When I started writing for Iron Game publications a half-century ago, I championed the cause that squats would not damage the knees. With the preponderance of research studies since then dispelling misinformation about the King of Lifts, you would think this case would be closed. Not quite.

From my perspective, strength coaches rarely have their athletes perform rock-bottom squats. As for cleans that involve rebounding out of the low catch position…ah, not a chance. Instead, many are often content to focus their leg training on partial-range step-ups, high hex bar deadlifts, and the so-called Bulgarian split squat.

Let’s see how we got here and explore the renewed interest in “knees over toes” exercises, starting with a tribute to the first champion of the squat, Paul Anderson.

(Lead image courtesy of Ben Patrick)

The Squat King

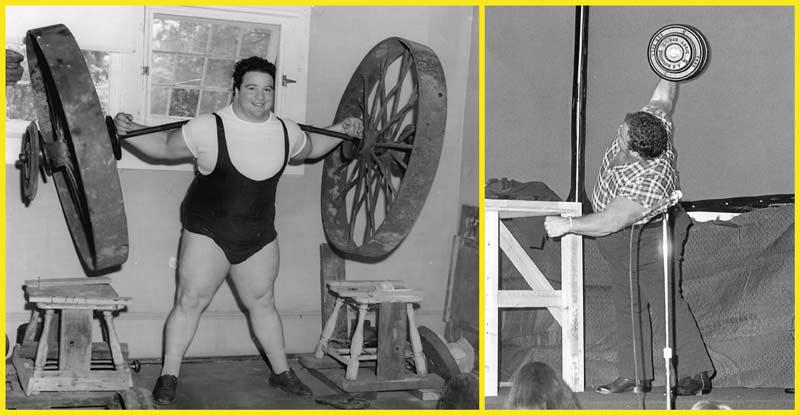

As a teenager, I purchased a copy of Paul Anderson’s book of training methods, which he graciously autographed. Why did I invest in a book by someone who encouraged me to squat heavy and drink cow’s blood? Because it was written by one of the strongest men in history.

Born in 1932, Anderson won a gold medal in the 1956 Olympics in weightlifting, but what captured the attention of the Iron Game community were his accomplishments in the squat. As a teenager, Anderson stood 5 feet 9 1/2 inches, sported 33-inch thighs, and squatted over 500 pounds. When he was 20, he unofficially squatted 660—30.5 pounds over the world record. In 1954, he squatted 820 and did quarter squats with 1,800 pounds. Anderson’s thighs grew to 36 inches, and his body weight to 360. Performing as a professional strongman, Anderson eventually squatted 900 pounds for 10 reps and 1,206 pounds for a 1RM.

In Anderson’s era, the strength coaching profession was in its infancy, and few athletes lifted weights. No one cared how weightlifters or any other athletes squatted. Share on X

In Anderson’s era, the strength coaching profession was in its infancy, and few athletes lifted weights. No one cared how weightlifters or any other athletes squatted—until 1961. That was the year Karl K. Klein’s questionable study about the association between squats and knee stability was published. Note the word “questionable.”

One of the subjects in Klein’s study was Bill Starr. Starr broke the world record in the Olympic press and wrote the strength training classic, The Strongest Shall Survive. Starr said Klein measured knee stability by applying manual pressure to a metal device that extended above and below the subject’s knee.

In a letter published in Strength and Health magazine in 1963, Starr said the study was not double-blind because Klein would ask the subjects if they did squats before he applied pressure. “The gadget which he placed on the lifters’ knees could be manipulated by the examiner to obtain any reading that he so desired,” said Starr. He added that many lifters quit the experiment “since he was exerting so much pressure that he hurt their knees.”

Several years later, sports science researcher Earle J. Meyers tried to replicate the study using a copy of Klein’s testing device. He concluded that “the deep squat and half-squat exercises did not produce significant differences in their effect on collateral ligament stretch, quadriceps strength, or knee joint flexibility.”

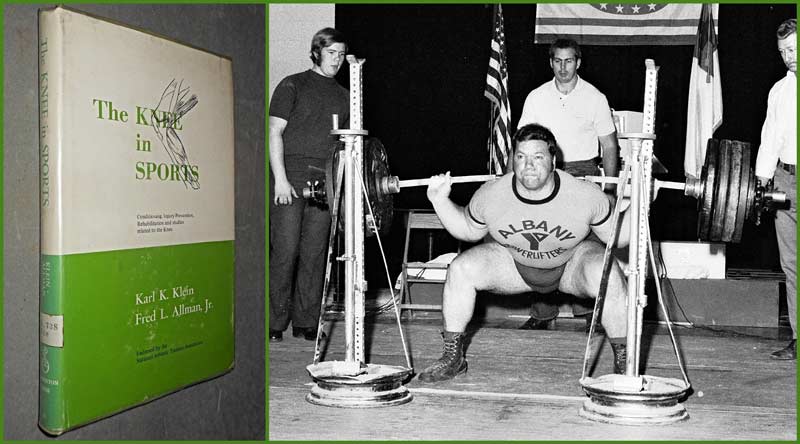

Klein expanded on his work with a book he co-authored with Dr. Fred Allman, Jr., in 1969 called The Knee in Sports. Although Klein was fine with the parallel squats that would pass in many of today’s powerlifting federations, the message passed on to the sports and medical communities was that squats—any squats— were bad for the knees.

Eventually, the scientific community countered the squat stability issue with research studies and position papers that expanded on Meyers’ work. One of the most prominent researchers on the subject was sports scientist Dr. Mike Stone, a former weightlifter. Stone and Jeff Chandler, Ed.D., co-authored a position paper on the squat endorsed by the National Strength and Conditioning Association (NSCA) in 1991. Extensively referenced, the paper concluded, “Squats, when performed correctly and with appropriate supervision, are not only safe but may be a significant deterrent to knee injuries.”

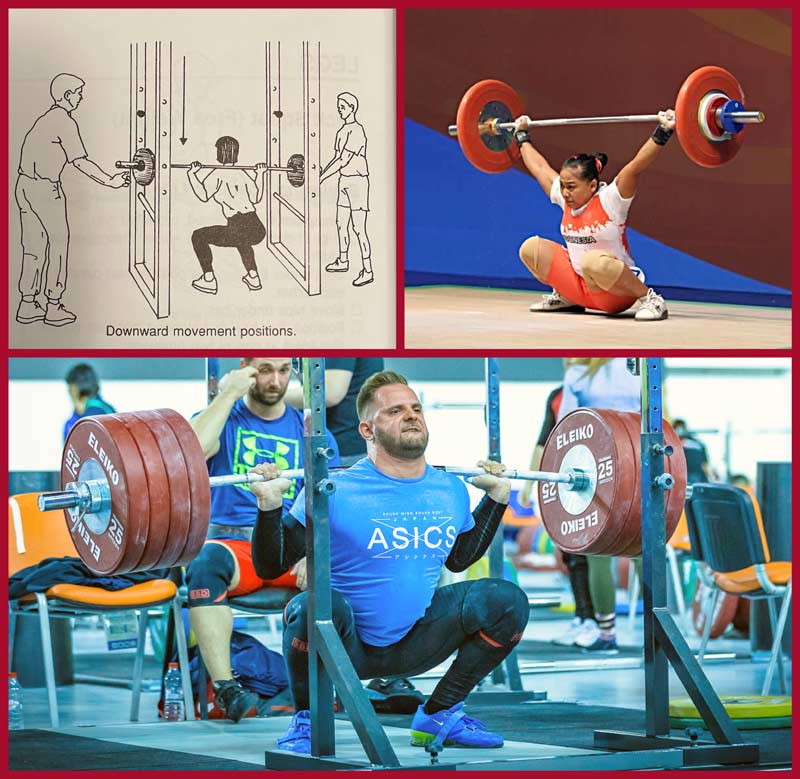

Despite the position paper, the NSCA adopted a conservative approach to squat depth by recommending that the knees should not extend beyond the toes. Share on XThis position paper helped the cause, but for some reason, the NSCA adopted a conservative approach to squat depth by recommending that the knees should not extend beyond the toes. In their position paper, the general recommendation was that the trainee should “descend only until the tops of the thighs are parallel to the floor or slightly below” and “the shin should remain as vertical as possible to reduce shear forces at the knee. Maximal forward movement of the knees should place them no more than slightly in front of the toes.” These recommendations were reflected in study materials for their strength coaching certification, such as their textbook, Essentials of Strength Training and Conditioning.

In the description of the squat in this NSCA textbook, the accompanying drawing and text recommended only squatting until the tops of the thighs are parallel to the floor (image 3) and not bouncing out of the bottom. Now consider the low squat positions of an elite weightlifter snatching and an elite weightlifter squatting in image 3. Why is the NSCA apparently okay with the sport of weightlifting but not with the squatting depth performed by weightlifters?

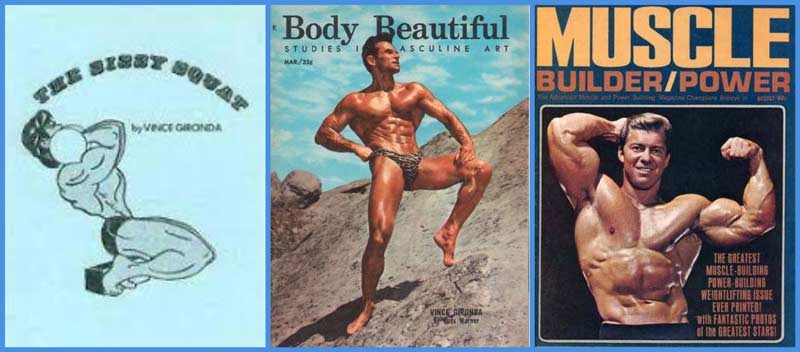

While this debate was happening in athletic fitness training, the bodybuilding world took a different path, led by Vince Gironda.

The Gluteless Training Guru

Gironda was an accomplished bodybuilder who also “walked the talk” as a personal trainer. He coached Larry Scott, the first Mr. Olympia, and earned the nickname “Trainer to the Stars” for his work with Hollywood celebrities. His clientele included Cher, Clint Eastwood, James Garner, Burt Reynolds, Denzel Washington, and Carl Weathers.

Gironda believed conventional squats widened the hips, making a physique look blocky. “Full squats build the gluteus maximus (buttocks) by the forward position of the upper body and the depth of the movement.” In many leg exercises, these requirements resulted in the knees extending far over the toes. The sissy squat was his favorite, and he even wrote a book called The Sissy Squat.

Gironda’s barbell sissy squat was awkward and required considerable balance, reducing how much resistance could be used. However, many weight training machines available today enable you to easily perform exercises that allow you to extend your knees over the toes and do not involve a forward torso position.

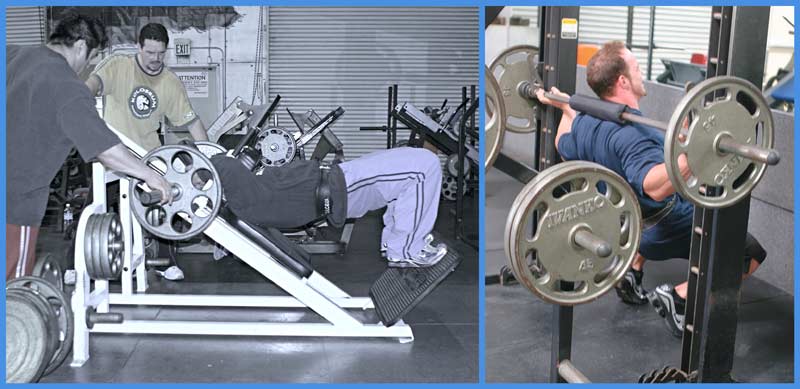

Many weight training machines available today enable you to easily perform exercises that allow you to extend your knees over the toes and do not involve a forward torso position. Share on XImage 5 shows examples of modern bodybuilders performing exercises on machines according to Gironda’s guidelines.

You’ll notice in both these exercises that the knees extend well in front of the toes and the heels are lifted, as in the Gironda sissy squat. However, because the resistance slides on guided rails in these two exercises, the trainee can put maximum effort into working the quads. Also, advanced training methods, including heavy eccentrics and force reps, can easily be performed with these machines to overload all areas of a muscle’s strength curve.

One criticism of the leg training methods that exclude the involvement of the glutes, particularly leg extensions, is that the hamstrings are less active than in the squat. This inactivity puts excessive stress on the anterior cruciate ligament. During a conventional squat, the hamstrings help neutralize the pull of the quadriceps to cause anterior tibial translation, a shear force that tries to pry the joint apart.

A complementary knees-over-toes timeline could be attributed to Canadian strength coach Charles R. Poliquin (image 6) and his approach to knee rehabilitation. As Coach Poliquin’s primary editor for over two decades, I had a front-row seat to this experience.

The VMO Distraction

Over 30 years ago, Poliquin told me about his general approach to knee rehabilitation. It focused on first targeting the quad muscles medial (inside) of the knee with partial-range exercises, then gradually working the entire quad by increasing the range of motion. He called the specific muscle he wanted to work the VMO, an acronym for vastus medialis oblique. (FYI: We now know that this muscle can be divided into two sections, the vastus medialis longus and the vastus medialis obliquus, which have different lines of pull on the knee.)

Poliquin used this approach to leg training with the Canadian National Women’s Volleyball Team in the ’80s. When Poliquin started working with these athletes, most of them suffered from patellar tendinitis, a painful inflammation of the patellar tendon.

Poliquin told me that because volleyball players seldom bend their legs through a full range of motion, the muscles that exert an outward pull on the kneecap become stronger than those that pull the knee inward. This imbalance affected the tracking of the kneecap, causing this overuse injury.

Poliquin stressed the importance of starting athletes with full “knees-over-toes” squats at an early training age to keep the knees healthy. Share on XHere is the three-step progression Poliquin told me he used with these athletes:

- Petersen Step-Up. The Petersen step-up is a partial step-up to target the muscles on the knee’s medial (inside) portion. It starts with the working leg a few inches off the floor, the heel elevated, and the knee slightly bent. As the leg straightens, the athlete rocks backward to minimize the shearing stress on the knee (thus, it can be performed in the early stages of rehab). The descent involves lowering the heel and raising it again before returning to the start.

-

Because so many people did not perform the Petersen step-up correctly (thanks partly to the countless YouTube videos performing it wrong), Poliquin later substituted it with a simpler version called the “Poliquin step-up.” One difference between the Poliquin and the Petersen step-up is that the entire foot of the working leg is placed on a wedge board. Also, to focus more on the working leg in both exercises, Poliquin would have you lift the toes of the trailing leg to avoid pushing off with that leg.

- Front Step-Up. When an athlete could perform a Petersen step-up with the working leg at shin level, it was time to progress to the front step-up. He would have you start with the knee slightly below the crease of the hip. Again, the toes of the trailing leg were lifted. When the athlete could comfortably perform step-ups with the upper thigh parallel to the floor, the next progression would be the Australian squat.

- Australian Squat. High-bar full squats were the final step in this knee rehab protocol. The term “full” means descending so that the hamstrings cover the calves and the knees travel in front of the toes. This contrasts with the low-bar parallel squats performed by powerlifters that minimize the involvement of the quads. According to Poliquin, the further the bar moves down the back, the more the load shifts away from the quads and onto the glutes, erector spinae, and hamstrings.

One squat variation Poliquin often prescribed during this phase was the Australian squat (video 1), which emphasizes the quads in the external range (i.e., the area closest to the hip). It also reduces the compression forces on the spine because the torso remains vertical longer. Poliquin showed me this variation over 30 years ago, so I had always called it the Poliquin squat. However, I recently heard it was initially called the Australian squat, so I stand corrected.

Video 1. The Australian squat emphasizes the quadriceps muscles closer to the hip. It begins with a slow descent and the knees extending in front of the toes.

Poliquin stressed the importance of starting athletes with full “knees-over-toes” squats at an early training age to keep the knees healthy. He also extended his approach to other popular leg exercises, particularly lunges and split squats. Although it took many years after Poliquin presented his opinions on leg training, research proved that the highest compressive forces on the knee were at 90 degrees. There’s more.

A 2013 review of 164 research papers concluded that there was no greater risk of developing chondromalacia, osteoarthritis, or osteochondritis performing deep squats than with quarter and half squats. Share on XA 2013 review of 164 research papers concluded that there was no greater risk of developing chondromalacia, osteoarthritis, or osteochondritis performing deep squats than with quarter and half squats. Further, the researchers concluded that quarter and half squats could contribute to long-term damage to the knees and spine. “With the same load configuration as in the deep squat, half and quarter squat training with comparatively supra-maximal loads will favour degenerative changes in the knee joints and spinal joints in the long term. Provided that technique is learned accurately under expert supervision and with progressive training loads, the deep squat presents an effective training exercise for protection against injuries and strengthening of the lower extremity.”

Charles R. Poliquin passed away on September 26, 2018, but in recent years, internet influencer Ben Patrick (lead photo) has been preserving his legacy by promoting Poliquin’s approach to knee rehabilitation and training.

Knees Over Toes Goes Viral

Patrick was a promising college basketball player who suffered chronic knee pain that led to numerous surgeries. Poliquin’s work impressed Patrick so much that he booked a phone consultation. Patrick followed Poliquin’s advice; soon, Patrick’s knees became pain-free, and his jumping ability improved dramatically.

Patrick shared his success on social media and created a fitness consulting company incorporating many of Poliquin’s ideas. At last count, Patrick’s YouTube channel has north of a million subscribers, and his followers include 2,291 success stories. Because of his emphasis on full-range leg exercises, Patrick took on the nickname of the “Kneesovertoesguy.”

One benefit of full-range exercises is that they increase the strength, mobility, and stability of the ankles. Share on XOne benefit of full-range exercises is that they increase the ankles’ strength, mobility, and stability. Check out video 2 of my two former athletes, Sesely and Nicole. In it, Sesely performs the snatch, and Nicole performs the clean and jerk. Sesely demonstrates remarkable ankle strength and stability in saving her lift, and Nicole is shown using the elastic properties of the Achilles to help her bounce out of a heavy clean.

Video 2: The first female lifter in this video shows remarkable ankle strength and stability while saving a snatch. The second lifter demonstrates the elastic properties of the Achilles by bouncing out of a heavy clean. Both lifters, coached by the author, broke New England weightlifting records.

Besides being able to lift impressive weights with acrobatic saves, full-range exercises performed quickly help prevent injuries, particularly to the ankles and Achilles tendon. According to strength coach and posturologist Paul Gagné, ankle mobility reduces the stress on the foot and Achilles, thus reducing the risk of injury. Case in point: weightlifters.

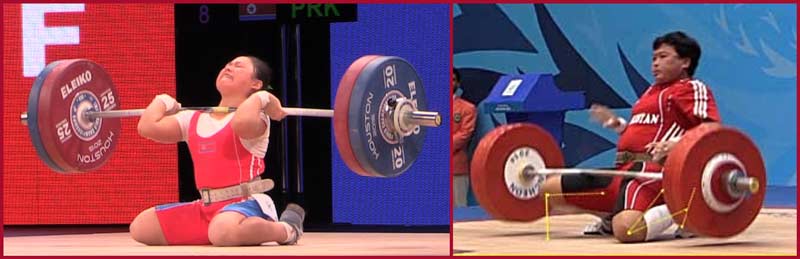

Ankle, Achilles tendon, and foot injuries are rare in weightlifting, despite weightlifting shoes being low cut and providing minimal lateral support. Note the female athletes in image 8. The first photo is of a 105-pound lifter collapsing awkwardly with 268 pounds, placing her quads and ankles in a position of extreme stress. The second photo shows a 165-pound lifter dropping 297 pounds on her legs. Neither lifter was injured due to a protective mechanism called the “reflective release.”

“Reflexive release is an extremely rapid, complex switching from muscle tension to relaxation in response to some sudden loss of equilibrium, fall, injury or other unanticipated event in sport,” says weightlifting sports scientist Bud Charniga. “This mechanism precludes conscious effort to move or fall in such a way to avoid injury. Circumstances where reflexive release can be effective in injury avoidance are too fast for mind–to–muscle actions to be useful.” Charniga adds that the isometric and near-isometric methods commonly used by bodybuilders and powerlifters would suppress the reflective release mechanism.

Contrast those results with the number of NFL and NBA players who injure their ankles and tear their Achilles tendons without being touched. Or the fact that an estimated 70%–75% of all ankle sprains and strains are considered non-contact injuries. (For a deep dive on this topic, check out my article on ACL and Achilles injuries.) There’s more.

Besides preventing injuries, Gagné says ankle mobility is a critical component of speed and jumping ability. “One indicator of elastic strength is your ability to lift your big toe and dorsiflex the foot, which your flexor hallucis longus and extensor hallucis brevis muscles control. The higher you can raise your big toe without strain, the more elasticity you have in the foot and the Achilles. And the more elastic energy you have, the higher you can jump and the faster you can run.”

How do you develop high levels of elastic strength if you’re not a weightlifter? I have a few suggestions. Share on XSo, how do you develop high levels of elastic strength if you’re not a weightlifter? I have a few suggestions.

Train the Way You’re Going to Fight

One problem with recommending full-range exercises is that many athletes can only perform a partial squat due to a lack of ankle flexibility. One dynamic stretch I’ve used with sprinters and cross country runners at Brown University to address this issue is to have them perform a squat while standing on a wedge board (aka slant board) with the smaller angle facing you (video 3). It’s a simple, effective way to stretch both calf muscles: the gastrocnemius (upper calf) and the soleus (lower calf). For best results, perform this movement barefoot.

For variety, change the position of the feet. Pointing your feet inward increases the stretch on the calf’s lateral (outside) part, while pointing the feet outward works the calf’s inside (medial) part. Gagné says a beginner should start with an angle of no more than 5 degrees. “You generally do not want beginners to use more than a 5-degree angle because a higher wedge may put too much pressure on the Achilles tendon and jam the subtalar joint.”

Because most squat wedge boards are at about 20 degrees, one way to compensate is to stand further away from the edge, starting with the ball of the foot on the board. As your flexibility improves, move up on the board.

Video 3: A wedge board can be used to perform a dynamic stretch for both calf muscles: the gastrocnemius and soleus. (This soccer photo and the modeling photo in video 1 by Joel Morel.)

When mobility improves, a progressive next step would be ankle squats (video 4), which strengthen both calf muscles through a full range of motion. These are performed with your heels a few inches apart and feet and knees flared out. You squat all the way down and only come three-quarters of the way up. Max weights are not used.

Video 4: Ankle squats are an effective exercise to strengthen the gastrocnemius and soleus through a full range of motion.

Charniga saw elite weightlifters performing this exercise in 1974 and had this to say: “This technique of squatting where the shins are actively tilted forward with flexing knees and near vertical trunk incorporates the soleus and other single-joint plantar flexion muscles of the shank. These muscles contract eccentrically as the Achilles tendon stretches, accumulating elastic/strain energy in the process. When the athlete reverses direction, the aforesaid soleus and other single-joint plantar flexion muscles perform what can be described as a reverse-origin insertion contraction. That is to say the origin of these muscles in the middle of the shank moves towards the insertion on the heel.”

This last statement should be of interest to strength coaches who have their athletes spend their limited training time on isolation exercises for the tibialis anterior, such as the dynamic axel resistance device introduced by Robert Gajda in Total Body Training, a book he co-authored with Richard H. Dominguez, MD. The tibialis anterior muscle helps a weightlifter move under the barbell quickly when their feet are off the platform (image 9, left) and assists in moving the shin forward when the foot is on the floor. Note the development of this muscle (along with the calves) of a weightlifter in image 9 (right). Performing weightlifting movements would make such isolation training redundant.

Is there a downside to using wedge boards? Yes, particularly if these exercises are performed instead of conventional lifts for extended periods.

“If heels-elevated exercises are used occasionally to develop more muscle around the knee joint, fine,” says Gagné. “But overusing it creates less ankle mobility because you’re in a state of semi-plantarflexion.” Further, according to a 2003 study published in the Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research (Fry et al.), restricted ankle motion increases the stress on the hips and lower back. There’s more.

If you’re an athlete seeking to perform at peak levels with minimal risk of injury, take measures to improve your ankle mobility and focus on squatting heavy and squatting deep. Share on XGagné says using a wedge board to push the knee further over the toes than they can go with the feet on the floor may damage the knees. “Removing the foot from the equation creates large shearing forces on the patella tendon, which may lead to tendonitis and ligament laxity,” says Gagné.

If you use wedge boards to occasionally help you achieve higher levels of quadriceps development, particularly around the knee, you should be okay. If you’re an athlete seeking to perform at peak levels with minimal risk of injury, take measures to improve your ankle mobility and focus on squatting heavy and squatting deep!

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

Strossen, RJ. Paul Anderson: The Mightiest Minister. Ironmind Enterprises, May 1, 1999.

Klein, Karl. “The deep squat exercise as utilized in weight training for athletics and its effects on the ligaments of the knee.” Journal of the Association of Physical and Mental Rehabilitation. 1961;15:6–11.

Todd, TR. “Karl Klein and the Squat.” National Strength and Conditioning Association Journal. 1984 June;6:26–31. (Correction: Ref 32: The last name of the journal title should be Rehabilitation.)

Starr, B. “Letter to the Editor.” Strength and Health, August 1963.

Meyers, EJ. “Effect of selected exercise variables on ligament stability and flexibility of the knee.” Research Quarterly. 1971;42(4):411–422.

Klein, KK and Allman, Fred L. The Knee in Sports. Jenkins Publishing Company, January 1, 1969.

Stone, MH and Chandler, JT. “NSCA Position Paper: The Squat Exercise in Athletic Conditioning.” National Strength and Conditioning Association Journal. 1991;13(5):51–58.

Baechle, TR. (Editor). Essentials of Strength Training and Conditioning. Human Kinetics, pp. 369–370, 1994.

Gironda, V. The Sissy Squat. January 1, 1975.

Hartmann H, Wirth K, and Klusemann M. “Analysis of the load on the knee joint and vertebral column with changes in squatting depth and weight load.” Sports Medicine. 2013 Oct;43(10):993–1008.

Gagné, P. Personal Communication, June 5, 2023.

Charniga, B. “Should Female Weightlifters Be Injury Prone?” Sportivny Press, January 23, 2018.

Charniga, B. “Practical solutions to the problem of Achilles rupture and the proliferation of injuries to the lower extremities of football players.” Sportivny Press, February 17, 2017.

Dominguez, RH and Gajda, R. Total Body Training, Warner Books, pp. 247–248. 1982.

Fry AC, Smith JC, and Schilling BK. “Effect of Knee Position on Hip and Knee Torques During the Barbell Squat.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 2003;17(4):629–633.