Paul Caldbeck, MSC, ASCC, CSCS, is currently a consultant performance coach, and doctoral candidate at Liverpool John Moores University, where his research centers on contextual sprinting in soccer. He previously held the position of Physical Preparation Lead at a Premier League soccer club. Caldbeck has extensive experience in strength and conditioning and sport science across a range of sports.

Freelap USA: Contextual sprinting is important for coaches in sports such as soccer, lacrosse, American football, and rugby. Can you explain how to get started analyzing a sport beyond passing the eyeball test? How does one break down the small events during a game to summarize the patterns of the sport better?

Paul Caldbeck: Sprinting occurs during the most crucial moments of field-based team sports. This is typically as a result of an offensive player seeking separation from a defensive counterpart and vice versa, a defensive player attempting to maintain distance. These efforts often determine the eventual outcome of the match, and, ultimately, effectiveness in these key moments is how a player will be judged.

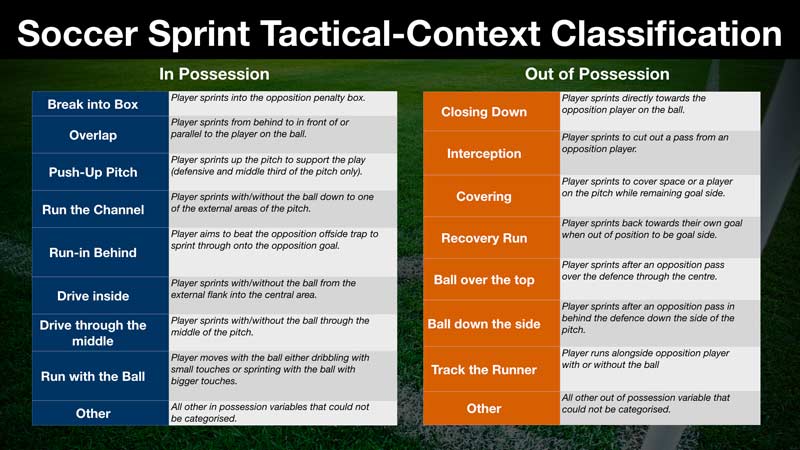

While these sports are obviously chaotic in nature, we can attempt to reduce match activities into key, defining contexts. Such a classification system has been previously developed in soccer (Table 1)1 and can easily be completed in similar sports through a systematic process of categorizing phases of play and specific actions during a match.

For my own doctoral research into contextual sprinting in soccer, I developed two systems. The first sought to quantify “how” sprinting in soccer was completed, focusing on the types of movement that made these efforts “soccer-specific.” Typically, as performance practitioners, we assume sprinting during a match is different than during track and field, but little data existed to back this up. Thus, the first stage of my thesis aimed to establish whether these differences actually existed and how pronounced they were. By better understanding the movements associated with the key moments (sprinting) during a soccer match, we can look to direct our programming toward what matters most.

However, it is obviously the case that any movement that presents itself during a match is a direct result of the match itself, and the athletes’ perception of the match. Therefore, the second system we developed—the Soccer Sprint Tactical-Context Classification System—aimed to quantify “why” sprinting occurred during soccer, and we created it from previous work in the area. We can then implement this type of system and produce profiles for specific positions, allowing us to develop our performance programs specifically relating to these key moments of a match.

Unfortunately, there is currently no automated means of attaining this data, to my knowledge, so it is a case of old school video analysis! Getting a reasonable sample size for one athlete can take a couple of hours. But once we have this data, it is absolute gold dust for performance coaches. In Premier League soccer, a player may sprint around 20-40 times during a match. If we can even slightly enhance their effectiveness in one of these efforts, then we can potentially have a direct influence on match outcome.

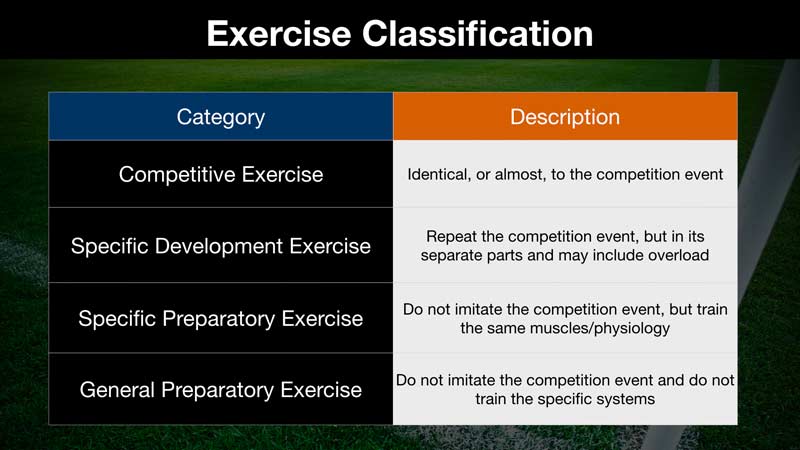

Using this context information, and by thinking of all physical training on a spectrum from specific to general, we can begin to design a holistic program to directly influence on-field performance by “reverse engineering” these contexts. I am a big fan of work by the likes of Shawn Myszka, where we facilitate the learning of the athlete through exposure to specific contexts and “repetition without repetition.”2

So, our first stage would be to expose the athlete to these sprinting contexts in practice. If, for example, a soccer center back repeatedly sprints due to a ball down the side of the defense, then we start by designing drills that replicate this scenario and manipulate the constraints (organismic, task, or environment). These may be different positions in the defensive line, different numbers of offensive players, or a different pitch location, for example. This allows the athlete to truly develop the coupling between perception and action through means such as enhanced pattern recognition.

The next stage in the process would be to begin to isolate the specific skills involved in these contexts. So, in the above example of a center back facing a ball down the side, they will likely complete a lot of sprints from a rear initiation position, which involves a drop step movement. Again, we can create drills to isolate this action; we can easily incorporate them into warm-ups.

This allows us to begin to overload the specific force demands of the actions by completing them with maximal effort and focusing on technical efficiency. The learning is again achieved through the athletes’ exploration of the constraints the drills place upon them, rather than rote learning of footwork drills. Certain drills may involve specific match-related stimuli, and at other times we sacrifice this for more specific training.

Beyond this stage of the spectrum, we begin to forego specificity for the ability to overload the physiology stressed in the activity. So, in this sprinting context, we may seek to develop power production and the ability to apply it in multiple directions. For example, we may first employ resisted sprinting and multidirectional power exercises. At a certain stage, we will favor overload completely over specificity and look at standard weightlifting or squat jumping—general power production methods. And finally, we have our most general physical development methods, such as strength training and any prehabilitation work the athlete may require.

We may employ each of these methods concurrently or as the focus of certain mesocycles. However, the broader point is that we always relate our performance enhancement program back toward the key contexts that can ultimately determine whether the team wins or loses, or the athlete is successful or unsuccessful.

I believe the key development for the future of performance training is better integration with match-related activities, says @caldbeck89. Share on XWhile I am a firm believer in the importance of general strength and power training, I believe the key development for the future of performance training is better integration with match-related activities. We shouldn’t be afraid to discuss sport-based movement with head coaches. I believe we sell ourselves short as an industry if we just concern ourselves with weight room numbers, and the likes of Shawn Myszka are really taking us to another level.

Freelap USA: What is a good way to assess curved sprinting? Many coaches time the speed of running in a circle, but should we look at right and left information or compare it to linear speed? Where are we going here with testing curved speed?

Paul Caldbeck: Depending on the method of measurement used and how we define curved sprinting, the majority of sprint efforts in field-based team sports will involve some degree of curvature. My own doctoral research observed 87% in soccer, across all positions. Here though, the problem lies with how we as performance scientists decide to reduce these efforts into defined categories such as curves and swerves, creating potential contradictions within the research. However, regardless of methodology employed, our athletes need to be effective at maintaining velocity, or accelerating, while traveling in a curvilinear motion, and at varying degrees.

Regardless of methodology employed, our athletes need to be effective at maintaining velocity, or accelerating, while traveling in a curvilinear motion, and at varying degrees. Share on XThe literature directly for team sports is scarce, but from research on track sprinters, we know there are biomechanical differences between curvilinear sprints and typical linear efforts. There are differences in force demands, such as the inside leg generating greater inward impulses and turning, and the outer leg producing greater anteroposterior demands compared to straight line sprinting. Obviously, these studies are completed on the standardized curve of an athletics track, whereas in team sports, these curves will frequently vary in distance and degree. But what is clear is that curved sprinting is a unique skill and if sprinting can determine match outcome, and most sprints will involve an amount of curvature, then this should be a key focus of any good performance program.

With regard to testing, the philosophical purpose of a testing battery is key to the selection of a test for curved sprinting. Are we attempting to truly test an athlete’s ability to sprint during a match, or relying on a general test of curved sprinting ability that may reflect an athlete’s potential ability during a match? Here many “combine style” testing batteries fall foul of Goodhart’s Law where, “when a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.” Research using the NFL Combine results has shown this method of testing is only a “modest” predictor of future performance. But, while being cognizant of these inherent flaws, we can still analyze an athlete’s broad capacity to run fast along a curve.

Recently, attempts have been made to ascertain average angles of sprinting in soccer using the tangent-chord method.3Here, the study concluded an average angle of 5 degrees but potentially as large as 30 degrees. So, a standardized testing procedure may involve the comparison of distance-matched (say 30 meters) linear, and 5-degree left and right curved sprints. A decrement value can then be ascertained for time to complete or maximum velocity attained, both for linear versus curved and left versus right.

For example, if an athlete can attain 10 ms-1in a 30-meter linear sprint, but only 9 ms-1 during a 5-degree, 30-meter sprint, we would get a curve decrement of 10%. This would then give us a general, broad understanding of an athlete’s curved sprinting ability. However, it is crucial to understand the limitations of such a method, such as the potential skill differences across a range of varying angles and how far removed this type of effort truly is from sprinting during a match.

While this method satisfies our scientific desire for test validity and reliability, nothing can match consistent observation of an athlete during competition. For me, that has to be our foundational assessment method. Controlled testing procedures should only ever support this, rather than be the principal driver of our programming.

Freelap USA: Many coaches argue that pure peak velocity needs to be used to sustain global output and raise the CNS ability, while some coaches only care about practicing. How do you get an athlete better while ensuring that actual transfer is occurring?

Paul Caldbeck: Naturally, the answer to most polarizing debates lies somewhere in the middle, and I certainly believe this when it comes to general versus specific methods. While I think it is important to be specific with a lot of our training, at times it is necessary to sacrifice this specificity for the opportunity to overload certain underlying capacities that are crucial for performance. For me, this is the case with sprinting as much as it is for general barbell strength training.

At times it is necessary to sacrifice specificity for the opportunity to overload certain underlying capacities that are crucial for performance, says @caldbeck89. Share on XMany contextual sprinting efforts completed in sport are inherently submaximal—Ian Jeffreys refers to these activities as “game speed”4—whereas maximum velocity capability for team sport athletes is a “capacity” quality. Obviously, an increased capacity gives an athlete the ability to achieve greater performance in these submaximal efforts: A 9 ms-1athlete is unlikely to be more effective at game speed movements than one who can achieve 10 ms-1. It is therefore crucial to still consider enhancements of maximum velocity, though the real question is, how much is enough!? At the elite level in team sports, maximum velocity likely becomes less of a determinant of performance and the ability to “exploit” this capacity during a match becomes the key.

However, sprinting at maximum velocity in a controlled practice environment should be a fundamental aspect of any team sport athlete’s physical development program. Not only does it “vaccinate” against potential hamstring injury, but the kinetic demands of maximal sprinting are also unparalleled. It is almost impossible to match this force application demand in such short time frames elsewhere in our programming.

Similarly, athletes should well understand the standard “rules” of good sprinting before they learn to break them during more sport-specific activities. Sprint coach Jonas Dodoo often references projection, reactivity, and switching as being fundamental to running fast; this is as true for team sport athletes as it is for track sprinters.

The issues arise, though, when the sole focus of our programming becomes improving an athlete’s 40 time. While, as noted, linear speed will always be important, we should not seek constant improvement at the expense of sport-specific sprinting skills. If an athlete is unable to effectively “spot the gap” faster than an opponent and utilize efficient movement skills to apply their velocity capacity, a 10th of a second faster 40 time is useless. A performance coach’s role is to decipher an individual’s performance limiter.

As an aside, the sport I have been involved with most is soccer, and I believe that coaches’ current focus on small-sided games in practice is likely a huge factor in the prevalence of hamstring injuries. From a very young age, athletes are constantly exposed to these reduced area drills, which work great at increasing technical exposure, but are likely developing ineffective movement skills when then placed into a match situation in a much larger area. Learning to run at high velocity over 30+ meters should be a fundamental aspect of a developing soccer player’s program. I can’t recommend highly enough the benefits of learning to sprint effectively at the local track club.

Freelap USA: Athletes who test well in all areas of performance still have to be skilled. How do you work with team coaches to determine where real deficits are? When does it become the responsibility of the sports coach and when does a fitness or performance coach need to step in?

Paul Caldbeck: Ultimately, the performance staff is there to support the sport coaches, and the direction and philosophy of the team is always their responsibility. With respect to performance, the determination of any deficit should consequently be a collaboration between sport coaches and performance staff. It’s crucial to understand that no sporting skill is performed during a match without an element of physical demand, and vice versa. Thus, an optimal program will always seek to fundamentally combine the two.

A direct line of communication between sport coaches and performance staff is fundamental to an organization’s success. While a head coach should have the ultimate say on the direction of an athlete’s programming, we as performance staff should, with our expertise, be a strong voice in these discussions. It is our responsibility to prove our worth to the coach.

After performance staff establishes key physical contexts through a classification system, these contexts allow us to talk in the coach’s own game-referenced languages, says @caldbeck89. Share on XAs discussed above, we can establish a quantification of the key physical contexts through a classification system. We can even weight these contexts for importance to match outcome and assess an athlete on their performance in these key moments, thus developing a needs analysis of potential performance deficits. Rather than discussing an athlete’s irrelevant 40 time or power clean 1RM, these contexts allow us to talk in the coach’s own game-referenced language. This can then increase buy-in from coaches and athletes and create a common language across the organization.

Freelap USA: How do we make practice better? A lot of strength and conditioning coaches get frustrated with team coaches, as they are usually left with very little time and energy to train outside of playing and practicing. What do you suggest for merging on-the-field work without resorting to a cliché warm-up of mini hurdles and cones? How do we get speed injected into training?

Paul Caldbeck: As discussed, the ultimate responsibility lies with the head coach, and performance staff is in place to support them. I don’t believe it is healthy to view our practice as competing for time with sport coaches, though I do understand this frustration. I believe a paradigm shift to reverse engineering from these key contexts to rationalize our interventions to coaches is the key to “selling” our demand for time. Rather than viewing training in silos as weight room time and sport time, all types of practice should be seen as training, and this shift is key to getting coaches on side. I feel this is often better achieved in track and field than team sports.

Rather than viewing training in silos as weight room time and sport time, see all types of practice as training. This shift is key to getting coaches on side, says @caldbeck89. Share on XWith the knowledge of the ultimate physically demanding context we seek to enhance, all facets of training can be skewed toward focusing on this. The messages from performance staff should always relate back to this context: it is the reason we lift, the reason we complete linear sprints during a warm-up, and the reason we do our post-practice yoga. With this in mind, performance staff should seek to influence aspects of daily practice; this is common in soccer.

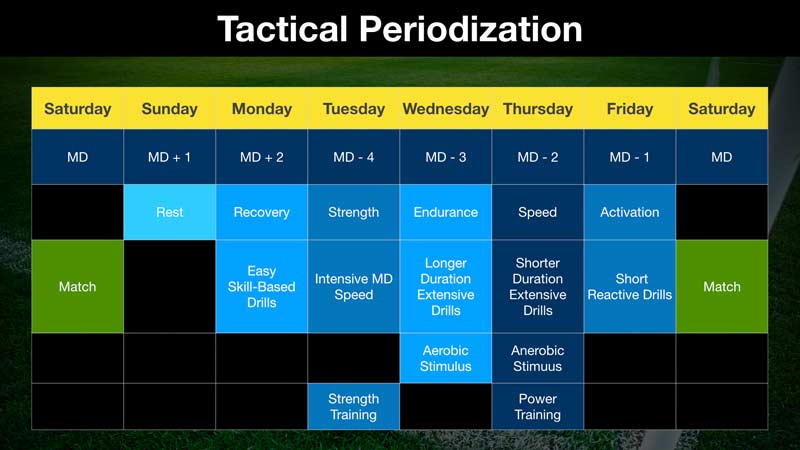

The head coach will typically discuss the theme for the day’s practice with the performance staff to ensure optimal physical development. They will hope to achieve the physical goals for the day/week within the broader macrocycle as much as possible within the regular practice.

For example, this “tactical periodization” approach may dictate that the day’s training theme is “intensive/multidirectional speed.” Practice drills will be selected to encourage regular intense changes of direction; this is typically achieved by reducing the space available in drills. Alongside this, weight room time may consist of high force activities, warm-ups may involve closed change of direction drills that reflect the key sprinting contexts, and the performance coach’s drill time may specifically mimic these intensive sprinting match contexts.

Training the specific key contexts should thus be incorporated into typical practice rather than competing for time. For example, in soccer, a coach may employ a “crossing and finishing” drill with the aim of practicing a player’s specific sport skills in these actions. They can easily manipulate to provide a movement skill acquisition and physical stimulus; thus, optimally combining perception and action. These drills then provide “repetition without repetition” and facilitate the athletes learning to apply their physical ability in a specific context through exploration.

As noted, game speed is about much more than pure physical capacity. By constraining the drill in different manners, we can alter the types of sprint efforts completed by the attacking player to suit their physical needs.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

1. Ade, J., Fitzpatrick, J., and Bradley, P.S. “High-intensity efforts in elite soccer matches and associated movement patterns, technical skills and tactical actions. Information for position-specific training drills.” Journal of Sports Sciences. 2016; 34 (24): 2205-2214.

2. Myszka, S. “Movement Skill Acquisition for American Football Using ‘Repetition Without Repetition’ to Enhance Movement Skill.” NSCA Coach. 2018; 5(4): 76-81.

3.Fitzpatrick, J.F., Linsley, A. and Musham, C. “Running the curve: A preliminary investigation into curved sprinting during football match-play.” Sport Performance and Science Reports. 2019; 55(1): 1-3.

4. Jeffreys, I., Huggins, S., and Davies, N. “Delivering a Gamespeed-Focused Speed and Agility Development Program in an English Premier League Soccer Academy.” Strength and Conditioning Journal. 2018; 40(3): 23-32

5. Delgado-Bordonau J.L. and Mendez-Villaneuva, A. “Tactical Periodization: Mourinho’s best-kept secret?” NCAA Soccer Journal. 2012; 6: 29-34.