changes in the environment.

The first point seems obvious. We intuitively understand that the best athletes in the world make their job look easy. But the other three points warrant some consideration. Athletes must understand WHEN to utilize particular movement patterns. This is based upon the environment: where are your teammates, where are your opponents, where is the ball, etc.

The third point stresses the importance of a reproducible coordination solution, not a coordination pattern. This is an important distinction, as it implies that a successful solution (i.e., scoring a goal in soccer) can be accomplished with varying coordination patterns (i.e., bicycle kick, place kick, header). The best athletes appear to find consistent solutions for varying sport problems and do so in flexible, adaptable ways.

The last point explains that movements are never truly identical. We cannot even pick up a glass of water in the exact same way twice. Even when the bulk of the movement pattern seems identical, subtle differences will always exist. These differences are necessary, because they allow athletes to remain responsive to their environment and flexibly shape their movement solutions to fit the specific situation in front of them.

Closed vs. Open/Chaotic Drills

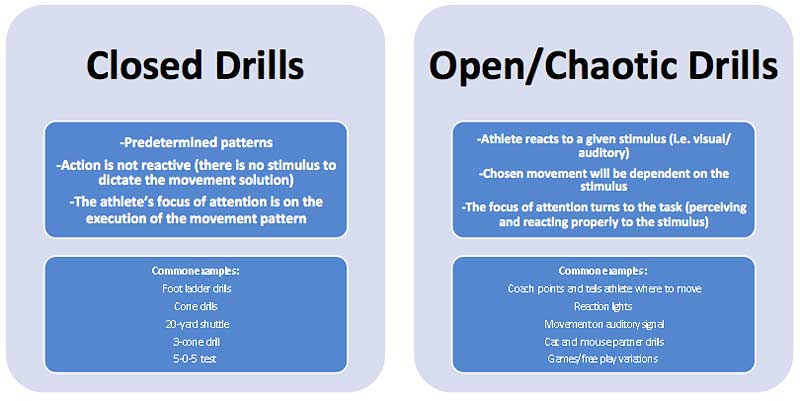

Many progressions seen in agility training programs talk about moving from closed to open drills. We will get into the debate surrounding that progression soon, but first let’s consider what we mean by closed versus open drills. Here are some characteristics and brief examples of each:

Naturally, there will be a continuum between closed and open/chaotic activities based on specificity. Some closed drills have very specific movement outputs that are found in the sport itself, like shooting a basketball without an opponent present. Likewise, some open/chaotic drills can be largely unspecific to the sport, like waiting, reacting, and touching a light on a light board mounted on a wall if you are an NFL linebacker. For this reason, it’s also important for us to understand context.

Context Is Always King

As we can probably guess, it’s not enough just to consider activities in terms of closed versus open/chaotic drills. If we think about combining the two main pillars of Nimphius’ agility chart—perceptual-cognitive speed and change of direction speed—we can start to consider activities in sensorimotor terms. Sensorimotor might seem like a big scary word at first, but it’s really pretty simple to comprehend: If we break it down, we understand it as the combination of sensory, that is, what the athlete senses (sees, hears, feels) and motor, how the sensory system will impact movement and vice versa.

We now know the sensory components of movement are a vital part of agility performance and skill. Share on XThe problem with only using a movement output based approach is that it ignores any emphasis on the role of perceptual-cognitive abilities. We now understand that the sensory components of movement are a vital part of agility performance and skill. Sole emphasis on kinematic and kinetic factors (the shape of the movement and the forces involved in the movement, respectively) is incomplete, namely because they disregard the input of movement. What happened just prior to the start of that movement formation and behavior? Why did the athlete perform that movement in that moment?

Let’s step back and think about sensorimotor experience. A weight-training session will undoubtedly be a very different sensorimotor experience than playing the sport. This also holds true for linear sprint training, jump training, and other forms of power training. These are training environments that are closed and controlled, exhibiting far fewer cognitive elements than what the sport presents.

But what about closed change of direction drills like foot ladders or cone drills? These are also massively different from the sensorimotor experience of the sport. Not only might the movements be dissimilar (like common movement combinations on a foot ladder), but there are no tactical elements involved at all—the athletes do not have to focus on anything outside of their own moving body.

In the world of team sports, where one must account for teammates, opponents, playing equipment, playing surface, playing strategy, and a seemingly endless list of stimuli, any closed drill will completely ignore the pillar of perceptual-cognitive enhancement. Just because an athlete can perform efficient change of direction in an isolated drill, there is no guarantee that the same athlete will be able to avoid opponents successfully or decide the most appropriate movement solution at the appropriate time in the game.

But before we completely throw closed drills under the bus, we must remember that some drills devoted to improving perceptual-cognitive speed (like reaction light training or moving in conjunction with a coach pointing) can also be massively different than the sport from a sensorimotor aspect. It’s not enough to just get the athletes reacting to something; it’s important to understand the context of the stimuli.

It’s not enough to have athletes react to something; you must understand the context of the stimuli. Share on XSo, when it comes to enhancing skill acquisition and agility performance, it is always important to understand the sensorimotor context. Certainly, there will be times when we try to improve general physical qualities like tissue strength/integrity, power, or speed. But if our goal is to enhance agility performance directly, we need to be a lot more considerate about how we construct training methods if we expect transfer to occur.

Debating Agility Training Progressions

With all of the factors surrounding agility training, it’s no wonder that there are multiple viewpoints on how best to train for agility. We typically find two opposite sides in this debate:

- Closed-to-Open Progression: Those who feel that movements should be “mastered” first and then put into open/chaotic environments.

- Constraints-Led Approach: Those who feel that movements emerge as a result of self-organization when athletes are exposed to different levels of environmental complexity.

The Closed-to-Open Viewpoint

For those who are truly interested, this viewpoint is heavily rooted in a theory of motor control known as Schema Theory (also known as Generalized Motor Program Theory). The specifics of this theory are far beyond the scope of this article, but I encourage readers to look into it for themselves.

To simplify significantly, the supporters of this viewpoint believe that movements must be practiced in isolation and achieve a high level of efficiency before being put into more chaotic environments. They believe that no movement should ever be performed “incorrectly” or with bad technique. In this theory, the goal is for movement to be ingrained into the brain as an “efficient” motor program that will then be more automatic going forward with continued practice. If the athlete were to perform a skill “improperly” in training, this might run the risk of the “incorrect” movement technique being stored. Perfect practice makes perfect.

As a result, in this theory, the goal of mastering movements in isolation typically occurs through the use of closed activities. This is where the closed-to-open progression comes about. Have athletes master the movements in closed activities first, then gradually expose them to more complex situations over time.

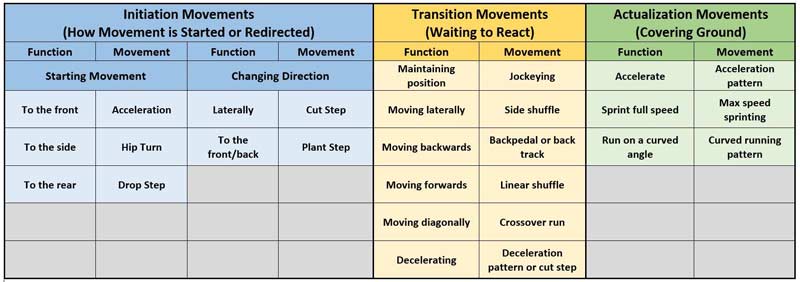

I personally feel that in Gamespeed, Ian Jeffreys does the best job of showing a smooth transition from closed to open drills in a sound, logical progression. Jeffreys classifies three broad categories of team sport movement: initiation movements, transition movements, and actualization movements. Each of these categories contains specific movement patterns, coming together to form what Jeffreys refers to as the target movement syllabus. Figure 3 presents the entire syllabus:1

Jeffreys believes that coaches and athletes should develop these movements individually and with sound technique before moving on to more developmental stages. “Sound technique” here indicates that the athletes understand effective lines of force application, positioning of the center of mass in relation to the base of support, and effective ranges of motion at the body segments and links.

Jeffreys cautions against coaches moving past this stage too early, indicating that if there are any inefficiencies in any of the movements, then developmental stages will suffer and the training effect will not be as large. He believes that we should take ample time to “establish” these basic movement patterns before moving on to more complex situations.

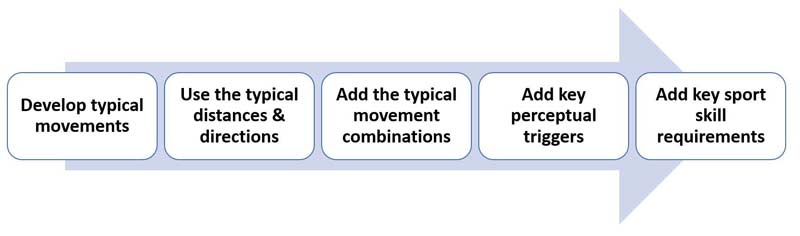

Complexity rises in the Jeffreys progression by moving into a developmental stage that then combines basic movements together. For example, rather than just working a backpedal and a hip turn in isolation, we can now perform a drill where the athlete performs a backpedal into a hip turn. Eventually, in accordance with his model, we can progress to adding perceptual triggers that “add context” to the movements. The progression is outlined below:

So, in Jeffreys’ program, the perceptual-cognitive training elements are added at a later date, in a more-advanced stage of development. Technically efficient movement comes first; exploring the environment comes later. This is a typical progression in a closed-to-open agility training program.

The Constraints-Led Viewpoint

The closed-to-open camp has received some criticism in recent history, primarily from proponents of dynamical systems theory and those that focus on ecological dynamics. Whoa…big scary words again. Let’s break them down to make them simple to understand.

Dynamical systems theory really just refers to the idea that systems are constantly in motion and behave in ways that are hard to predict. It is a field of science that focuses heavily on holistic viewpoints, adaptive self-organization, relationships, patterns, and cycles. Where the proponents of a closed-to-open progression view the training structure as a seemingly linear process (going from controlled, closed drills to open/chaotic drills), the proponents of dynamical systems see skill acquisition as more of a non-linear process. In other words, skill acquisition is very complex, with multiple layers of possibility, where skills might appear and disappear depending on context and circumstance.

Ecological dynamics, specifically the field of ecological psychology, basically stresses that information is a potent stimulus for action. Ecology is the field of biology that focuses on how organisms relate to those around them and their physical environment. Information processing determines outcomes. So, if we consider how this relates to team sports, we can understand that information from the environment, as well as information from within the athlete’s body, will come together to foster the decision-making process of the athlete—not the least of which includes the selection of a movement solution.

A key point within this theory is that information will regulate actions, not enhance automatic responses. Put another way, athletes will learn to interpret patterns of play, make their own decisions, and create movement solutions based upon their perceptions in conjunction with their task responsibilities. Here, we revisit the perception-action cycle: Athletes perceive information, act accordingly, and then their actions bring about new information, so the cycle repeats itself over and over.

In this way, information presented to the athlete becomes a major key in determining the enhancement of agility performance. This is the reason an isolated movement could look exactly the same as a movement in the game and yet be a completely different experience from the vantage point of the athlete. The information presented in a closed drill is simply nothing like the information presented in the game. To push us closer to expecting positive transfer, the movements and the information must both be based upon what is found in the sport.

In this dynamical systems-based approach, one of the leading researchers, Karl Newell, has helped devise a model that explains how information available to the athlete will be based upon a series of constraints—that is, a series of factors that can limit the ability of the athlete to perform. Newell classifies three different forms of constraints: performer constraints, environmental constraints, and task constraints. These are fairly simple to understand and we can summarize them in the following table:1,3,4

These constraints will dictate affordances, a fancy word to describe the athlete’s opportunities for action—what is the environment affording for the athlete to do? These affordances are information sources and are based upon internal and external constraints.

At any given moment, constraints from multiple categories occur simultaneously, which means that the athlete has access to an incredible amount of information from outside and inside the body. It is therefore important to minimize the amount of information to account for the most important pieces for action. This is a developmental process, whereby novices struggle to interpret the right perceptual cues and experts can completely ignore irrelevant information and only focus on what experience has taught them to pay attention to.

Since constraints will dictate the information available to the players, they can also dictate information present during training drills. The constraints-led approach to training basically describes the process of coaches purposely manipulating particular constraints to challenge the perception and coordinative abilities of their athletes.

What might this look like? Well, the easiest constraints to manipulate are task constraints—coaches can change the size of the playing area (i.e., wider and shorter fields or narrower and longer fields), the number of players involved (i.e., 1v1, 2v2, 7v7), or even the decision whether to provide any coaching cues. You can also manipulate physical environmental constraints by having athletes perform drills in the rain or the cold, of course ensuring that nothing ever gets out of hand and/or potentially dangerous. Physical performer constraints can come about organically as developing athletes get bigger, stronger, faster, and more powerful, and must learn to coordinate their new output abilities within the confines of skilled performance.

Therefore, a progression of agility training from the constraints-led viewpoint is one in which you use open/chaotic drills throughout the entire training process, not defined by a particular stage of training. You would base the progression on moving from less complex environments to more complex environments with the task as the primary focus of attention, rather than the movements themselves. The idea is that movements will occur organically, developing alongside the perceptual-cognitive aspects, thus keeping the perception-action cycle intact throughout the process.

Where Is the Athlete’s Focus?

If we accept that focus and attention are performer constraints, then we must consider what the athletes focus on when performing drills in training. As stated previously, closed drills will inevitably force athletes to really think about their body movements, making them self-conscious of their foot placement, hip height, etc. This is exactly why we will see athletes typically looking at the ground during closed change of direction drills—a gaze that would get them badly beaten on the field of play.

In contrast, task-oriented drills where the focus of attention is outside the athlete’s body can allow for the movement selection to occur out of necessity, rather than because they are instructed to do so. For example, if a drill consists of a player trying to avoid an opponent, then he will focus on the opponent and how to get by him, not on where he places his feet. He might use a cut step, a back juke, a spin move, or whatever else, depending on what he perceives. If he gets by the defender, the movement was effective in that moment…if not, then he must learn to explore different affordances on the subsequent repetitions. Some moves might work on some reps and completely fail on others, so the athlete must learn to let his perception guide his movement choice.

Task-oriented drills teach athletes to let their perceptions guide their movement choices. Share on XSome closed activities can allow for external focus of attention as well, like shooting a basketball. The task is to put the ball into the basket. This task can remain the same while the complexity rises. Take a novice and allow him to explore how to put the ball in the basket by himself from various shooting distances. Now add a defender. Whoa, scoring just became that much harder. What about two defenders? What if we give him a teammate to pass to who can also try to score? These are ways to progress in complexity over time where you encourage the athletes to explore their affordances for action and let the task of scoring on offense remain constant with added constraints.

Coaching and Providing Feedback

As we saw from the work of Karl Newell, coaching cues are a form of constraint. If we accept this, then it is a dire point to consider. The feedback that a coach gives an athlete can quite literally make or break performance. How many times have we all seen athletes get overcoached, becoming so self-conscious that they forget how to even play the sport? Overcoaching risks overloading and stressing out the athletes’ brains, leading to rigid, frozen, confused states that demolish any chance of smooth athletic skill.

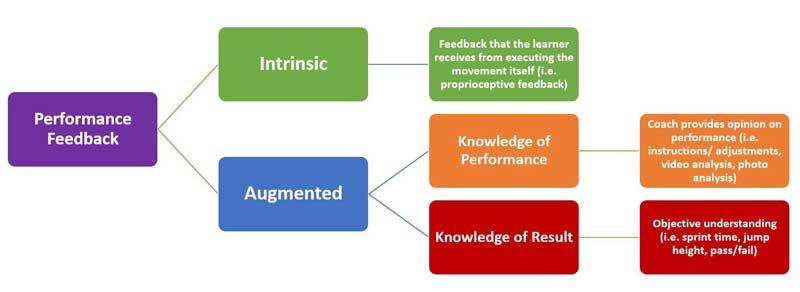

Coaching cues are a form of constraint: Feedback you give an athlete can make or break performance. Share on XThere are different types of feedback that athletes receive while performing skills in training, practice, or games. These feedback categories are provided in Figure 6:4

Intrinsic feedback is when athletes explain that a movement just “felt right.” They understand, through proprioceptive feedback and kinesthetic awareness, that the movement was both efficient and effective. However, this experience can be faulty if you encourage athletes to perform in a way that is actually not effective or efficient. This is where the laws of physics come into play, where attractors, or “biomechanical truths,” are hard to argue.

Attractors are essentially principles of movement (not exact movements) that must occur for motion to be successful. As an example, athletes will quickly discover that if they want to become more stable when changing direction, they must lower their center of mass by sinking into their hips to allow for the proper force application. However, how much they lower their hips will be context dependent—this is what is known as a fluctuation, or how the actual movement execution will be based upon the specific situation.

It’s important for us as coaches to really analyze and determine the difference between a biomechanical issue and a natural fluctuation that might be unique to that athlete. Consider sprinter Michael Johnson, who had very unique running form but still won gold medals, or how basketball star Steph Curry has a unique shot that still proves to be effective. This then begs the question: If the athlete is consistently able to accomplish a sport task in a biomechanically safe way, but looks a little “different” while doing it, can we ever really say it’s “wrong”?

So, we have to be careful when providing knowledge of performance. If we focus on an element that really is not a performance detriment, then we simply waste time. You can use coaching cues, video analysis, or photo analysis to help athletes further understand what you expect of them, but they must never forget the task itself. The more that we can utilize knowledge of result—that is, providing the athletes with objective feedback about the task—the more we can keep the focus of attention away from their bodies and more on the task or environment. In my personal experience, I have seen many athletes find efficient and effective solutions to activities like sprinting or jumping just by simply telling them their time or their jump height.

In the case of open/chaotic agility drills, as long as the task is clearly defined, then the knowledge of result becomes a pass/fail experience. The task was either accomplished or it wasn’t. Did the quarterback complete the pass? Did the point guard get around the defenders for the layup? In this way, coaches can attempt to identify why tasks are not being completed successfully or continue to let the successful athletes explore their opportunities with carefully applied augmented feedback.

In the grand scheme of things, most coaches would agree that we need a combination of knowledge of performance and knowledge of result for the most appropriate player-to-coach experience. The ratios between them are based upon the coach’s judgment and the player’s individual performer constraints.

Examples of Open/Chaotic Drills for American Football

Below are some brief examples of some open/chaotic drills that coaches can use for American football. Most of the clips feature activities that I have used with my athletes. My good friend Scott Salwasser, Director of Speed and Power at Texas Tech University Football, also shared some clips of drills they have used with flag belts and reaction belts. They used the drills in large group settings (100+ players working out together), and he has found that the belts help keep players engaged in the task and make it easy to determine pass/fail. Scott is the only Division I football performance coach that I personally know utilizing a systematic approach to the open/chaotic activities.

These are just SOME examples to help illustrate how creative these activities can become. If the coach uses the sport as a guide, focusing on movements AND perceptual-cognitive factors, then the limit of drill design is at the mercy of the coach’s creativity. Easy factors that you can manipulate include: size of the field space (i.e., wider vs. longer fields), number of players involved in the activities, and rest time in between repetitions of effort.

Also take notice of the movements that naturally occur in these drills, all of which make up Ian Jeffreys’ movement syllabus: acceleration, curved running, hip turn, drop step, cut step, plant step, shuffle, backpedal, back track, crossover run, jockeying, and deceleration.

Lower Complexity Drills

Open Field Tag 1v1

In this specific variation, I use a boundary of 20 yards’ depth and a width between the hash marks on a high school field. The players can line up anywhere they want to in this boundary and I encourage them to change their alignment depth or width on every repetition. The pursuing player must be in a position where he can face the “it” player. The player that is “it” will start the drill on his first movement, at which point the pursuing player must track him and attempt to tag him with both hands before he reaches the end zone. I give a point to the player who “wins” the repetition.

Video 1. Open Field Tag 1v1 Drill

1v1 Tag Variations with Flag Belt – Scott Salwasser, Texas Tech Football

Just like the previous drill, the field space can be variable and the angles of pursuit can change. Here the goal becomes about keying the eyes on the hip of the “it” player, pursuing at an appropriate angle, and trying to remove his flag. The challenge for the “it” player is to prevent his flag from being pulled. You can scale complexity in favor of the “it” player by using flags that have been cut shorter, making it more difficult for the pursuing player to grab the belt.

Video 2. 1v1 Tag Variations with Flag Belt Drill

1v1 Coverage Variations with Evasion Belt – Scott Salwasser, Texas Tech Football

Where the tag variations require the pursuer to meet the “it” player at the point of attack, these coverage variations now require the pursuer to maintain leverage with the “it” player. The evasion belt is attached via Velcro straps and serves as a feedback response to the players to understand separation between them. The goal for the “it” player is to make maneuvers and try to sever the belt, while the pursuing player must do all that he can to keep the belt intact. If the belt breaks, the “it” player achieved sufficient separation. If not, the pursuing player did a good job of staying with him.

Video 3. 1v1 Coverage Variations with Evasion Belt Drill

Higher Complexity Drills

Pass Coverage 1v1

For football players that must engage in one-on-one man coverage situations, this drill is as foundational as it gets to learning how to manipulate the man across from you. The receiving player knows where he should go, but must find a way to get there by maneuvering around the covering player. The covering player does not preemptively know where the receiving player is heading, but must stay disciplined to reading his hips and finding proper leverage to stay with him and prevent him from catching the football. This drill proves more physically challenging for the receiving player and more perceptual-cognitively challenging for the covering player, but both players must deal with aspects from both sides.

Video 4. Pass Coverage 1v1 Drill

Pass Coverage 2v2

This drill is essentially the same concept as the pass coverage 1v1 drill, but now there are the additional teammate and opponent to consider in the environment. Spacing becomes important and the players do not know who will get the ball, so task completion is necessary on every repetition.

Video 5. Pass Coverage 2v2 Drill

Running Back vs. Linebacker Run Play with Blocker and Audible Cue

This was a more-contextual drill design that I put together to simulate aspects of the run game between running back and linebacker. The blocker and the running back decide on a run play together before lining up. The blocker can line up as either an offensive lineman or a fullback. The running back provided the cadence (i.e., “Set…GO!”), after which the play is initiated. After the start of the play, the blocker calls out a particular direction (left, middle, right), which indicates the cone that the running back must try to reach behind the linebacker. So, the running back must initially follow the play, locate the linebacker, and then attempt to avoid him while also trying to reach the designated cone behind him. For the linebacker, he must make a run read, avoid the interference of the blocker, and attempt to tag the running back.

Video 6. Running Back vs. Linebacker Run Play with Blocker and Audible Cue

My Current Template

Here is a basic overview of my high school and college football template, including where I place my focus on agility drills/games:

| Mon | Tues | Thurs | Fri |

| Short Acceleration

1. Sprint Variation 2. Agility Drills/Games 3. Vertical Jumps 4. Explosive Lifting 5. Upper Body Max Strength |

Long Acceleration

1. Sprint Drill 2. Sprint Variation 3. Explosive Power Drill 4. Vertical Jumps 5. Lower Body Max Strength |

Short Acceleration

1. Sprint Variation 2. Agility Drills/Games 3. Vertical Jumps 4. Explosive Lifting 5. Upper Body Power and/or Hypertrophy |

Speed

1. Sprint Drill 2. Sprint Variation 3. Elastic Power Drill 4. Vertical Jumps 5. Lower Body Max Strength |

Figure 7. My current high school and college football weekly template. Note: The agility drills/games have a large aerobic component that simulates what is found in the game. There are times when I will add additional general aerobic work if time permits.

So, What’s the Answer?

After all of this, are closed change of direction drills useful for developing agility? The answer always rings the same: It depends.

This is the part of the article where I supply my personal opinion, but still encourage you to determine your own. I believe that closed change of direction drills DO have a place in the training process, but I believe we should use them as minimally as possible. In fact, the greatest place I see for them is in the rehabilitation process or when very specific tissue loading is the primary objective. However, closed drills in the form of resistance training, linear sprinting, plyometrics, and other forms of power training can easily coexist among agility-based drills and games.

I believe closed change of direction drills have a place in the training process, but a minimal one. Share on XIt was once a suggestion that athletes should not participate in plyometrics or sprint training until they have a solid “foundation” of strength. Way back when it was also said that athletes need to build an aerobic base before moving into strength training. Most strength and conditioning coaches would now scoff at these ideas, knowing that they are completely outdated and serve little merit. And yet, the mindset of agility training is currently in a similar vein as these older ideas.

The argument against the strength base for plyometrics and sprinting was thwarted by the simple idea that very young kids show the ability to perform sprinting and plyometrics without ever participating in organized strength training. The same holds true of agility: kids are constantly running around and playing, perceiving their environment, falling and getting back up, and developing their body awareness and awareness of everything around them. Even just chasing the family dog around helps to develop agility-based qualities from a perception-action standpoint.

I believe that when it comes to training aimed at developing agility, we can achieve a lot by starting on the open/chaotic side of things and peel back from there when necessary. We can change constraints based upon where a particular athlete is in their development.

To develop agility, we can start with open/chaotic drills and peel back from there as necessary. Share on XAs an example, let’s say we have a basic tag-based game. The athletes that are more skilled in their ability to pursue the “it” player can be aligned further away from them, the greater distance being more of a challenge to close down space and successfully tag the player who is “it.” In contrast, a less-skilled tagger could be aligned closer to the “it” player, making the task a little easier in terms of closing space. From there, we can slowly start moving the less-skilled player around to different positions, making them more comfortable being uncomfortable.

But to be fair, sometimes the athletes will simply not understand a movement principle (attractor); whereby, if they did, their performance would improve. This is where augmented feedback in the form of knowledge of performance is valuable. As a coach, I could step in and pull that athlete aside and run them through a quick closed change of direction activity to allow them to feel the attractor. While the majority of the time we might want to give athletes an external focus of attention, we cannot ignore that sometimes an internal focus of attention is necessary to allow an individual’s brain to comprehend a biomechanical principle. Everyone is different in the path they take to learn skills.

Ultimately, if we throw an athlete into an open/chaotic drill and they show the ability to adapt, adjust, and self-organize, repeatedly finding task solutions without us having to say a word to them, that’s an immediate victory. By doing this, we as coaches can find the less-skilled athletes who struggle in agility-based tasks and then determine what the limiting factor of their performance might be.

Some athletes simply struggle with perception, unsure of what they are looking for. We can help them here. Other athletes know exactly what to look for but are seemingly unable to get into an appropriate position to act accordingly. We can also help them here. It’s on us as coaches to determine where the true performance inhibitors are and get creative in determining how to remove them.

My wife (who does not study anything agility-related) was able to explain it to me concisely. When teaching someone how to drive a vehicle, at some point we just need to let them take the wheel and drive. During the learning process, we might be able to provide some hints (i.e., here comes a stop sign, help signal to the others that you’re going to turn, check your blind spot before merging), but we can’t hold the wheel for them or always be in the vehicle with them.

The same goes for team sport athletes. We have to find ways to let them drive their own vehicles, exploring their own bodies and their surroundings. We can be guides and teachers, but should avoid being dictators and micromanagers. When the game kicks off, we can’t be in the vehicle with them anymore. It’s on us to come together and determine the most efficient path to helping athletes take the wheel and drive.

References

- Jeffreys, I. Gamespeed. 2nd ed. Monterey (CA): Coaches Choice; 2017.

- Nimphius, S. Increasing Agility. In: Joyce D, Lewindon D, editors. High-Performance Training for Sports. Champaign (IL): Human Kinetics; 2014. p. 185-187.

- Chow, J., Davids, K., Button, C. & Renshaw I. Nonlinear Pedagogy in Skill Acquisition: An Introduction. New York (NY): Routledge; 2016.

- Bosch, F. Strength Training and Coordination: An Integrative Approach. Rotterdam (NL): 2010Publishers; 2015.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

[mashshare]