Explosive weight training movements have become a mainstay in training serious athletes, especially those at the high school and college level. Note that I said weight training and not weightlifting.

Let me be clear. When I say weightlifting, I’m referring to the snatch and the clean and jerk—lifts performed in the Olympic Games. Not power cleans, hang power cleans, snatch pulls, one-arm snatches, and so on. Yes, competitive weightlifters often include such auxiliary exercises in their workouts (well, except for one-arm snatches—those are pretty worthless). Still, the core exercises in their programs are the snatch and the clean and jerk.

A research study about how the power clean affects sprinting or jumping ability is not a study about weightlifting. Share on XNext, consider that much of the North American research about weightlifting does not involve the full lifts but rather partial variations, primarily the power clean. A research study about how the power clean affects sprinting or jumping ability is not a study about weightlifting. It’s about an inferior variation of one of the two weightlifting exercises; in this case, the clean and jerk. These studies are certainly better than nothing, but not by much, for determining the true value of weightlifting for improving sports performance and preventing injuries.

Video 1. Christian Rivera, an athlete coached by the author, shows the explosive nature of weightlifting. During his third lift, note how Christian’s training and athleticism enabled him to save an out-of-position snatch that was 85 pounds above bodyweight. (Video by Lifting.Life)

Yes, many strength coaches and personal trainers take seminars that cover weightlifting, and among the most popular are those sponsored by USA Weightlifting. A good start, but few coaches take their weightlifting education to the next level by practicing the full lifts, even fewer compete in weightlifting meets, and most prefer to have their athletes perform partial variations.

Many myths about true weightlifting have come from limited hands-on experience coaching the snatch and the clean and jerk. Share on XThis limited hands-on experience and the lack of coaching the lifts are responsible for many myths circulating about real weightlifting. Here are eight of them.

Myth #1: Partial Weightlifting Movements Are Easier on the Knees

I started competitive weightlifting in 1972 after reading about the sport in Strength and Health magazine. It was a time when many health care professionals condemned squats. The most notable opponents were Professor Karl K. Klein and Dr. Fred L. Allman, authors of the controversial book published in 1969, The Knee in Sports.

If an athlete insisted on doing squats, these doctors said they should only perform them through a partial range of motion. Klein and Allman argued that squats—specifically full squats—could cause permanent lower body instability (by stretching the knee ligaments) and, as such, increase the risk of serious injury. They were wrong.

The highest amount of harmful knee stresses during squats occurs with the thighs at or above 90 degrees, not full squats (hamstrings to calves). Share on XThe highest amount of harmful stresses on the knee during squats occurs with the thighs at or above 90 degrees, not full squats, meaning hamstrings touching the calves. Wimpy exercises such as the hang power clean (which starts and finishes with the legs in a quarter-squat position) are not knee-friendly. What’s more, the finished position is horrific because the athlete jams their knees when they abruptly catch the loaded, rapidly moving barbell. Let me take this discussion a step further.

Surgeons have often found that during ACL surgery, the ligament(s) they repaired already showed signs of chronic damage. This means many ACL tears were not a result of a single “supramaximal force” but from cumulative trauma caused by “submaximal forces” that predisposed this ligament to debilitating injury. Like an old rubber band that is frayed and stiff, these ligaments were ready to snap. Incidentally, the recommendations by the authors of one paper on this subject were to limit the number of jumps young athletes performed during training, such as the Little League “pitch count” that limits how many pitches a young baseball player can throw in a game.

Although advances have been made in ACL reconstruction that let many athletes to return to their previous levels, why subject an athlete to such harmful stress in the first place with quarter-squat movements? This advice would be especially wise for female athletes because—depending on the sport—they can be up to 5x more likely to injure this important ligament.

Myth #2: During the Pull, the Feet Should Be Flat on the Floor Until the Knees Fully Extend

The common technique taught in many strength coaching courses is to stay flat-footed during cleans and snatches until the knees fully extend—the so-called “triple extension.” Such advice belongs in the Iron Game history books.

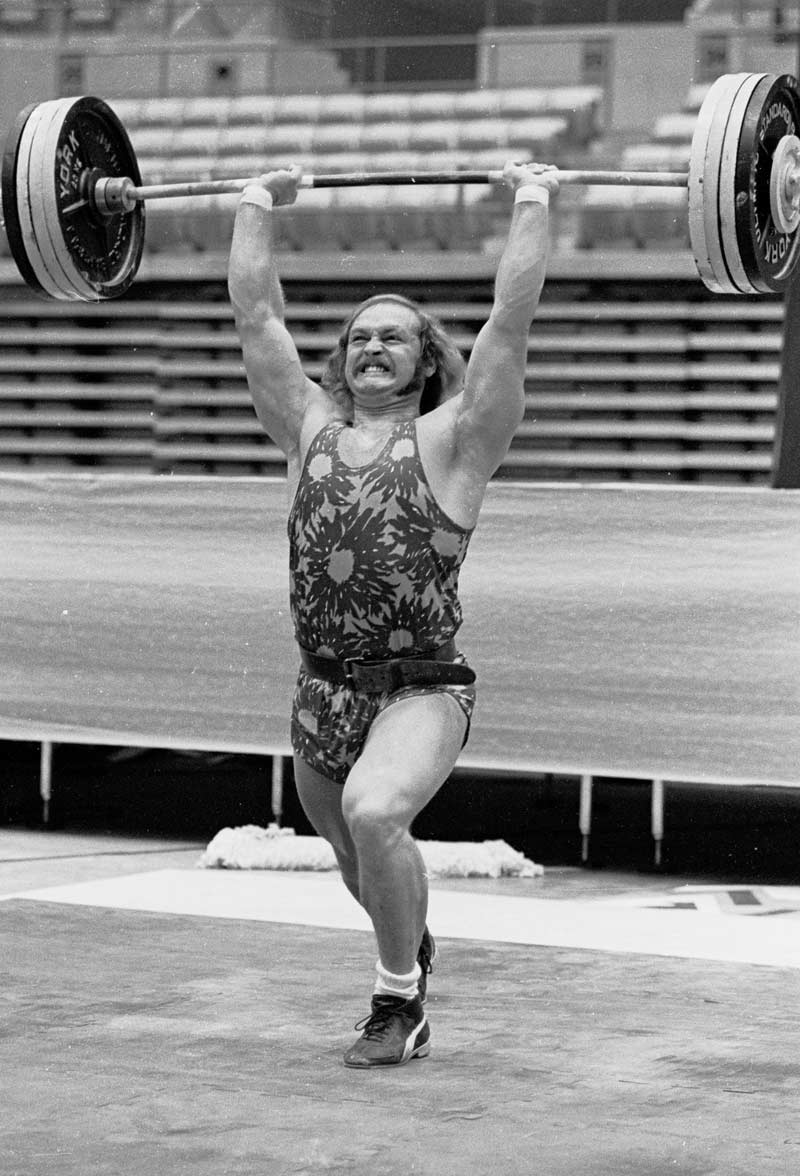

In Russian weightlifting textbooks from the 1970s, coaches promoted staying flat-footed before achieving full knee extension. That was then—this is now. If you study slow-motion video or sequence photos, you’ll see that many of today’s elite lifters perform plantar flexion (i.e., lifting the heels) well before their legs straighten. Doing the triple extension during a weightlifting exercise is equivalent to today’s high jumpers performing the scissor-type jump rather than the Fosbury Flop—it works, but it’s inefficient.

Elite athletes lift their heels before the knees are completely straight, using the Achilles tendon to increase force production dramatically. Share on XMany strength coaches argue that sports involve triple extension, and therefore we should practice this method in weightlifting. Ah, no. Watch jumping movements by elite athletes in sports, and you’ll see their heels will rise before the knees are completely straight, enabling them to make better use of the Achilles tendon as a biological spring. In effect, they use this powerful tendon to dramatically increase force production, much more than the make-believe triple extension concept.

It follows that performing hang or block movements are also less effective for power production than performing lifts from the floor. I say this because, in every video, article, and book I’ve seen describing how to perform hang cleans and hang snatches, these lifts start with the entire foot on the floor. Further, you often see many non-weightlifting coaches teach these partial variations so the barbell doesn’t move directly upward. Instead, the bar’s initial movement is diagonal, looping back around before violently slamming back into the athlete’s shoulders. Ouch!

Myth #3: The Shoulders Should Move in Front of the Knees During the Pull

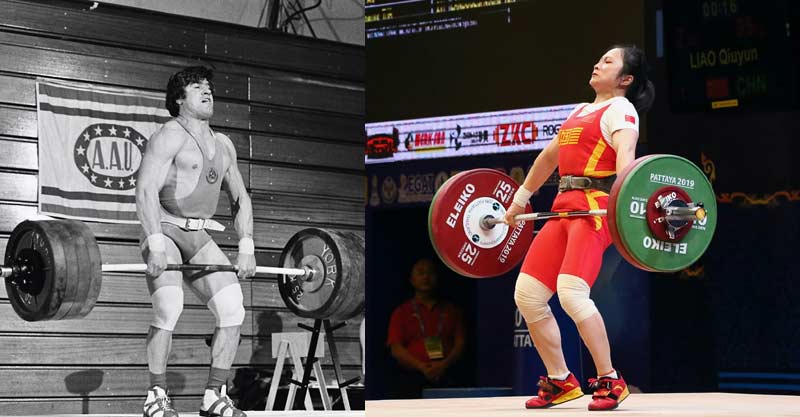

Many strength coaches incorrectly teach weightlifting as a jump. They tell their athletes to extend their shoulders far in front of the bar when it passes the knees and then move to a vertical posture and “jump.” Weightlifting scientist Bud Charniga has done extensive research on the training methods of successful Chinese women lifters and says they found a better way.

Chinese coaches have enjoyed tremendous success by having their female athletes start with the shoulders directly on top of the barbell and then pull their shoulders behind the bar after it reaches knee level. This technique reduces the stress on the lower back (a weak link in the Russian method) and positions the bar closer to the center of mass, where athletes can apply more force to the barbell. It also increases the torso’s range of motion, enabling the athletes to use their upper body more effectively to move under the bar faster. If an athlete can move under the bar more quickly, the bar doesn’t have to be pulled as high. And the lower you have to pull the bar, the more weight you can lift.

Some male athletes can reach an elite level using the shoulders-in-front technique, but those who do often need to spend additional time with special exercises to strengthen the lower back. If you study their weightlifting textbooks, you’ll see that Russian weightlifting coaches frequently prescribed exercises like back extensions and good mornings for their athletes in the ’60s and ’70s. These exercises were essential because their pulling technique put excessive and prolonged stress on the lower back.

Video 2. Elastic strength enables athletes to produce more powerful movements than muscle strength alone. Here Christian clean and jerks double bodyweight, a New England record. This is followed by a clip showing that his shoulders don’t extend over the bar at any point in the lift.

Myth #4: The Powerlifts Generate More Power than the Olympic Lifts

Athletic movements are characterized by fast eccentric (muscle lengthening) contractions. You would see such actions when a quarterback cocks their arm back to throw a pass or when a weightlifter dips for a jerk.

Strength coach and posturologist Paul Gagné and his colleagues have conducted considerable research on what he calls Velocity Eccentric Overload (VEO) training using flywheel devices that increase the eccentric load at high speeds. Gagné says fast, powerful eccentric movements enable athletes to use the elastic qualities of the connective tissues to produce higher levels of power. Take sprinting, for example.

Sprint speed is not only determined by stride length and stride frequency but also ground contact time. One of the qualities that set Usain Bolt apart from his competitors was that he spent so little time on the ground compared to his competitors. You’re not going to achieve these benefits by performing slow, partial-range powerlifting exercises.

Myth #5: Weightlifting Doesn’t Develop Rotational Strength

I see many workouts for baseball players and other athletes in throwing sports that involve performing horizontal twisting exercises with bands and cables. The idea is to focus on the obliques to develop rotational strength and power. Nice try.

Gagné says the problem with this approach is that few muscle fibers in these core muscles are transverse (aligned horizontally) to the trunk. Instead, most are arranged in a diagonal pattern more suited for producing positive torsion, which is rotation coupled with flexion, such as the downswing in golf.

“Consider the biceps, which has fibers arranged longitudinally,” says Gagné. “You would not work the biceps by pulling your arm across your body because the fibers are not arranged this way. Also, because rotating the spine on a single axis is not a natural movement pattern, and this type of activity, especially when performed seated, creates large shearing forces on the spine that can easily damage the disks.”

There is also the issue of counter-rotation.

“J. P. Roll, the founder of Posturology, found that what occurs to one side of the body will help neurologically ‘code’ what can happen on the other side,” says Gagné. “As such, the ability to rotate in one direction is influenced by how well that individual can create rotation in the opposite direction—this is called ‘counter-rotation.’ In other words, the body will only allow for a certain amount of disproportionate development of the muscles. In working with professional golfers, for example, we found we can increase the ability of a right-handed golfer to generate club speed by having them work with a left-handed club.”

What type of weight training exercises strengthen counter-rotation?

“The late Mel Siff told me about research showing that the snatch is the best way to work on rotation, because to perform it you need a lot of counter-rotation,” says Gagné. “An overhead squat, performed as weightlifters do them, involves a lot of counter-rotation to maintain proper alignment.”

Hmmm…maybe this explains why so many elite discus throwers and shot putters perform weightlifting exercises in their workouts.

Myth #6: Weightlifting Exercises Should Be Performed with Submaximal Weights

Apparently, it’s fine for strength coaches to overload all areas of the strength curve of squats and bench presses with chains and bands because, as they say, “All things being equal, the strongest athlete always wins!” But when it comes to weightlifting, many strength coaches seem to believe that light weights rule. This trend appears to be especially evident with many sprint coaches.

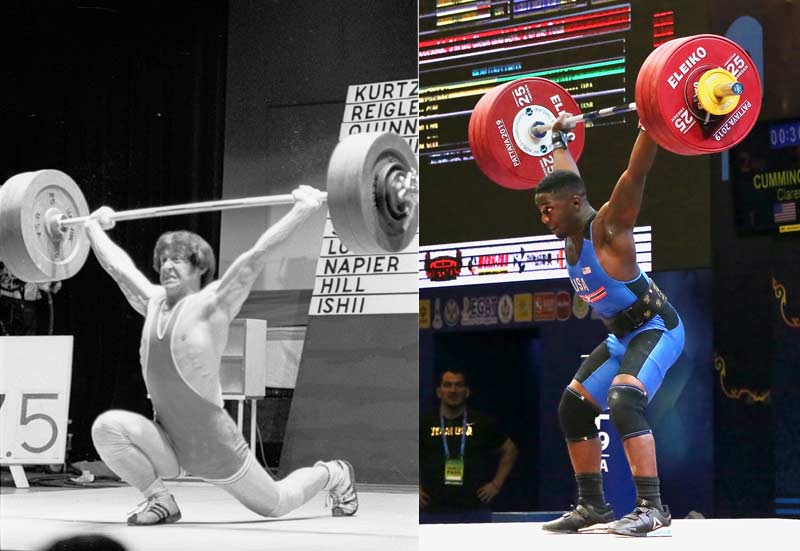

When sprint coaches recommend weightlifting exercises or their variations, I often see workouts focusing on weights that represent about 70 percent of an athlete’s one-repetition maximum. The exercises also are performed for relatively high reps, such as power cleans for sets of five. For example, Bolt can be seen on YouTube doing sloppy hang power cleans for a set of 10 reps with what appears to be between 115 to 135 pounds. His time would be better spent taking a Zumba class. Seriously, my point is that many other sprinters often run super fast despite their weight training workouts, not because of them. By the way, several Chinese female lifters have clean and jerked 2.5x their bodyweight, and a half dozen male lifters have done 3x their bodyweight.

Many sprinters often run super fast despite their weight training workouts, not because of them. Share on XLight weights may not add muscle mass, which is important. Too much bodyweight, even if it’s muscle, will adversely affect speed because it’s more weight to move—wear a 20-pound weight vest and see what happens to your 40-time. That said, light weights for high reps will do little to develop power because they will not train the powerful, fast twitch muscle fibers. In fact, when I look at many of the published workouts of Russian sports scientists about training programs, often lifts of 70 percent and below are not listed, as these are considered warm-ups and don’t contribute to the training effect.

Light weights for high reps will do little to develop power because they will not train the powerful, fast twitch muscle fibers. Share on XBy focusing on heavier weights, such as 85-100 percent for sets of 1-3 reps, you can develop more powerful muscles with minimal increases in bodyweight (i.e., relative strength). Weightlifters often train for several years and become considerably stronger without adding any additional bodyweight. Further, bodybuilding methods can adversely affect a muscle’s ability to produce high levels of muscle tension quickly.

There also seems to be a prevailing idea among many sprint coaches that it’s possible to reach the highest levels in the sport without ever touching a barbell. Yes, it’s true—sprinters need to sprint. Likewise, baseball players need to throw and hit baseballs, basketball players need to dribble and shoot baskets, and golfers need to hit golf balls and wear ugly pants.

The reason so many athletes don't get much benefit from explosive exercises is that their workouts are designed poorly. Share on XOn this subject, I highly recommend Dr. Harold Klawans’ book, Why Michael Couldn’t Hit. My point is that the reason so many athletes don’t get much benefit from explosive exercises is that their workouts are poorly designed.

Myth #7: Weightlifting Workouts Should Be the Same for Men and Women

Although this is the subject of a more extensive article, the physiology of women is such that they need more warm-up sets to reach maximum results in weightlifting, and they can handle more sets at higher intensities than men. Yes, it’s much easier for a strength coach to have everyone follow the same workouts, but it’s not the most effective way to train female athletes.

Myth #8: Weightlifting Exercises Are Too Difficult to Teach

Many coaches believe the Olympic lifts performed from the floor are too difficult to teach. I guess if we can’t teach a weightlifting exercise in five minutes or less, it’s not worth learning? If this is the case, why practice any sport? Hitting a 90-mile fastball seems like a pretty hard skill to teach, as is sinking a three-point shot and performing a triple axel.

If an athlete does not have the flexibility to do a squat clean, consider that you just identified a mobility problem that may affect athletic performance and increase the risk of injury. Rather than working around the issue with inferior exercises, consider that practicing the lifts, even with light weights, often quickly fixes the problem. And consider that lack of mobility to perform weightlifting exercises is mainly a problem with male athletes—it’s rare to find a woman who can’t achieve the full squat clean position the first time they try.

Certainly, performing a full squat snatch can be difficult for many athletes, and the jerk is even more difficult. However, it’s not that hard to teach a full clean or a push jerk. For those with extreme mobility issues caused by chronic injuries (or just because that’s the way they are), there is the option of the split-style of snatching and cleaning. I would also caution that if a coach is going to teach full lifts, they must have the athlete practice missing the lifts to avoid becoming a highlight for a “Weight Training Fail” video on YouTube.

If a coach is new to lifting, rather than just taking a course, they should try to recruit a weightlifting coach to help them with their teaching. At the very least, call a local weightlifting coach (USA Weightlifting has a directory of clubs nearest you) and ask to sit in on a few training sessions and ask questions. I’ve been in this sport since the ’70s, and I’ve never heard of a weightlifting coach turning down a strength coach or sports coach’s request to stop by and watch their athletes train and ask questions.

Weightlifting and Athletic Fitness

As a weightlifting coach and a former weightlifter, I certainly have a vested interest in dispelling myths about the sport and promoting the snatch and the clean and jerk for athletic fitness. After all, weightlifting is the greatest sport in the world! That doesn’t change the fact that the snatch and the clean and jerk are valuable exercises that can help athletes achieve physical superiority and reduce their risk of injury.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

Terry, T. “Historical Opinion: Karl Klein and the Squat.” Strength & Conditioning Journal, 1984; 6(3): 26-31.

Hartmann H, Wirth K, Klusemann M. “Analysis of the Load On the Knee Joint and Vertebral Column With Changes in Squatting Depth and Weight Load.” Sports Med, 2013; 43(10): 993-1008.

Junjie Chen, et al. “An Anterior Cruciate Ligament Failure Mechanism.” The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 2019; 47 (9): 2067-2076.

Charniga, A. “Can There Be Such a Thing as an Asian Pull?” EWF Scientific Magazine, 2016; 2(4): 24-32.

Goss, K. What Sprinters Must Know About Elastic Strength.

Meijer, J.P., et al. “Single Muscle Fibre Contractile Properties Differ Between Body‐Builders, Power Athletes and Control Subjects.” Experimental Physiology, 2015; 100(11): 1331-1341.

Klawans, H. Why Michael Couldn’t Hit: And Other Tales of the Neurology of Sports, pp 10-53, W.H. Freeman & Company, 1996.

Charniga, A. “Comparison of Warm Up Protocols of High Class Male and Female Weightlifters.” EWF Scientific Magazine, 2015; 1(1): 56-71.