Training the phosphagen system via sprinting was the focus of my article on Field and Court Sport Training from a Track Coach’s Perspective: The Phosphagen System. I spend a lot of time discussing the benefits of sprinting because one of the few absolutes I believe when training athletes is that: In land-based sports which involve A to B movement, if training at maximum speed is not addressed, there is a gaping hole in the training program. The degree to which athletes sprint should be based on the demands of the sport (and more specifically, the demands of the position/event, if applicable). For example, a wide receiver in football should sprint more than an interior lineman, but the bottom line is that both players should be exposed to it.

“The truth is most team sport coaches have no idea how to develop speed, so they obsess over playbooks and schemes to compensate.” 1

In reversing this situation, if I coached badminton (a sport I’ve only played recreationally), I would initially focus on coaching what I am comfortable with: developing speed, strength, power, and agility. As the years progressed, I would become more familiar with the technical and tactical requirements of the sport and would blend them into my coaching.

I wonder if field/court (FC) coaches invest enough time into learning what it takes to develop speed. I have written in the past that an athlete with a low training age can undergo just about any type of training and improvements in speed will occur, but just because improvements occur does not mean the training is optimal. The choice to implement true maximum speed sessions is a start; the ability to conduct those sessions in the most effective manner possible is a never-ending quest.

Since the benefits of maximum speed training can be best realized through true maximum efforts, it is important for the athlete to feel great heading into the session. Therefore, I strongly suggest setting up training around maximum speed/effort days. Although there are always outside variables to take into account, a coach can at least set up days in which the athlete should be fresh.

“Speed development must be set up before you begin any type of endurance training. Speed is 25 times more difficult than endurance to develop.” 2

If speed is 25 times more difficult to develop, coaches should make all efforts to ensure that they conduct maximum speed/effort sessions at the highest quality possible. Once these days become the centerpiece of the training structure, everything else falls into place. This takes us to addressing the glycolytic and aerobic energy systems.

A New Perspective on the Glycolytic System

Training the glycolytic system asks the athlete to perform max effort work bouts with incomplete rest. These bouts are often done until failure (when the athlete reaches a tolerance limit). Workouts such as these have value, but only if used appropriately. If I was an athletic director, the following would be grounds for dismissal:

- Athletes completing intense glycolytic workouts twice in a day. This occurs often in the early season of many FC sports during two-a-days.

- Athletes completing intense glycolytic workouts on back-to-back days. This is common between FC sport competitions.

- Athletes completing a maximum speed workout the day after an intense glycolytic workout. How can an athlete attain their true max speed if their bodies are fried from the previous day? I do not see this occurring often because those who properly use maximum speed sessions know this would be far from ideal.

In order for intense glycolytic training to have value, the body needs to be given a chance to rest so it can grow. In the book, Peak Performance, a key concept is the equation: Stress + Rest = Growth.3 Much like American society as a whole, many coaches are phenomenal at piling on stress, but fail to give adequate rest, which inhibits the ability to grow. Coaches should give athletes at least 48 hours between intense glycolytic workouts where the recovery is complete rest (a day off) or light aerobic activity. For FC sports, a general guideline is to train the glycolytic system once or twice per week. Competitions count towards the total.

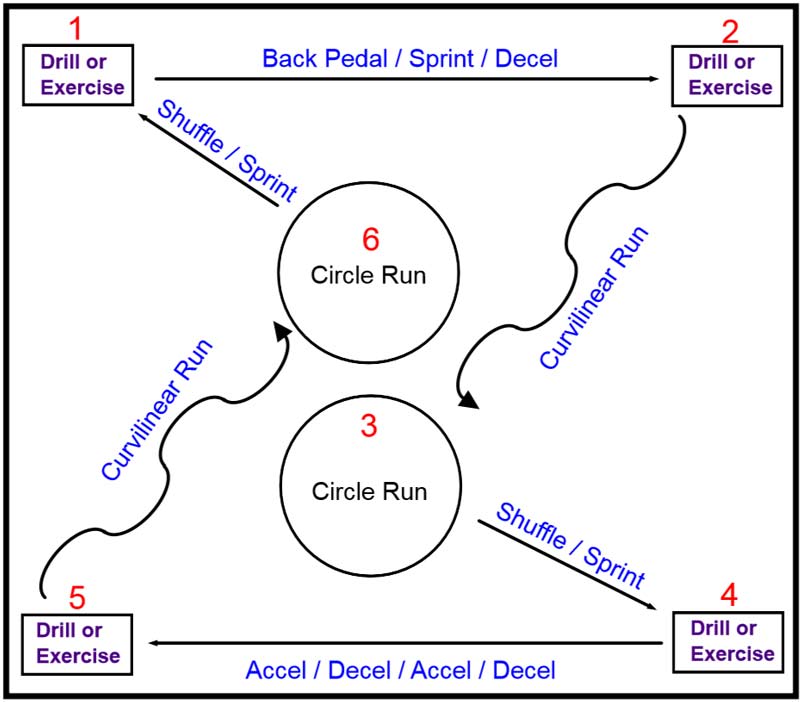

For intense #glycolytic training to have value, the body needs to be given a rest so it can grow, says @HFJumps. Share on XGlycolytic sessions give coaches a chance to be creative. As a track and field coach, I implement general technical and event specific work that eventually blends into the intense glycolytic workout. The possibilities are endless. From an FC sport perspective, I would encourage a variety of activities such as the circuit below.

For many FC coaches, training the glycolytic system is like what Baby Bear’s things are to Goldilocks—just right. From their perspective, training the phosphagen system via sprinting does not make an athlete tired, so it has no value because FC athletes are tired during competition. On the other end, training the aerobic system is not intense enough, so it does not transfer to gameplay where intensity is higher. Much of this is dogmatic in nature: coaches are doing what was done to them because it is all they know. However, living in the middle is not ideal in this case.

“If this (glycolytic) is the only method of training, the athlete will have a disproportional glycolytic energy system compared to his oxidative (aerobic) and ATP/Cr-P (phosphagen) energy systems and optimal performance will not be possible.” 4

Optimization should always be the target, and for this to happen, there needs to be balance among the three energy systems. With this being said, the balance is different for different FC sports. Due to the play length and start/stop nature of football, the glycolytic system is not required as much as it is in soccer or basketball (and its amount of use even in these sports is lower than most people think).

The Glycolytic System and ‘The Grind’

Coaches tend to view glycolytic workouts as the most challenging, and for good reason. There is no doubt extreme discomfort happens when acidosis occurs during intense exercise and immediately thereafter. Due to this extreme response, many coaches associate it with putting in quality work, and feel the need to achieve acidosis more than is necessary. This leads them to think they are outworking their opponents, and the badge they give themselves helps create a culture that embraces “the grind.”

When I hear the term “grind” when discussing training, I cringe. I understand it refers to training hard, but in my eyes, it casts a negative light on the training environment I want my athletes to experience. If an athlete is “grinding” in a training session, he or she is in a survival mindset. This means the focus becomes how to get through the workout, not how to have the best workout possible.

Coaches should do everything in their power to ensure an athlete’s mindset prior to a workout is positive, especially on days that pose a significant challenge. I cannot overstate the importance of the words and actions of a coach prior to these sessions. The athlete’s pre-workout perspective can determine whether the workout will be successful. Which statement would you rather have your athlete say?

“I am going to dominate this difficult workout.”

“I am going to grind through this difficult workout.”

Or maybe a better question is, do you prefer your athletes in survival mode or performance mode?

Being in a perpetual “grinding” training environment is like being the parent of a newborn. This often represents an extended period of an inconsistent sleep-wake cycle. The lower volume and broken nature of sleep leads to greater stress. Couple that with having to try to soothe a baby for an extended time multiple times per day/night, and you have a person who is in survival mode.

Athletes who are always in the grind consistently operate at a level below their capabilities, says @HFJumps. Share on XAs that time progresses, it becomes the person’s new normal. He or she learns how to operate at a submaximal level. Then, a crazy thing happens. The infant (and consequently, the parent) starts to sleep through the night. Stress levels begin to decline. The parent begins to feel great again and wonders how the heck he or she operated during the previous six months.

Athletes who are always in the grind consistently operate at a level below their capabilities. If winning games is the primary objective in FC sports, I would do everything in my power to ensure athletes feel optimal heading into competition. When athletes come out of a grinding atmosphere and take part in a program that manages training stress effectively, they tend to flourish. They also learn that feeling awful after every workout is not necessary for growth to occur.

Grinders and Volume

Grinders also tend to obsess about volume. I have had numerous conversations with FC sport coaches where I have outlined ways to improve maximum speed. I advise them to do the following on a maximum speed/effort day:

- Get the athletes ready to operate at maximum intensity.

- Have them sprint 40 meters, three to five times, with full recovery between reps.

- Send them home or do similar plyometric and weight room activities (high intensity, low volume, full recovery between work bouts).

When I ask them how the workout went the next day, they typically say, “It was great, we did it all, and then we finished the workout with suicides to get some work in.” My head nearly explodes each time I hear this. Volume IS NOT the only way to “get work in.” Novice coaches think in terms of volume only, while skilled coaches manage volume, intensity, and density to maximize adaptation.

Glycolysis and Lactate

Before moving on to the aerobic system, I will cover one other consideration regarding the glycolytic system. A product of glycolysis is lactate. Lactate has numerous roles in the body, one of which is as an anabolic agent.5,6 This concept was addressed on the Just Fly Performance Podcast #14:

“I am always looking for opportunities to subject my athletes to lactate in mild to moderate doses. In an acceleration development workout, if you hit the recoveries right, you’re getting speed and power development and restoration, all in one nice, tight package. It’s like your birthday; it’s all there for you.” 7

I love this quote because it is a great reminder that, even though a particular workout may focus on addressing a particular energy system, a coordinated effort between the three exists at all times. Acceleration development workouts zero in on the phosphagen system, but glycolysis still occurs, and athletes can reap the restorative rewards of lactate in a well-constructed session. This can also be done in the weight room or on the field/court by managing work/rest ratios. The key is for lactate accumulation to not impact the power output. Here are some options:

- Acceleration development usually consists of maximum effort for 30 meters, or four seconds or less (coaches can extend the time slightly if athletes use weighted push/pulls). In the previous article, I stated one minute of recovery should be used for every 10 meters when the goal is attaining maximum speed (usually sprints longer than 30 meters). In acceleration work, however, this could be cut to 30-45 seconds per 10 meters to accumulate lactate. Coaches can get close to locking in an appropriate rest interval with the use of an electronic timing system such as Freelap. If the time rises higher than 5% of that day’s best time, power outputs could be declining and rest intervals should be extended (or the workout should be stopped).

- In the weight room, coaches could extend rep ranges to get a slight dip into the glycolytic zone (work set length of approximately 7-15 seconds). Putting a group of three in a rack generally times the rest interval perfectly.7

- Bodyweight/medicine ball circuits. The work/rest ratio would depend on the exercises.

- Coaches can also cover this on the field or court by addressing game tactics. Small-sided games are a great option. Again, work/rest ratio would be at the coach’s discretion based on the nature of the small-sided game.

It is important that coaches do not take this section out of context. Just because there are anabolic effects of lactate, it does not mean the coach should blast their athletes with intense glycolytic work every day to get a higher anabolic effect. Too much glycolytic work can impair nervous system function, which decreases power output.7 This puts the athlete in a sub-optimal state.

In summary, intense glycolytic workouts (competitions included) should rarely exceed two times per week. Coaches can look for opportunities to create mild to moderate lactate during workouts where the focus is the phosphagen or aerobic system.

The Aerobic System and Repeat Sprint Ability (RSA)

Field and court sports tax athlete’s RSA much more than track and field does. The overall intent of training for FC sports should be to get athletes to produce the highest number of maximum efforts possible. Maximum effort is a tricky phrase. When used, I mean the athlete is operating at or near 100% of their capability. No matter at what level of fatigue an athlete resides, they can always give a maximum effort. I prefer to have athletes who can give a maximum effort that is as close to what they are capable of as often as possible.

No matter at what level of #fatigue an athlete resides, they can always give a maximum effort, says @HFJumps. Share on XWhat gets overlooked with RSA is its large dependence on the efficiency of the athlete’s aerobic system. Aerobic training often gets a bad rap. People my age often associate it with VHS tapes of Jane Fonda and Richard Simmons taking viewers through some killer cardio. There is obviously not much of a connection between this and FC sports. Fortunately, you can address the aerobic qualities needed for FC sports in a short training block and fluorescent spandex suits are not a requirement. The following information showcases the importance of the aerobic system and gives some methodology of how to improve it.

An example of twins who had the following resting heart rates (RHR), lactate thresholds (LT), and functional reserve ranges (FRR) is shown below.8 All are measured in beats per minute (bpm). FRR is found by subtracting RHR and LT.

FRR can be increased by lowering RHR or increasing LT. Both can be done by training the aerobic system. All systems (even the phosphagen) recover faster in an athlete with a better aerobic system.8

A sink analogy can explain this. As the athlete performs physical activity, the “sink” fills up with metabolites. The aerobic system represents the drain of the sink. The bigger the drain, the better the athlete will be able to deal with, and recover from, an activity’s stress.4

Many people associate aerobic training with long slow distance running. Although it is an option, it is certainly not ideal for athletes involved in power sports. Here is a series of online presentations that give specifics of training the aerobic system. Within these, there are five different workouts. Parameters addressed include keeping heart rate between 110 bpm and 170 bpm (below LT), and training the system in two-week blocks (which is ideal for pre-season or early season focus).8 If a coach notices aerobic qualities diminishing over the course of a season, he or she can address them again in training.

Questions to Guide Weekly Design

FC coaches committed to their craft are meticulous planners. Offensive/defensive scripts and game situations are constructed during practice to give athletes a preview of what they may face during competition. Track coaches are also very detailed in their practice design. Many create elaborate periodization templates that outline the entire season.

I find these templates to be helpful reminders of what the focus should be during the season, but I also have learned that coaching what is in front of me reigns supreme in program design. This is the reason I wait until the end of the week to plan the next week’s workouts. Below is a list of questions I work through that allow me to build the best possible training scenario each week.

- What are the goals/themes for the next day(s), week(s), month(s)?

- How demanding was the previous day(s)/week(s)?

- How have the athletes responded to the previous training?

- How do I expect athletes to feel coming into the week?

- Are there competitions during the week?

- What are the expected demands for each athlete in the competition(s)?

- How will the training differ for athletes with different demands in competition?

- Is the weather conducive to the type of training desired?

- What facilities are available?

- Are there any notable outside stressors present (school, social) and, if so, what adjustments should be made?

- If an athlete cannot complete the desired workout, what contingencies can still address the desired training effect?

Final Remarks

I tailored the content covered in this article towards the design of FC sport training when viewed through a track coach’s lens. Training structures and methods specific to the body’s energy systems dominated the information, and I included both items to incorporate and to avoid.

My hope is that FC coaches will evaluate their current programming and see if there are areas they can tweak. From there, they can decide how best to address this information based on their current practice/conditioning structure, as well as the physical demands and skill required for athletes to be successful in their sport.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

- Thomas, Latif. (via @latif_thomas). “The truth is most team sport coaches have no idea how to develop speed, so they obsess over playbooks and schemes to compensate.” 10:19 a.m. October 26, 2017.

- Veney, Tony. “Top 6 Hurdle Training Parameters.” Complete Track and Field. July 30, 2013.

- Stulberg, Brad and Steve Magness. Peak Performance. New York: Rodale, 2017. 27.

- Van Dyke, Matt and Cal Dietz. Triphasic Lacrosse Training Manual. Denver: Van Dyke Strength LLC. 2016. 49-60.

- Nalbandian, Minas and Masaki, Takeda M. “Lactate as a Signaling Molecule that Regulates Exercise-Induced Adaptations.” Biology. 2016; 5(4): 38.

- Godfrey, R.J., Madgwick, Z., and Whyte, G.P. “The Exercise-induced Growth Hormone Response in Athletes.” Sports Med.2003; 33(8): 599-613

- Schexnayder, Boo. “Just Fly Performance Podcast Episode #14: Boo Schexnayder.” Just Fly Sports, September 7, 2016.

- Dietz, Cal. “Triphasic Training System Aerobic Concepts Part 1.” Online PowerPoint presentation. June 25, 2017.