Scene 1: A coffee shop near you finds two veteran college track and field coaches beginning a conversation about their approach to off-season sprint training. One advocates minimum effective dose (referred to as MIN). The other has similar ideas regarding the importance of sprinting in training but views it through the lens of the maximum effective dose (referred to as MAX).

MAX: How many times per week do your athletes sprint in the off-season?

MIN: Typically two.

MAX: Can you lay out the general parameters for those sprint sessions?

MIN: Sure. The first sprint session of the week is acceleration-based and consists of 10 m to 30 m sprints for a total volume of 100 m to 160 m. The second sprint session focuses on maximum velocity and consists of 40 m to 60 m sprints with the last 10 m to 30 m timed. For example, in a 40 m sprint, we only time from 30 m to 40 m. For a 50 m sprint, we time the last two 10 m segments (30 m to 40 m and 40 m to 50 m). Athletes complete between three and four repetitions.

MAX: When do these sessions occur?

MIN: Usually either Monday and Thursday or Tuesday and Friday to ensure the nervous system is prepped for maximum intensity.

MAX: We used to do something similar. Let me ask you this, what is the most important factor in training a sprinter?

MIN: Developing maximum velocity. Ideally, I want it to occur later in a race. And even though I’m aware it only occurs at one moment in time during a race, I’d like to think through training we can widen the window of how long we can maintain the values close to maximum velocity.

MAX: I couldn’t agree more! I love targeting maximum velocity in training because it checks so many boxes. Huge forces in minimal time on one leg, acceleration development, maximum velocity development, along with the endocrine response post-workout. So in your off-season sessions, how much exposure to maximum velocity do your sprinters get?

MIN: Well, we know from timing 10 m segments that our men reach maximum velocity between 40 m to 60 m. So while they’re probably close to maximum velocity during some of our acceleration sessions (sprints <30 m), they’re not getting any exposure then. That leaves the maximum velocity day where I’d say they get between 40 m to 80 m of time spent at, or very near, maximum velocity.

MAX: Since you believe maximum velocity is the most important component of developing a sprinter, do you find value in safely increasing the amount of time your sprinters spend there?

MIN: Of course, but there would be risks in reaching it more often. What would you propose?

MAX: How many weeks do you have in your off-season?

MIN: Twelve.

MAX: Okay, let’s discuss your athletes who have two years of experience with you. I assume that heading into their third off-season, you would start with 10 m flys and progress up to 30 m flys.

MIN: Yes. Assuming ideal progress, four weeks of 10 m flys, four weeks of 20 m flys, and four weeks of 30 m flys. We would cap the 10 m and 20 m flys at four repetitions and the 30 m flys at three repetitions.

MAX: Sounds like a reasonable progression. Before I move on to a plan, can we agree on the following parameters?

- Although it is not perfect, let’s assume that the length of the fly portion represents the distance an athlete spends at, or very close to, maximum velocity.

- Maximum velocity is 97% or better of an athlete’s best split. (Author’s note: an athlete with a 10 m fly best of 1.0 second is considered to be at maximum velocity for anything 1.03 seconds and under).

MIN: Yes.

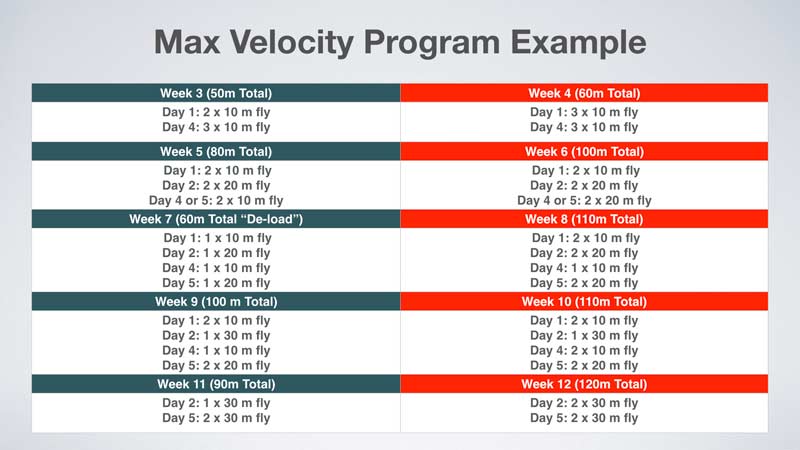

MAX: Okay. With these in mind, your athletes would attain the following maximum velocity totals each week during the 12 weeks:

- Weeks 1-2: 30 m (3 reps of 10 m flys)

- Weeks 3-4: 40 m (4 reps of 10 m flys)

- Weeks 5-6: 60 m (3 reps of 20 m flys)

- Weeks 7-8: 80 m (4 reps of 20 m flys)

- Weeks 9-12: 90 m (3 reps of 30 m flys)

The overall total would be 780 m spent at maximum velocity.

MIN: Yes.

MAX: Okay, here is my proposal. Keep the first two weeks the same. That’s a total 60 m at maximum velocity during the two weeks.

MIN: Works for me.

MAX (begins scribbling on a napkin): Here are the following weeks:

Time spent at maximum velocity totals up to 940 m, which is 160 m more than your current programming.

MIN: Apparently, you believe athletes can handle sprinting more often than many would consider possible.

MAX: That’s true. But notice that the load placed on them each day is smaller than what you’d call for within a maximum velocity session. In essence, I want to have a low daily volume, which will allow for more frequent training, leading to a higher weekly volume.

MIN: Interesting. How do you measure athlete preparedness?

MAX: Heart rate variability measures are ideal, but we don’t have access to a system. We’ve had success using simple tap tests, conversing with athletes before and early on in practice, and paying extremely close attention to how they warm-up. We’ve also found that, because their performance is measured more often, they’re much more likely to take care of the “other 22 hours” away from training.

MIN: What do you do during the other training days?

MAX: Anything that won’t impact the performance on the days listed. You have the chance to be creative with each individual on these days. Technique work is common, general circuits, lifting, etc.; the list certainly goes on. The main idea is to prioritize improving maximum velocity during this phase—anything else done on other days should support this priority.

MIN: What if an athlete is unprepared to sprint on one of the days?

MAX: We adjust, of course. Having contingency training plans is essential to maximizing athlete development. We have a wide array of activities on our training menu that mesh well with sprinting. Through conversation and physical assessment of the athlete (if necessary), we can determine which route is the most appropriate.

MIN: Well, you certainly have given me something to think about. Can I have that napkin?

MAX: Excellent and absolutely! Remember, if maximum velocity is king and we have access to it, why spend time messing around with lesser modalities?

End Scene 1

Scene 2: We find our two favorite track coaches, MAX and MIN, in the midst of a conversation at the same coffee shop five years later. The only difference is MAX has quite a bit more gray hair and MIN has cultivated an exquisite mustache. The two have not spoken since their meeting five years ago.

MAX: I’ve noticed your program has had some incredible performances over the past few years. Did it have anything to do with our earlier conversation?

MIN: Our conversation led me down a road of reflection. I was satisfied with our programming. It was effective, and our athletes were happy and healthy; my focus was just on bringing my best to each session. When I assessed your proposed plan, I concluded that the only way I could offer a solid critique was to put it to the test. For two years, we did exactly what you laid out during the off-season. Our athletes loved it, and we experienced better gains than we had in years past. More than anything, however, our conversation reminded me that complacency has no place in our profession. Our conversation caused an initial change, but it also served as a springboard to even more change in our programming.

MAX: How so?

MIN: I’m glad you asked. I have the entire layout with me, but before I show you, I should point out that I based it on two items: increasing the time spent at maximum velocity and working around the concept of intent and intensity. (Author’s note: hat tip to Coach Gabe Sanders who eloquently explained the intent versus intensity concept at Track Football Consortium 8; I had been milling through a much more complicated explanation in my head for years, but he boiled it down to a three-word phrase.)

MAX: What do you mean by intent and intensity?

MIN: During your max velocity sessions, would you say your athletes have high intent?

MAX: Absolutely! They’re always on a quest for a new best!

MIN: When you perform your sessions, are they always on a track surface with spikes?

MAX: Yes.

MIN: Spiked up, on a track, and timed is one way to achieve both maximum intent and intensity.

MAX: Are there others?

MIN: In regards to intent, yes—timing, racing, and chasing-eluding. The beauty is timing can accompany both racing and chasing-eluding.

MAX: I understand racing. We often progress to completing our fly sprints with competition. We go up to four athletes at once, and each receives a time. I have an idea of what you mean by chasing and eluding, but can you give me an example?

MIN (pulling out cell phone): Sure.

Video 1. When sprinting around curves, athletes demonstrate maximum intent. The curves also automatically lower the intensity compared to a straight-line sprint.

MAX: No doubt, the pool noodle adds a little more incentive! A great way to raise intent! I noticed they were kind of…..swerving? Could you elaborate?

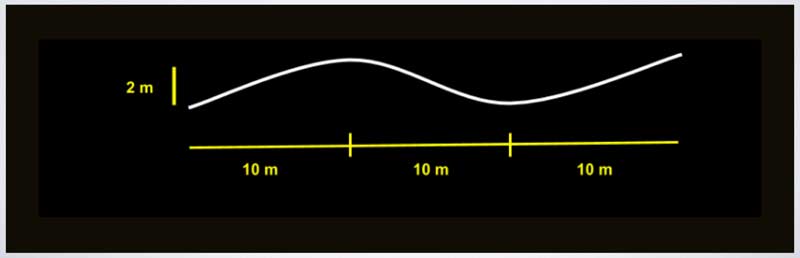

MIN: After our conversation, I was on a quest to chase infinite speed on the straightaway, and there is still no question it’s our priority. However, I kept coming across content involving the benefits of curvilinear running. After doing research, I decided it would have value in our training design.

In one study I found, sprinters performed approximately 8.9% slower when they sprinted a 40 m curve with a 17.2 m radius (the recommended minimum for a 200 m indoor track) when compared with a straight 40 m sprint. I thought, What if I incorporate multiple curves in a single repetition which have a larger radius?

First, it creates a more robust runner by continually changing the force vectors the athlete puts into the ground. Second, it does a nice job preparing our athletes for the treacherous curves they face on an unbanked indoor track. Finally, and possibly most important, having a larger radius allows athletes to reach higher velocity. If they are 8.9% slower on a 17.2 m radius, I thought we could get to under 5% slower with a larger radius. It’s a challenge to achieve great accuracy in timing multiple bends, but the eye test shows some of our athletes can get fairly close to maximum velocity. Three birds, one stone!

MAX: The video showcases maximum intent, and the curves automatically knock down the intensity when compared with a straight-line sprint.

MIN: Exactly.

MAX: Brilliant. What other factors influence intensity?

MIN: Weather—temperature, wind, and even humidity. We get outside any chance we can, but there is something to be said for a controlled indoor environment when assessing athlete progress. Beyond that, footwear and surface play a big role. We did some of our sessions on field turf, grass, indoor and outdoor track surfaces, and indoor courts. Our athletes fluctuated between training shoes, racing flats, and track spikes. We determined the intensity desired and created the combination of surface and footwear that would match.

MAX: Interesting. Can you show me the program now?

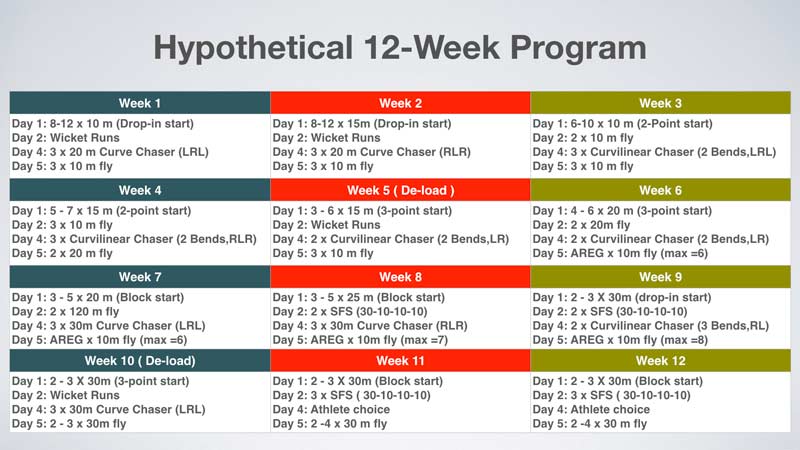

MIN (taking out papers from his backpack): Yes, sir. First, here is the focus of each day.

Day 1. Acceleration

Day 2. Maximum Velocity—Fly Sprints and Sprint-Float-Sprints (SFS)

- Four numbers follow SFS. For example, 30-10-10-10 means Accelerate 30m-Sprint 10m-Float 10m-Sprint 10m. Additional information can be found here.

Day 3. Curved Sprints

Day 4. Maximum Velocity—Fly Sprints and Auto Regulation (AREG) Fly Sprints

- AREG: An athlete performs up to the max number of reps assuming they are within 3-5% of their best time. An athlete with a 10 m fly best of 1.0 would complete reps up to the max as long as they do not run above 1.03 seconds (3% cutoff). Additional information can be found here.

MIN: And here is the actual program.

Key for Table 2

Drop-in start. Athlete skips into a start. Because it’s less demanding than a static start, more volume is possible.

Wicket runs. Also referred to as mini-hurdle runs. Build-up distance, hurdle spacing, and surface selection vary on the session’s objectives, constraints on the session (such as weather), and athlete needs. We determine footwear by the surface and spacing. The number of hurdles typically range from 8-16.

- Build-up: 10 m – 30 m

- Hurdle Spacing: 1.4 m – 2.2 m

- Surface Selection: Grass, field turf, indoor/outdoor track, indoor court

Curve chaser. A sprint on the curve of an indoor/outdoor track or a curve on a field or court sport surface.

Curvilinear chaser. A possible 2-bend setup is offered below. The first L in LRL means the athletes move to the left first in the first rep. The R means the athletes move to the right first in the second rep.

Athlete choice. Athletes have the flexibility to choose what they feel will prepare them to run their best series of 30 m flys the following day.

MAX: Wow. I have a few questions.

MIN: Shoot.

MAX: I see you included sprint-float-sprints. What have you noticed using them?

MIN: With the 30-10-10-10 setup, many athletes will have their fastest 10 m during the float. It’s a challenge determining the reason for this. Many athletes could have built up to their maximum velocity during this section (40 m – 50 m), and therefore hit their best time even though they’re taking the foot off the gas during the float. Other athletes may be faster during this section because it’s the first time they stopped “forcing” speed. Regardless, I see the coordinative challenge of invisibly shifting gears as a benefit for all of our athletes.

When we get to the 30-10-20-10 repetitions, we begin to see athletes who can hit similar times at or near their 10 m fly bests in the two 10 m sprint sections. It’s argued that the 20 m float section gives the nervous system time to recoup and put forth a second great effort. It also fits the goal of trying to maximize the time spent at or near maximum velocity.

MAX: It sure does! Can you tell me about your experience with AREG?

MIN: A couple of years after our conversation, I stumbled upon the concept and thought it would be a way to once again maximize time spent at maximum velocity. We’ve played around with the cutoff and usually assign a specific percentage to each individual. Most of our athletes are either 3% or 4%. Regarding repetitions, the average is between five and six. Some could certainly go above the maximum, but we have yet to determine if it’s necessary. We placed the workout at the end of the week because the athletes have two days off afterward. We encourage taking a nap right after the session on Friday and going for a long walk outside on Saturday and Sunday.

MAX: I love it. Get outside and ditch Fortnite! I notice you included a day of acceleration work, and we would both agree that athletes are not touching maximum velocity on those days. What is your reasoning?

MIN: First, athletes need repetition when developing acceleration. I agree acceleration development comes with training maximum velocity, but I didn’t want to give up so many opportunities to practice acceleration by extending the length of the repetition so the athlete could reach maximum velocity.

Then I came across a study which showed athletes who ran the 40-yard dash at the NFL Combine reached 93-96% of their maximum velocity 20 yards into the sprint. Could this vary with some of our track sprinters who have the ability to delay maximum velocity? Absolutely. It also led me to believe that, even in accelerations of 20 m to 30 m, we may very well touch on some maximum velocity qualities.

MAX: Well, now you’ve given me a lot to think about! Even though what you listed seems to be less maximum velocity training than what I laid out, your athletes may be getting more exposure! I need to snap some photos of these programs!

MIN: Go for it. See you in five years?

MAX: Maybe we should Skype once a month?

MIN: Nobody’s got time for that.

MAX: Truth.

End Scene 2

Final Thoughts

In conversations with most sprint coaches, I’ve found that many believe they can do true sprinting only two or three times per week. The program I’m in follows this philosophy. I’ve wondered, however, if we could prepare our athletes properly and manage them appropriately during a phase in which sprinting occurs 4-6 times per week, would this higher density yield better results?

If we prepare & manage athletes properly so sprinting occurred 4-6 times a week, would this higher density yield better results? says @HFJumps. Share on XI’d love to prescribe a 4- to 6-week phase following the same guidelines as the somewhat random hypotheticals presented above. Unfortunately, our state regulations would not allow something like this to occur in our off-season. Once our season is underway, competition and event-specific work would make the picture much more cloudy.

Training ultimately comes down to stress, and the body will adapt to it when received in appropriate doses. The training blocks listed may be a bit of a reach, but an off-season could be a perfect spot for it. Let’s take a look at a simpler hypothetical with an athlete who can follow one of these two programs with the given results:

- Program A: 3 x 10 m flys on two training days, all ran in 1.0 seconds

- Program B: 2 x 10 m flys on five training days, all ran in 1.0 seconds

Which program would lead to a greater improvement in maximum velocity? Is there more value in the higher daily volume in Program A? Does the greater training density (and corresponding higher total volume) of Program B make it superior? Would a hybrid of the two programs be even better?

For any sprint coach, all these questions are worth pondering. It’s common to get caught up in accepted training dogma. We need to ask ourselves if the way it’s always been done is the way it should be done. I often refer to the phrase “there is nothing new under the sun” when it comes to training, and I’m a firm believer in it. However, our situations are all unique (clientele, facilities, equipment, weather, contact limitations). It’s our responsibility to try to find the best solution for our situation.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

Hi coach,

Are the workout programs that you listed purely hypothetical or have you done them and gotten results with them before? I’m pretty skeptical of doing this kind of programming over the standard two-three speed sessions per week programming but would be curious if there are any results showing that this way of training could potentially be better.

In my experience the body seems to recover better if there is a full recovery day or two between speed sessions than if it is made to do two speed days back to back albeit lower volume per session.

In my experience it’s the higher frequency and lower dose wich works for longer duration.

The body adapts (recovers) very well from short intense sessions. The stress level should neither be too low nor too high. It’s about preparedness. Strong focus and motivation are the requirement for an increase in performance.

TM,

Thank you for reading! We have dabbled in back-to-back high intensity sessions with no issues. Ultimately I think it comes down to the level of athlete you are working with and their ability to recover. My 5 year old can sprint everyday, someone running in the world championships may only be able to do so once every 10 days. I plan on writing a follow-up with a more detailed answer as I am getting a lot of the same questions. Thanks again!

Thanks for the reply. Yeah, what you are saying makes sense. A developing athlete who isn’t able to generate much speed would probably not have a problem sprinting everyday. I was thinking of it from the perspective of a world class sprinter who is running under 10 seconds for a 100m and who is very fast-twitch dominant.

To clarify my initial question: do you have experience using this kind of program for world class sprinters or was it only for developing athletes? I can buy that someone who is not running low 10seconds /sub 10 would not have issues training this way. I’m just skeptical if it would work as well as a minimum effective dose approach for an elite sprinter.

Looking forward to reading the follow-up.

Short answer….No, I do not have experience using this type of program with elites. No question the power they produce would make it much less likely they could rebound for another high intensity session the following day, even if the dosage is low. However, in championship meet situations, they need to access maximum intensity efforts and have the ability to recover in a short time period. I will go into greater detail in the follow-up.

Hey, how do you decide what timing the sprinter should achieve during the short sprint trainings. Is it based on his competition100mtr PB or we test the sprinter for the specific short distance trainings and decide?

In the Hypothetical 12-Week Program, posted by Coach “Min”, the amount of volume he proposes per workout day seems low compared to what I am doing now. Is that all his athletes do on the track (or grass) for those days? For example, Week 1/Day 1, he has “8 – 12 x 10m (drop-in starts)” So, besides the warm-up and cool-down — is that all the athletes do for that day?

I’m curious, because as a masters sprinter, my younger coach has me doing much more volume than the above workouts, and I am constantly battling inflammation and minor injuries.

That would be the on track workout. Whether it is paired with plyometrics, med ball throws, or WR activity is a bag of worms I didn’t want to open as it would have increased the permutations significantly.

My best advice is to listen to your body. If you are battling inflammation and nagging injuries, adjusting volume may be helpful. I’d also suggest looking into extreme isometrics.

Hi, RA,

Thank you for the article. I have a question based on an observations in the article it states, “…maximize time spent at maximum velocity. We’ve played around with the cutoff and usually assign a specific percentage to each individual. Most of our athletes are either 3% or 4%.“ I’ve seen the 3-4% cutoff in other places and I’ve used that principle to create a “training range.” Was that % determined based in trial and error?