Not long ago, I wrote a post on social media stating, “The acceleration versus max velocity debate bores me these days. The reason you expose an athlete to maximum velocity is because it is the greatest stimulus that can be given to the nervous system.” I was not expecting much feedback from the Tweet outside of responses appreciating the use of the Randy Watson GIF, but conversation exploded both within the thread and outside of it. Before we continue, I would like to outline items I view as axioms.

The reason you expose an athlete to maximum velocity is because it is the greatest stimulus that can be given to the nervous system, says @HFJumps. Share on XSprinting Axioms

Sprinting at maximum velocity is a one-of-kind stimulus. The combination of force, ground contact time, and coordination required cannot be replicated. For example, I can achieve the forces via unilateral hops, but the ground contact time will be much higher. I could come close to ground contact times via assisted bilateral jumps, but the jumps would be bilateral, and the forces would be lower. Furthermore, neither of these activities require a coordination demand which is even close to maximum velocity sprinting.

Sprinting at maximum velocity is a one-of-kind stimulus, says @HFJumps. Share on XTraining at maximum velocity also trains acceleration, because one must accelerate to reach maximum velocity. The only possibility for this not to happen is to be placed on a high speed treadmill, but that is even debatable, and not applicable to most.

Training acceleration does not necessarily guarantee maximum velocity will improve. If a person trained by only performing 10m sprints, an improvement in top end speed would be unlikely. However, if the same person also did 40m sprints on another day, then improvements in top end speed would be likely. Yes, there are probably exceptions to this, but in general, training acceleration with an expectation that maximum velocity will improve is a faulty strategy. I know because I have made this mistake more times than I would like to admit.

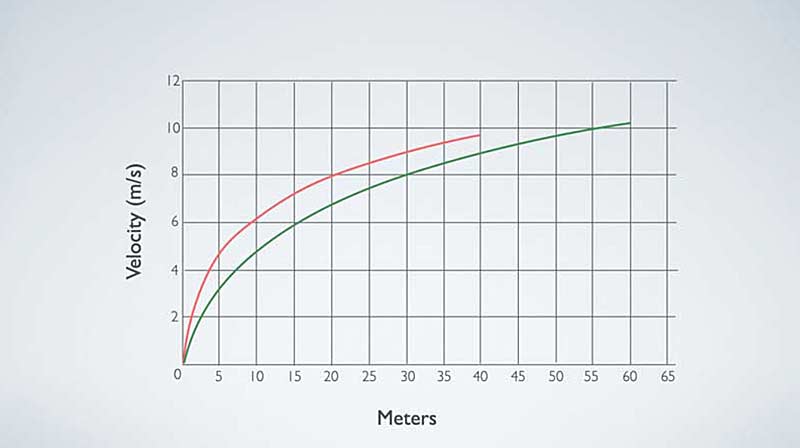

When it comes to sprint training, instantaneous velocity is a better metric than average velocity. Unfortunately, most programs do not have a device like the MuscleLab Laser or 1080 Sprint which gives this metric. If you utilize timing gates or Freelap, the metric you receive is an athlete’s average velocity between the gates. The advantage of lasers, a 1080 Sprint, or Dynaspeed is that they allow a coach to see the full sprint profile (hypothetical graph below), which gives better data to determine interventions necessary in training.

Repairing Cracks in the Foundation

I think it also necessary to set the table as to why the majority of the information I put out promotes sprinting. I believe the three biggest issues with youth athletic development are as follows:

- Early specialization.

- A wider base of coordination allows for a higher ceiling. Kids should be exposed to a variety of gross motor patterns, and they will transfer to sport-specific skills.

- Lack of free play.

- The number of items which keep kids at home and sedentary is constantly increasing. In 1990, if I wanted to play video games with a friend, one of us had to ride a bike to the other’s house. Chances are we would get tired of the game and go outside and play. Now kids do not have to leave the house to play video games with one another, and when they get bored with the game, it is often too much work to go outside and play!

- Youth sports are predicated on a conditioning model as opposed to a high performance model.

- The youth through high school practices I observe rarely offer athletes the opportunity to sprint with full recovery. Much of the training produces repeatable, but average, output. This puts a limit on the ceiling an athlete can attain.

In the Just Fly Performance Podcast #233, movement and speed guru Lee Taft stated the following in regards to youth learning a skill:

When I teach athletic movement skills…whenever possible, I think athletes have to be taught to react and go full speed so that their central nervous system adapts to the speeds in the limb control that they need. If younger kids are taught to move fast, and we gradually build in the technique, they are going to be okay…. When they get older, if they have had exposure to that speed, they can grow off that.

I think this can be applied when discussing the stimulus of sprinting—give youth athletes exposure to maximum sprinting and develop technique as you go. Before proponents of sub-maximal work go crazy, this can certainly include slowing things down at times to get athletes to feel certain positions and movements! However, especially with younger athletes, maximum intensity should almost always be present multiple times in the weekly program.

While I try to address these three items through my social media presence and writing, there is no question that I spend the most energy addressing sprinting at maximum velocity. I think specialization and lack of free play are structural issues that require a shift in society. In other words, these are really, really, BIG problems. Incorporating sprinting is something that can be done within our current structure that does not completely fix it, but does make it better.

I think specialization and lack of free play are structural issues that require a shift in society, says @HFJumps. Share on XTwo Loves

Since I promote maximum velocity sprinting, I have been placed by some in the “maximum velocity crowd” of coaches. I have no problem with this, but being pro-maximum velocity does not mean I am anti-acceleration. Sometimes it is okay to have two loves in life. For example, I love Lou Malnati’s deep dish, but I LOVE my mom’s homemade pasta sauce (gravy for the Italian readers). Sometimes, I have them both during the same meal, and that is basically the stuff that dreams are made of. That is what I view a sprint with maximal acceleration where maximum velocity is attained. I call it a max velocity blast.

Having a weekly acceleration-focused day is logical, says @HFJumps. Share on XEven in a hypothetical piece where I pushed the limits of maximum velocity dosage, I finished with stating that having a weekly acceleration-focused day is logical. Furthermore, one of the most important lessons I have learned in the nuts and bolts of writing track and field training programs comes from Marc Mangiacotti: train acceleration in some way, shape, or form every single training session. This can be done via the exercises listed below, which can be appropriately placed in maximal, submaximal, and regeneration training sessions:

- Sprints of 5m-30m

- Possible starting positions: two-point, crouch, rollover, kneeling, push-up, three-point, four-point, and block.

- Resisted Sprints and/or Marches

- Jumping

- Large flexion present in hip/ankle/knee such as a broad jump.

- Multi-Throws

- My favorite is underhand forward as it allows the athlete to unfold and translate forward.

- Wall Switches

- Wall Push to Vertical

- Athlete leans into a wall at an acute angle and marches toward the wall, feeling how the pushes into the ground contribute to posture becoming vertical.

- Cusano Hurdle Push

- Low Lunge March

- In my opinion, this is the best exercise in Chris Korfist’s arsenal (he calls them Chuck Berry Walks), but few will do them consistently because they are not sexy enough.

- Overcoming Ankle Isometrics

- Acceleration-Themed Weight Room Activity

- Squat, split squat, hex bar deadlift, Olympics from the floor.

Blurred Lines

Where is the breaking point for when a sprint workout shifts from becoming acceleration focused to maximum velocity focused? The standard measurement in track and field training is 30 meters, but that does not really tell the story. Defining if the focus is early acceleration, late acceleration, peak velocity, or exposure to speed decay (what happens post-peak velocity) is probably a better structure, and as one works their way up this chain, the previous item(s) are being addressed.

Like many coaches, I enjoy research and I use it to assist with creating generalizations for program design. However, I also know that individualizing training as much as possible tends to lead to higher achievement. It should be noted that most of my career has consisted of 40:1 athlete to coach ratios where I was responsible for three event groups (sprints, hurdles, high jump). Because of this, I have experience with trying to meet the instructional demands of a large group while maintaining smooth workflow within the various constraints of our facility. So how can one individualize in a large group setting in regard to sprint training?

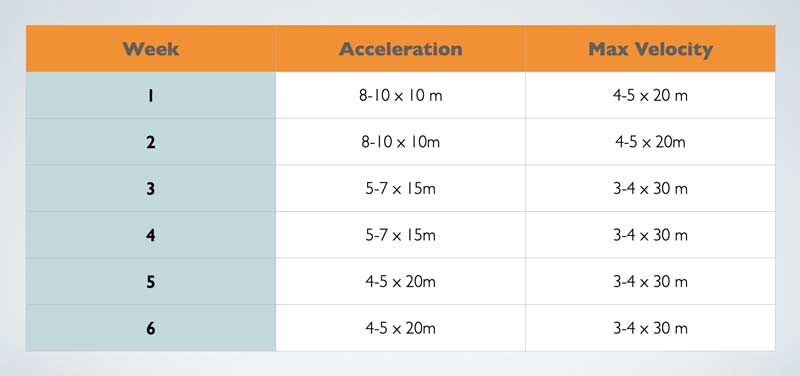

The difficult part is providing each athlete with technical feedback. There is no question it can be overwhelming, but it is one a coach must undertake because it is a great way to build trust with the athlete. People respond well to people who show interest in them. Programming, at least at the high school level, does not have to be nearly as difficult as most athletes will fit into a relatively general progression. For example, a simple off-season training program for a field/court sport could be:

In addition, on acceleration days, I would include deceleration-acceleration and/or change of direction work after the sprints. On maximum velocity days, I would include curved and/or serpentine running before (and/or after) the sprints. I have noticed athletes respond well to linear sprinting after a rep or two of curve work. Creative coaches could even combine these concepts together: timing 20m coming out of a zero degree cut or timing a 10m fly coming off of a curve. The possibilities are endless.

My guess is a program such as this would meet the needs of at least 80% of high school athletes. For the other 20%, who tend to be veteran athletes in the program, advanced variations such as longer sprints or sprint-float-sprints may be required.

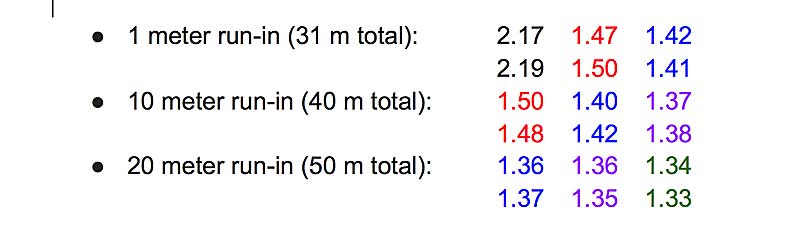

An easy way to determine if variations are needed can be done through observations followed by a simple test. Let’s say that an athlete has been stuck at the same 10m fly time and it does not appear that normal cuing and suggestions are creating an improvement. If the 10m fly included a 30m run-in, the coach can create a new training stimulus and assessment by:

- Giving the athlete an additional 10m in the run-in, making the total sprint 50m

- Creating three timing windows: 20m–30m, 30m–40m, 40m–50m

The test becomes a 30m fly with a 20m run-in. We know most young athletes hit top speed somewhere between 20 and 30 meters, but the comparison of the three splits would give a coach a better idea of where peak velocity is occurring. The reason I say better idea is that it cannot be said where peak velocity is occurring unless you have an instrument which measures instantaneous velocity, which timing gates do not. To illustrate, here is an example of splits from a high school female I have worked with.

The fly zone was 30m with a Freelap cone every 10m. The following was done on the same day. Two reps of each. The times are color coordinated to represent the segment covered. Red: 10m–20m. Blue: 20m–30m. Purple: 30m–40m. Green: 40m–50m.

The fastest split displayed occurred on the last split of the last rep. As a side note, I was surprised by the performance of the first 20m run-in rep, so on the second, I set up another 10m segment to time 50m-60m. The time was 1.43. Based on the average velocities on last repetition with the extra 10 m segment, I can assume that peak velocity took place somewhere between 20m and 50ish-m.

Many would make the assertion that peak velocity must have occurred during the split of 1.33, but that is not necessarily true. The only guarantee about an instantaneous velocity is that it has to equal the average velocity at one or more points during the interval (this is the Mean Value Theorem in calculus). In other words, peak velocity could have occurred during an interval with a lower average velocity. An example similar to this is as follows:

- Two cars travel a 100 mile distance.

- The first car travels the entire distance at a constant velocity of 100 mph. The average and peak velocity are 100 mph. The time taken to cover the interval is one hour.

- The second car travels the first 50 miles at 200 mph, but the second 50 miles at 25 miles per hour. The peak velocity is 200 mph, but the average velocity is 44.44 mph. The time taken to cover the interval is 2.25 hours.

- Therefore, the second car has a higher peak velocity (200 mph versus 100 mph), but a lower average velocity (44.44 mph versus 100 mph).

The takeaway from this is that a coach can use this type of test once every four to six weeks to help determine where peak velocity may be occurring, and then target that interval, and possibly go beyond it, during training. In the example above, I walked away confident that the athlete received training at maximum velocity, and it helped me construct future training sessions for her next block.

We all can only do the best we can with what we have, says @HFJumps. Share on XCommon arguments against using a fly 30 meter with a 20 meter run-in are:

- I do not have the space!

- A real issue to be sure (especially in the winter months). We all can only do the best we can with what we have. However, I would try to find a way to make it work outside when the weather cooperates.

- I am afraid of athletes getting injured.

- Another legitimate concern, but if training is progressed at a reasonable rate, the risk would be minimized. Coaches need to analyze the risk versus reward in their setting. I tend to go resort back to ensuring athletes will be able to handle the demands of maximum velocity if they are faced with it in competition.

- I do not have the time.

- If you are already performing sprints with your athletes, I would beg to differ. A workout of 4 x 20m would take about 10-12 minutes. 2 x 50m would take the same amount of time. It would also not have to be done for every single athlete—just those who have made it through your progression and may need alterations to get through a plateau. If you think it would take more than 12 minutes in your setting, I would consider omitting a lift or plyometric once every four to six weeks to perform the test.

- I do not have the equipment because of budget concerns.

- Timing with software like Dartfish is not friendly in a big group setting, but it is budget friendly, and can be done for the small number of athletes who are in need of greater stimulus.

Why Maximum Velocity Matters

I have had numerous conversations with field and court sport coaches who are all about sprinting, but only work up to 20m or 30m. Their reasoning is that their athletes will rarely sprint beyond 20, so why train beyond it. I typically respond by asking how many times they have seen an athlete in their sport with a barbell on their back during the game.

A coach cannot argue against maximum velocity training because it is not specific, but think squatting/deadlifting/pulling/pressing is the answer to every question. Training is often at least a generation or more removed from sport, and often includes items which are an incredible stimulus, but do not occur in competition. We need to be okay with this from both a weight room perspective and a sprint perspective!

Another argument I receive as to why sprints over 30m are not necessary is based off of research done by Ken Clark’s group on the 40 yard dash at the NFL Combine. The study found athletes reached 93-96% of their maximum velocity within the sprint by 20 yards. Similar findings are shown from Nagahara’s group in a study of 18 male participants who hit 95% of maximum velocity at 23.1m. It is worth noting that the participants in the study had 100m bests in a range of 10.54–12.30 (mean +/- standard deviation of 11.28 +/- .36), which corresponds nicely to high school males!

The argument given is if athletes are hitting 95% of maximum velocity prior to 30 meters, isn’t sprinting to 30m enough? In my opinion, the answer is a resounding no, and here is why.

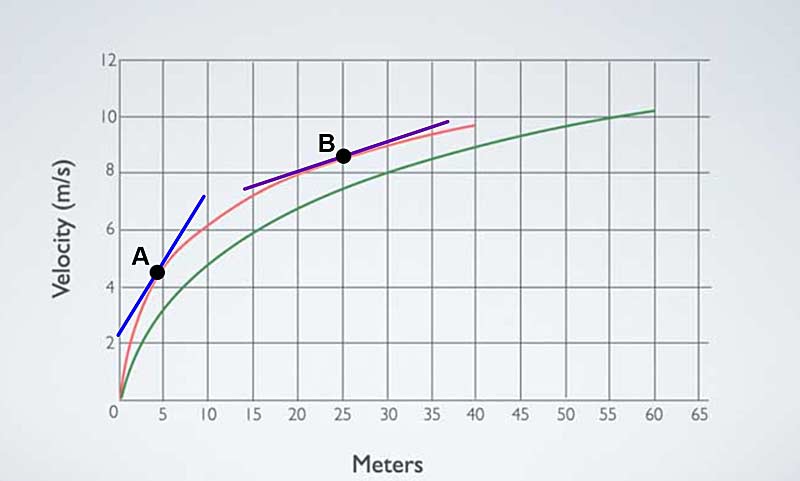

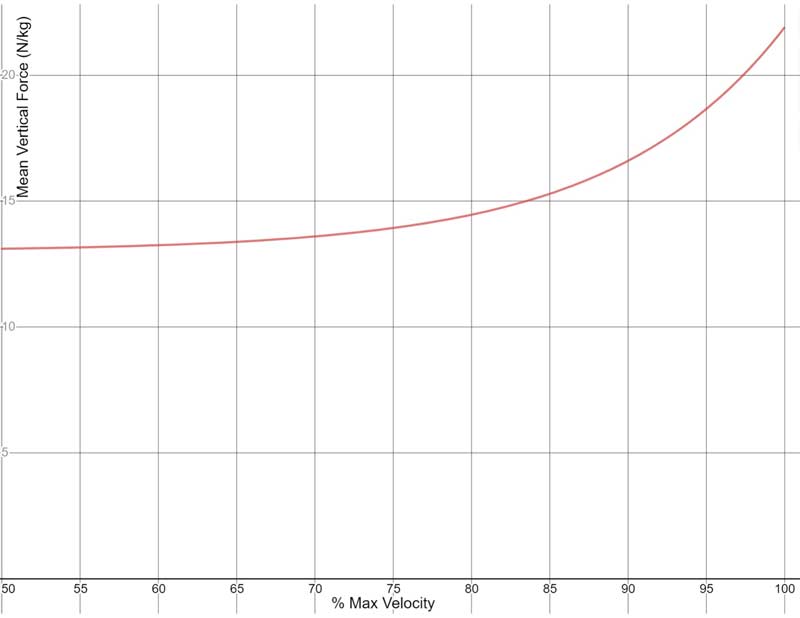

Both the aforementioned study by Nagahara and another (21 males, 100 m bests 11.27 +/- .27) give vertical forces of each step over the course of a 60m sprint. The results show logarithmic growth, meaning that forces are increasing at a decreasing rate. The visual below will help make this clear, as the velocity curve shown earlier is also logarithmic.

In both studies, vertical forces began to level off between steps 13 and 15, meaning that beyond this, increases in force were relatively small. For spatial reference, most high school males will hit the 20m mark between 12 and 14 steps, and the 30m mark between 16 and 19 steps (exceptions exist of course).

To digest what I will outline here, it may be helpful to view every step in the sprint as an individual repetition. If we were dealing with an athlete in the study that was near the upper end in terms of 100m performance, and the workout of the day was 20 meter sprints, he would not get any repetitions of steps where forces begin to level off. If the workout was 30m sprints, he would get around four. If it was extended to 40m sprints, around eight or nine total. The point here is that just beyond 20 meters is where forces and contact times are starting to provide a unique stimulus, and athletes should be exposed to that stimulus! While there is merit for sprints of 20m and lower (improving acceleration is important), not going beyond that distance is definitely leaving something on the table!

While there is merit for sprints of 2m and lower…not going beyond that distance is definitely leaving something on the table, says @HFJumps. Share on XSo now you may be thinking that 30 meter sprints would be enough. To quote Lee Corso: “Not so fast my friend,” and here is why. The studies stated vertical forces began to level off at step 13 and beyond, following the logarithmic model. However, in a mean vertical force versus percentage of maximum velocity graph, Nagahara’s group showed this relationship follows an exponential model.

The graph below shows an exponential curve to provide a visual, but it IS NOT an accurate depiction of what was found in the study. For our purposes, we just need to understand the exponential behavior of vertical force as the percentage of maximum velocity increases. The function below shows mean vertical force increasing at an increasing rate (the slope of the curve is getting steeper as the percentage of max velocity increases).

The reason why this is important is that if athletes do not get higher percentages of maximum velocity (especially 90% and above), they are missing out on the exponential increase in force. As stated earlier, one of the Nagahara studies found the participants hit 95% of maximum velocity at 23.1m. Like before, if sprints are capped between 20m and 30m, the exposure to the portion of exponential increase in mean vertical force is minimal.

Parting Thoughts on Peak versus Acceleration

We also need to take exceptions into consideration. Let’s say there are two athletes who have made it through a sprint progression up to 30 meters and Athlete A reaches 100% of maximum velocity by 25m, but Athlete B reaches 95% of maximum velocity at 30m. Here the same workout is giving the two athletes different stimuli, and the reality is Athlete B is getting short-changed.

This example is also why it is important to attempt to determine where an athlete is hitting peak velocity—so workouts can be designed up to and beyond that point. Acceleration work is extremely important, but exposure to steps at 95+% maximum velocity matter, both in the lead up to peak velocity and the time after as speed begins to degrade. The forces, contact times, and coordination demand cannot be replicated.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

So if a high school athletes is sprinting twice a week and using the template above can you throw in a couple of runs in the 50-100m range to cover their bases and get some effect at the longer distances? Fantastic article too

TY Austin! In general, I would say “it depends.” I think it can certainly work if the program’s progression is appropriate.

Really we have come to accept certain things as being correct, right, really absolute, without investigating. If you reach maxV, top end speed in the 100m, surely you are decelerating anything after 70-80, because that is typically the distance folks associate with top end speed on the elite level, forget lower levels, that is 50-60, let it be said. So if that is the case, anything after those distances for those levels, is deceleration, so there is no closing speed in the 200, 400m, if one reaches maxV at a certain point, again what is that certain point and what are all of the variables that effect this? Because whenever there is an effect, you will have a cause. For example what caused Noah to break the American record in the 200m, the effect, was the American record. Could he possibly have been decelerating for 120 meters, once he reached maxV at 80 meters? I would say there is no way, he breaks the record if that were the case.