[mashshare]

Experimenting with isoinertial training during the last year has led us to seven methods that are useful for coaches, and are not just new or different for Instagram. Changing everything you do every time you leave a seminar or buy a product is a sign of a poor system. Evolution, however, is a must. After a great summer, we found our flywheel training start to grow and advance as we’ve practiced and learned from others in our field.

We’ve created a simple continuum, from basic concepts to very advanced techniques that are not for everyone. If you’re interested in flywheel training, the information below is compelling, at the least. If you’re a coach in the right environment wanting to push the limits and depend on flywheels, this article will be valuable as well. Whatever the case, this review covers methods that span from the most basic fundamentals to the elite.

The Spectrum of Techniques

While we wanted to show incremental progressions of flywheel techniques, we realize no continuum is perfect. Ideally, each method moves in a linear fashion, so coaches can safely ramp up the demand on their athletes. The science of strength and conditioning is far from perfect, so there’s enough art left to give coaches plenty to play with.

Flywheels can be used by new trainees as well as the most elite athletes. It may seem that experimenting with elite and pro-level athletes is a huge risk, but if we’re going to make progress, we will continue to progress. There are times when unconventional and new is just what a top-level athlete needs to improve their performance.

The spectrum of flywheel techniques ranges from secondary strength exercises to accentuated eccentric overload, the most extreme form of strength training. This list is the first crack at ways to progress training methods, not just progressions of exercise. Down the road, I’m sure additional ideas will become part of this continuum, but for now, this is will make a dent in flywheel programming.

Below are the seven primary methods we’re using at our facility. We hope other coaches experiment with them and share their practices in the future.

Supplemental Ancillary Training

If you’re new to flywheel training and don’t want to take a leap of faith, this method is perfect. Take any basic secondary exercise, which is usually placed at the end of workouts because they’re important enough to include but not a priority, and use a flywheel option. Ancillary exercises let athletes experience flywheels without shocking their system. In our experience, it’s best to take time to become familiar with both the resistance of flywheels and the exercises themselves. Remember, most youth athletes are new to training properly, and basic exercises with flywheels are rather demanding, so be patient.

We have both the kPulley and the kBox and like to mix and match the training just enough to give our athletes enough exposure so they understand the concept of flywheels before we start advancing. Progressing slowly leads to the fastest changes and adaptations by letting you avoid having to take a few steps back from errors or miscalculations. Slow and steady wins the race.

[vimeo 381059855 w=800]

Video 1. Using a kPulley makes sense for arm assistance exercises. Elbow health and extension strength is vital for all athletes, not just those in throwing sports.

We know that some athletes will never use flywheels and others not for a year or so, and that’s not a problem. We have progression in mind from the jump because we tend to train athletes for long periods and built our business model on full-year clients. Also, waiting for an extended time before progressing to our more advanced equipment reinforces that the basics are a priority. Being disciplined and integrating flywheels slowly is not a punishment for athletes; it’s a way to make them earn their right to use the fancy stuff and progress.

With a few sets of 1-2 exercises, athletes can grasp flywheel training fundamentals & get hypertrophy & strength benefits without wasting time. Share on XFor coaches looking to enter the flywheel arena, we suggest arm exercises, single-leg training, single-joint training, and finishing sets of compound squats or deadlifts. With a few sets of 1-2 exercises, athletes will grasp the fundamentals of flywheel training and get solid hypertrophy and strength benefits without wasting time. I’m not promoting an overly cautious approach to flywheel training, but I also don’t recommend swapping all the ingredients out of your recipe as soon as you get a new mixing bowl.

Conventional Replacements for Main Exercises

In many circumstances, the next logical step is to swap primary barbell or machine exercises with the flywheel options. Depending on the athlete’s recovery ability and the program as a whole, coaches can swap out one day, one week, or one phase entirely and use flywheels. While this sounds bold, some teams spend entire training phases using isoinertial methods. We have not gone “all flywheel” yet, but find it a viable option for someone with a large arsenal of equipment.

Sequencing from single sessions or even parts of sessions before going all flywheel is the sensible way to progress, in theory. We’ve used the kBox as a belt squat for countless athletes, and some of our athletes find it’s a nice break from squatting when they’re in heavy training phases. We usually do this to bypass an issue like a shoulder or spine injury, though we’ve also had our heavy athletes do it with similar success.

[vimeo 381060239 w=800]

Video 2. Calf raises are great with flywheels and take a few sets to learn due to the timing of the eccentric pull. Experiment with tempos and rhythms based on what you feel you need with your athletes.

It is not, however, a 1-for-1 trade. I recommend increasing the rep range a bit when switching from standard barbell movements to flywheels. One consideration is that the increase in sets and reps will be more volume than some athletes are used to. Similar to any long term periodization, the key to success with isoinertial volume or loading is steady and manageable progression.

Steady, manageable progression is the key to success with isoinertial volume or loading, says @ExceedSPF. #FlywheelTraining Share on XRegardless of whether we include flywheels or not, we tend to reduce volumes in certain areas when we increase volumes in another. Before pre-season, we increase fieldwork and our time in the weight room drops off. We do the same for flywheel replacement. When we increase heavy kBox squatting for an athlete, we reduce their jumping or change of direction work on the field that week to allow for “fair trade.” Or we might simply reduce the amount of other eccentric work in the weight room.

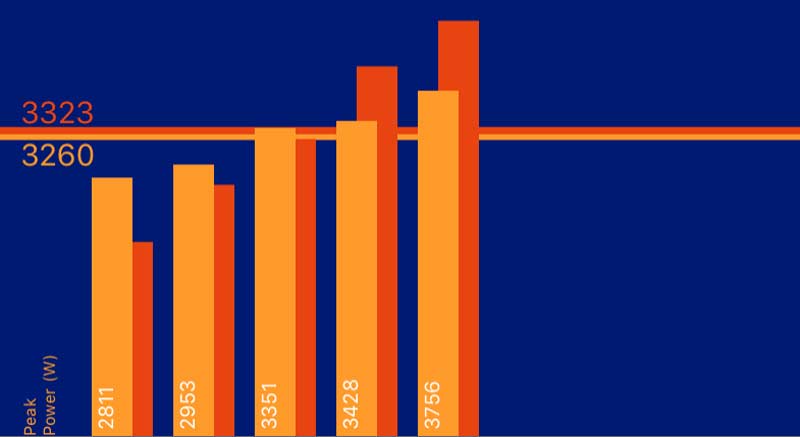

There's no point in doing #FlywheelTraining in a vacuum. kMeter readings help us quantify the training, and our force plates quantify the results. Share on XOther times, we do the opposite and complement heavy flywheel use with other eccentric and deceleration methods. Instead of having a pretty workout on paper and hope it works in a few months, we jump-test athletes and look at eccentric measurements as best we can. There’s no point in doing flywheel training in a vacuum. Our kMeter readings help us quantify the training, and our force plates quantify the results of all of the work done during each week or month.

Isometric Enhancement Techniques

There are two significant challenges with isometric work in team or group settings:

- creating an environment with an immovable object that works universally for all the athletes

- getting information regarding the effort of the contraction

We’re lucky to have tools for assessing force and effort as well as the kBox, which creates a unique and interchangeable immovable object very nicely. Whether you’re using the belt, harness, or an attachment for the upper body, you can adjust the length of the drive belt to have a custom-sized apparatus that works for all heights and strengths.

We can also add force plates to the ground or the flywheel’s platform to quantify the force or rate of force. This information shows us whether an athlete exerts sufficient effort early enough in the movement. One hard effort makes a difference and can be followed up with kMeter-guided feedback on the non-isometric repetitions that follow.

[vimeo 381060481 w=800]

Video 3. You can add isometric benchmarks with load cells or force plates, but a good honest effort is all you need to get started. Athletes can use various leg angles to get started, but the most common is a deep squat.

Potentiation, like flywheel work, is a continuum. (I’ll cover potentiation later in this post). You can use potentiation to spark a workout, break through career plateaus, or increase an effort for a single set or movement. For the sake of this post, we use a few sets of hard, overcoming isometric efforts to ensure the work is performed with real effort. You’ll appreciate real effort after a single bout with an immovable object if you’ve never done so.

As a side benefit, we’ve found that people with tendinopathy often experience pain at specific joint angles, which makes training hard a difficult task in logistics alone. With the kBox, we can adjust the belt length to circumvent the provocative range of motion and get some serious training stimulus without causing the athlete further anguish.

Ultra-High-Speed Flywheel Training

The highest velocity bouts on a flywheel require a little skill and experience, and decent athletes can grasp adding the extra spin after a few sessions. High-speed movements, especially squats, not only provide a great change of pace for athletes who train consistently at high levels but also are an excellent tool for athletes struggling to acquire deceleration skills.

The flywheel can get the athlete off the court or turf and minimize the typical stress of these activities, mentally and physically. The speed is fast enough to be realistic, slow enough to be safe, and the load realistic enough to make a difference. High-speed flywheel training is learning without teaching, and we love that.

#HighSpeedFlywheel training offers speed that's fast enough to be realistic, slow enough to be safe, & the load realistic enough to make a difference. Share on XSimilar to deceleration work, jumping can be too much for athletes during certain parts of the training block. Adding high-speed flywheel work can reduce a bit of the impact without compromising the eccentric forces we want on the tendons and musculature.

#HighSpeedFlywheel work reduces some of the impact without compromising the eccentric forces on the tendons and musculature, says @ExceedSPF. Share on XDepending on what part of the squat or jump you focus on, you can manipulate your equipment to modify how the movement is executed. Setting up the drive belt at standing height emphasizes the turnover and change of direction as the primary focus. By simply extending the length of the drive belt, you give the athlete the ability to drive past the standing position and incorporate a much more extension-based exercise that even involves the ankle.

[vimeo 381061115 w=800]

Video 4. Athletes can perform faster-than-normal squatting patterns with flywheel training without risk. As athletes practice the movement and advance, the speed can reach some impressive levels.

Similar to manipulating stresses with the flywheel, we sometimes switch out traditional jump work for high-speed flywheel squats. And we’ve even swapped elastic jump work for high-speed flywheel work. Moving fast in the weight room doesn’t necessarily translate to faster sprinting, but the emphasis on decelerating and accelerating the wheel with great intent is something not to overlook. Because speed and power work is neuromuscular in nature, you can consider this type of work learning rather than loading.

Potentiation Techniques

Potentiation is a lot trickier than social media would have us believe. If you’ve done it for some time and used measurement tools, you know that nothing works for everyone and everything works for some people. Consider this important question when implementing potentiation: Do you want to potentiate the main movement, the secondary movement, or both? So far, the research is clear that heavy or intense training temporarily primes the muscles used in these exercises. This makes flywheels an obvious candidate for potentiation.

The major flaw I see is the setup. Some people use so many movements, they look like they’re doing an obstacle course. And the setup is often far from practical or sensible. If the goal is to potentiate, spend time finding combinations of movements, reps, sets, and rest periods that allow the athlete to improve. Potentiation isn’t about trying to add more output following an exercise. It’s making sure the entire session will improve the athlete down the road.

[vimeo 381061938 w=800]

Video 5A. A good deal of new research is out on flywheels and potentiation. Make sure you read the protocols and repeat the specific loading and timing details in order to take advantage of the theoretical benefits.

[vimeo 381062204 w=800]

Video 5B. After flywheel training, you can potentiate resisted sprints. Most coaches prefer more contrasting styles of pairings, but tinker with exercises to see what works best for you.

When looking at the research, it’s easy to assume that if you do heavy stuff and then jump, you’ll improve. But realistically, you have to see the improvement in performance. We’ve all seen a spike in social media posts about French Contrast training, and it shows great potential. But what we know about Cometti’s method is that it’s possible to prescribe more than just squats and jumps.

We’ve used both upper and lower body potentiation methods for a long time now but only recently incorporated the flywheel in the plan. We use the flywheel for both heavy and isometric contractions paired with loaded and unloaded jumping or plyometric movements with promising results.

We've used the flywheel for both heavy & isometric contractions paired with loaded & unloaded jumping or plyometric movements with promising results. Share on XOne thing I like about the flywheel in terms of potentiation is the setup, as discussed in the isometric section above. Taking that a step further, you can use the same tool for an overcoming isometric, followed by ultra-high-speed squats and then to jumps without any crazy setups or playing Frogger through a crowded gym. Set up the flywheel with low inertia, move the drive belt to the isometric height, perform the iso, do the fast squats, and then unclip the belt and jump (on the ground).

Regardless of how you incorporate flywheels in your potentiation protocols, do so with purpose and results in mind. As cool and trendy as some of this stuff is, most of us are writing programs to improve our athletes rather than our following.

Contrast and Complex Training

Following a potentiation section, one might be fully aware of how to use contrast or complex training, and I’ll spare you the repetitive explanation. Contrast and complex methods with the flywheel don’t need to be complicated. Though we use some methods with more novice athletes, we gear most of our contrast or complex training toward our higher-level client who has a considerable amount of training time under their belt. At some point, athletes will approach their genetic ceiling and slow down. Sometimes a little change of pace using complex training can help these athletes make the minor gains they need at this level.

[vimeo 381061546 w=800]

Video 6. After conventional squats, athletes can employ rebound jumps immediately after their strength work. After the inertia and speed are refined on the lift portion, coaches can see a better jump profile over time.

Although it’s great to feel fast, it’s better to be fast. With contrast training, your athletes may feel fast after doing slower and heavier work. Having your athletes perform slow or isometric holds to contrast into sprints is excellent if it actually creates a faster sprint time or velocity. Flywheels have a role to play whether you use heavy-slow to fast-light or use fast exercises to improve firing rates in your slow, heavy work. When we do complex training with flywheels, we simply replace conventional exercises with flywheel or isoinertial exercises. Simple as that.

Accentuated Eccentric Overload

The most demanding of all eccentric overload methods are the accentuated options—any methods that go beyond 100% maximal effort. As soon as an athlete hits a load they can’t perform concentrically, they’ve entered extreme territory, even if it’s with only one kilo. The million-dollar question is how much overload past 100% of concentric ability is necessary to get a greatly accentuated overload. I have seen theoretical numbers like 10-20%, but so far we’ve experienced benefits from 5-10%.

[vimeo 381062610 w=800]

Video 7. Adding a shrug and your hips through the RDL will add more vertical force than the conventional exercise. Following the concentric motion with a bracing pattern does increase the eccentric contraction if timed right.

The biggest challenge in training is knowing how much overload is enough to make a difference. Since accentuated eccentric overload (AEC) is on the far side of the spectrum, it’s difficult to prescribe the perfect effort. In addition to the difficulties with selecting the right overload, flywheels are very dependent on feedback beyond the selected flywheel disc; you need to use the kMeter or you’re just guessing. AEC is no joke. If you choose to use it, you must be careful and have a solid understanding of an athlete’s past efforts and abilities.

I recommend sticking with the very familiar and primary movements when using AEC with the flywheel. Squatting and such make the most sense to me, as they’re the most familiar and are patterns people are used to loading heavily. If you’re not sure where to start in terms of loading, you can use traditional flywheel squats and look at the kMeter data to determine the athlete’s eccentric abilities. I’m sure you could also use force plate data or traditional squat information to create a map for your athletes.

It’s important to note, as most will understand, that AEC methods will bring along a considerable amount of soreness for some athletes. I’m not aware of much research that’s gone beyond short studies, but it seems like off-season training would be the time to incorporate these methods and save the athlete some in-season pain. It might also make sense to allow the athlete to auto-regulate the remainder of the session or even the training week in response to what happens after AEC training.

AEC workouts reset what is possible for less demanding training and raise the ceiling for resilience and athlete durability. You only need a few sessions to make real progress, so be cautious when first prescribing volume.

Advanced Training Is for Advanced Trainees

Just because an athlete is elite on the field doesn’t mean they’re an advanced athlete in the weight room. Of course, you should consider their level of ability. If an athlete has a low training age, you need to train them based on what they can do in training—not how good they are in their sport. Most of the exercises and training methods in this post will come in handy years from now if an athlete is new to flywheel training and for programming for experienced athletes. Experiment and see what works for you, as every training program is unique and must make sense for the athlete and the coach.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

[mashshare]