I have spent a significant amount of time via a variety of mediums addressing the importance of sprinting in training. One driving force behind this has been to sway coaches away from coaching as they were coached. In many of those cases, the driving force behind training was volume, with intensity being neglected.

While trying to persuade coaches away from 8 x 200-meters or gassers multiple times a week is a needed conversation, I think it is important to ensure that the conversation for those who incorporate sprinting in their training programs moves forward. Whether you are a track coach or a field/court sport coach who programs sprints, I hope you consider embarking on this journey with me. Before we approach top end speed together, however, we must identify the elephant in the room—some coaches who believe in the power of sprinting are cannibalizing all who believe in it by unintentionally devaluing sprinting.

Some coaches who believe in the power of sprinting are cannibalizing all who believe in it by unintentionally devaluing sprinting, says @HFJumps. Share on XOne benefit of social media is it increases the amount of interaction among coaches. Novice coaches can gain insight not only from others like themselves at the base of the pyramid, but also from those at the apex. Accessibility has never been greater: a true gift in most cases, but a curse in others. It seems to be a weekly occurrence that I come across social media conversations on the best way to train sprinters—amongst people who believe sprinting is a quality training stimulus. The disconnect between those in the conversation and those witnessing it is often the context of who is being trained. The danger is that the conversation among coaches of elite athletes and their beliefs within their population can be read and applied by coaches of novice athletes. This can be a big problem.

Although progress has been made with there being more true sprinting sessions in youth through high school sports, it is still in the minority. Much of the training that occurs is still predicated on a conditioning model, not a performance model. When coaches of the elite comment that the athletes they coach do not need to sprint at 100% intensity in a training session to get faster, I am sure they have their reasons and data to back them up. The potential danger I see is coaches of novice athletes (particularly those who follow a conditioning model) seeing this and believing their young male athlete who runs a 40-yard dash in 5.82 does not need any sprinting at 100% intensity to realize maximum gains. This feeds confirmation bias, and often ends up with athletes experiencing “tempo hemlock.”

While I may appear to throw stones here, that truly is not my intent. By nature, I hate conflict, and the remainder of this article will focus on how I feel the worlds of maximal and submaximal sprinting can coexist. I’ve gone into detail as to what I feel is maximal sprinting in previous work, but a short synopsis for my context is anything that reduces speed from an athlete being spiked up on a track is submaximal. This leaves towing, running with the wind, and competition as the only possibilities for supramaximal training. For a field/court coach, being spiked up on a track could be considered to be supramaximal because athletes have a great chance of hitting higher velocities than they would on the field/court.

Before moving forward, I will offer the disclaimer that I am far from a one-size-fits-all coach. Within my context I do the best I can to address individual needs, and I have coached athletes who do not fall cleanly into a bucket. Do not view this as gospel, but rather options to consider as you continue to carve your own path.

Targeted Training

My own weekly programming for high school track and field athletes has included an acceleration-themed day and maximum-velocity-themed day for longer than I can remember. I think having a focused day for each is a logical approach. Simply put, acceleration sets the table for an athlete attaining their true maximum velocity. Too much focus on maximum velocity can create what Jake Cohen refers to as “frequency monsters”—sprinters who hit a false top speed too early because they shortchange acceleration. Having a day dedicated to its rehearsal with sprints 30 meters or less and performing various drills daily to get athletes comfortable with positions attained in the early part of a race goes a long way in laying the foundation for a complete sprinter.

In the past I have said training at maximum velocity is the best two-for-one deal in training because in order to attain maximum velocity, athletes must work through acceleration. While I still feel this is true, there are limitations. First and foremost, reps where the target is maximum velocity tend to be longer, and therefore pose more fatigue to the nervous system, thereby limiting volume. Second, if an athlete begins the repetition from a three- or four-point start, the angles found in accelerating from these positions pose a greater demand on the musculoskeletal system, which can also limit volume.

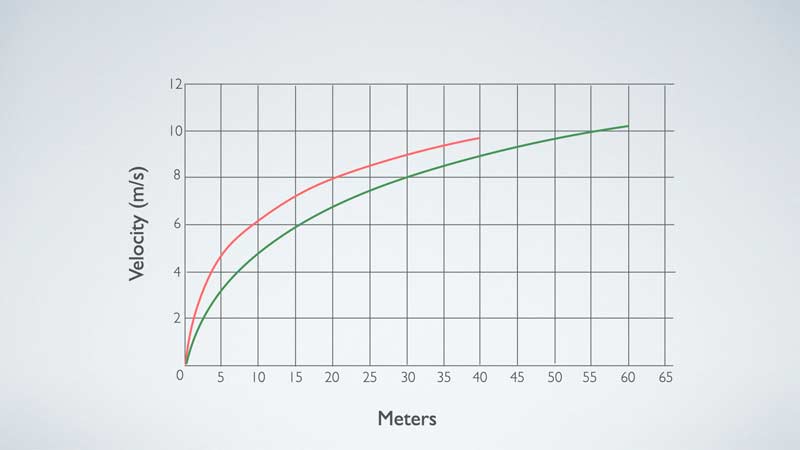

Stimulate, don’t annihilate, says @HFJumps. Share on XWith these limitations in mind, we must dig deeper and discuss how maximum velocity is being attained. One way is to blast 100% from the get-go (max velocity blast), as if it were a competition. A strength of training in this manner is the athlete working through a race-like acceleration prior to reaching top speed. The other method would be an acceleration bleed, where the athlete accelerates submaximally over a longer distance prior to attaining top speed (max velocity bleed). While the athlete is not experiencing a race-like acceleration in this situation, what I have noticed is that many athletes end up with faster fly times. Due to the benefits found in both methods, my current philosophy is to include both within a training week.

Video 1. Here the athlete accelerates maximally (as if the rep was a race), and a 10-meter fly time is captured. Although not done in this example, you could capture a full rep and a fly time with this method.

Video 2. This shows the athlete accelerating submaximally, with the target being as fast as possible between the timing gates. The full rep time is irrelevant—the athlete focuses solely on monitoring his speed to be as fast as possible between the gates.

When in doubt, a coach should think about what the target is for the day’s training. If the sole purpose is to attain the highest velocity possible, the beauty is that you can use either method (blast or bleed), depending on with which method each athlete tends to hit a higher velocity. Coaches can also work in competitive reps periodically to keep things fresh or help athletes bust through plateaus.

Training Arrangement

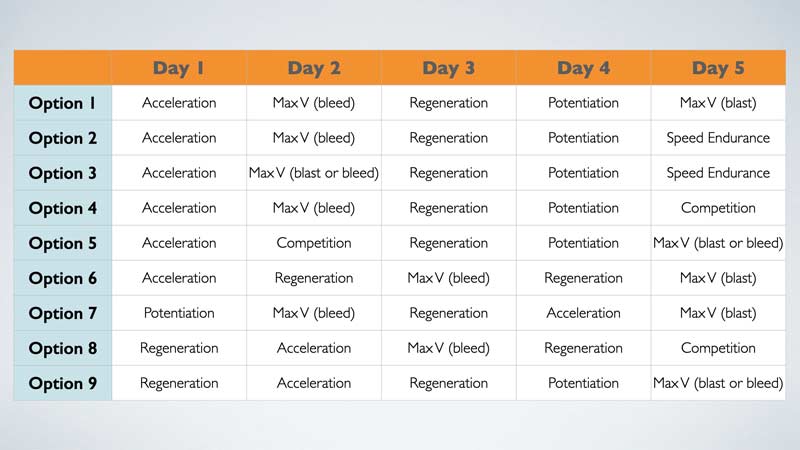

Having discussed three different options for training sessions (acceleration, max velocity blast, max velocity bleed), the next logical item that I must address is how to arrange them within a training week. The table below shows possibilities for a five-day training structure for high school track and field. Field/court sport coaches obviously have different demands and may only be able to fit in one of the aforementioned sessions within a week.

In each of the sequences above, the focus was on how to make it feasible to place three high-intensity training sessions in a five-day structure. Here are some key points that would be necessary for this to work:

- Most coaches put an acceleration and maximum velocity (blast or bleed) day back-to-back. The thought behind this is for the acceleration session to “wake up” the athlete’s nervous system coming off of a weekend and lead them to hit top end speed the following day. Many would say you need 48 hours between neuro days, but if the volume is low enough on the first day to where it stimulates but doesn’t crush the nervous system, back-to-back placement is doable (especially with young athletes). Tony Holler’s mantra, “Don’t let today ruin tomorrow,” is sound advice here, and would also apply in the weight room. If you would like to lift on the first day of the back-to-back, I would advise upper body only, lower body with no eccentric component, or light Olympics. However, my general advice would be to save the weight room for the second day because of the recovery that follows.

- I personally prefer placing the max velocity bleed after the acceleration day because I feel their differences make them a sound pairing. On the acceleration day, the athlete will be pushing from deeper angles at ground contact, while the max velocity bleed style can be shallow angles throughout. With that being said, I have placed a maximum velocity blast after an acceleration day and have not had any issues.

- If you would like to dive into deeper volume with acceleration and have a heavier lifting session, which may include lower body lifts with the eccentric portion, you could follow a traditional high-low model as in option 6.

- In regard to a weight room session later in the week, I would recommend the following:

- Lift on day 5 as long as it is not a competition or speed endurance day. I’ve had athletes lift on speed endurance days, and I’ve realized I was an idiot for two reasons. First, it is just a cruel thing to do. If you ask an athlete to sell out during long sprints, do not put anything on the back end that will take away from the effort on the sprints. Second, a major purpose of the long sprints is to teach athletes how to tolerate being acidic. Henk Kraaijenhof points out that activity after the sprints assists the body in clearing acid, and that we should not provide the assistance. Make the body learn how to clear it more efficiently on its own!

- If day 5 is speed endurance or a competition, you can prescribe a lifting session on day 4 that will not render the athlete useless the following day. The stipulations made earlier for lifting on the acceleration day would be wise to follow here as well. Stimulate, don’t annihilate.

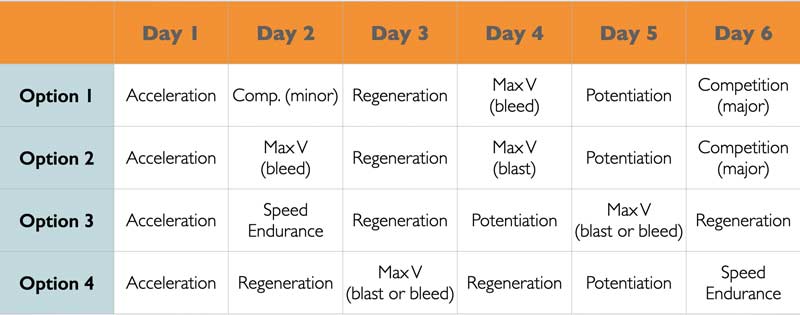

- Many track programs operate on a six-day calendar. Here are a few possibilities:

What About Sub-Max Intensity?

The initial premise of this article was to showcase how the worlds of maximal and submaximal sprinting could coexist, and I’ve spent nearly 2,500 words describing how to structure maximal sessions. This is by design, as I think it has the largest impact on improving performance, and everything else can fall into place once the high-intensity days are set. Most of the weekly options presented above include a regeneration day and a potentiation day, and in 8 of the 13, they are back to back.

I think maximal sprinting has the largest impact on improving performance, and everything else can fall into place once the high-intensity days are set, says @HFJumps. Share on XWith the throttle being revved up early in the week, there needs to be a period where it is brought back down. The regeneration day is the primary spot where this would happen. The activities that can occur on these days are endless. Some options are: low-intensity bodyweight/medball circuits, auxiliary weight room exercises, pool workouts, submaximal sprinting, or instructing an athlete to find a nice place in nature to take a 30- to 60-minute walk.

When a potentiation day follows a regeneration day, its typical purpose is to bring the throttle back up so the athlete can perform their best following the potentiation day. The prescription for the potentiation day is truly an n=1 situation. The exploration of options that fit each individual athlete is where the art and science of coaching meet. I’ve had athletes whose most effective potentiation days were a day off, ones who favored a low-volume/high-intensity day of sprinting/plyometrics/lifting, and others who liked something in between.

While the high-intensity sessions are the most important for athlete progress, mismanagement of the regeneration and potentiation days very well could be the most common cause for athletes failing to improve. Activities that are too difficult to be restorative or not intense enough to potentiate probably occur more often than we care to admit. Target the mean initially, but don’t be afraid to experiment in the middle of the season to get an idea of what will work best when all the chips are on the table.

Tempo

There is certainly an overlap between restorative and potentiation days. One activity that could occur within either is tempo running (extensive or intensive). If you use tempo running on a restorative day, you must remember that you are using it to aid recovery. I personally have found this to be a challenge to manage, so I have decreased my use of tempo quite a bit. If I use it, it is usually in conjunction with a circuit of exercises to help avoid repetitive stress on the body. Here are some guidelines that I find helpful:

- Even though the intensity may be submaximal, reps should still look like sprinting. If it doesn’t look like sprinting, athletes are just rehearsing bad habits. I was guilty of putting athletes through reps that ended in a death march on regeneration days in the past. Regeneration’s purpose is to assist recovery, not result in requiring additional recovery.

- I used to prescribe percentages and target times, but I have found that to be almost comical at the novice level. Does a high school athlete really know the difference between 70% and 80%? Furthermore, perceived percentages vary day to day, so today’s 70% may produce a 28-second 200-meter, but next week may require 80% to hit the same time.

- I have stolen one of the sprint words from ALTIS and instruct athletes to “be at peace” during repetitions. I find this usually does the trick in getting the shapes to look like sprinting, while also allowing the athlete to focus on the execution of a technical item during a rep.

- Besides the recovery component, the increased ability to control movement at a lower velocity is another reason why tempo sessions can be effective. I expect there to be an argument as to whether submaximal sprinting technique translates to enhanced maximal sprinting technique, but I offer the following to ponder: In the long and triple jumps, the only full approach jumping we do is in competition. Athletes jump in practice with short approaches (usually a max of 75% of the competition approach). Even though athletes only do the highest-intensity version of the event in competition, their technique improves. Joel Smith often cites the Rewzon long jump study, and for good reason. In my experience, athletes are better developed with a spectrum of intensity.

- When using tempo for recovery, I have found that we don’t usually need timed recoveries. Just telling the athlete to begin the next rep when they are ready tends to work. If possible, a better solution is to monitor heart rate by ensuring it is hanging in the aerobic zone (120-150 beats per minute) and not getting into anaerobic threshold (170+ beats per minute). If an athlete cannot speak in complete sentences, they are working the reps too hard and/or not resting enough.

- Two of my go-to tempo recovery workouts are diagonals and segment runs. Diagonals have the athlete run the diagonal of a football or soccer field and walk either the length or width of the field for recovery based on rep intensity. They then run the other diagonal and repeat. Segment runs find the athlete running “at peace” for a prescribed time. For example, the athlete will run the first rep at 20 seconds. A mark can be placed for reference. Then the athlete will rest and repeat. The coach and athlete can make note of where the athlete finishes each rep to adjust rep intensity and recovery time.

- In general, I am a bigger fan of monitoring time as opposed to distance because it is a better way to monitor workload with large groups. I can walk away knowing they all ran for the same amount of time, which is not the case if distance is the tool to measure rep length.

- With track and field athletes, I prefer tempo sessions to be done on turf or grass. It is easier on the body and exposes the athlete to a different stimulus. Another option is to toggle back and forth between grass/turf and the track for a potentiating effect.

- Tempo on a regeneration day is not the best option for many athletes, so other options should be used. A portion of this group, however, does respond well to tempo work for potentiation the following day. Follow the guidelines listed above.

- Yes, you can also use tempo to get the athlete into anaerobic threshold. I am not a huge fan of voluming athletes at 80-85% to get there, but I have had athletes who feel the need to do that type of work. This would occur on a speed endurance day in the tables above, and I would have the athletes go through a circuit of varied activities prior to completing the tempo workout. Lactate levels would rise during the circuit, which would allow running volume to be lower, while still hitting the desired acidity. You can also use multidirectional work to get lactate levels to rise in both the field/court sport and track settings.

Wickets

Vince Anderson and Ron Grigg have put out invaluable information regarding the use of wickets. They are prescribed as a maximum-velocity drill, and what I have found nice is I can use them on any training day. This includes acceleration sessions. I do not see any issue with closing an acceleration-themed workout with a couple wicket runs to springboard an athlete into a maximum-velocity session the following day.

I mentioned earlier that anything that causes speed to be reduced is considered submaximal, and for the vast majority of the high school athletes I coach, wickets cause speed to be reduced. In my experience, it takes a long history with wicket runs to be comfortable enough to roll through them at true maximum velocity. For many athletes, the forebrain is involved due to the threat of hitting a hurdle and stumbling.

You can use wood slats or tape/chalk for those who are tentative because of this. Another option that minimizes the risk associated with using actual hurdles is the use of the Power Systems Versa Hurdle. Although they are more expensive than a traditional banana hurdle, they stack/store nicely and do not get tangled up in an athlete’s gait if they nick or step on a hurdle. I haven’t lost an athlete to injury using banana hurdles, but it makes sense to try to eliminate the possibility.

Chris Korfist has had the biggest influence on my use of wickets. My main takeaways are manipulating surface, spacing, arm position, and external resistance to achieve desired results for an individual. The beauty is you can match various combinations of these variables to fit the training. Utilizing Chris’s methods has paid huge dividends in improving our athletes’ sprint techniques for years, and I strongly recommend investing in his many resources on the topic.

To the Runway

I spent the first 12 years of my coaching career focused on the sprints and hurdles. Shifting over to working primarily with jumpers over the past six years has helped me develop a better understanding of speed. When I first started coaching the jumps, my lone goal was to get jumpers to buy into the reality that if they became better sprinters, better jumps would follow. Jumpers always want to spend time at the pit (and I do not blame them), but my go-to phrase with them continues to be “crap on the runway does not turn into diamonds in the air.” Although there were some growing pains, our jumpers improved rapidly, and buy-in was sealed.

Since our goal was to make them better sprinters, one of the items we chased was infinite speed, and our athletes would undergo timed sprints in training once or twice per week. The thought was “faster times, better jumps.” Again, while I think that is true in many cases, it was not a cure-all. One, if an athlete moved faster, but with the same errors in sprinting technique, better jumps did not always occur. Once an athlete leaves the ground, the errors they have in sprinting are compounded, and a faster take-off velocity may not be able to mask those errors. The athletes who found the most improvement were those with simultaneous sprint technique and velocity improvement.

I have found that jumpers tend to have a better ‘feel’ of speed than pure sprinters. I think this is because of the time they spend on the runway, says @HFJumps. Share on XI have found over the past few years that jumpers tend to have a better “feel” of speed than pure sprinters. I think this is because of the time they spend on the runway. When completing full approaches, most are operating between 80% and 90% of their maximum velocity at takeoff. I think the rehearsal at this speed gives them a better feel for toggling throttle, which is beneficial in any race more than 60 meters. It also allows them to execute the quintessential throttle control workout of sprint-float-sprints with a higher degree of proficiency than their peers.

Sprint-Float-Sprints

Sprint-float-sprints (or ins and outs) involve a period of acceleration followed by toggling segments of maximal and slightly submaximal sprinting. In my approach, the acceleration portion can be a bleed or blast, and can range from 20-50 meters depending on the method used. I like to capture the times of each of the sprint-float-sprint (SFS) segments when possible to use as a teaching tool for athletes.

What I have found with 10-meter segments of SFSs is the float segment ends up being the fastest for around half of the athletes when they are new to the workout. This is a marriage of the subjective and objective. Coaches can often see athletes having excessive tension in their races/sprints and instruct athletes to “relax.” The SFS shows them that when they “try less,” their mechanical timing improves, and they run faster.

My favorite SFS segment lengths are 10-20-10. The 20-meter float gives the athlete a nice period of grace before attacking the next sprint. Experienced athletes can progress into longer sprint segments or another set of float-sprint.

For jumpers, I like to cue “accelerate-sprint-runway speed-sprint” to describe the rep. For sprinters who have run the 400, “backstretch speed” can be substituted for “runway speed.” Both provide a nice union of practice and competition. For those having difficulty transitioning between the sprint and float, cueing arm action can be helpful. As they enter the float zone, instruct them to limit their arm action, and then when they enter the sprint zone, instruct them to expand arm action.

Placement of SFS sessions would be in max-velocity sessions or possibly speed-endurance sessions. They are neurologically demanding and may require additional recovery time. Novice athletes should have a foundation of fly work and competition experience before using SFS. You can also tier sessions: Young athletes in the program can just complete an acceleration and sprint, while seasoned athletes can complete the full SFS.

The Home Stretch

“Be curious, not judgmental” is a Walt Whitman quote that I was reminded of while watching the television show Ted Lasso. It is one of my favorites, and one I need to revisit often. I think I excel in the first part of the quote, but I am a work in progress with the second. (My opening to this article could have been viewed as casting stones.)

There is room for debate among those of us who believe in sprinting as a quality stimulus. We must not let judgment get in the way of our curiosity, says @HFJumps. Share on XThere is room for debate among those of us who believe in sprinting as a quality stimulus. We must not let judgment get in the way of our curiosity, so we can serve the athletes in front of us in the best manner possible.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

Great article Coach…lots of pearls of wisdom. I love the concept of controllable sprinting on the runway instead of maximal. I have been very guilty of max speed on the runway.

Quick question…are most of your practices on the runway shorter approach jumps? Save the full approaches for competition? But for securing marks on the runway, are you measuring on the track and transferring to the runway? Hope that makes sense. I often think my athletes spend too much time at the pit and I am guilty also of allowing too many full approaches.

Thanks!