The field of sports performance is relatively young, and because of this, I believe it has plenty of room to grow in multiple areas. One such area is the acknowledgment that each athlete is different from a physical and psychological perspective—recognizing those differences and tailoring your program to them at certain times of the year is often overlooked. An individual’s structure will determine what I consider Superpowers versus Kryptonites.

By structure, I am specifically referring to the infrasternal angle (ISA), the angle made just below your sternum that creates a “wide” or “narrow” rib cage. I find that Narrow individuals typically tend to be more elastic or reliant on their connective tissue for movement than on muscle. Wide individuals are the opposite; they generally have more of a muscular reliance.

Referring to the infrasternal angle, ‘narrow’ individuals typically tend to be more elastic or reliant on their connective tissue for movement than on muscle. ‘Wide’ individuals are the opposite. Share on XIn my opinion, strength coaches as a whole typically only cater to one structure—at least in a majority of their programming. Consequently, the Superpower bucket is typically overflowing for some in the program, while the other type of athlete is dosed with far too much Kryptonite.

There’s a reason you’ve heard countless times that an individual in track, football, etc., ran their fastest and jumped their highest in high school. Then they got to college and trained like a powerlifter and actually got slower and less explosive in the things that are most important. And that importance is not found in back squatting and bench pressing but in running fast and jumping high.

This is not to generalize about the entire field, as there are many high-level practitioners who effectively create programming for both types of athletes; however, I still see certain athletes slowed down by an overemphasis on traditional means. I have encountered plenty of athletes in my career who would rather sprint, jump, and play tag—and who’s to say that’s any less potent of a stimulus than back squats and chin-ups?

Throughout this article, I hope to present the differences among athletes that may lend them to being more drawn to certain training modalities than others and how you can recognize these differences to create a program that benefits every athlete to the highest degree.

Avoiding Kryptonite

Early in my career, I often heard the phrase: “We got the skill position guys in this group; they’re so soft.” What did this mean? To some strength coaches, it meant that these individuals didn’t like to back squat or deadlift heavy—these athletes would roll their eyes and be reluctant to add more and more weight to the bar. The perspective of the strength coach (again, not all, but some) comes from their experience, right? Well, what is their experience?

Most S&C coaches enjoy lifting heavy weights and grinding through reps that produce tremendous amounts of internal rotation and compression. This is because their physical structure is built for this type of training. Because they themselves were born with a structure that complements this task of high-intensity powerlifting, they believe that everybody should enjoy that same thing, and those who don’t are “soft.”

What if, however, that wide receiver who avoids loading up the barbell to near-maximal intensities has a different perspective and structure? A structure that lends itself to being springy and elastic, running fast and jumping high, and spending less time on the ground; a structure that excels in quick displays of external rotation. What if their Kryptonite is actually long-duration moments of internal rotation and compression?

No wonder these athletes want to avoid powerlifting! Doesn’t Superman avoid his Kryptonite as well? Because I’ve mentioned this idea of “structures,” let’s dig into this concept in more detail to see how it relates to the differences among athletes.

Infrasternal Angles

As I mentioned earlier, when referring to “structures,” I mean the infrasternal angle (ISA) found at the base of your sternum, which determines the width of your rib cage. This angle spans a spectrum from narrow to wide. Conor Harris describes individuals with an ISA greater than ~110 degrees as “Wides” and less than ~100 degrees as “Narrows.”

Again, referring back to the introduction of the article, from what I’ve seen, the majority of strength coaches are Wides, and the minority are Narrows. I believe this is why most strength coaches hold the bias toward heavy traditional lifting being the most beneficial—because it is the most beneficial to THEIR structure. They enjoy heavy, deep, bilateral squats and typically don’t enjoy short ground contact plyometrics.

Meanwhile, your typical basketball player usually wants to avoid powerlifting but thrives with plyometrics and lighter, more explosive movements in the weight room. Why does the structure create this bias? A wide ISA has just that: a wider structure. This structure is biased toward internal rotation and compression, as stated previously. The compression within their body occurs from front to back.

Imagine the athletes are lying on their backs and being crushed like a pancake. Notice an individual who pursues powerlifting for a prolonged time, and they will begin to compress anteriorly to posteriorly and widen laterally. This leads to these individuals having more space to move in the frontal plane and also contributes to them preferring a bilateral stance, as they lack “space” to move their limbs forward and behind them (i.e., split stance exercises).

That internal rotation is present throughout the lower body, allowing the femurs to “screw into the ground” and create a large duration of force production. This transfers down to the feet as well, while the rest of the chain is biased toward internal rotation, leading the feet to be more biased toward pronation. Pronation is a position that helps drive force down into the ground for prolonged periods, contributing more to powerlifting-type movements.

Wide ISA athletes are typically more “muscular-driven” movers. To elaborate, these people will rely more on their musculature in a traditional eccentric to concentric nature to produce movement. The benefits? They have the potential to create a lot of force. The downside? They take longer to do it, making it less energy efficient.

Wide ISA athletes are more muscle-driven movers. They have the potential to create a lot of force. The downside? They take longer to do it, making it less energy efficient. Share on XImagine a standstill countermovement jump performed by a very muscular and wide linebacker at the NFL Combine. This test has no rate-dependent metrics; the instruction is “jump as high as you can.” This equates to a deep countermovement jump where the individual can access the big, powerful musculature of their lower body to achieve a record-breaking jump.

Put a time constraint on the jump, however—“You have to get off the ground in x amount of time”—and they will struggle to achieve that same height. Likewise, accessing all that musculature results in a metabolic cost. Contracting musculature is taxing compared to stretching connective tissue. There is no “free energy” found in relying on musculature for movement like there is with tendons. This idea of “free energy” will make more sense when we look at a Narrow ISA’s movement preferences.

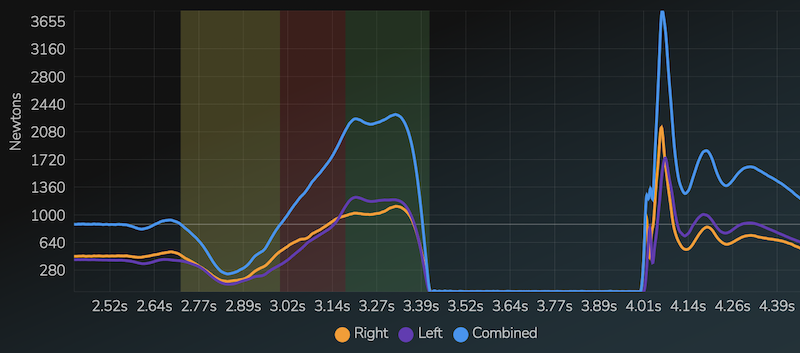

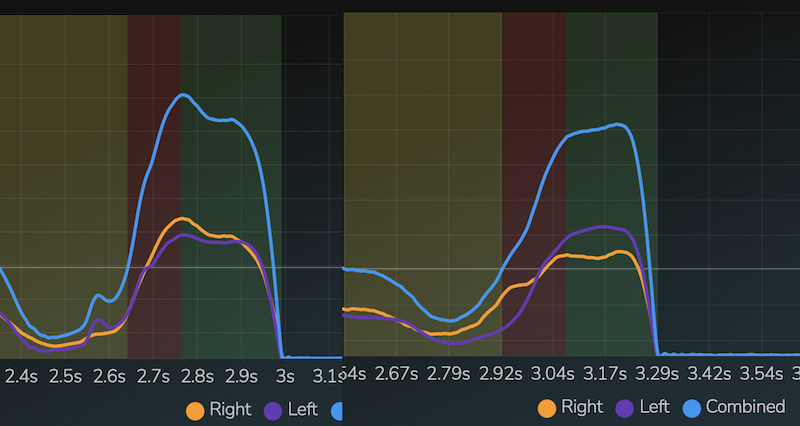

To provide an objective criterion for muscular-driven movers, I begin by utilizing force plates. For a hands-on-hips countermovement jump, a more muscular-driven mover will have a more bimodal force-time curve (figure 1 below), and their rate-dependent metrics (i.e., time to takeoff) will typically be slower. They also will use a deeper countermovement depth.

It is hard to distinguish a muscular-driven athlete from an elastic-driven athlete just by looking at outputs such as jump height, as these metrics may be very similar. However, how they achieve these outputs is much more telling.

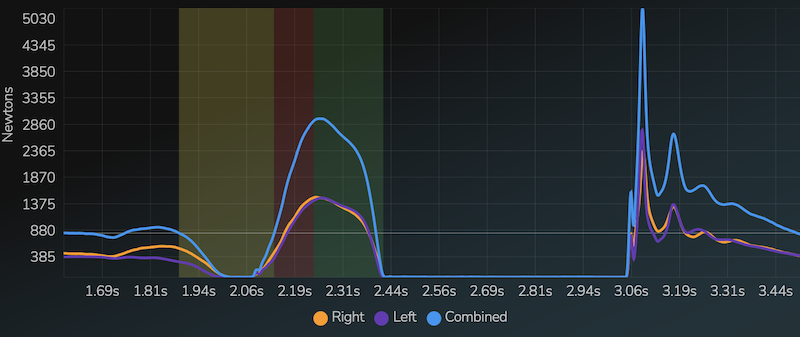

It’s hard to distinguish muscular-driven athletes from elastic-driven athletes just by looking at outputs such as jump height. However, how they achieve these outputs is much more telling. Share on XAnother test I use is a multi-rebound, four-jump test. I believe this assessment shows a strategy preference in terms of an elastic- or muscular-driven mover and also the degree to which somebody is able to rely on their connective tissue to produce movement. The Reactive Strength Index (RSI) may be very similar between a Wide and a Narrow; however, Wides typically spend more time on the ground but achieve a greater jump height to execute their RSI score.

Video 1. A four-jump test is easily performed on force plates or a contact mat. I prefer this test to a drop jump because it shows the repeated and coordinated rhythm of elastic-type jumps instead of one singular jump. Coordination and rhythm are essential qualities to consider when determining the level of someone’s elastic system. I want to measure the efficiency, not just the effectiveness, and the repeated nature of a multi-rebound test, like the four-jump, allows me to do just that.

As you can imagine, a Narrow’s structure contributes to the exact opposite; there is an external rotation bias in the lower body found at the femurs, and their feet will be more biased toward supination. All of these things contribute to this type of athlete preferring less grinding through traditional movements in favor of instead getting off the ground quickly and moving lighter weights fast, typically in a staggered or split stance. The bias toward this stance is opposite to the Wide’s preference for bilateral movements, as Narrows usually have more room anterior to posterior but are more compressed laterally.

A bilateral stance is less ideal, as it moves into that frontal plane where their structure affords them less space; a split stance, by contrast, puts limbs in front and back of the center of mass where they have more space. This split position also avoids high amounts of internal rotation. There are many more biomechanical aspects of infrasternal angles that much smarter individuals than me could explain, but this begins to paint the picture of why taking an athlete’s structure into account when determining the best training prescription is important.

From a movement strategy standpoint, Narrow ISAs are usually more elastically driven. This means they are more reliant on their connective tissue (i.e., tendons) to produce movement than their musculature. This is achieved through the musculature acting isometrically, creating a rigid base from which the tendons can stretch and recoil. The benefits? Much more reactive movement, which is actually more energy efficient.

The body is able to use the “free energy” alluded to earlier. This is because there is no metabolic cost to tendons stretching and recoiling. The downside? This movement strategy is typically limited in the long durations of force application some tasks call for (i.e., American football lineman) but great for sports like basketball, especially at the guard position.

From the same objective standpoint as above, a Narrow and elastically driven athlete may actually have lower jump heights in a CMJ test than their Wide and muscularly driven counterparts because a standstill vertical jump is much more biased toward the Wide’s strengths—especially if we don’t take into account the rate-dependent metrics and only focus on jump height.

The elastic nature of their movement strategy is typically reflected in the form of a unimodal peak in the force-time curve of their CMJ test. From a “how” perspective, a Narrow often had a shorter time to takeoff and a shallower countermovement depth.

Considering all of this, how do you create the best training plan possible? This is where my Kryptonite and Superpower program comes in.

Kryptonite Program

As we dig into this section of the article, you may begin to think, “This contradicts everything said in the first portion,” because I believe it would be incorrect to suggest that Narrow ISA athletes should never train with traditional movements at high intensity in bilateral stances. The key is that it is all about the timing and dosage. It would be ignorant to argue that these traditional movements have no benefit to athletic performance—there are qualities that these traditional movements develop that every individual needs regardless of structure.

Just as a Wide ISA individual will be called upon in their sport to elicit short ground contacts and sprint at max velocity, Narrow individuals will be called upon to produce prolonged and high amounts of force. Just ask Ja Morant when he gets switched onto Zion Williamson and must guard him in the post for a possession!

However, it is important to understand the timing and dosage of Kryptonite you give these athletes. That is really the basis for the Superpower and Kryptonite program: dose the athlete with the right amount at the right time to increase robustness and maximize strengths. Instead, though, strength coaches often dose Narrow and elastically driven individuals with these traditional high-intensity means throughout the entire year, thinking they are “peaking” them with one rep max testing right before the in-season begins.

That is really the basis for the Superpower and Kryptonite program: dose the athlete with the right amount at the right time to increase robustness and maximize strengths. Share on XI typically use the Kryptonite program in earlier portions of the off-season, as there is still a lot of time before competition. This timing is important because training to improve weaknesses may actually decrease your key performance indicators for a short time. This is fine if you know you don’t need your athletes to be at their best for a few months.

I also adjust the dosage of this portion of the program depending on the training age of the individual. A young Narrow may train with traditional means for longer than a Narrow who has trained with me for years. This is because I want to build a large foundation and “raise the floor” with the younger athlete before transitioning to trying to “raise the ceiling.”

I am, however, trying to heighten and “raise the ceiling” of the older individual’s “Superpowers” as much as possible. For example, that younger athlete may train within the Kryptonite program for six weeks of an eight-week off-season, whereas the older individual may only train two weeks out of an eight-week off-season.

So, what does the Kryptonite program entail?

After reading the initial section of this article, I’m sure you can piece it together yourself, but let’s discuss some details. For my Narrow and elastically driven athletes, the Kryptonite program more resembles a traditional training program, and I take time to load them in bilateral stances with increasing intensities. As stated earlier, this may decrease specific KPIs (but in some cases, improve KPIs, especially with younger athletes), and they may be reluctant to dive into this style of training—but after discussing the benefits and the act of improving weaknesses, there is typically much more buy-in.

It’s important to state that these aren’t the only weeks throughout the entire year that you expose these athletes to this traditional style of training; however, this is the highest dosage you should give them. You may dose these methods in small amounts throughout the rest of the year to maintain the “floor” you built during this portion of the annual plan. During this time, you also dive into more traditional powerlifting-type movements, such as deadlifts and bilateral pressing and pulling. Allow your Narrows to develop the foundational strength and hypertrophy that will help them when they aren’t able to rely on their Superpowers.

Throughout this phase, I want to see a couple of things occur with our force plate jumps. First, for the CMJ, I’d like to see jump height go up, but as a product of a greater countermovement depth and even a slightly slower time to takeoff. It is important to remember that jump heights typically decrease during this period because of the intense training; however, the how continues to be important.

You may also begin to see these athletes start to shift their unimodal force-time curve to slightly more bimodal. This is okay! It’s the time of year that we want these things to occur before we begin applying stressors that increase these metrics in an opposite fashion. I’d like to see ground contact time and jump height increase during the four-jump test. The overall RSI may not change, but the strategy is now transitioning to more of a muscular strategy.

Video 2. Remember, the “how” of the CMJ is more important than the absolute outputs. I am less concerned with the jump height than with how that individual achieves that jump height.

The Kryptonite program for Wide ISA and muscular-driven athletes will include the opposite of what the Narrows are doing. I take out all bilateral movements and typically don’t load them with higher intensities. I challenge them to produce as much force as possible in a short time frame, in a shorter range of motion with light loads. I expose these individuals to progressing volume in extensive plyometrics, put them in unilateral positions for both lower and upper body training, and also expose them to movements that involve rotation, such as crawling, rolling, and gymnastic activities.

Objectively, when I go through the Kryptonite phase, I like to see a few things happen that are opposite to what a narrow and elastically driven athlete strives for on the force plates. I am less concerned with jump height scores, and a more rapid decrease in jump height is fine in my view, as long as these athletes are using a shorter time to takeoff and a shallower countermovement depth.

My overall goal with the Kryptonite program is to transition Narrows to behave more like Wides and vice versa. The Superpower program resembles the Kryptonite program, but the groups flip. Share on XDuring the four-jump test, I like to see these individuals begin to transition to a shorter ground contact, even if their jump height doesn’t change. My overall goal with the Kryptonite program is to transition Narrows to behave more like Wides and vice versa. Develop the qualities the other excels in before transitioning to the Superpower program in a few weeks.

Superpower Program

The Superpower program resembles the Kryptonite program, but the groups flip. The Narrow and elastically driven athletes now train the way the Wides and muscularly driven athletes did in the Kryptonite phase, and vice versa. While this may be slightly redundant, this looks like:

Narrows and Elastically Driven Superpower Program

- Avoid high-intensity, bilaterally loaded exercises that will force excessive and prolonged exposures to internal rotation.

- Avoid loading in a way that will create increased levels of compression (bilateral, both upper and lower body).

- Rely on staggered and split stances for lower-body movements.

- Focus on the speed of movement rather than the intensity of movement.

- Allow movements to include rotation and freedom, especially with upper-body training.

- Include variation to plyometric training with more elastic-based movements (i.e., fewer “stand still” vertical jumps and more single-leg approach jumps).

Video 3. My time at UC Davis with Men’s Basketball was the first time I unveiled this Superpower program, and it has been under constant refinement since. I considered these athletes to be elastically driven OR so far on the muscularly driven spectrum that I wanted to expose them to more elastic training. It’s important to note that I still include elements of muscular-driven movements, but the overwhelming majority of the program is elastic training.

For objective measurements on the force plates:

CMJ

- Jump height goes up.

- Time to takeoff goes down.

- Countermovement depth becomes shallower.

- Sharp unimodal peak.

Four-Jump

- RSI improves primarily through decreased ground contact time.

- RSI improves secondarily through increased jump height.

Wides and Muscular-Driven Superpower Program

- Allow these athletes to get back under some higher intensity load in bilateral stances and grips from a lower and upper body training perspective.

- Allow for more time to generate force with our faster movements and load them slightly heavier than the Narrow and Elastic Superpower program.

- “Peak” by hitting high-intensity movements (1–3 rep max) close to the season. I believe this not only creates physiological benefits but also psychological benefits, so they “feel” their strongest heading into a season.

Video 4. These individuals were either muscular-driven or young athletes who needed exposure to more traditional training to lay a proper foundation.

For objective measurements on the force plates:

CMJ

- Jump height goes up.

- Time to takeoff goes down.

- Countermovement depth becomes deeper.

- Ideally, by this point in the year, these individuals have developed enough of the elastic qualities required and heightened their Superpowers so that they are able to achieve a faster time to takeoff with increased countermovement depth. This involves them moving through the loading phase of the CMJ faster and slamming on the brakes rapidly.

- Bimodal peak that transitions from secondary to primary or primary to unimodal.

Four-Jump

- RSI improves primarily through increased jump height while ground contact time holds steady or slightly improves.

It is important to note for this phase of training that we will be getting closer to the preseason period when coaches are given more time for the actual sport, and it is essential to prepare the athletes to withstand that increase in volume as well as try to maximize Superpowers. For example, while Wides may not thrive with excessive amounts of plyometrics, increasing volume in that area is essential to build resiliency in both archetypes for what sports typically entail.

Speed development is also progressed concurrently with this program, and I typically look to touch my highest outputs (velocity) and develop a robust repeat sprint ability through protocols like 10 x 10 (made popular by Derek Hansen), regardless of what program the individual falls within. The next development within the Superpowers program is to begin individualizing the speed development portion of training, tailored to archetypes, strengths and weaknesses, movement strategy preference, and training age.

Incorporating the Concepts with Your Athletes

As I stated in the introduction, alluding to experiences from my past, I don’t believe those strength coaches were trying to be ignorant by saying that certain athletes they were training were inherently “soft” because they didn’t like squatting heavy. It just takes an introspective approach to realize that not every person has the same frame of reference as you.

I’ve heard from multiple individuals within this program, specifically the Elastic Superpower group, that they feel so much better going into a season. They feel light and springy, not stripped of what makes them special by grinding them through heavy bilateral movements.

The idea of ‘peaking’ an athlete by having them ‘PR’ their squat and bench before the season is a completely outdated way of thinking. Share on XThe idea of “peaking” an athlete by having them “PR” their squat and bench before the season is a completely outdated way of thinking. Continue to do this, and these elastically driven athletes will step onto the court for game one, missing their most powerful weapons. This might sound dramatic, and I agree that athletes are highly resilient; however, the goal is to optimize training for every individual.

Everybody is different. Everybody falls somewhere on the Narrow to Wide and elastic-to-muscular-driven spectrum, and it’s important—and, dare I say, imperative—to take that into consideration to create the best possible program for our athletes and get the absolute most out of them. Give structures, Superpowers, and Kryptonites a chance.

As always, with anything I write, please feel free to reach out with feedback, either bad or good, and/or any questions you have! Let’s continue to try moving the needle.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF