Each year, the strength-specific science on the use of accommodating resistance grows, but the practice seems to stay disappointingly stagnant with coaches and athletes. Typically, we see the same approach of adding bands to squats to help with max strength, or using chains to help bring up a bench press that may be lagging. Occasionally, a coach will support the use of bands and chains as a replacement to Olympic lifts, almost as an either/or option for power development.

This article, however, won’t simply hash out old ideas disguised to look novel and different. It will provide practical applications for accommodating resistance that I have used with novice to high-level college and professional athletes over the last few years, validated by sports technology. It breaks down what I feel are the best and most applicable methods for nearly all levels.

It’s time to move away from the old notion that accommodating resistance is only for the elite. I’ll state, however, that it is not a smart idea to rush into any method of training, and the use of these methods should still be part of a greater plan as a whole. By no means is this list exhaustive, and I don’t claim that this is the definitive guide for strength coaches, but I do think it provides a solid argument for incorporating the methods listed below.

Several great publications by coaches and researchers really raised the standard on using variable or accommodating resistance, but the small nuances are necessary for the technique to really make a change. What separates this article from others is its authenticity. I’ve used what is outlined here with a number of NFL, MLB, and college athletes, and achieved actual results. If you are serious about taking bands and chains to the next level, this article backs up its recommendations with science and examples of the proper implementation of the exercises.

When Bands and Chains Are Just Not a Good Idea

I don’t recommend that everyone use bands and chains, and I actually warn against their use because variable resistance is designed to overload more and that could be a problem with inexperienced athletes and coaches. When safely employed, bands and chains work, but only if the athletes can do the fundamentals really well. I hate blaming tools for injury when the fault is usually the user, but in this day of Instagram stars, we must be extra cautious with training recommendations. If you are in a situation where the proper coaching ratio is not available, don’t use variable resistance. Intense overload is a mature and demanding training option, so I recommend just doing what you can and not worrying about adding chains and bands to your training equation.

If you don’t have the proper coaching ratio, don’t use variable resistance, says @ShaneDavs. Share on XThe final warning is simply this: If you don’t put in the time and effort to properly design training and just wish to spice it up or add a trick to the trade, this isn’t for you. Training with accommodating resistance requires a lot of prep work. Bands and chains are not dangerous, but anything that adds force and complexity can be hazardous to the wrong users. You can’t treat bands and chains as “weight room toys”—they are advanced tools for professionals.

My Personal Thought Process on the Methods Listed

I wrote this article to focus on unfiltered concepts instead of listing exercise variations or cool workouts. It’s popular to list workouts, make up a new movement, or share “progressions” of movement, but I would rather share what I know works very well and let you apply it in a way that fits your best interests. More methods exist than those compiled below, but if you add a few of the approaches listed you will reap big improvements to whatever program you use.

I co-own and run a private training facility and we have a small staff of experienced coaches, so keep that in mind when reading this article. Our business is about “craft coaching,” not mass production of one-size-fits-all templates. If you are not able to write customized or semi-custom training programs, bands and chains may not work with your situation and would perhaps be better implemented with just a subset of your population.

Slingshot Beginner Athletes to Better Push-Ups

It might be surprising that the first method I suggest is not a way to increase resistance, but a way to add assistance. A lot of coaches already use elastic bands to assist beginners or weaker athletes (push-up or pull-up variations are most common) when a movement is too difficult. In pull-ups/chin-ups specifically, while the bands add a boost, they don’t conform to a strength curve of the upper body.

We tend to use “eccentric only” methods, such as lowering push-ups or jump up and lower slow pull-ups (a great method is a reachable pull-up bar closer to the ground, as opposed to climbing up a full squat rack) to engrain the patterns and develop some much-needed strength in these beginner athletes. The push-up, on the contrary, is perfectly set up for “band assistance.” For more than three years now, we’ve been using the Sling Shot, a giant elastic band with arm holes. We find it’s the best tool for assisting push-ups (and bench press) and we have over a dozen of them at the facility.

Getting youth or weaker athletes better at the basics is too valuable not to mention; however, I think everyone can benefit from using the Sling Shot with their athletes or general population clients. Whether you are unloading the deep range of motion during a bench press, helping with lockouts during a strength phase, or adding a slight modification to an adult’s program, the Sling Shot is an inexpensive, invaluable, and remarkably easy tool to use. In addition to the variable or accommodating resistance that the Sling Shot provides, it also acts to “cue” athletes and engrain a better bar path and elbow positioning during the bench press (and push-up).

Video 1. Push-ups with the Sling Shot allow for full range work without removing entry-level plank benefits. It doesn’t matter if it’s rehabilitation or early strength training, Sling Shot bands are great tools.

I’m sure you’ve seen an athlete who undoubtedly flares their elbows as soon as the weight gets appreciable. The Slingshot encourages them to keep their elbows tighter during the press. You must use caution and coaching experience to understand the difference between tight and “too close,” but it provides some biofeedback instantly.

Potentiate with Chains for Jump Complexes

Most coaches will agree that complexes—exercises paired together—are for advanced athletes. It’s hard to say when an athlete is truly ready for complex training, but it’s easy to draw conclusions with potentiation, exercise proficiency, and conditioning demands. First, if an athlete has not polished the exercises individually, linking them together is just negligent. I’d argue that we see too many videos of young or inexperienced athletes being rushed into complexes, and the technique is poor and gets worse with fatigue.

Second, an athlete has to be in shape to handle back-to-back exercises; later in the off-season probably makes the most sense as the time to implement complex training. Nearly every coach is aware that potentiation works best for those with a great strength background, and while you don’t need to squat twice your bodyweight to take advantage of potentiation, you can’t use it with those new to the weight room or you will just drive the athlete into deep fatigue or fail to make appropriate gains.

Video 2. If you can’t do the exercises with polished technique in isolation, pairing them isn’t a good idea. Squats followed by jump exercises is a popular combination, but only for an advanced athlete.

One of the more important factors when using bands or chains is the precision required when choosing load. Without fairly strict loading parameters, the benefits may just be theoretical. While it’s often assumed that “toys” always provide a benefit, it’s not true, and potentiation works the same way. The science and research are heavily in favor of the responses from potentiation, but studies don’t always mimic training. Studies often cite using one or two exercises for two days a week for six weeks.

The precision required when choosing load is a critical factor in the use of bands or chains, says @ShaneDavs. Share on XYes, the response to the stimulus is impressive and appreciable, but modern training programs are typically much more complex than that. Most off-season programs must incorporate everything from speed, power, and strength to endurance and skill development in order to prepare the athlete. Depending on the frequency of an athlete’s training during their sport preparation, coaches might be forced to incorporate a multi-focused approach even within the same training session.

Properly placed complexes, however, do create a PAP affect, and if you use them with conditioned and advanced athletes, you will likely get a favorable response. Pairing jumps after band or chain work is extremely efficient and works great either in direct sequence (back-to-back or contrast sets) or after a potentiation-laced warm-up.

Save Time in the Weight Room with Bands and Chains

While the earlier point about potentiation benefits of great output and greater neurological adaptations have merit, the time-saving benefits of using bands and chains are more interesting if contrasted immediately and the forces are impressive. The term “biological load” sounds fancy, but barbell load is a little oversimplified. It’s hard to say how to calculate work with bands and chains because the total load on a bar is not the same as the interaction of the bar on a human body. High-quality work with all-out effort means athletes can reduce set numbers, but you have to increase the total work done and do it in a way that is purposeful. Decreasing one set of squats isn’t a huge change, but when paired with another exercise, you can get a lot of work done quickly.

Contrasting can be done with bands or chains, and with isometric actions, so plenty of options exist for coaches who want to challenge athletes but need scientifically sound approaches. Chains and bands are not isometrics, but a few pauses at different ranges with load can help save time by removing the need to do additional exercises. Bands have been shared with split squats in the Bulgarian article, but there’s no reason that a composite style of lifting sets can’t be done with isometrics and accommodating resistance methods.

Video 3. If an athlete doesn’t have a lot of time, heavy bands can make a difference, as they can be programmed to make every repetition count. The athlete can do a simple 3×5 program quickly when bands are set up properly.

A combined program of traditional and “special” approaches does get to the goal faster, as the results are better than one method alone. Sometimes a program needs to avoid bands and chains because of unique injuries or use bands and chains more often because of uncommon needs. Either way, the more methodologies used, the more likely a coach will find the right balance or more personalized technique for improvement than using only one modality. In no way am I suggesting that if you don’t use variable resistance methods you are missing out, but the rates of improvement are so strongly supported by the research they’re worth employing.

Perform Advanced Eccentrics with Band Benching

Eccentric overload is very tricky when using bands and chains for bench press. Technically, overload happens when the weight is beyond what can be pushed concentrically, so with heavy weights known to cause pec tears with NFL linemen and strong guys in general, what can be said about band benching and added speed? We know empirically that bench press injuries usually result from improper load selection, rushed progression, or poor technique of the lifter.

If they have not done enough accumulation over the past few months, a strong and talented athlete (especially after a prolonged break) could find themselves at risk for an upper extremity injury. So why bother with any speed or eccentric-style lifting at all? General eccentric overload is taxing, and adding a component of speed can be frightening at first. However, with proper adaptation, it should be a tool used more often for more seasoned athletes.

Athletes need to be exposed to reasonable risk in a systematic or intelligent fashion, not sheltered from harm. Reducing injury rates on the field isn’t about increasing the risk of injury in training; it’s about removing unnecessary or foolish risk. Pec, biceps, and triceps tears are collision-type injuries and are common in the NFL. They usually happen at end range and, like many injuries, most likely occur when the eccentric stress is too great.

The purpose of band benching is coordination of #eccentricoverload and reinforcement of game needs, says @ShaneDavs. Share on XIf a coach does not provide training that addresses tendon and muscle durability, then some responsibility must be taken by a coach who is willing to address the need. The increased eccentric speed that the band provides will help the athletes get more efficient at handling and reducing that stress at end range. Secondly, larger athletes with high velocities have higher momentum, so it’s up to those in collision sports to recognize that the upper body is another area that must be trained with care. Band benching isn’t the Nordic hamstring exercise of the upper body, but it’s a great way to challenge extensors of the elbow and shoulder.

Video 4. The correct band setup will add more speed eccentrically than normal lowering speeds, so be careful. Moderate loading with bands is aggressive enough to challenge athletes, but conservative enough that it doesn’t add unnecessary risk.

The intention of band benching is not just overloading the triceps; it’s about coordination of eccentric overload and reinforcement of the needs of the game. Having a better bench or better qualities within a bench press may not directly transform to an athlete playing better, but it’s better to be skilled, strong, and durable than just practicing the game.

Build Rate of Force Development and Propulsive Strength

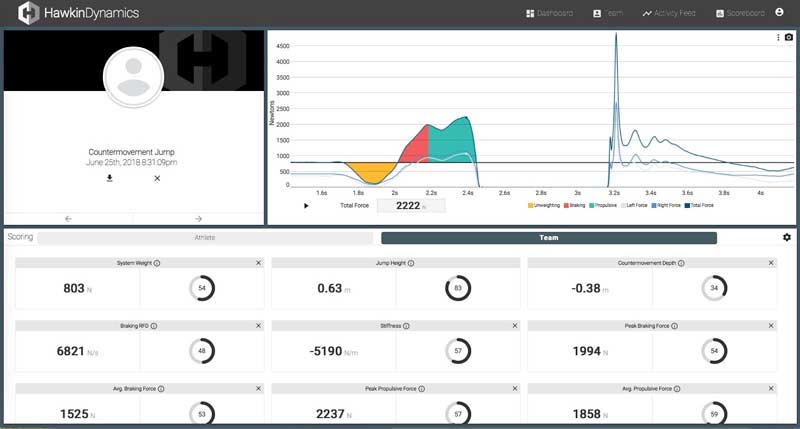

The use of variable resistance is like a two-for-one deal when developing the rate of force development (RFD) and propulsive strength of athletes. The first quality is more known, as RFD is common in strength and conditioning circles, but propulsion is still a mystery within the research. For example, many athletic motions at end range of extension may have very little or no impact because the follow-through has no real contribution to the speed of the exercise. Sprinting and throwing are prime examples, as the release and toe off may not add much to the equation, so it’s visually deceptive to coaches who don’t know the kinetics of the exercise. Force plates are a rare truth serum to the eyes because they remove what we intuitively believe is happening visually and measure how forces interact with a body.

So, if full-range strength is not as important to success with high-velocity movements, why focus on overloading that range of motion? Here is the paradox: Good weight training may be poor in specificity, but rich in program value. Constantly trying to reenact sport in the weight room is easy and will earn lots of social media attention, but the compromise in speed and overload is a waste of time and energy.

Good weight training may be poor in specificity, but rich in overall program value, says @ShaneDavs. Share on XPlyometric jumps and Olympic weightlifting may not always transfer to faster sprinting, throwing, or decelerating, but they may help keep athletes progressing when more specificity doesn’t reap a return. Coaches have theorized for years about the value of generating more work with less wear and tear to challenge the nervous system, and specific variable resistance may be the right fit for larger athletes who simply don’t respond well to on-the-field jump and sprint training.

Propulsive strength is a bit of a misnomer, as it may not help propulsion with sprinting for all athletes, but it covers the period of time where athletes tend to slow down and put the brakes on at the end of the lifting motion. You’ve probably seen an athlete who has either been coached to or just assumes that they must finish the squat or bench with speed, and they end up leaving the ground or locking out awkwardly and lose all the tension we seek so stringently. This is a poor decision, as we know the end range (top) of the movement is the least difficult and least influential on the force/propulsion we are after, so they should be coached to avoid this.

More skilled athletes find a way to finish properly, but there are some exceptions where bands and chains might help reinforce this concept. Taller athletes, such as basketball players, for example, tend to struggle due to their poor mechanical structure and lack of experience using the big lifts. Not only does variable resistance challenge the stronger athletes to increase their rate of force development, it allows the less strong and less technical athletes to push further into the movement without losing their tension and finishing the lift poorly. Any level of athlete can use variable resistance when the need is real, but advanced athletes tend to respond to bands and chains best because they’ve likely already run through the gamut of classic training methods.

Simulate Isokinetic Resistance Without Machines

I have almost zero experience with isokinetic machines or the motorized/pneumatic resistance that is more known today. However, there is some research that points to its relevance, especially regarding rehab or return-to-play protocols. No researcher in their right mind will tell you bands or chains are the same as isokinetic machines, but some similarities exist with movement velocity and during single or multi-joint machines.

Load changes, specifically increases in weight or resistance, will then, in turn, greatly reduce bar velocity. Although barbell speed is not completely uniform, the velocity is rather flat with minimal surges or spikes when using bands or chains. The main reason for the disappearance of these machines is probably due to their limitations beyond single joint actions. Bands and chains can somewhat remedy this.

Video 5. Isokinetic alternatives are a welcome find for athletes who need overload and quick improvements in strength when injured. Here, the concentric and eccentric speeds are rather uniform, simulating a lot of the benefits of isokinetics.

Isokinetic resistance has value, but what we see in rehabilitation and return-to-play programs is most notable. It is safe to get an athlete on their feet and use resistance that is similar to isokinetics because the athlete is loading slowly and steadily. While rapid and explosive movements are necessary for complete return-to-play status, some athletes are not ready for rapid actions.

This method of training—isokinetic simulation—isn’t really about mimicking actual benefits of the resistance mode, but replicating the performance benefits of the training for rehabilitation. Rehabilitation has nearly the same needs as performance, just scaled down and with some tricky caveats due to injury. Reducing velocity while increasing load with the right setup is very useful for rehabbing athletes, as joints are sometimes more tolerant of slow force loading than rapid contractions.

Periodize Programs Better with Partial Movements

The most straightforward way to change training is to change the range of motion. The research supports using mixed methods, or incorporating partials and full range training. It’s not sexy, but it works, and partial ranges of motion near full extension are actually great for breaking plateaus or sustaining gains in strength and power.

Quarter squats, rack pulls, and bench press partials are excellent options, but other supportive exercises are also useful provided the total stress is greater or equal than that of bands or chains. Partials with low resistance loads just spin the wheels of athletes, as resistance totals must be high enough (read: massive) because the work distance is incredibly short. For example, sprinting at high velocity has very low work distance to the hip and knee, but the overall work totals are high because the amount of power per step.

Video 6. Partial range of motion with squats requires a lot of careful setup so the first and last inches are demanding. You should include full range of motion squatting during the season and early in the athlete’s development.

Some coaches feel that the gap between isometric holds and slow concentrics gets into the grey area too much because heavy band resistance sometimes turns lockout speed into a grinding endeavor. As the load velocity hits near stoppage, the risk is dangerous with some movements, but this should never be an issue with partials if safety measures are in place. You don’t need to hit failure at all with partials, but due to the highly precise calculations required to get the most out of the shorter range, many coaches only benefit from the variation of the loading style, not the adaptations to the overload.

Make Variable and Accommodating Resistance Work for You

Overall, the key to using bands and chains is knowing when and where to fit them in and how to monitor changes. A big issue with bands and chains is that they don’t perform overload eccentrically closer to the ground or at the beginning of the barbell motion. Also, those using bands or chains for free weight exercises must consider the limitations of elastic resistance and linear resistance, as they are not supramaximally eccentric or isoinertial. Bands and chains cover a lot of needs, but they don’t do everything.

The key to using bands & chains is knowing when and where to fit them in and how to monitor changes, says @ShaneDavs. Share on XDeciding on using bands and chains, or other types of accommodating resistance, isn’t joining a cult—it’s just using the right tool at the right time. Several coaches see chains or bands as powerlifting tools, and we need to move on from that mindset and think about using specific development methods in strength as a complement to weightlifting exercises such as the clean and snatch.

Some users of bands and chains may see variable resistance as a solution to power training, while others tap into the technique only on special occasions. Either way, use bands and chains intelligently, not because they look advanced to other coaches or they impress athletes. Athletes do get excited by additional tools in the weight room because they crave variety, but only include them when warranted, as you can make plenty of progress by just polishing up the basics.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

As a young coach , one of the most detailed article on accommodating and variable resistance. Lot a free info that you would normally have to pay for or learn on your own .