The strength coaching profession loves experimenting with fads that promise to give athletes an edge. We transitioned through Nautilus machines in the ’70s, jump shoes in the ’80s, slideboards in the ’90s…and now we have the Nordic curl. Finally, the answer to preventing hamstring pulls, particularly in sprinters.

Not so fast.

Don Chu, PhD, an accomplished jump coach and one of the foremost experts on plyometrics, introduced me to Nordic curls in the early ’80s during his weight training class. The exercise recently got a powerful jumpstart in the general fitness population when Ben “Kneesovertoesguy” Patrick began promoting it as part of his knee rehab program. Patrick has built a huge following, with more than 1.3 million YouTube subscribers and an appearance on the Joe Rogan show.

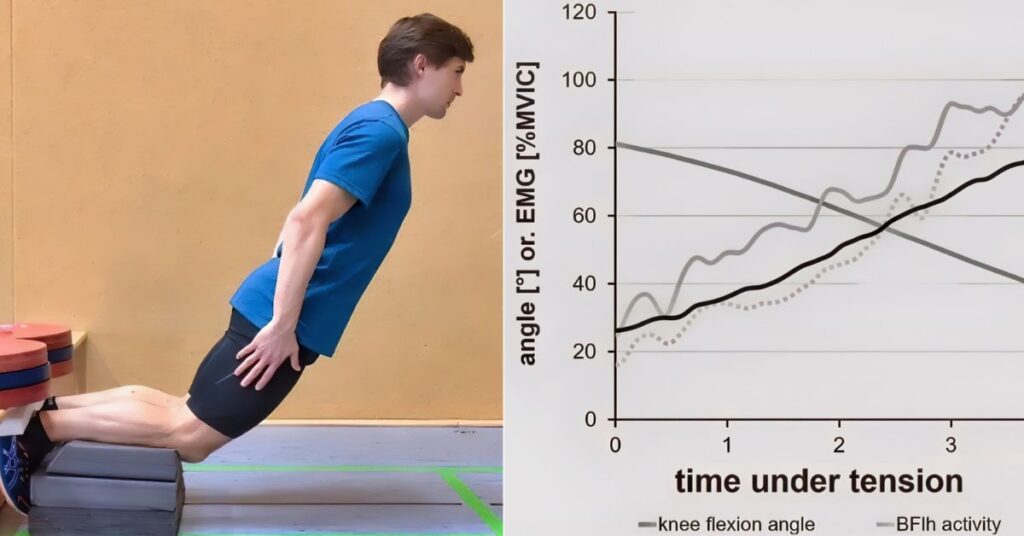

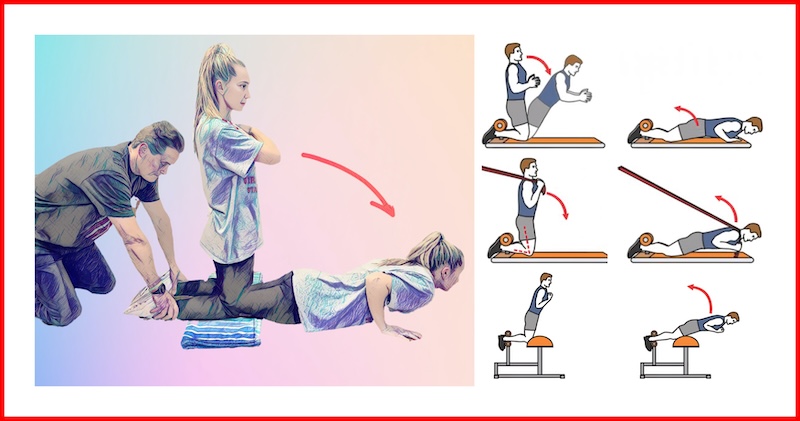

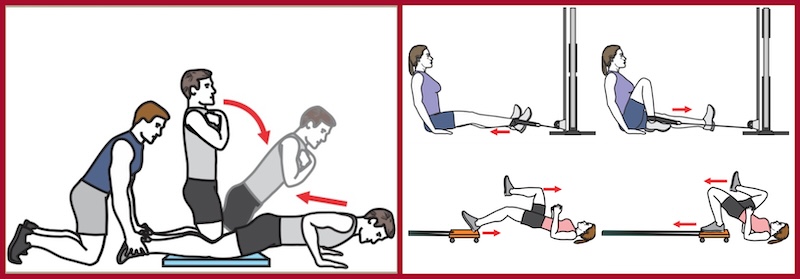

The basic Nordic curl starts with you kneeling on the floor/ground with a training partner anchoring your feet (see image 1 below). You should place a towel or pad under your knees for comfort. One suggestion I learned from German sports scientist Dr. Tobias Alt is to extend your knees over the edge of the pad to permit the patella to glide easily (see lead photo at top). You can place your hands across your chest or at your sides, but the best way is with your arms bent in a push-up position. This position makes it easier to catch yourself at the bottom and maintain high hamstring activation at the end of the movement.

With your upper legs perpendicular to the floor and your torso upright, slowly lower your legs and torso as a unit, catching yourself with your hands when you can no longer control the movement. When your hands touch the floor, immediately straighten your arms explosively (such as with a push-up) to return to the start.

The Nordic curl’s resistance curve is such that it’s rare for an athlete who has not trained on it for an extended period to perform it without collapsing at the midway point. Share on XThe exercise’s resistance curve is such that it’s rare for an athlete who has not trained on it for an extended period to perform it without collapsing at the midway point, much less return to the start without assistance. In Dr. Chu’s weight training class, one elite male long jumper could do it, and an elite female discus thrower who became a national weightlifting champion and American record holder got close.

To progress in the exercise, you can place a low platform in front of you to decrease your range of motion, reducing the height of the platform as you get stronger. There are also ways to modify the resistance curve to match your strength curve, such as using an elastic band, as shown in image 1. As the band stretches, it provides assistance at the end range.

For weight rooms with a healthy budget, plate-loaded Nordic curl machines adjust to your strength curve to permit a smoother motion. The best known is the Westside Inverse Curl machine®, patented and promoted by powerlifting legend Louie Simmons. The machine’s counterbalanced arm has a padded bar that rests in front of the chest, allowing you to increase the weight incrementally to make the movement easier.

At the advanced level, resistance can be increased by holding a weight plate across the chest or wearing a weighted vest. Because the exercise is so challenging, at first, additional resistance might only be used during the lowering phase (and then released during the concentric phase).

Before discussing some of the peer-reviewed research on the Nordic curl, let’s look at one theory about why the exercise can adversely affect sprinting ability and increase the risk of hamstring injuries.

Nordic Curls and the Speed Trap

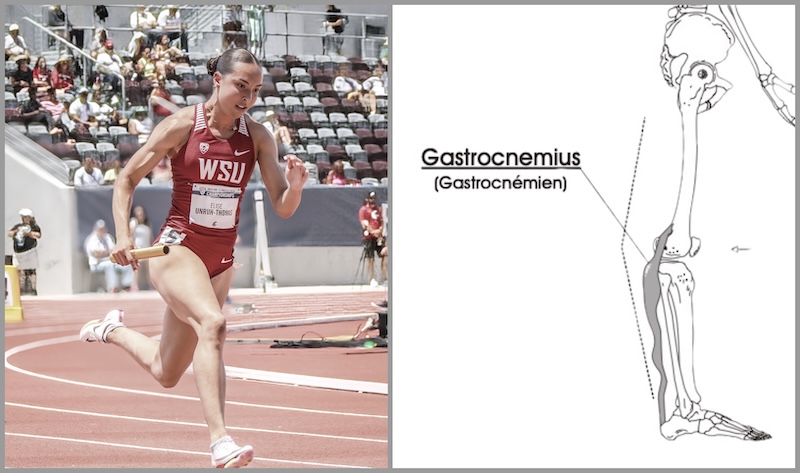

One of the most outspoken critics of the Nordic curl is weightlifting sports scientist Andrew “Bud” Charniga. Charniga says that although the exercise may have value for bodybuilding purposes, athletes shouldn’t do it. His central argument is based on the anatomy of the calves and their function.

The two primary calf muscles are the gastrocnemius (upper calf) and soleus (lower calf). Charniga says the gastrocnemius should be considered a thigh muscle because it overlaps the knee and contributes to knee flexion. These factors have implications for getting more out of stretching and muscle-building workouts. Let me explain.

For stretching, in the early ’90s, I attended a hands-on seminar by Bob Anderson in Colorado Springs. Anderson is the author of Stretching, which sold more than 33 million copies. Anderson told us that tightness in the calves is one of the limiting factors to stretching the hamstrings. Therefore, it makes sense to stretch the calves before stretching the hamstrings.

For muscle building, Canadian strength coach Charles Poliquin would use this knowledge of functional anatomy to increase the work of the hamstrings during leg curls.

Because you can lower more weight than you can lift in leg curls, the exercise’s eccentric (lowering) phase is not loaded maximally. To get around this limitation, Coach Poliquin would have you lift the weight with your feet dorsiflexed (toes pulled up) to enable the gastrocnemius to assist with knee flexion. Then, you would lower it with your feet plantarflexed (feet pointed down) to decrease the work of the calves and increase the work of the hamstrings.

As shown by these two examples, understanding the anatomical structure of the calves can improve your ability to stretch and strengthen the hamstrings. However, from a motor learning perspective, Charniga contends that the Nordic curl is a horrific exercise for sprinters.

Charniga says most hamstring injuries in sprinting occur during the late swing phase when your front leg is extended and just about to touch the ground. At this point, the long head of the biceps femoris completes the longest stretch of the three hamstring muscles (the others being the semitendinosus and semimembranosus). How can the hamstrings relax to extend the knee when the calves contract to produce the opposite effect? It can’t—something must give, and that’s usually the hamstrings.

There is probably no harm in occasionally performing the Nordic curl as a novelty challenge, such as with my experience in Dr. Chu’s class. However, the risks versus rewards of this exercise may not be acceptable, especially for high-level athletes. Let’s look at some research.

The Age of Misinformation

Many internet influencers have made extraordinary claims about the benefits of the Nordic curl, backing their claims with research studies. However, let’s read beyond the abstracts, starting with a meta-analysis on soccer injuries and the Nordic curl, which had this brain-teasing title: “Effect of Injury Prevention Programs that Include the Nordic Hamstring Exercise on Hamstring Injury Rates in Soccer Players: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.”

A meta-analysis makes the study on a topic easier for the reader by reviewing the results of numerous studies. The researchers of this study concluded: “Teams using injury prevention programs that included the NH (Nordic hamstring) exercise reduced hamstring injury rates up to 51% in the long term compared with the teams that did not use any injury prevention measures.” Impressive, but questions arise when you look closely at the Methods section.

Only five studies met the researcher’s requirements of the study, and in only one was the Nordic curl the only intervention (so, not so “meta”). Here is an example of the intervention protocol in one of the studies accepted for their review:

Hamstring Intervention Workout

Initial Running Drills

-

Jog

Hip-In

Hip-Out

Circle Partner

Shoulder Contact

Cut up and Back

Exercises

-

Plank

Side Plank

Eccentric Hamstring (Nordic Curl)

-

Single-Legged Balance

Squats

Jumps

Final Running Drills

-

Sprint

Bounding

Cut Side-to-Side

With so many exercises, how can anyone conclude that Nordic curls made a difference? Perhaps a reduction in injuries occurred despite doing the Nordic curl, a concern pointed out in the researcher’s comments: “Because we did not quantify physiologic variables, we cannot adequately determine the mechanism of decreased injury risk or identify the most effective part of the intervention program.” As for the single study where the Nordic curl was the only additional variable, the results were underwhelming because the researchers found that the Nordic curl “does not reduce hamstring injury severity.”

Many other studies on the Nordic curl have been performed, but some need to be looked at with skepticism. According to a 2022 review by Dr. Alt, “assessments and interventions suffered from imprecise reporting or lacking information regarding NHE (Nordic Hamstring Exercise) execution modalities and subsequent analyses.”

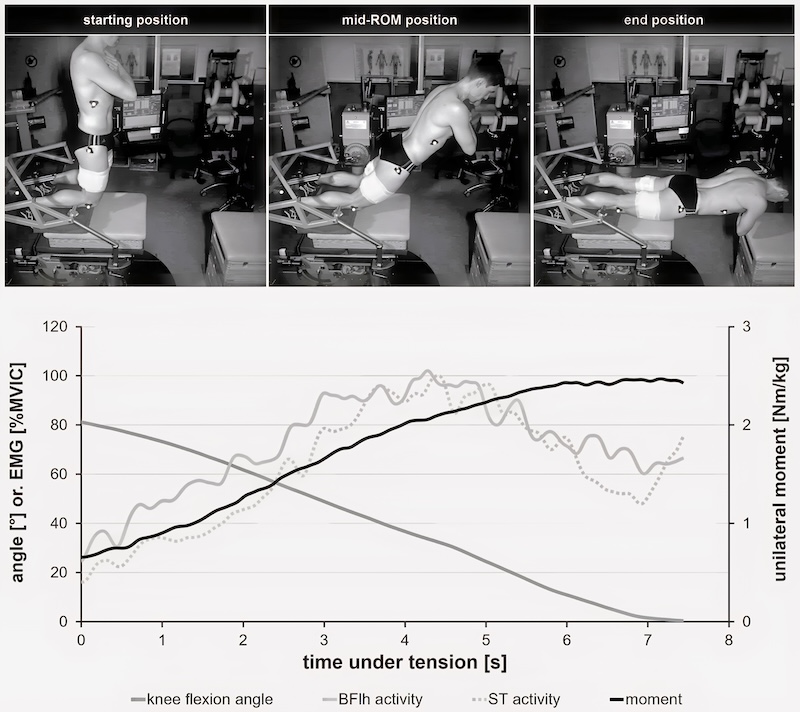

I asked Dr. Alt to expand on his opinion of the Nordic curl, and he replied, “The conventional Nordic curl does not evoke the full potential the way most people perform it, as only 30 percent of generated impulse is allocated to the first 45 degrees of knee extension…Alternatively, extended knee angles should be addressed with high intensity for suitable performance enhancement and effective injury prevention via assistance or guidance.”

Another factor to consider is that even though most strength coaches know about the Nordic curl exercise (and many are familiar with the research supporting it), where are real-world success stories?

Even though most strength coaches know about the Nordic curl exercise (and many are familiar with the research supporting it), where are the real-world success stories? Share on XIn soccer, consider the results of a 2022 study involving 3,909 soccer players from 54 teams in 20 European countries from 2001 to 2022. Rather than decreasing, the researchers found that hamstring injuries doubled during this period and that during the last eight seasons, “hamstring injury rates have increased both in training and match play.”

In American football, why haven’t hamstring injuries decreased in the NFL over the past decade? On average, about two dozen NFL players are sidelined every week in-season due to hamstring injuries. For example, 43 football players were sidelined with hamstring injuries before the start of the 2019 season, and between the 2018 and 2019 seasons, about 25 athletes could not play each week due to hamstring injuries. This trend continues today; for example, Charniga discovered that during one week in October 2023, 48 NFL players were sidelined with hamstring injuries.

But It Works…or Does It?

Again, with all the glowing testimonies about the Nordic curl being able to bulletproof the hamstrings against injury, why are hamstring injuries so prevalent and increasing in some sports? If you need more convincing with “evidenced-based practice” arguments, here are five more variables to reconsider the value of the Nordic curl:

1. Biomechanics

Gestalt is the theory that the sum of the parts is not as great as its organized whole, and in sports, gestalt may translate into “everything is connected.”

The Nordic curl isolates one function of the hamstrings: knee flexion. This may be great if you’re a bodybuilder, but it’s not how the legs work in sprinting. Share on XThe Nordic curl isolates one function of the hamstrings: knee flexion. This may be great if you’re a bodybuilder, but it’s not how the legs work in sprinting. As confirmed by researchers in one 2018 Special Communication in Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, “Accordingly, the hamstrings are stretched at both the knee and the hip joints during sprinting, but they are only stretched at the knee joint during NHE.”

As with the leg extension that isolates knee extension, the rigid knee flexion motion is not duplicated in sports, as concluded by one research 2019 study on Australian Rules Football (ARF). “The [NHE] movement does not replicate what is needed in the real world for ARF” and should be “included in a hamstring injury prevention program in this code with caution.” I would add that the fixed nature of the exercise immobilizes the muscles of the ankle used in running and jumping.

2. Force Production

The Nordic curl is performed slowly, so even though muscle mass can be increased, the elastic properties of the connective tissues are not used to increase force production. The prolonged time under tension that occurs during the exercise changes the organization of the contractile components of muscle fibers (pennation angle), reducing a muscle’s ability to produce force quickly.

In high-velocity movements such as sprinting, force is produced briefly, followed by a prolonged period of relaxation. “Sprinters are elastic, pulsating athletes. The fastest sprinters are the fastest relaxers, meaning they get their muscles to fire up quickly and then relax quickly,” says spine biomechanics expert Dr. Stuart McGill. “The same goes for weightlifters. Russian sports scientist Leonid Medvedev showed that the muscles of elite weightlifters relax six times faster than the average Muscovite walking around the street.”

For these reasons, the Nordic curl should be regarded primarily as a bodybuilding exercise, not an exercise to develop athletic fitness. Let’s look at some research.

Force is measured by the equation: Force = Mass x Acceleration, and peak forces in sprinting can reach 8x body weight. Although the Nordic curl is prescribed to deal with the high-velocity forces that occur in sprinting, researchers who evaluated the Nordic curl concluded in a 2021 study, “Overall, peak hamstring force during NHE (Nordic Hamstring Exercise) was not comparable to the peak hamstring force during sprinting.” There’s more.

One 2019 study examined how the Nordic curl affected sprint performance. The researchers concluded, “The NHE group reported trivial improvements in sprint performance,” and “sprint training also produced greater perceptions of soreness than the NHE.” Then there’s a 2017 study where researchers found that a six-week Nordic curl intervention program increased muscle mass but “did not significantly increase eccentric hamstring strength as expected.” In other words, the NHE does not improve sprint performance or develop eccentric strength as well as sprinting does. Besides sprinting, sprinting, and sprinting some more (which can be impractical in cold-weather environments), one alternative is flywheel training.

In other words, the Nordic curl doesn’t improve sprint performance or develop eccentric strength as well as sprinting does. Share on X

Because eccentric contractions produce the highest muscle contractions, a flywheel device can provide eccentric overload to achieve these peak forces by multiplying the force achieved during the concentric contraction. Video 1 shows a kBox being used to produce eccentric overload rapidly, one performed without assistance and the other with assistance. Artur Pacek, MS, CSCS, PhD candidate, an elite strength coach from Poland who has worked extensively with Knox and his athletes, produced the videos and the data.

What’s unique about these two videos is they show how improving stability—in this case, holding onto a barbell—can increase force production. The non-supported version could be considered more sport-specific, as the stability would transfer better to lateral movements, but the supported version would produce more force. Thus, a workout to do both could begin with unsupported squats and finish with supported squats to increase force production.

Video 1. Flywheel resistance training devices can provide high levels of an eccentric load to deal with the high forces that occur in sprinting. This analysis shows that higher force levels can be achieved in the squat when athletes increase their stability by holding onto a sturdy object. (Videos courtesy Artur Pacek, MS, CSCS, PhD candidate)

3. Range of Motion

Some internet fitness influencers claim the Nordic curl strengthens the hamstrings through a full range of motion. It can’t. The Nordic curl starts with your thighs perpendicular to the floor, so it cannot work the biceps femoris through a complete range of motion.

Some internet fitness influencers claim the Nordic curl strengthens the hamstrings through a full range of motion. It can’t. Share on XIn contrast, consider the supine leg curl with cables and roller boards that enable the heel to touch the glutes in the peak contracted position shown in image 5: exercises that can also be performed with flywheel units. One advantage of these variations is the working leg can be rotated internally and externally rather than being held rigid in one movement pattern as with the Nordic curl. Changing the lines of pull allows for more complete muscular development. They also don’t restrict the movement of the patella as occurs with the conventional Nordic curl.

Also, because gravity applies force vertically downward, there is no resistance until several degrees of motion are achieved. If you observe the training of elite bodybuilders, it is often characterized by partial-range exercises. Partial-range exercises, popular with bodybuilders to overload all points of an athlete’s strength curve, also change the pennation angle, affecting the ability of the hamstrings to exert force.

4. Athletic Testing

The Nordic curl is occasionally used to test strength, but what muscles does the exercise test? Is the exercise testing the strength of the calves or the hamstrings, and what are the contributions of each? Further, in what athletic movements is this motion duplicated? What sport is performed from a kneeling position with the lower limbs and ankles immobilized—kayaking?

5. Knee Stress

Compared to multi-joint exercises where stress is distributed over many structures, the Nordic curl is an isolation exercise focusing on a single structure. Strength coach and posturologist Paul Gagné addresses this topic. Gagné has trained more than 500 NHL players and worked with Dr. Guy Voyer, a famous osteopath who gave seminars on knee injuries (which I attended), and he is not a fan of Nordic curls.

“The popliteus (a major muscle involved in knee stability) gets really hammered, especially at the bottom position where the knee has no give,” says Gagné. “I’ve rarely seen people with good technique. They lack control at the bottom of the movement—it’s dangerous.” He adds that the Nordic curl places a high level of stress on the meniscus and a chronic inflammation condition called Housemaid’s Knee (prepatellar bursitis).

Don’t Buy What They’re Selling

Social media has given us access to considerable information about athletic fitness training, but the downside is that some of what we read, see, and hear is misinformation. It’s one thing for a popular internet influencer (and even a research study) to suggest that an exercise will produce remarkable results in athletic performance and reduce injury, but then there’s reality. Such is the case with the bill of goods we’ve been sold with the Nordic curl.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

Alt T, Personal Communication, 1/4/24.

Charniga B. “Hamstring Injury: Prophylaxis Fallacies in Sport,” Sportivnypress.com, 6/29/21.

Al Attar WSA, et al. “Effect of Injury Prevention Programs that Include the Nordic Hamstring Exercise on Hamstring Injury Rates in Soccer Players: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Medicine. May 2017;47(5):907–916.

Alt T, et al. “Quo Vadis Nordic Hamstring Exercise-Related Research? – A Scoping Review Revealing the Need for Improved Methodology and Reporting.” International Journal of Environmental Research in Public Health. September 7, 2022;19(18).

Ekstrand J. “Hamstring injury rates have increased during recent seasons and now constitute 24% of all injuries in men’s professional football: the UEFA Elite Club Injury Study from 2001/03 to 2021/22. British Journal of Sports Medicine. December 6, 2022;57:292–298.

Afonso J, et al. The Hamstrings: Anatomic and Physiologic Variations and Their Potential Relationships With Injury Risk. Frontiers in Physiology. July 7, 2021;12.

Charniga B, Personal Communication, 1/3/24.

Li Li and Ruan M. “Nordic Exercise Should Not Be Used for Predictive Modeling of Hamstring Injuries,” Special Communication. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. December 2018;50(12).

Milanese S, et al. “Hamstring injuries and Australian Rules football: over-reliance on Nordic hamstring exercises as a preventive measure?” Journal of Sports Medicine. July 23, 2019;10:99–105.

McGill S. “An Approach to Pain-Free Training for Track Athletes with Stuart McGill.” SimpliFaster. 1 December 2023.

Ruan M, et al. “The Relationship Between the Contact Force at the Ankle Hook and the Hamstring Muscle Force During the Nordic Hamstring Exercise. Frontiers in Physiology. March 9, 2021;12.

Freeman BW, et al. “The effects of sprint training and the Nordic hamstring exercise on eccentric hamstring strength and sprint performance in adolescent athletes.” Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness. July 2019;59(7):1119–1125.

Alt T, et al. “What Are We Aiming for in Eccentric Hamstring Training: Angle-Specific Control or Supramaximal Stimulus?” Journal of Sport Rehabilitation. June 20, 2023;32(7):782–789.

Pacek A. Personal Communication. 12/20/23.

Gagné P. Personal Communication. 12/15/23.

Good read.