The human performance industry has expanded rapidly, and this growth has precipitated an evolving versatility for S&C coaches and practitioners. Within just the last two decades, we’ve gone from timing gassers and hitting 1RM bench presses to sprinting on 1080s and having mobile, personal force plates.

Things are different.

These differences can primarily be attributed to the effects of technology and social platforms, which have benefited the human performance industry in many ways. To highlight a few: an expansion of work opportunities, increasingly sophisticated performance applications, and direct access to an abundance of resources to improve our knowledge and skillsets. These, among other benefits of today’s human performance model, have provided coaches and practitioners favors in abundance.

The Versatility of Strength and Conditioning

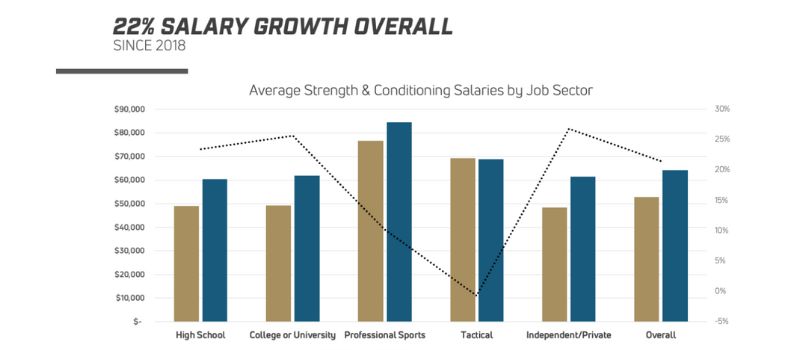

Historically, our work descriptions and applications seemed pretty clear—we help athletes improve physical performance, predominantly through lifting weights and running. And once again, today’s landscape suggests an entirely new reality for us, particularly those in the private sector. For an industry that has objectively been underpaid and overworked since its inception, we shouldn’t be resistant to these opportunities.

(Graphic provided via National Strength and Conditioning Association (NSCA))

This versatility of S&C can materialize in a variety of ways, and for me has been crafted somewhat uniquely over the years. Where the vast majority of S&C coaches fall under either the athlete performance or general population umbrellas, my job has invariably been focused on helping athletes and individuals recover from injury.

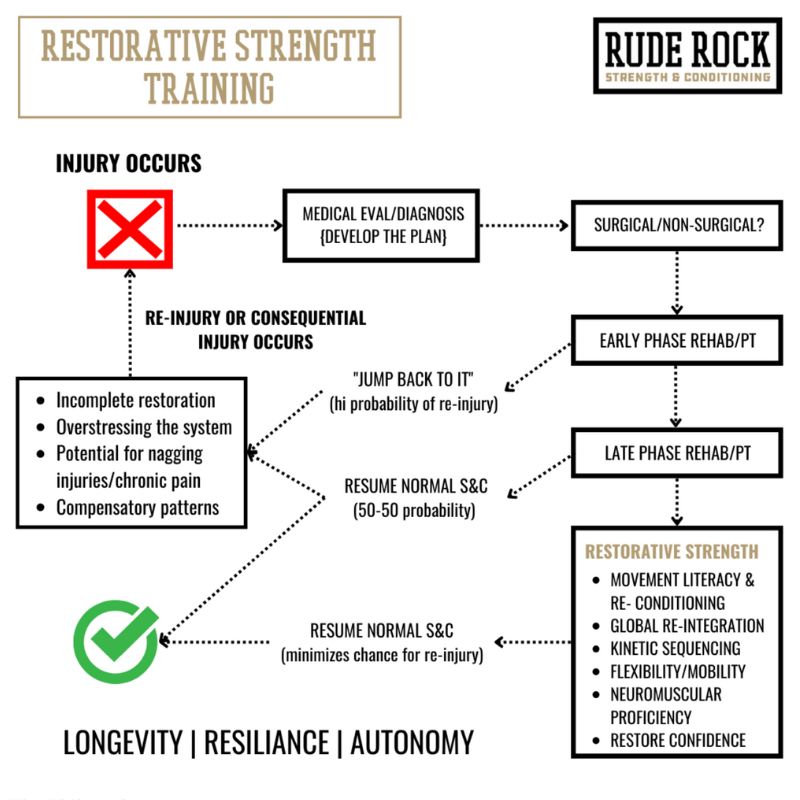

Between my time with Navy SEALs, to now working with professional athletes, I’ve learned that restorative strength training (RST) supported by impacting health and wellness factors is the most effective and sustainable way to recover from injury and manage chronic pain. In this article, I will be covering the philosophy, art, and science of return to play (RTP) for strength and conditioning coaches. These pillars will provide the underpinnings to the structure and applications of this RST approach.

I’ve learned that restorative strength training (RST) supported by impacting health and wellness factors is the most effective and sustainable way to recover from injury and manage chronic pain. Share on X

The Philosophy

The philosophies you hold are the bedrock from which your decisions are formed. Philosophies should be firmly believed but loosely held; in other words, I am always certain of what I am doing, until I’m not. Philosophies should be seen as emergent ideologies that are always open to revision.

The roots of our philosophies should invariably be driven by “how does this help the athlete perform?” The desire to lean towards personal biases or preferences can be strong. Commit yourself to an environment or process that continues to expose you to different ways of doing similar things. This is an effective way to challenge your philosophical views and belief system in an organic way. Our philosophies provide the landscape for our science to be developed; the unwritten rules that we intuitively adhere to:

- Nobody gets hurt on our time. This unequivocal priority speaks for itself, but no pain and no setbacks are always at the front of our focus for each athlete. Every input should be audited based on the potential risk versus the expected return. Make good decisions.

- Health is wealth. Restoring injuries or rectifying chronic pain are invariably dependent on establishing proficient health (physical, mental, emotional) and wellness (sleep, stress, nutrition) practices. Any method, application, or protocol will fall short of fully restoring injuries without a robust health and wellness foundation.

- No treatment in isolation provides a complete solution. The human body is a dynamic matrix of complex systems. These systems provide specific, independent functions that collectively work in tandem to produce unified outcomes. No system works alone, and all systems are interrelated and dependent on another. When athletes sustain injury or have surgery, multiple or all major systems are—to some extent—compromised. It truly takes a tribe and their collaborative effort to provide a complete and effective return to play.

*No pain* and *no setbacks* are always at the front of our focus for each athlete. Every input should be audited based on the potential risk versus the expected return, says @danny_ruderock. Share on X

Video 1. Injury restoration fundamentally requires a multimodal or interdisciplinary approach.

- Every athlete is an n=1 case. Do not create expectations or comparisons for injured athletes. While utilizing normative data and standardized ranges can help guide the path, these should not be viewed blindly as mandatory prescriptions. Beyond the physical uniqueness of injuries, the psychological or emotional response will differ across athletes as well. Relying too heavily on what should be happening can become a significant detractor.

- Progress athletes based on achieving landmarks, not timelines (credit: ALTIS). These landmarks can (and should) vary across populations or times of the year, and depending on the specific circumstances, can be modified to better reflect appropriate goals for the athlete. The landmarks are then progressed accordingly throughout each corresponding phase of the RTP process.

Beyond the physical uniqueness of injuries, the psychological or emotional response will differ across athletes as well, says @danny_ruderock. Share on X

- Humanizing the athlete. RTP is a human-first process. Humanizing the athlete should be a central pillar to any training endeavor; however, as it applies here, injuries typically affect the athlete as much psychologically as they do physically. For this reason, we need to have particular emphasis on restoring that component. As it applies, athlete input is always encouraged, valued, and utilized. They are a part of the working dynamic, not just the subject.

Video 2. Humanizing the athlete is something that invariably applies, whether we are talking about a healthy athlete or an injured one.

- Integrate them into the same environment as the other athletes. Environment and atmosphere are fundamental to producing a positive outcome. Throughout the injury or post-surgical process, athletes are largely detached from their teammates. The last thing that injured athletes want is to be treated or reminded that they are injured. Take them out of the bubble wrap, integrate them with the other athletes, and allow them to work.

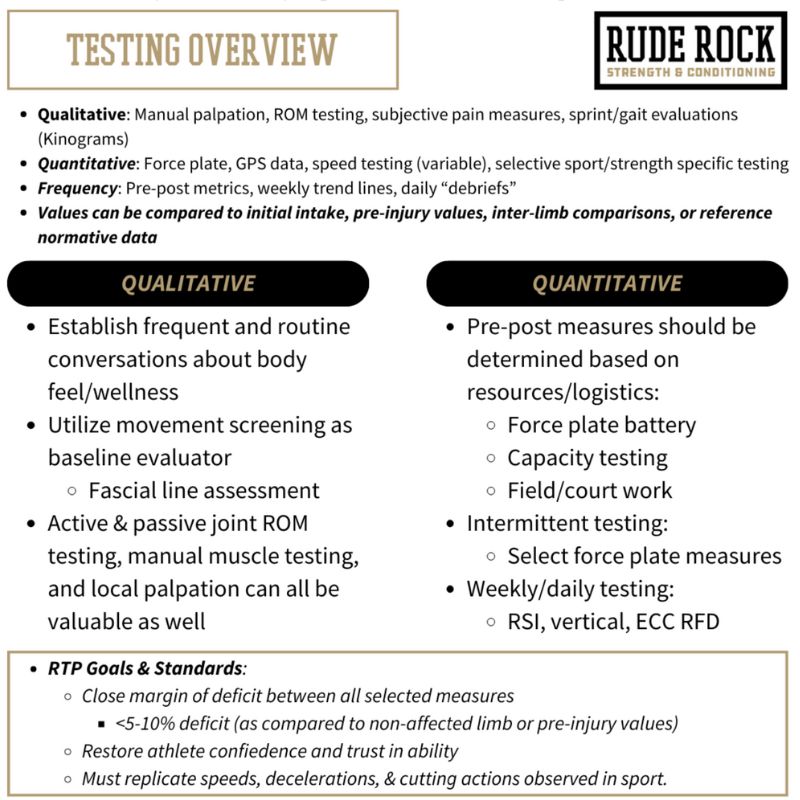

- Measure what matters and keep the goal the goal. This one may seem simple, but with our current crux of information and data overload, it can be easy to get lost in the chaos. My belief is that a blending of subjective and objective measures used in tandem provides a best-practice approach. The subjective evaluation guides the ship, the objective data confirms our route. Ultimately, the end goal is to get the athlete back on the field or court as efficiently and effectively as possible. That will be the empirical evaluation criteria.

The Art

The transaction of coaching is taking an athlete or individual who cannot do something and helping guide them towards being able to do that thing better and with some sense of autonomy. The art of coaching is largely derived from the ability to observe what’s occurring, understanding how that observation relates to the demands of their sport, and being able to make good decisions to bridge the two thereafter. With respect to our n=1 philosophy, we know that the same applications won’t be received the same in two separate occasions. Coaches must be perceptive to individual differences in personality types and learning styles as much as they are to deviations in physiological profiles and movement patterns.

Needless to say, art is intuitive. It is a feeling as much as it is a technical acumen, and only truly develops through firsthand experience. Quality decisions become validated through program adjustments and movement solutions can be justified through data collection. These nuances of coaching develop through a coach’s ability to be keenly aware and make timely decisions with good judgement, coming together in the ability to provide simple solutions to complex problems.

- The “coaches’ eye” may be the panacea for the art of coaching. At the forefront of this is our ability to observe and evaluate movement, which is the predecessor for intervention strategies. Beyond movement, the ability to sense behavioral differences, such as stress-emotional differences, are well within the frame of coach’s eye. Knowing how something should look is important, understanding how it relates and how the athlete receives the input is what becomes critical.

- Think in patterns, not in planes. One of the biggest shortcomings of contemporary S&C is observing and applying movement based on the “three cardinal planes” model. In lieu of this, I suggest seeing movement as being comprised of shapes (isolated positions, joint angles), patterns (how an athlete connects shapes in time and space), and signatures (unique and individual expressions of patterns). (Credit: ALTIS)

Video 3. This model is much more replicable to the movements and the actions that we’re going to be seeing in sport.

- Review and revise. Already a good practice for any coach, this is critical with injury cases to continuously and objectively audit programming. Take notes diligently. The injury process is highly variable and sometimes chaotic. While the end goals and targets may be mostly static, the route to get there is anything but. For this reason, I review daily training notes (training response, athlete input), and then perform weekly audits (total training load, video review, force plate diagnostics).

- Routine and transparent communication. This is vital for any successful training outcome, but should be viewed as non-negotiable for situations involving injury. The priority on communication can be bifurcated as having two primary avenues: coach-athlete and coach-coach/practitioner. Communication should be fluid and consistent, the less ‘obligatory’ dialogue, the better.

- Individualization is required for success when working with injured athletes. The specification for individual demands should be considered equally on the S&C and restorative endeavors. This can be achieved several ways, but a simple and effective strategy can be achieved through manipulating training parameters. Additional factors for individualization include the sequencing, timing, and frequencies of how the program is organized and delivered.

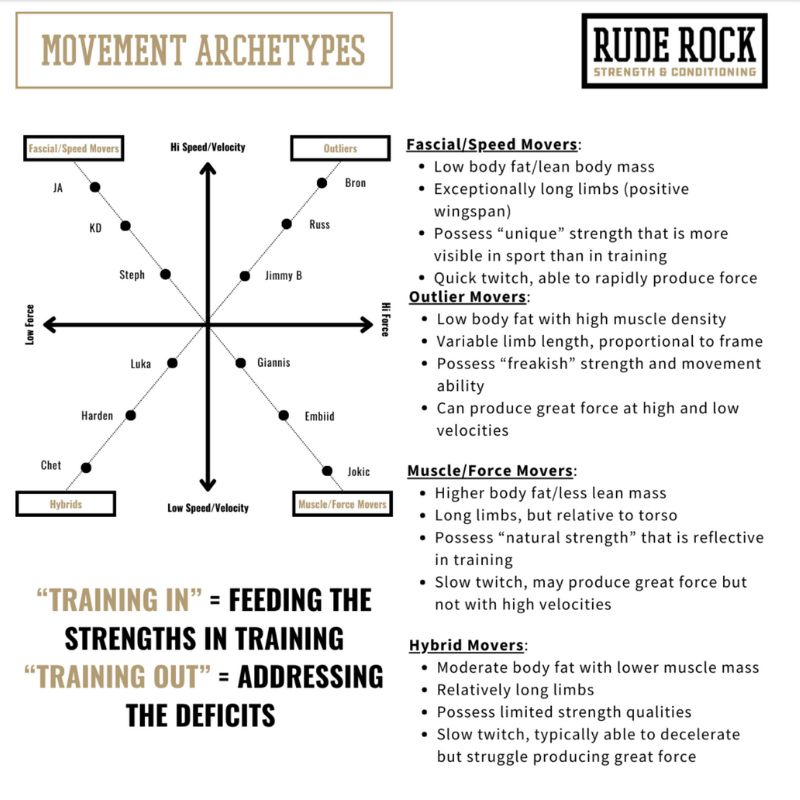

- Classifying athletes by archetype. Athlete movement and physical attributes exist on a broad spectrum, even within the same sport or position group. In line with our goal to be as individualized as we can, a starting strategy is to classify athletes through archetypes (i.e., force or fascial mover). This predominantly helps to determine the ‘big rock’ training parameters (i.e., volume, intensity, velocity, and density).

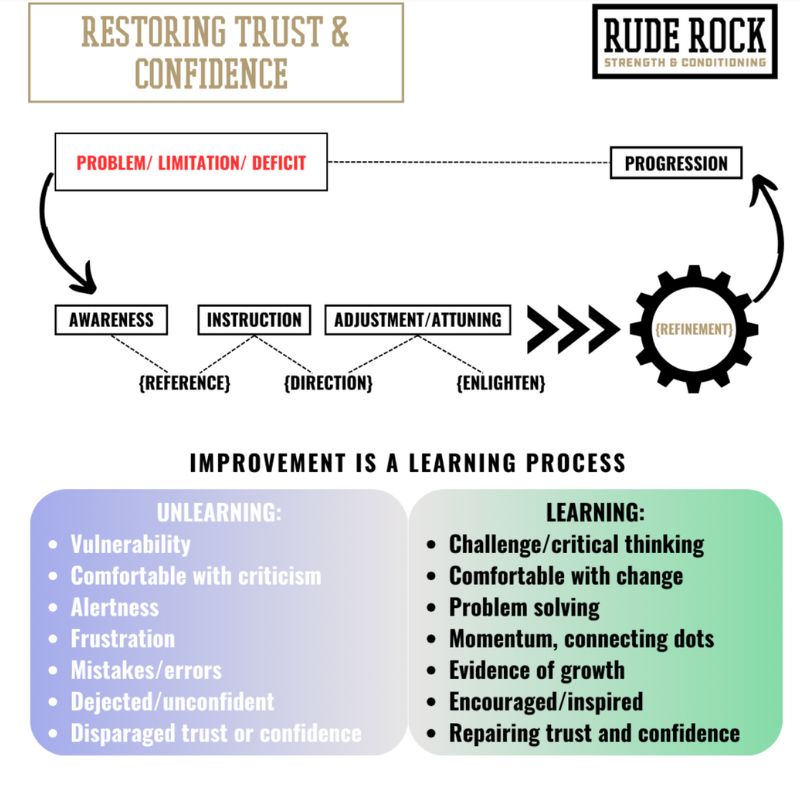

- Movement literacy and athlete autonomy are central to the ethos of restorative training. In order to learn or reacquire movement, the athlete first must be made aware of what’s been compromised or done incorrectly. Once aware, the athlete needs to be educated, or coached, on how they should be performing the task. As the athlete becomes proficient with the skill or task, they can then learn to become autonomous with it.

The Science

The intertwining and/or overlapping of rehabilitative applications and conventional team-based strength training can be a challenging compromise. The overarching goal when working with injured athletes is to keep them as relatively close to “standard” training as possible, without imposing risk. With this, the RST model is intended to abridge and align where the athlete is currently to where they ideally would be or need to be. Where the strength training provides the central adaptations we covet, the soft tissue therapy and supporting modalities collectively work to provide a transient optimal window to apply the stress. The two must be applied in tandem to optimize the RTP process.

The key distinction to RST is that every aspect of programming is designed in an individualized manner that specifically addresses what has been compromised from injury. This is in contrast to having athletes “just get back to training” following significant injuries, which can compromise the thoroughness of restoration. A continuation of care and prolonged individualization plan should be considered as the athlete reintegrates to training. See this as a slow but steady process that is gradient along the way.

The key distinction to RST is that every aspect of programming is designed in an individualized manner that specifically addresses what has been compromised from injury, says @danny_ruderock. Share on X- A diverse biological system requires a multimodal solution. To the best of your ability, within the setting you have, injury restoration must be met with a multifaceted approach. This multimodal structure should look first to address reducing pain levels, improving fluid dynamics, restoring sensorimotor acuity, and improving soft tissue quality. From there, musculotendinous strength, myofascial continuity, aerobic capacity and sport-specific conditioning become the forefront priority.

- Mechanical overload and velocity are what largely drive central adaptations. Both are required for complete injury restoration. A common misconception to RTP is that we need to be overly conservative with loading in fear of causing harm or reinjury. This also speaks to why (conventional) physical therapy has developed a subpar reputation. We need to recall that load is relative, not absolute. And throughout virtually all phases of RTP, we want to relatively load the athletes as much and best as we can.

Video 4. One of the most common misconceptions with injury restoration is that it needs to be “anti-load.”

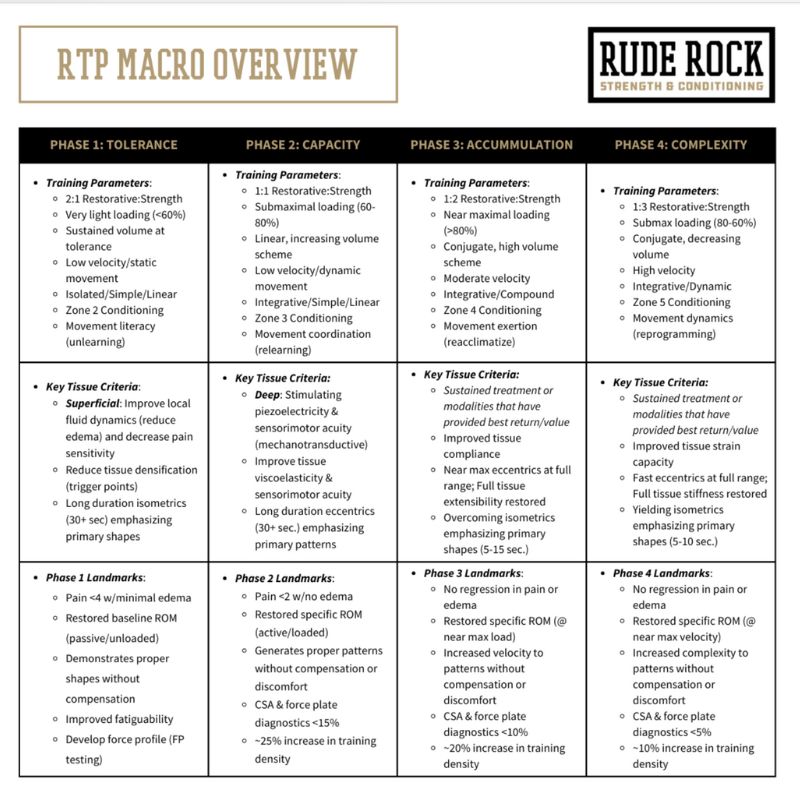

- The macrostructure is developed from a four-phase model. This includes tolerance (phase 1), function (phase 2), capacity (phase 3), and complexity (phase 4). Full details of each phase are shown in the graphic below.

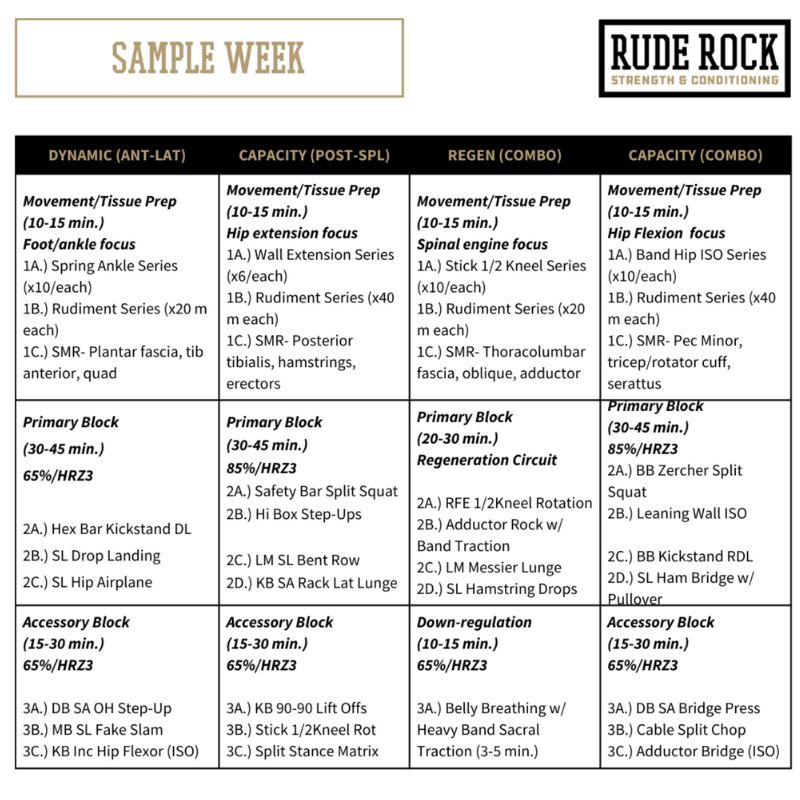

- The daily structure follows a basic block format which are governed by time blocks rather than prescribed sets. There is nothing exceptional to this structure, which follows a conventional movement prep, primary, secondary, and tertiary block schematic. What is a bit different is the time blocks, which are intended to create an autoregulatory application. This allows the volume of training to be determined by the present ability of the athlete, rather than a predetermined number of sets.

- Training is organized by primary fascial lines and grouped as either anterior-lateral or posterior-spiral focus days. The anterior-lateral days are subclassified as flexion-based days, where the posterior-spiral are extension-based. These are then conducted as either capacity, strength, dynamic, regen, or other specific training modes.

- Improving the athlete’s ability to tolerate variability, or expanding movement bandwidth, are also fundamental elements to the RTP model. While progressive overload is fundamental in this training approach, it does not provide a complete solution.

- Balance the contractile capacity and connective tissue resilience. Specified tissue adaptations can be broadly organized as either having a myotendinous emphasis (60-80% | >80%) or the myofascial structures (80-60% | <60%). This coincides with a delineation between emphasizing overload or pursuing variability. A heuristic I utilize here is looking to balance the contractile capacity and connective tissue resilience. Work the spectrum.

- Incorporating fascial-based training concepts provides value throughout all phases of the RTP model. Putting an emphasis on fascia, along with other connective tissues, is essential for complete restoration of injuries. Fascial-based training emphasizes a tight adherence to the principles outlined by the dynamic correspondence model.

Video 5. With fascial-based training, what we essentially mean by this is utilizing that premise of shapes, patterns, and signatures, we are trying to load the body and load the connective tissue specifically in as many ways as we can.

- Dynamic correspondence, originally developed by Yuri Verkhoshansky, states that there are five central criteria to training: amplitude and direction of movement, accentuated regions of force, dynamics of effort, the rate and timing of force production, and the regimen of muscular work. While these principles were designed for the sake of performance, they are equally actionable for RTP athletes as well.

- Programming should frequently utilize time under tension training parameters. This can be achieved a myriad of ways, but generally involves isolating and accentuating phases of movement to provide a progressive stimulus in training. An abundance of research has been published over the years demonstrating the benefits of time under tension for soft tissue structures (tendons, ligaments, fascia).

Closing

Relatively speaking, the human performance industry is still well within its infancy phase. Although we have found a handful of concrete roles and applications of our work, I think it’s fair to suggest we are still probably just at the frontier of where this is all leading.

The expansion of S&C is critical for both the value we can provide to athletes, along with diversifying the financial aptitude of the contemporary strength coach (revenue potential). Strength coaches can not only provide a critical component of the RTP model, but can also provide coaches with specialty skillset that can add tremendous value to their work and income. This can be achieved many ways through many avenues; injury restoration was simply what came to me.

Note: Stay tuned for our new project that will provide with an exclusive insight to RTP case studies, with modules featured on SimpliFaster and running throughout the remainder of 2024.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF