A fundamental role of coaching, irrespective of the specific sport or duties, is to instill confidence in the athletes you work with. In essence, we’re not only responsible for improving physical abilities, developing skills, and educating them on movement, but we also need to recognize the impact of simply helping athletes become more confident with who they are and what they do. Restoring confidence in injured athletes can be just as difficult as restoring the physical injury itself, in some cases. But at the root of this transition is taking what they believe they can’t do and proving to them that they can.

Restoring confidence in injured athletes can be as difficult as restoring the physical injury itself, in some cases, says @danmode_vhp. Share on XI’ve been at Virginia High Performance for about five years now, and for the bulk of this time, I have overseen the training and programming directives. At VHP, we run a concentrated program for active duty and veteran military athletes, most of whom are from the Special Forces and Special Ops groups. Suffice it to say, there’s hardly a dull moment in our facility.

Over the years, we have seen a tremendous spectrum of injuries and adaptive athletes, and the majority of them, despite being injured, still must be able to perform operational duties—and at extremely high levels. There’s virtually no injury that I haven’t worked with by now, and while that has come with a steep learning curve on the physical/mechanical side, it pales in comparison to the psychological battle these injuries have represented. In this article, I’d like to discuss some of these psychological barriers that result from injury, and how we as coaches can be better equipped to navigate training when pain and discomfort won’t seem to dissolve.

The Relativity of Pain

Pain, no matter how you choose to define it, is absolutely a complex psychosomatic occurrence that has a multitude of factors. Pain science is a rabbit hole just about anyone can get lost in quickly. As surprising as this may seem, pain is actually still a relatively unknown phenomenon, especially the origins and relativity components. But one thing is for certain: Pain does not affect individuals equally, and the worst thing we can do is assume in either direction.

Managing an athlete’s pain response to training, at least in my belief, is where the “art” side of coaching really becomes critical. The first step is to establish a pain relativity scale that matches your athlete. Remember, a “6 out of 10” for me may be a “4 out of 10” for you or someone else, so this is again where assuming can be damning.

Once the baseline is established, it’s on you to then configure a way to stress them during training without breaching their individual limits. I’m extremely cognizant of respecting the athlete’s barriers; the main reason being we’re trying to reset their relationship to exercise/training. If we constantly do things that reinforce the pain feedback loop or demonstrate inability, it will indirectly reinforce to them that training makes them feel worse, not better. Beyond empirical and subjective pain scales, I look at three distinct subcategories of pain: anticipatory, associated, and assumed.

Anticipatory: Demonstrated mostly through body language (guarding/tensing) and often subconscious. Detracts from movement by creating dissonance in which concern is prominent thought/focus.

Associated: Demonstrated through optimistic caution (i.e., “Normally when I do this, that happens, but I’ll give it a shot.”); mostly a conscious behavior. Can become an impediment to training if not corrected.

Assumed: Demonstrated through direct, assertive statements (i.e., “If I do this my knee will be inflamed for the next two weeks.”). Compromises training by way of phantom barriers.

Irrespective of the specific pain type, the outcomes are virtually the same—estranged confidence and an impaired ability to focus on task execution. Our goal as coaches or practitioners then becomes trying to identify why they are showing uncertainty and try to assist them in working through the confidence barrier. Simply, if they start with assumed pain, we want to get them to a point where they still may have anticipatory reservations but are at least willing to trust us and themselves to execute. Given enough time and repetition, what was once anticipatory will soon dissolve, but it takes multiple efforts to establish this.

Restoring Confidence in the Injured Athlete

An unequivocal pet peeve of mine is when coaches reiterate or reinforce to someone that they’re injured or that they’ll “never achieve X/Y/Z.” This includes treating them with overzealous fragility and hesitation. It’s important to recognize that the athlete will pick up on your demeanor quicker than you can mask it, and if they sense uncertainty from your instruction, they will adopt it in their action.

It’s important to recognize that the athlete will pick up on your demeanor quicker than you can mask it, and if they sense uncertainty from your instruction, they will adopt it in their action. Share on XAlthough coaches wear several hats during their time on the floor, being the purveyor of what someone can or can’t do is absolutely not one of them. Starting from the point of injury onward, athletes will be met with endless encounters where they’re forced to be reminded of what they can’t do. After so many weeks of recovery, rehabilitation, and general life endeavors, by the time they get to the strength coach, the last thing they want (or need) to hear is how messed up they are.

Now, of course there are additional measures and considerations that the coach must take. Please don’t misconstrue this as ignoring problem areas and throwing athletes right into the fire. I really think that part of this conversation speaks for itself, but you should be very thorough in the “X’s & O’s” of how to accommodate an injury.

What we’re focused on in this context is simply the interaction and austerity you present as a coach to provide them with the perception of trust, knowledge, and confidence both in you and themselves. This is especially paramount with the population we work with at VHP, as most of our athletes are (literally) world-class experts at reading others and detecting emotional shifts through body language. Your language matters, but the way in which you assert yourself and instruct will be highly significant as well. They need to feel the confidence you have in both the situation and their ability to complete the task, not just hear it.

Disparaged Relationship with Training

No differently than how obese/unhealthy individuals have a poor relationship with food, injured athletes can develop a poor relationship with training. It’s not a knowledge or information barrier; nor (in most cases) is it a volition or willingness barrier. The root of the problem is that they have become overwhelmed by injury, and in addition to diminished confidence in their ability, they’re now in a space where movement is perceived as a potential threat. It is absolutely critical that this relationship is amended throughout your time training with them.

In addition to the injured athlete’s diminished confidence in their ability, they’re now in a space where movement is perceived as a potential threat, says @danmode_vhp. Share on X

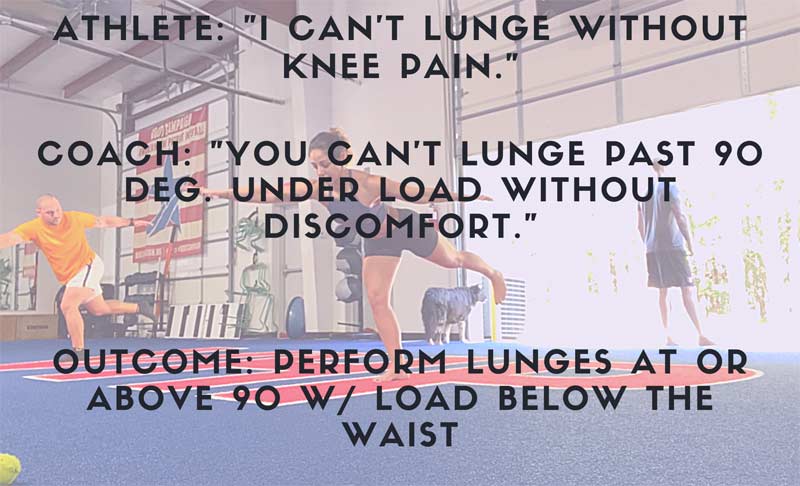

I believe that a fundamental error for a lot of coaches is assuming that the limiting factor is information- or desire-based. Again, at least with a high-performing population, these two are rarely the barrier. I believe what we need to emphasize is restoring their relationship (cognitive-emotional) with training by modifying the perception of what their present abilities are and neglecting the proverbial limits or expectations. It’s vital that the athlete feels like they are in control of their situation and their destination. I see the role of the coach in this instance as that of a translator, whereby our job is to shift what they think or believe into what we can prove to be true.

Shifting perspective can be tough, and this is why I emphasized the “art” component above. But if nothing else, the coach needs to be mindful of general personality type, learning style, and how heavily the athlete values objective or subjective input. If they’re someone who needs more of a nurturing approach, give them frequent positive feedback and reinforce they’re on the right track. If the athlete is more objective or number driven, well then give them just that. Provide tangible evidence of marked improvement—this gives them the positive confirmation bias that what we’re doing is effective.

The better (and more quickly) you can understand the athlete’s personality and history, the more precise and thorough you can be with application and instruction. Ultimately, your efforts must work to recalibrate how they perceive training and their eligibility to do so at a high level. So, as far as positive affirmations, video review, or objective measurables, know the audience and provide them with what they need.

Optimize Movement Signatures

Movement signatures is a concept I was introduced to through the work of Stu McMillan and the ALTIS crew, and it has dramatically improved my coaching. In short, movement signatures are the independent and unique characteristics of an athlete’s movement profile. I believe this has resonated so well for me working with injured athletes because very little falls into what we would conventionally deem “theoretical norms” or standardized ranges.

For instance, if we have an athlete coming off of a SLAP tear, we can exhaust ourselves with textbook data and timeline graphs to assess the improvements for our athlete. However, textbooks often fail to consider items like differences between surgeons and surgery type, condition of the athlete pre-op, mechanism of injury, surrounding joint and tissue integrity, and so forth. Adding to the ambiguity for me are the very unique demands and exposures for tactical operators. But I can assure you, if I compared every one of my SLAP tear athletes to a standardized chart, we would never be in a place where we could perform meaningful work.

If I compared every one of my SLAP tear athletes to a standardized chart, we would never be in a place where we could perform meaningful work, says @danmode_vhp. Share on XIt’s imperative that you apply the relativity factor to injured athletes. Yes, in the first 12 weeks post-op there should be clear markers the athlete should reach, and improvements will be mostly linear. But once that initial phase has come to pass, things just aren’t that black and white. This is where understanding the independent signatures becomes tremendously helpful.

For me, we strictly compare where athletes are now to where they started. Rather than spending an abundance of time on “improving shoulder flexion by 5 degrees” because that’s what a book says, I want to see how I can simply optimize what they have and how they get there. The psychological side to this is a change in paradigm, as they’re no longer chasing arbitrary numbers that may or may not help them at all. Rather, I want them to have an intrinsic focus of “Okay, how can I make this as effective and efficient for me as possible?” The shift in focus alone can be an epiphany moment for the athlete.

Final Thoughts

- Be concise and consistent with your cueing. Injured athletes will already be so consumed by not getting injured again that long-winded cueing and instruction can overwhelm them. Additionally, they will often rely heavily on these cues outside of the facility. Give them tangible pieces they can use in work or practice. Language is one of them.

- Create an effective environment. Have their type of music on, ensure good energy and conversation flow, give them their favorite rack, etc. Make it feel like home.

- Allow them to make (within reason) mistakes. More importantly, allow them to solve the problem for themselves. It’s important that they don’t become externally reliant on you or anyone else.

- Make them sweat! This ties into the whole fragility piece outlined above, but their training has been performed in bubble wrap for weeks if not months… No matter how, make sure they leave every session sweating and feeling like they trained hard!

- Acknowledge how injuries can permeate daily life and how it’s on them to be mindful and manage outside of the facility. This includes things like therapeutic and restorative care.

- Be adept at reading body language and facial expressions and pick up on patterns. A lot of athletes will mask the presence of pain/discomfort very well. They will also be outright indirect with how something feels out of fear of being held back. It’s on you to find the honest answers.

- Autonomy is a major key. Inform your athletes about what’s going on, what you’re applying, and why you believe it’s valuable. Additionally, teach them little things like soft tissue work, breathing drills, etc. that are tangible pieces they can include on their own. I believe the more ownership they have over their training and recovery, the more inclined they’ll be to optimize it.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF