SimpliFaster and Rude Rock Strength are excited to launch a new educational series that will feature specific athlete return to play (RTP) case studies. These modules will also cover our recent implementation of Hawkin Dynamics force plates into our RTP model and how this has influenced our programming and decision making. This series will run throughout the remainder of 2024 and cover a variety of specific injuries, athletes, and levels of sport.

If you missed our preliminary article, be sure to check out “The Philosophy, Art, and Science of Return to Play for S&C,” which covers the general framework and protocols for these modules to follow. This article will serve as a brief introduction to the full educational video module found below—we hope you enjoy and find value in this series.

Video 1. Module 1 Case Study: “High Ankle Sprain for Football.”

Athlete Background

This case study analyzes a current Division 1 football player (edge/defensive end) who suffered a high ankle sprain while tackling an opposing player in November 2023. The athlete subsequently had surgery in January 2024, in which a TightRope procedure was performed. The athlete followed standard rehabilitative procedures in accordance with his university for early phase rehabilitation. The initial intake and evaluation for this athlete occurred in mid-January 2024. This training intervention began two days after the athlete was permitted to be out of their boot. Thus, the athlete presented with significant pain, edema, and lack of function at the start of our intervention.

Injury Overview

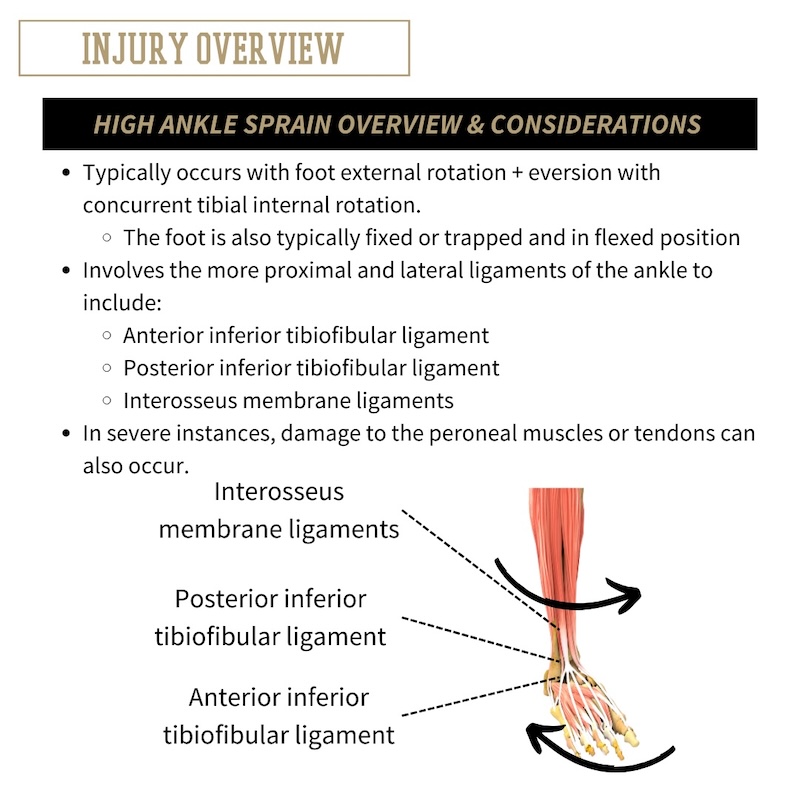

Ankle sprains represent one of the most common soft tissue injuries across all sports. Although high ankle sprains are not typically a devastating injury, they can be very difficult to fully recover from due to the mechanical demands of the foot-ankle complex. High ankle sprains can occur in a number of ways, but most often are a result of the foot being forcefully externally rotated while in a fixed or flexed position with concurrent tibial internal rotation. This results in damage primarily to the ligaments that support and attach the fibula to the tibia which include the posterior and inferior tibiofibular ligaments.

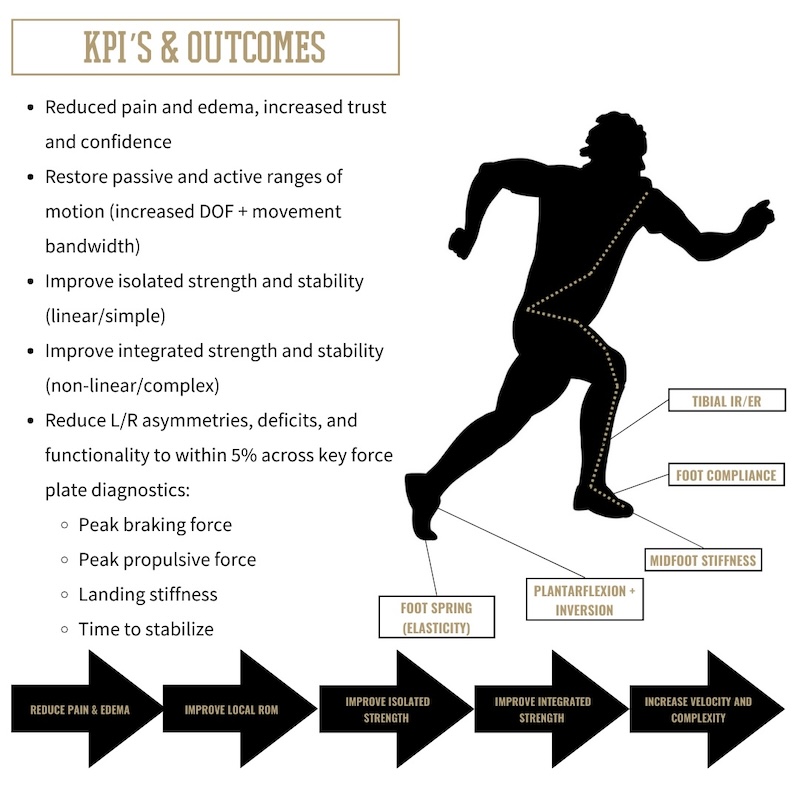

Additionally, high ankle sprains typically involve damage to the interosseous membrane, and in severe cases, can include damage to the peroneal muscles or tendons. The interosseous membrane is the connective tissue that is suspended between the fibular and tibial bones. The primary joint actions that are compromised from a high ankle sprain are tibial internal-external rotation, ankle plantarflexion, foot inversion-eversion, and foot supination-pronation. Considering the mechanics of the foot-ankle-lower leg complex, we also want to remain mindful of the stress that higher velocity and dynamic movements place on the injury site.

The consequential outcomes from a high ankle sprain can be abundant and wide reaching. Depending on the severity (grade) and whether surgery was required, these injuries can have a lengthy healing time. On average, athletes can expect a return to play timeline of about 6-12 weeks, but in most cases can be fully restored without any significant lingering or long-term effects. In more severe cases, surgical interventions may be warranted. In recent years, a new surgical procedure known as the “TightRope” procedure has become more commonly utilized and has seemingly shown promise in its effectiveness to promote long term stability and function of the ankle joint.

The consequential outcomes from a high ankle sprain can be abundant and wide reaching. Depending on the severity (grade) and whether surgery was required, these injuries can have a lengthy healing time, says @danny_ruderock. Share on XTesting Overview

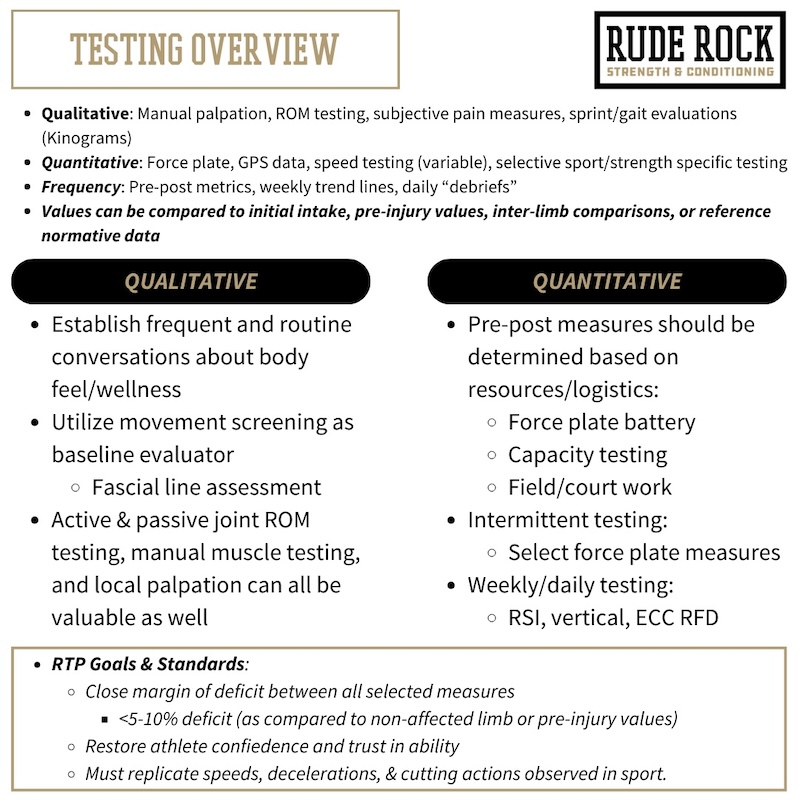

Both subjective and objective testing procedures are included in this RTP model. We utilize a combination of athlete intake (history/background), soft tissue assessment, and force plate testing for athlete evaluation and testing. The intake and histories give us the context of the individual—who they are as a human more so than who they are as an athlete. Histories provide a lot of information, but predominantly help to set firm boundaries, and understand what has and hasn’t worked for them to this point.

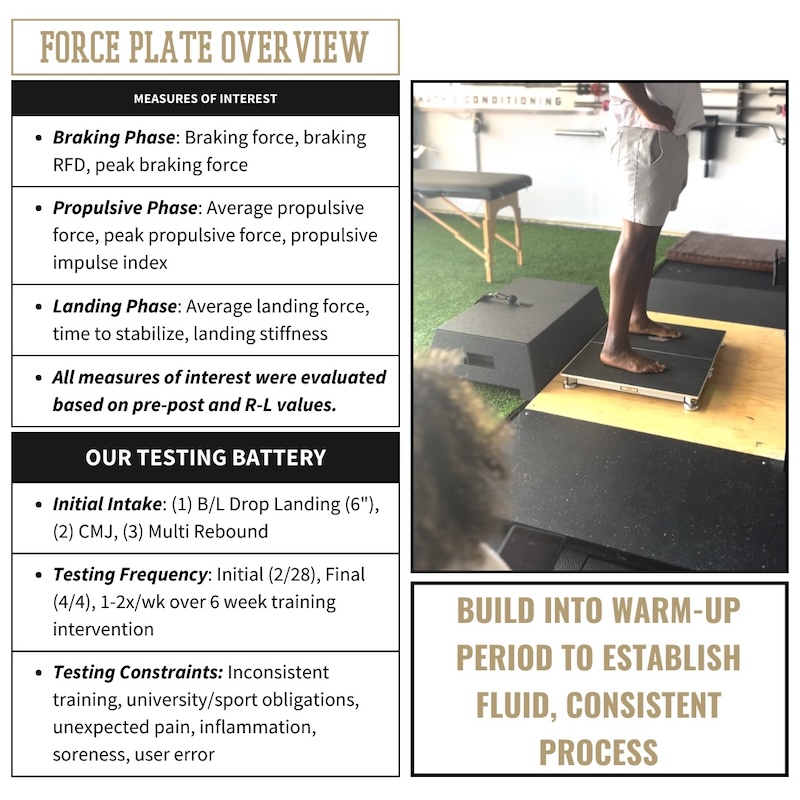

The two primary objective components we utilize include the soft tissue evaluation and force plate testing. The soft tissue component can be conducted in a number of ways and will largely be governed by your scope of practice. But even S&C coaches with no manual therapy background can get indirect evaluations of soft tissue function. This can be as simple as using passive range of motion (ROM) and global mobility assessments to evaluate soft tissue extensibility and sensorimotor acuity. The force plate testing provides us with the most concrete and determining point of evaluation that essentially confirms or validates our programming along the way. The force plate testing will be primarily influential for central training parameters like intensity, volume, and density. We also utilize force plate diagnostics to help determine more nuanced parameters such as tempo applications, load placement, and resistance type.

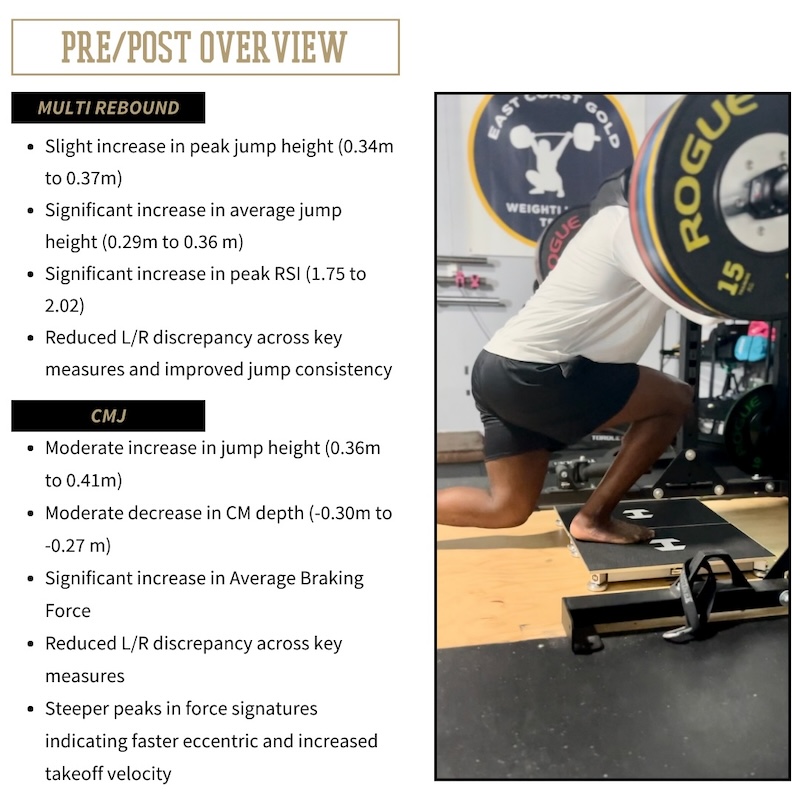

The force plate testing provides us with the most concrete and determining point of evaluation that essentially confirms or validates our programming along the way, says @danny_ruderock. Share on XWe utilize a general testing battery for data collection that includes the drop landing, countermovement jump (CMJ), and multi-rebound jump test. The specific metrics of interest (i.e., jump height, braking RFD, or peak propulsive impulse) can be variable depending on the athlete and context of their situation. For this athlete we emphasized jump height, countermovement depth, peak/average propulsive force, peak/average braking forces, and time to stabilize. As with any injury case, we also had particular interest in unilateral discrepancies across all primary measures.

This approach allows us to develop a triangulated understanding of who the athlete is, how the injury is affecting the soft tissue, and how their initial force profiles look. Collectively, across these pillars we can generate our performance KPI’s (shown below). Just as how the specific testing procedures and measures of interest are variable based on the athlete and context, the KPI’s are similar. A few of the primary factors for establishing KPI’s include what phase or point they are in the RTP process, what part of the sport calendar they are in, and what the expectations/demands are for that athlete.

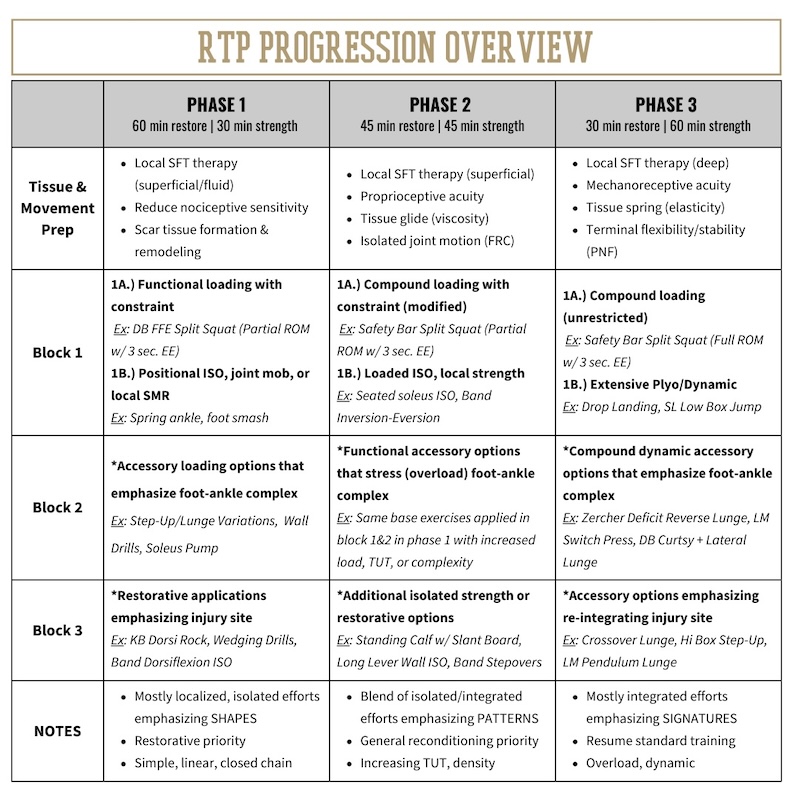

Training Overview

This case study was conducted over a six-week training intervention that included two 90-minute sessions per week. These sessions utilized a tandem approach of soft tissue therapy (restorative) and strength training applications. As we progress through the RTP phases, more emphasis is placed on the strength training and less on the soft tissue therapy side. The soft tissue restoration provides a supportive role to help manage tissue degradation, the strength training is where central adaptations are made. Importantly, this was performed concurrently to the standard protocols and treatment applied through the university. Although minimal information of what was being done outside of our facility was available, we know that he was doing something at the university at least 40-75 minutes per day.

Outcomes and Observations

Across the six-week training intervention we saw consistent pre-post progress across all primary measures. This included a significant reduction in pain, reduced inflammation, and increased functional ranges of motion in early phases of training. Continuing on, this was followed by improvements on all key force plate metrics (Peak Propulsive Force, Braking RFD, and Time to Stabilize). This was the case for each of the three jumps utilized in our protocol (drop landing, CMJ, multi-rebound). As mentioned above, our intervention was provided as an adjunct to what was being done concurrently at his university.

consequently, we cannot say that what we provided was exclusively or entirely the reason for this athlete’s progress. However, we do believe that our impact was demonstrated through the diagnostics and adamantly confirmed by the athlete. The primary subjective takeaway the athlete provided was in the middle of Phase 2, where we started approaching heavier intensities. He said being able “to handle high loads on split squats was the biggest confidence boost” he’d had since his surgery.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

Kylah Broadnax is a dedicated and dynamic professional with a rich background in athletics and fitness. A former collegiate volleyball player at Midwestern State University, Ky’s passion for sports and fitness led her to transition into personal training (beginning in 2019) and coaching club volleyball (2017-2023).

Kylah Broadnax is a dedicated and dynamic professional with a rich background in athletics and fitness. A former collegiate volleyball player at Midwestern State University, Ky’s passion for sports and fitness led her to transition into personal training (beginning in 2019) and coaching club volleyball (2017-2023).

She earned a bachelor’s degree in kinesiology in 2021, which provided a strong foundation for a career in sports training and coaching. Upon graduation, Ky joined Elite Speed & Sports Training (ESST), initially as a head strength coach. Demonstrating exceptional leadership and operational skills, Ky was soon promoted to head of operations, a role she excelled in until 2023.

Currently, Ky brings her expertise to Rude Rock Strength & Conditioning as the Head Coach of their flagship Fascial Fitness program. In addition to this role, Ky recently joined TeamBuildr in the customer support department, leveraging her extensive knowledge to assist and guide users.

Great case study! The structured return-to-play protocol for high ankle sprains in football is very insightful. I appreciate the emphasis on gradual activity increase and monitoring progress. Using tools like kinesiology tape can also provide added support during rehab. Thanks for sharing this valuable guide.