[mashshare]

Disclaimer: I love the squat and I love deep squats. I come from a powerlifting background and feel a deep sense of pride that I would miss squats rather than cut them high. This was my sport, and I took great pride in my sport. Some say that I hate deep squats, but that isn’t it at all.

I just happen to think that things that are great for one sport aren’t great for all. I’ve gone on record many times as saying that we don’t need perfect technique on Olympic lifts. Reasonable is good enough and, in fact, I mostly just did pulls with my athletes. Likewise, do we need to have a powerlifting standard for squats? Food for thought as we go ahead. Many will disagree, and that’s OK, but I feel that we need to get this information out there now rather than later.

Introduction

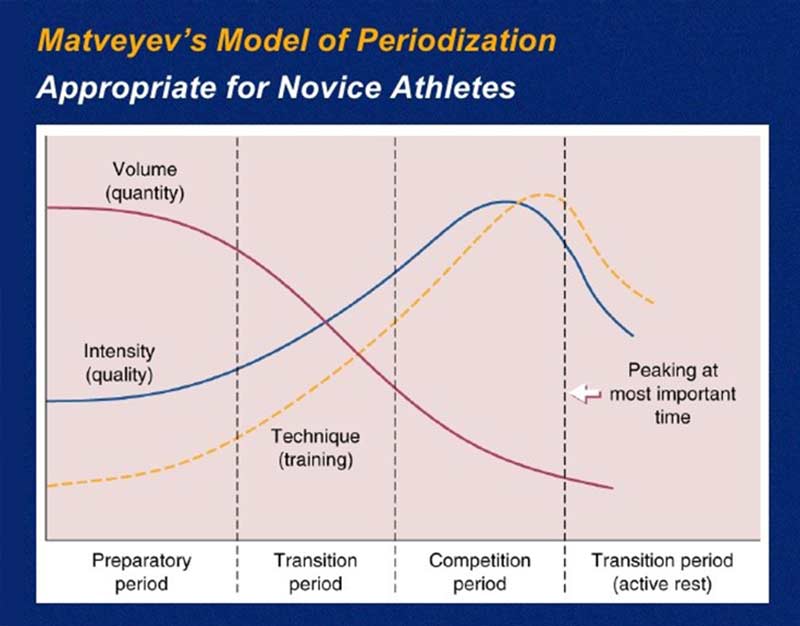

If we remember back to the classical periodization models, we see that they were listed out in very general terms. There was Volume, Intensity, and Technique, and that was all. When looking at the Volume and Intensity lines, I think that current strength and conditioning practices are fantastic. Most coaches start with a higher volume and lower intensity (percentage of 1RM) in the off-season; during the pre-season, they decrease volume and increase intensity (percentage of 1RM); and then during the competitive season, they keep both volume and intensity (percentage of 1RM) to maintenance of gained levels.

However, I think there are some areas that we can improve or we have possibly misinterpreted. It is not uncommon for something to be lost in translation. For instance, we have colloquialisms in our language, and they don’t translate into other languages very well, as I found out in China. We had our nomenclature and applied the Soviet nomenclature to it. The Soviet literature had two phases: GPP and SPP. Intensity, from talking to others who speak and translate from the Russian language to English, was more about the quality of the movements and how specific they were. While percent of 1RM absolutely plays a part in it, it’s less important than the exercise.

Was technique referring to sport skill only, or did it also relate to transfer of training for the weight room? For example, in some of Vherkoshansky’s work1, he changed from squat to squat jump or some other exercise, and didn’t maintain the squat from block to block. He went from a general exercise to what he felt was a more specific exercise for his athletes. They progressed their types of jumps from extensive long coupling to intensive short coupling over time. They didn’t just change the type of movement, but changed the movements themselves. For instance, they went from steadier, coordinated bodyweight squat and tuck jumps to drop jumps and bounds over the course of the training cycle.

History Lesson: How to Apply the Work of Matveyev and Bondarchuk

Before continuing, I think it wise to note that at no point are any of the three variables ever at zero in Matveyev’s chart2. What this indicates, at least to me, is that there is a small portion of everything in at all times, but the emphasis is switched. This was confirmed to me by Doc Yessis and Anatoliy Bondarchuk about the typical Soviet programming, and the proportion they gave was that there is typically an 80/20 split during the GPP phase of 80% general exercises and 20% specific exercises. This made a gradual shift to the SPP phase, which ended up being 80% specific exercises and 20% general exercises.

One area that we could do better on is the alternation of exercises through the course of the year to elicit greater gains. A recent study by Rhea et al.3 showed that the ¼ and ½ squats had better transference to the sprints and jumps than the full squat. There are two groups that read this article: The first group has cut out full squatting altogether and only does ¼ and ½ squats to have greater transfer; and the other group calls it heresy, wants Matt Rhea, Joe Kenn, and the other authors all burned at the stake, and refuses to think for a second that the almighty ass-to-grass squat may not be the best thing.

How the Standard of Squatting Was Determined

An interesting side note, and a question no one ever seems to ask, is: How did the crease of the hip below the knee/top of thigh become the standard of squatting? I have unique access to information such as this, as I often lift in Bill Clark’s gym. Bill Clark is the last remaining member of the three-person committee that started “powerlifting” as an offshoot of Olympic lifting, and I talk about this in a section with him in my book, “Powerlifting”4. I asked him this question and I’m paraphrasing his answer. (If you’ve ever spoken with Bill, a two-second question can garner a two-hour answer.) “Well, we needed to have criteria for what made a good lift. For deadlift, it was easy. You stand up with it. For bench press, it was easier than the squat. You go down, touch your chest, and come back up. For the squat, it was a bit more abstract so we chose what seemed to make the most sense—the crease of the hip and the knee. If you went below that, it was a good squat because you went low enough. If you didn’t, it wasn’t.”

Ole Clark, as he is affectionately known around here in mid-Missouri, is a stickler for squat depth, as well he should be. However, has our love affair with squat depth as the crease of the hip below the knee, which came about as a compromise between three people for a rule, become the reason for the ass-to-grass squat? I’m not completely sure, but I started in S&C from a powerlifting background, and I know many of us in S&C have. This is where my viewpoint on the squat came into play, and I made everyone squat to depth because that was the standard.

My Evolution in Strength and Power Training

Before moving forward, I want to point out my own fallacy. My athletic background is as a powerlifter. I still am addicted to strength and heavy loads even though my body is broken down. So please don’t take this as a “he’s an anti-strength guy and all single joint specificity guy blah blah blah, yada yada yada…” Take this as a “been there, done that, bought the T-shirt,” guy who is trying to help others learn from his mistakes.

When I started out in this field, I looked at everything from the viewpoint of the squat, bench press, and deadlift. Admittedly, I tend to track back to that every now and then (full squat and deadlift 1RM), but I looked for ways to make the squat more effective for longer term periods, and really expanded into velocity-based training from that. We would squat for strength and for strength-speed. When that was done, we saw greater power and speed gains over the longer time period of the course of their career, but there was a limit.

Managing Complex Training Variables

Where Jacobson et al.5, and Miller et al.6, found the gains of squat transfer-to-power extend for one year, we had them extend for three years7, with the second and third not being anywhere near as steep as the first. This may be partially explained by the use of velocity on the squat and the use of accommodating resistance (chain, in our case) during training8. The gains did stop, though, before the fourth year, and on average we did not see any improvements at all. What would have happened if we would have periodized the exercises, rather than the velocity/intensity? I’m not sure. Would moving away from the squat for a while have had a beneficial effect on the athlete? Possibly, but I’m not sure. What I do know is that altering the squat from strength had a beneficial effect.

For a moment, let’s go with an open mind and look to apply the findings of Rhea’s study3 to the original Matveyev model. If we remember that the purpose of the GPP phase was to restore and increase general qualities such as general strength, mobility, and work capacity, we see that the full squat absolutely checks those off the list. As we gain in strength, mobility, and work capacity, and hopefully power, as a result of this, we are fulfilling the purpose of GPP, and thus, this is the appropriate time to utilize the squat. If we then think of the SPP phase as using specific exercises, we can utilize the ¼ and ½ squats most appropriately at this time. The study showed that trained athletes had the greatest transfer to the sprints and jumps, which fulfills the requirements for SPP.

Now, some people may question about the transfer of the ¼ and ½ squat to the jumps and sprints, and that’s fine. Let’s look at some pictures of an elite level sprinter and go into more detail.

If we examine Image 2, let’s look specifically at his drive leg right now. Some folks on Twitter looked at an image similar to this one and said, “See how high his leg is? That looks like a full squat to me.” While I will agree on the hip and knee flexion angles being representative to the squat, how did he get there? Did he get there by lowering his center of mass until he got to this position? No. He went through a violently rapid hip flexion and drove the knee forward to get into that position. Try doing that on a squat—let’s see what happens if you drive one or both knees to your chest and in front of you from the beginning of a squat.

My point is that, if the squat is done in this manner, the individual will either a) dump the bar or b) land on his tailbone. It’s not simply the picture of what someone achieves, but how the person got there is extremely important as well. The hip extensors working eccentrically or the hip flexors working concentrically to achieve hip flexion are two very different activities.

Some will say it’s about the drive from the thigh moving downward to the ground. While there is acceleration downward from the thigh from the hip, it’s unimpeded until the foot makes contact with the ground. At the point when the foot meets external resistance (the ground), the squat strength takes over. Before the increased force production due to ground contact, the majority of force production comes from the sarcoplasmic reticulum. The sarcoplasmic reticulum’s release and re-absorption of calcium enables the actin to be released for the myosin to grab a hold and pull the actin towards it. This allows for the rapid contraction utilizing the sliding filament theory of muscle contraction.

If we examine Image 3, we’re in the stance phase on the right leg, with the left leg going into the drive phase during the accelerative portion of the sprint. As a side note, Dr. Michael Yessis would tell you this is an example of great technique9. If at this point in the sprint you see two calves and one thigh, they’re doing it right. If we examine the right leg during this phase, we can see that the right leg is slightly bent during this portion of the sprint. This is going to be one of the deepest portions of the sprint outside of coming out of the blocks that the knee will bend. How low is his squat? I’d say it’s probably around a ¼ squat. During the sprint, there is no full squat.

Breaking Barriers in Exercise or Training Bias

I think that we have allowed ourselves—myself included—to become married to certain exercises; to say that this exercise is the foundation of our program and we should never move away from that. This reminds me of the railroad industry. They have since fallen on hard times, but at one point in our great country, they were the king. They felt that their job was to put railroad tracks down and put trains on them, and move people and products across the country. When the automobile came along, it made the railroad obsolete because people could go anywhere they wanted on the highway system and were not constrained to their routes and locations. The railroad then fell to a point that, while it is still a great industry, the giants of yesteryear no longer exist.

If we stop favoring certain individual exercises, we may improve the results we get with athletes. Share on XIf we say our job is the squat, the hang power clean, and the bench press, and that is what we will do come hell or high water, is that the best thing for our athletes? If it has worked for decades for building athletes (one to two years at a time), it should be in. Well, it hasn’t worked. When it has been done in Division 1 athletes5,6, the research is clear.

If we re-examine ourselves and cut our ties with individual exercises, we may be able to enhance the results we get with our athletes. If we change our viewpoint on this and look in terms of what is most specific for a certain sport/event/position within a sport, and apply this at the appropriate time, then we can look to cause the greatest transfer. We must remember that in no sport is there a barbell involved, other than powerlifting, strongman, odd lifting, or Olympic lifting. Even for those, odd lifting and strongman often don’t use barbells. Because of this, the training choice should be based on transfer of training rather than the increase in a 1RM. This does require a paradigm shift, but one that I think is quite beneficial. We remember from Zatsiorsky10 that transfer of training can be determined by the following equation:

Transfer of training = Result in event/result in trained exercise

At this point someone will say, “I have a team sport, so that’s not possible. I’m going to continue what I’m doing.” While it’s true that this is more difficult in team sport, we can’t say that the performance in the weight room was related to the sport. There are too many confounding variables. We can’t account for the other team, the interactions between team members, the play calling by the coach or individual on the court, or even the environmental factors like the crowd. We do know that we have certain metrics that are predictive of abilities for sports, which are often called Key Performance Indicators (KPIs). For instance, jumping has been shown to be predictive of excellence in volleyball and basketball. For football, it’s been found that the standing long jump is a great predictor when combined with sprint and agility tests. In these cases, when we look at the result in the KPI and divide that by the result in the trained exercise, we can get a great example of where we stand.

If we look at the work by the great Soviet hammer coach and medalist, Anatoliy Bondarchuk, we see that every time they went through the adaptation process, he changed every single exercise. He did not leave one exercise in because it was his anchor. (In this example, I refer to the GPP, SPP, and SDE means. He would keep the throws in, but even then, it might be competition weight, or slightly heavier or slightly lighter)11. Every cycle was entirely new and stay entirely the same until they went through the adaptation process, and then everything changed again12. He would track and know what exercises had the greatest transfer for the throwing event, and even the athlete. When it was time for a key competition, he would put in the exercises that had the greatest transfer to the event/athlete.

If we re-examine our terminology and look intently at the term “quality,” it may start to help make sense of some things. It allows us to not view things in terms of 1RM, but in terms of how closely it ties into the sport, and how close it transfers. It may not replicate a portion of the sport, but that’s OK. It’s all about the transfer to the sport itself.

So, let’s look at the squat. Once we enter the SPP or pre-season phase, if we alter the back squat to a ¼ squat for a block of training and then a ½ squat for a block of training, we are giving two different stimuli that have a higher transference to the sport. Once we go through those, we may switch back to the ¼ squat and alter it with either an accommodating resistance or a change in bars. We may possibly even change to a lower box step-up for something else that allows the body to re-stabilize and go back through again.

Here is an example of what this may look like:

| Phase | Weeks | Exercise | Intensity (% of 1RM) |

| GPP 1 | Weeks 1-4 | Full Squat | 60-70% |

| GPP2 | Weeks 5-8 | Full Squat | 70-80% |

| GPP 3 | Weeks 9-12 | Full Squat | 80-90% |

| SPP 1 | Weeks 13-16 | 1/2 Squat | 60-70% |

| SPP 2 | Weeks 17-20 | 1/4 Squat | 70-80% |

| SPP 3 | Weeks 21-24 | Low box step up | 60-70% |

| SPP 4 | Weeks 25-28 | 1/2 Squat variation (accommodating resistance or bar change) | 60-70% |

| SPP 5 | Weeks 29-32 | 1/4 Squat variation (accommodating resistance or bar change) | 70-80% |

Many people tend to argue against periodization and say that it’s dead. Then they’ll talk about how they alter from more general to more specific exercises over the course of the year as they move into their season. Having a plan and changing to more specific from more general is periodization. What we must remember is that periodization doesn’t mean doing x sets times y reps at z intensity; it is a plan of what will be done and when for a period of time. Interestingly, this means that many of those who argue against periodization are actually arguing against one form of programming. This is great: We all agree that there needs to be planning, but we argue about what the best plan is.

This is only an example of one exercise. Let’s say, for instance, that over the course of the year we find that the mid-thigh power clean has the greatest transference to the sport we happen to be playing. Is that saying that we don’t ever do the other variations? No. Absolutely not. What it says is that, during the SPP phase, the mid-thigh power clean is our go-to, especially for when we are moving in to what may be the championship. There will be many exercises that have better transfer than others, just do them at the appropriate time.

You may start thinking that all training should be based upon specificity. In certain models that would be fine. In Anatoliy’s models of periodization, everything is in all of the time—meaning that GPP, SPP, SDE, and the competitive exercise are in at all times. You’ll notice that it’s not SPP only, but that GPP is also included at all times. For more traditional models, the GPP phase needs to be there. This will help to prevent injury, and by increasing the strength and size of the GPP overall (strength, mobility, robustness), you seem to increase the SPP’s receptivity for adaptation.1

Some people will read a study like this and think that it’s telling us that all we need to do is SPP, so that’s all we are doing year-round. This is a mistake with the reader’s interpretation of what the authors are saying. (I know because I asked them.) The study shows that there are squats that are general and there are squats that are more specific. Both types of training (GPP and SPP) are needed, regardless of the periodization model you utilize. Even Bondarchuk, who is famous for specificity, included GPP in his program year-round. (SPP and even more specific types of training, such as the competitive exercise and Special Developmental Exercises, were included).

Why does the GPP phase need to be there if it doesn’t have as great of a transfer then? First, while it wasn’t as great, the authors clearly stated better transfer; they didn’t state that the squat didn’t transfer at all. Second, the phase does have a great amount to do with mobility, injury prevention, and base strength. These are all quite important qualities. The more mobile the athlete is and greater their base strength is, the greater they can push the SPP and, thus, achieve higher transfer.

There has to be balance, and when training is out of balance, so are the results. Share on XOne thing that I think we constantly do wrong is that we tend to overcorrect. As VBT has increased in popularity, people have started doing everything with it. As functional training came into vogue, every exercise was done on a Bosu, Airex, or Swiss ball. As power factor training came into vogue, every exercise was done as a partial. Balance is required for training—if we look back at the physiological aspect, we see that we can have adaptations to the Series Elastic Component (SEC) in the following ways13:

- To the muscle cell in terms of myofibril adaptations by increasing heavy chain myosin size (and the ability to increase its strength of holding onto the actin or resisting breaking apart from it); and

- Increases in the efficiency of the sarcoplasmic reticulum’s ability to absorb and release calcium, which allows the actin and myosin to interact with the troponin unlocking the receptor site for the tropomyosin to move and the actin to be grabbed.

Then two neural means are:

- Henneman’s size principle, where high-threshold motor units are preferentially recruited; and

- Rate coding, which deals with the speed at which the inter and intramuscular coordination aids in muscle contraction velocity.

There has to be balance, and when training is out of balance, so are the results.

One question that you may be asking right now is: “Where do I get more specific exercises?” I’d like to point you in the direction of two authors. The first is Anatoliy Bondarchuk, whose books, “Transfer of Training in Sports” and “Transfer of Training in Sports, Volume 2” had a great number of exercise charts showing how athletes responded to various exercises in the throws. For an interesting read, also check out his critique of the Soviet methods to see his views on their periodization models. The other is the work of Dr. Michael Yessis, who developed special exercises for the sprints and jumps. (Interestingly, he did push the ¼ and ½ squats in favor of the back squat for adaptation to the sprints and jumps, more than 30 years ago.) His books, “Build a Better Athlete” and “Biomechanics and Kinesiology of Exercise,” both contain a great number of special exercises with descriptions, pictures and their applications.

These two men, as authors and practitioners, have had a profound effect on the way I view training athletes. Specialized exercises are any exercises that elicit a greater transfer to the sport. There will be a large amount of carryover for exercises among sports, but there are also some sports that have specific exercises that are different.

Specialized exercises are any exercises that elicit a greater transfer to the sport. Share on XIn conclusion, there needs to be a great amount of balance in a program. We must realize that there are multiple ways to produce force, and ensure that all of these are being trained. We must realize that, when you focus on only one thing, something else will fall off. If we only do the general and negate the specific, we tend to not have as high end results. If we only do the specific and negate the general, we tend to get injured and not have as high results because there is no platform upon which to stand (GPP).

Again, while the ¼ and ½ squats do have the greatest transfer, the time to put them in is during the SPP phase of training (pre-season), as this will have the biggest impact on sprinting and jumping performance. The full squat should be done during the GPP phase of training (off-season), as this will have the biggest impact on mobility and general strength.

Not one of the variants is “better” than the other for the body. Rather, there are just times when it is better to do one of the variants over the others. All are needed; the question is when and where to put them for the greatest effect on the sport.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

[mashshare]

References

- Verkhoshansky V and Verkhoshansky N. Special Strength Training: Manual for coaches. Rome, Italy: Verkhoshansky.com, 2011.

- National Strength & Conditioning Association. Essentials of Strength Training and Conditioning. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics, 2000.

- Rhea MR, Kenn JG, Peterson MD, Massey D, Simão R, Marin PJ, Favero M, Cardozo, D and Krein, D. Joint-Angle Specific Strength Adaptations Influence Improvements in Power in Highly Trained Athletes. Human Movement 17: 43-49, 2016.

- Mann B and Austin D. Powerlifting: The complete guide to technique, training and competition. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics, 2012.

- Jacobson BH, Conchola EG, Glass RG, and Thompson BJ. Longitudinal Morphological and Performance Profiles for American, NCAA Division I Football Players. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research 27: 2347-2354. 2310.1519/JSC.2340b2013e31827fcc31827d, 2013

- Miller TA, White ED, Kinley KA, Congleton JJ, and Clark MJ. The effects of training history, player position, and body composition on exercise performance in collegiate football players. Journal of strength and conditioning research/National Strength & Conditioning Association 16: 44-49, 2002.

- Mann JB, Sayers, Stephen P, Cutchlow, Rohrk, Mayhew, Jerry. Longitudinal effect of traditional and velocity-based training on vertical jump power in college football players. Presented at NSCA National Conference, New Orleans, LA, 2016.

- Rhea MR, Kenn JG, and Dermody BM. Alterations in Speed of Squat Movement and the use of Accommodated Resistance Among College Athletes Training for Power. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research 23: 2645-2650. 2610.1519/JSC.2640b2013e3181b2643e2641b2646, 2009.

- Yessis M, PhD. Build a Better Athlete. Terre Haute, IN: Equilibrium Books, A Division of Wish Publishing, 2006.

- Zatsiorsky VM. Science and Practice of Strength Training. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics, 1995.

- Bondarchuk AP. Ypsilanti, MI: Ultimate Athlete Concepts, 2007.

- Bondarchuk AP. Champion School: A Model for Developing Elite Athletes. Ypsilanti, MI: Ultimate Athlete Concepts, 2015.

- Haff GG and Triplett NT. Essentials of Strength Training and Conditioning 4th Edition. Human Kinetics, 2015.