[mashshare]

During my career, I have found the high jump to be the most difficult event to coach in track and field. Narrowing the discussion to the jumping events, three factors determine success in the long jump: takeoff speed, takeoff angle, and the height of center of mass at takeoff. The long jump also has the least technical demand. The triple jump depends on similar factors, and if a coach is patient, an athlete can progress through it with minimal technical issues. What makes the high jump a bigger challenge are the curved nature of the approach and the rotations that result because of it.

What makes the high jump a bigger challenge than the other jump events are the curved nature of the approach and the rotations that result because of it, says @HFJumps. Share on XBefore progressing, it is necessary to identify the immense influence Boo Schexnayder’s teachings have had on my development as a track coach and, in this specific case, training for the high jump. His resource, “The High Jump: Technique and Teaching,” is a must-own. I watch it before every season, and a new light bulb goes on in my head every single time. I also refer to my seven-page outline of this resource numerous times each year.

Along with the teaching of Coach Schexnayder and others, I’ve found developing the following essentials to be most effective for developing young high jumpers. Before we dig into those, however, I must first lay out some general groundwork:

-

- Anytime you see an asterisk (*), it means that you should refer to Coach Schexnayder’s high jump resource for further information.

- Most of our high jumpers utilize a 10-step approach, although I think you could make a solid argument for the use of eight steps. Ultimately, the approach length is about athlete comfort and strengths. In terms of step numbers moving forward, a 10-step approach is obviously 1–10. However, to remain consistent in communicating with all high jumpers, an eight-step approach is numbered 3–10.*

The Start

With high school athletes, I am an advocate of the crouch or rollover start.* I have a theory that athletes who are “elastic” favor the rollover method because of the movement prior to the first step, which allows them to utilize energy via the stretch-shortening cycle. I find that high jumpers gravitate to this method, and it makes sense, as the majority would be classified as elastic-based instead of strength-based. For example, if Ben Johnson and Andre De Grasse did any of the jumps, my guess is Johnson would prefer the crouch and De Grasse the rollover.

The start must be consistent. That’s why I prefer the rollover or crouch start over the run-in. There are more steps with the run-in, which increases the chance for variation, says @HFJumps. Share on XI am generally a laid-back person, but during the teaching and rehearsal of the start, I am extremely intense. The start is the place where novice athletes tend to be lazy in any of the jump approaches. Variation will occur in any approach, and the most consistent parts of the approach should be the beginning and the end. In reality, the end somewhat takes care of itself because the athlete will steer to where they feel comfortable taking off. The highest variation tends to reside in the middle, and in order to minimize that variation, the start must be consistent. This is why I prefer the rollover or crouch start as opposed to a run-in. With the run-in, there are more steps, and more steps increase the chance for variation.

General acceleration mechanics should be followed during the start and initial steps. I look for a gradual push to vertical posture during the first three steps in a 10-step approach. However, during various drills and runs away from the high jump runway, I challenge athletes to push to vertical in a wide variety of steps to challenge coordination and general awareness of posture.

Initiation of the Curve

Because of my personal experience in the event, I was well aware of the importance of running the curve and the resulting lean created, which is necessary for quality rotation over the bar. One of the most common problems for athletes is that they abandon their lean as they come closer to the bar. Early in my career, my focus for the lean was during steps 8–10 in the approach, but encouraging athletes to “stay in it” did not yield great results. It was not until I was primarily tasked with coaching jumpers that I finally took Gary Winkler’s advice and “looked upstream” in regard to this issue. By emphasizing a quality initiation of the curve and rehearsing it A LOT, you significantly increase an athlete’s ability to maintain the lean.

A common problem for high jumpers is abandoning their lean as they come closer to the bar. Address this by emphasizing a quality initiation of the curve and rehearsing it A LOT. Share on XAccording to Schexnayder, the transition to the curve should begin with a slight turn of the hips during push-off in step 4. Step 5 initiates the curve and should travel outside of the line of travel. This establishes the lean. Step 6 establishes the curve and should land back on the line of travel. Verbal emphasis and demonstrating to the athlete how to run a smooth curve and not a “post route” tend to help with the problem of cutting the curve during steps 5 and 6.*

The video below showcases a drill we use to practice curve initiation. We do it on the high jump runway, but the beauty of it is that you can complete it in any open space (such as a school cafeteria or hallway during the winter months). You can construct a practice curve with chalk or cones*, or you can use the center circle on a soccer field. I have 10-step-approach athletes run back five steps from the start of the curve to establish their starting mark, and we rehearse steps 6–10 depending on space. Objects can be placed in the necessary locations for athletes to simultaneously rehearse the shifting visual focus during the event.*

Video 1. Running a marked curve on the track and rehearsing the high jump approach.

Arm Action in the Curve

One common error I find with novice jumpers is a decrease in the range of motion of the limbs. In general, the range of the inner arm will be smaller than the outer arm during the curve, and this should seamlessly correspond with the contralateral leg to preserve proper timing. However, many jumpers shrink the range severely during steps 6–9. I have even seen jumpers whose arms are bent nearly 90 degrees and locked at their sides during this entire portion.

I am a “least intervention necessary” coach, so trying to find a successful verbal cue and providing visual feedback would be my first steps. A steady diet of circle runs, half circle runs, and serpentine runs (my favorite) utilizing the same cue would accompany this. I have recently found success with some athletes using mini barriers (mini hurdles, cones, etc.) during half circle runs and in the curve of a full approach (hat tip to fellow high school coach Kevin Ritter).

It is a challenge to do this with a large group during the full approach, as the barriers need to be moved from rep to rep, but it is doable with reference chalk marks and video after a jumper has rehearsed the approach enough to establish consistency during a session. The mini barriers pose a hazard to the feet, and the arm mechanics tend to open up.

Video 2. The center circle of a soccer field can be used with cones or mini-hurdles in curved running.

Video 3. Simulating the high jump approach on a curve with cones.

Lean into the Plant

Earlier, I mentioned failing to lean as a common error for beginning jumpers during the last few steps. I believe one of these four things cause it:

-

- The jumper abandons the lean because they are moving at a velocity they can’t handle. In this case, move the jumper’s starting mark forward and encourage them to be more “controlled” during the approach. I do not like to use the word “slower” because it tends to cause the jumper to accelerate uniformly and then slow down abruptly at the end. Nobody enjoys the result of a crossbar wedged into their back!

-

- The jumper has a fear of not being able to land in the pit. A steady diet of short approach jumps (possibly adding a ramp) may help instill confidence.

-

- The jumper is not comfortable in flight. Earlier this year, I almost smacked myself in the forehead when I heard Dan Pfaff speak about jumpers inhibiting their abilities due to their fear of flight. Because of this, they attempt to find a solution that will make flight feel safer, such as ceasing to lean inward. In their mind, this will make it more likely for them to land safely.

Simple popover drills may be just what novice high jumpers need to develop comfort with flight, says @HFJumps. Share on XI had sworn off drilling simple popovers because I felt there was not much connection to the actual event. However, despite all my creative interventions, I know the brain is an overprotective mother and will do whatever is necessary to keep the athlete safe. Popovers may be just what they need to develop comfort, and it makes sense to implement them in early season programming. I do not foresee this issue going away, due to the lack of free play and increase in specialization our youth are exposed to prior to high school. Unless something changes on this front, I expect the collective proprioception and coordination of adolescents to continue to decline. - The jumper failed to initiate the curve properly. It is hard to maintain a lean if you don’t do what is needed to create it. See the previous section.

- The jumper is not comfortable in flight. Earlier this year, I almost smacked myself in the forehead when I heard Dan Pfaff speak about jumpers inhibiting their abilities due to their fear of flight. Because of this, they attempt to find a solution that will make flight feel safer, such as ceasing to lean inward. In their mind, this will make it more likely for them to land safely.

-

- If you are still having difficulty getting a jumper to lean in all the way to the plant and be vertical at toe-off, video 4 below may be helpful. The bar in front provides a constraint that can help the jumper get into proper position.

Steering Ability

As much as we would like all approaches to be identical, they simply are not. A high jumper will find a way to steer to a “safe” takeoff spot, and if they do not, it is common to see them run through the plant and head back to the start (I rarely see this happen in the horizontal jumps). So, if they are going to steer to safety, why is it important to enhance steering ability?

Practicing steering with drills that have a higher degree of variability may help the jumper better focus on the ideal takeoff mark in competition, says @HFJumps. Share on XI view it as supplemental insurance. Practicing steering with drills that have a higher degree of variability may help the jumper better focus on the ideal takeoff mark in competition. In other words, the range where the jumper feels safe at takeoff should not be the standard for where takeoff should occur. A tighter window is desired. Steering drills are only limited by an individual’s creativity. Here are a few I use that you can close with an actual jump or a scissor kick.

-

-

- Start at a random spot and run into an attempt.

-

-

-

- Start at a predetermined or random spot and skip or run-run-jump into an attempt.*

-

-

-

- Insert 1–2 exaggerated bounds within the approach and complete an attempt.

-

-

-

- Start at the takeoff spot, run away from it on the curve, and turn back to run into the attempt on the coach’s clap. I brought this to the jumps after utilizing a similar version in coaching the hurdles. I call this “out and back on a clap.”

-

Video 4. The “out and back on a clap” drill used to further develop steering ability.

Note that these options are less than 10% of the jumping we do. Whether it is “normal” short or full approach work, novices get a high degree of variation on each attempt because they are novices. They need to practice decreasing the variation of their “normal” work by practicing “normal” work. You should use the “fancy” drills listed above sparingly. We often use them as a break in the monotony, as athletes tend to find their challenge enjoyable.

Approach Rhythm

A quality approach has a rhythm that gradually quickens. This implies that the jumper is gradually accelerating. There should be no abrupt changes in the tempo of ground contact. The most common error I see with approach rhythm in high jump at the high school level is starting out with a very fast tempo and slowing as the jumper progresses into takeoff. Increasing momentum does not exist in this scenario as the jumper is not gaining weight during an approach.

I do not have a magical answer to improving the rhythm in the approach other than demanding full engagement during approach rehearsal. It cannot be an aimless run, yet it is common to see this at any high school track meet. I purposely work with our horizontal group during a segment where our high jumpers work on approach rehearsal. During this time, I keep an eye on the high jumpers, making sure they show maximum intent. It is easy to be engaged when the coach is around, but, ultimately, they need to be held accountable as individuals.

We don’t just address rhythm during approach work in our jumping program. It is essential in almost everything we do, says @HFJumps. Share on XWe don’t just address rhythm during approach work in our program. It is essential in almost everything we do. I encourage readers to follow the work of Andreas Behm and Chris Parno, as they have great ideas for implementing rhythm into training sessions.

Curvilinear and Coordination Considerations

Absorbing and redirecting energy is paramount in any sport, and high jumpers must be able to do it on a curve. In regard to training, a simple way to prepare the foot-ankle complex to be able to handle these demands is to perform activities on curve(s). The intensity of each activity can be in line with the training theme for the day. Here is a compilation of activities that athletes can do on the bend:

Video 5. Depending on the day’s training focus, numerous exercises can be performed on a marked curve, including hops, gallops, bounds, skips for height, and run-run-jump patterns.

Video 6. I have yet to find an athlete who does not enjoy the curvilinear chaser. Solo runs using Freelap are another great option.

It is important to note that high jumpers should still do the linear version of these drills. On the flip side, I feel sprinters, hurdlers, and long/triple jumpers should perform the curvilinear version to enhance robustness and better handle the curve sprinting they will be exposed to!

I am always looking for ways to challenge an athlete’s coordination, and asking them to complete an attempt from the other side (conjugate jumps) does this really well. We start with short approaches and a scissor kick. As athletes develop comfort, they move back and may even attempt actual flops. The ratio of great to good side jumps (we don’t use the word “bad”) can be anywhere from 1:1 to 10:1, depending on the time of the season. There are health benefits to being more balanced, and it also serves as a way to identify athletes who may be successful in the triple jump!

Balanced Tendon Training

Over the years, I have had sprinters and hurdlers, as well as long and triple jumpers, who, although they weren’t feeling great physically heading into a competition, produced very good (sometimes phenomenal) results. I have never had this happen with a high jumper. The following is a consideration for all athletes, but maybe it carries more weight with high jumpers.

Developing tendon stiffness is a common goal of training that I hear about in a wide variety of sport circles. It makes sense. We see elite performers who barely bend and have ground contact times flirting with zero, yet they produce an almost unimaginable rebound off the ground. Therefore, we design training activities (sprinting, plyometrics, explosive lifts, etc.) that emphasize the development of this quality. I will be the first to admit I have probably gone too far on the spectrum with this in the past. Developing tendon stiffness should be balanced with enhancing tendon health. This podcast with Dr. Keith Baar helped me connect some dots in regard to this balance.

While we do want our athletes to bounce like Tigger, we must take into account that genetics play a big role in that ability. It is similar to the high school football coach who sees the huge and freakishly fast football players who make their living on Sunday and then wants to transform his athletes into them. The most common way is to attempt to get players to physically look the part by spending hours in the weight room, but that can happen at the expense of speed not coming along for the ride.

High jumpers tend to be at risk for tendinopathy due to the torsion involved in the event. By implementing activities that promote tendon health, athletes will have a better chance to feel their best, which will allow them to perform their best.

The Necessity of Triangulation

High school facilities are anything but consistent. Because of this, it is even more important to control the controllable. One way is to ensure an accurate starting mark. If your athletes don’t triangulate their approach, they open the door to more variability.

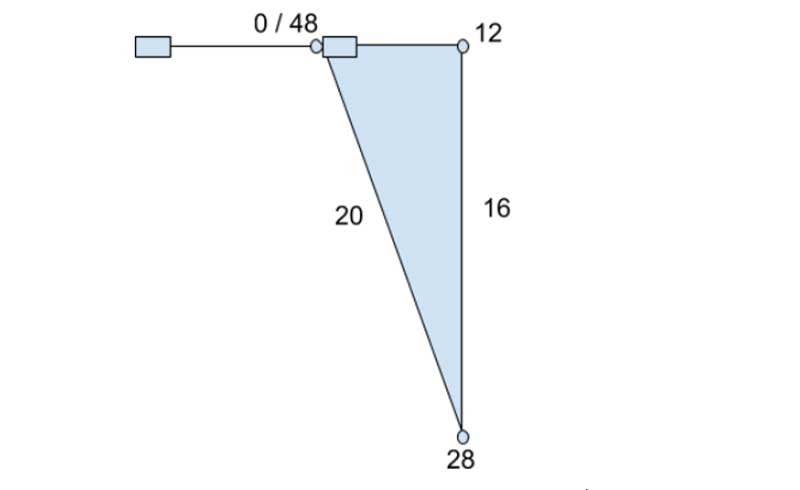

The image below shows two standards (rectangles) and a crossbar. An example of a possible triangulation (in feet) is given using the Pythagorean triple: 12, 16, 20. Many of our jumpers’ bottom check marks are 12 feet. Prior to competition, our athletes use this triangle to pull through to their top check mark (where they start).

One athlete holds the start of the tape AND 48 feet at the intersection of the crossbar and near standard. Another holds 12 feet directly out from the standard (bottom check mark). A third athlete holds the tape at 28 feet, forming a line perpendicular to the line out from the standard. Once the triangle is set with the tape measure taut, a piece of tape is placed at 12 feet and 28 feet. Then, each jumper can measure their distance back to their starting mark from the bottom check mark while ensuring the tape passes over the piece of tape at 28 feet.

-

- In addition, coaches and athletes should be sure that the line that they pull out from the standard to establish the bottom check mark is in line with the crossbar. In other words, the intersection of the crossbar with the far and near standard would be collinear to the bottom check mark if viewed from above.

An Emphasis on Consistency

While this article is far from a comprehensive guide to coaching the high jump, I hope it has emphasized the critical items needed for consistent jumping, and it has given some options to progress to in programming once you build a solid foundation. Above all else, remember to keep your high jumpers happy and healthy!

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

[mashshare]