On October 10, 2018, Hurricane Michael struck Florida, causing $25 BILLION in damages. Florida is no stranger to typhoon-like conditions, being the U.S. state with the most hurricanes (currently sitting at 125 since 1851). With residents knowing what to expect, you’d assume they’d be highly prepared for the conditions of their home state…but you’d be surprised to learn that many don’t retrofit their homes for hurricanes. Most Floridians just build their houses to regular United States code—a decision that could lead to roofs being blown off, walls being knocked down, and entire buildings being lifted from their foundation.

If you’re like me, your first thought is that it’s just too expensive to hurricane-proof every house—but we’d both be wrong. Building a “hurricane-proof” house from scratch only increases the price by 5% compared to traditional architecture. In fact, hurricane-proofing a roof on an existing house costs as little as $1,000, on average. Even so, many residents still choose the more familiar and traditional blueprint plans. In a similar manner, some coaches still view conditioning and footwork with the same antiquated and unprepared mindset.

The gap between ‘fit’ and ‘game shape’ is a never-ending dogfight for strength & CONDITIONING coaches everywhere, says @endunamoo_sc. Share on XAny athlete who has ever graced a court or a field knows there are different forms of “in shape.” Coaches countrywide during fall camp can be heard claiming, “We need to get in game shape.” Running stairs, gassers, and suicides might help you pass a fitness test, but it won’t get your team ready to play four quarters, two halves, or nine innings like the game itself. The gap between fit and game shape is a never-ending dogfight for strength & CONDITIONING coaches everywhere.

So, how do we address the hurricane of game readiness that all athletes face? By playing games, of course.

A Three-Step Approach to Game Readiness

When I work with team programs, I am almost always approached by a sport coach who has their own idea of how training should look. Smiling faces are forbidden, and puke buckets are highly preferred. They want the kids to suffer in the rain as if it makes them more prepared for the heavy winds to come. Somewhere along the line, we confused “mental toughness” with “in shape,” and the time to course correct is NOW.

I own a 12,000-square-foot athlete-specific training facility that works with athletes of all ages and levels and from a range of communities. Although we are known more for our ability to increase vertical jumps and drop 40s, we put a lot of effort into ensuring our athletes are fit enough to handle the demands of their sport (and whatever conditioning test the head coach is excited to do that year). Our athletes range from 7-year-olds who can’t run in a straight line to professional bull riders and everything in between. Even with a wide range of individuals, they all have one thing in common—the love of competitive games.

Games provide a unique training stimulus that monotonous line running cannot. In his book How We Learn to Move, Rob Gray talks about how skill mastery can be achieved—not just from perfect repetition, but rather constraints-based learning. Constraints are boundaries that athletes have to recognize in their environment and then self-organize around to complete a task. The idea that all great reps are perfectly the same can be destroyed when you watch multiple slow-motion videos of professional athletes swinging bats, clubs, and punches.

Although the end result is the same, the path to achieving success varies depending on the situation. A great way to teach athletes about self-organization is to put them in an unfamiliar environment with a unique goal and movement rules that force them to create a positive outcome. You might be surprised to see them create their own unique solution to a movement problem—a great example is watching Patrick Mahomes make plays that most QBs couldn’t even bend or twist to try.

The problem with most traditional conditioning is that athletes can premeditate their pace, breathing, and footwork. Running dozens of repeated sprints or shuttles allows the mind to create efficiencies in movement and energy expenditure. However, a competitive game forces three-dimensional thinking and decision-making, and therefore, inefficient moves, accelerations, and breathing patterns. Likewise, competitive games provide an environment to practice patterns and enter spaces, safely increasing their movement toolbelt.

How can we expect athletes to master their environment when we only allow them to experiment when the game is on the line? You can’t hurricane-proof a house after the rain has started to fall. Share on XHow can we expect athletes to master their environment when we only allow them to experiment when the game is on the line? You can’t hurricane-proof a house after the rain has started to fall. Without a safe space in which to make mistakes and play with positions and moves at high speeds, most athletes revert to “comfortable” footwork patterns and movement strategies—definitely not how the Patrick Mahomes types would approach the situation.

Watch a group of athletes play a non-familiar sport and pay attention to how many of them hold their breath to help make a move or stop. Notice as they try to problem-solve an unfamiliar situation and have to hustle extra hard to make up for their mistakes. Take notes when you see them make a move that might even surprise them. A great example of this is watching football players try to play basketball or soccer. They’re athletic enough to play at a high speed and tempo but uncoordinated enough to introduce self-constraints and freezes to make plays.

Now, I’m not saying that we should throw out generalized conditioning; however, we should incorporate more energy- and movement-specific work throughout a training cycle to minimize the fit-to-game-shape gap most athletes suffer from. This does not mean that all footwork games are appropriate for all sports, but we can modify them to match space and energy system demands.

Before we dive into one of the toughest footwork-fitness games our program deploys, I want to talk about our three-step approach to developing game-ready footwork and skills in athletes of all ages.

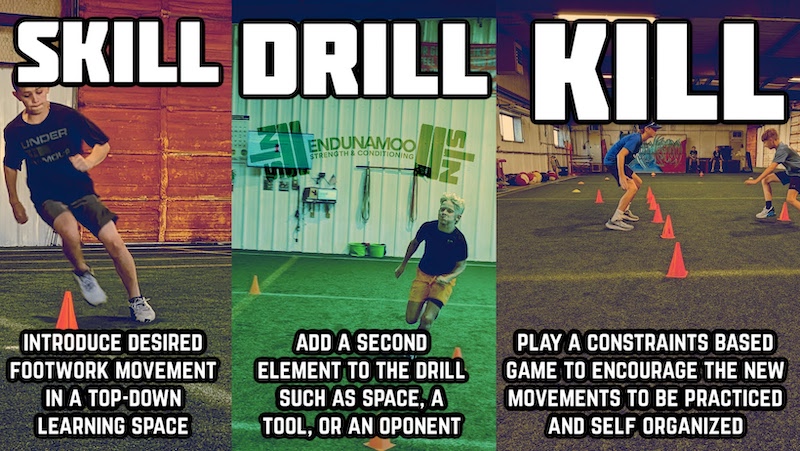

Step 1: Skill

This is a traditional coaching strategy also known as top-down teaching. Top-down teaching starts with the big picture and then works down to the specific details. For footwork, this would typically be teaching an ideal movement or pattern we want an athlete to use in a particular situation. We then do a few slow, controlled reps to familiarize each athlete with that skill.

Step 2: Drill

At this point, we’ve been working on a movement for a few minutes and want to add space to challenge the adherence of the new abilities. This part typically involves more cones, distance, and a secondary element like a tennis ball, an opponent, or responding to a stimulus. Once athletes succeed in this phase and do the movements correctly, they begin to gain confidence in their new weapon. This is extremely important in seeing these patterns being used in higher levels of competition.

Step 3: Kill

This is where we introduce a constrained, game-like situation that favors the athlete who can perform the practiced skills and drills. That being said, all moves are welcome as they explore winning strategies and push their fitness levels to the max. Depending on the game, we might play Last Man Standing rules, where athletes who win get to stay while losers are slowly eliminated. This allows less-fit, less-skilled athletes to be challenged at their current levels, while the more advanced can push themselves and be challenged as well.

When it comes to skill development, each athlete has a window of good reps. You can create a negative and discouraging environment by performing too many “bad” reps with novices. This is a significant strategy we use since our facility has many different levels of athletes.

Game On

Now it’s time to talk about one of the most mentally challenging, speed-building, energy-demanding games that I have ever used or played: Curved Infinity Tag.

Most coaches understand that running in sports involves more than just straight lines, and therefore, our footwork and speed training should contain curves and swerves as well. Our annual calendar uses a progression of curves for all our athletes, starting at a half circle and eventually finishing with figure eights for field athletes. Not all sports share the exact same energy and space demands, so we modify how far we take a drill’s progression and how much space it is allowed to cover to have a higher sports carryover.

Energy Demands

This particular drill does a great job of conditioning our athlete’s fast oxidative-glycolytic fibers and the immediate energy system—the primary motor for most power sport athletes. A great rep in this drill CAN’T last more than 15 seconds. The intensity will slowly fade as fatigue kicks in, forcing one athlete to go for the kill or the other to give in to the exhaustion. By performing several reps of this game with multiple opponents, you’ll eventually begin to find that it not only builds change of direction and problem-solving but also sport-specific fitness. In basketball terms, this is the triple-triple of footwork drills. To further bait athletes to compete, we reward the last person standing with a title or a prize of the day.

The Curved Infinity Tag drill does a great job at conditioning our athlete’s fast oxidative-glycolytic fibers and the immediate energy system—the primary motor for most power sport athletes. Share on XEach time we do a version of this drill, we start in this format.

1. Skill

We always start at slower paces and smaller spaces to get rid of the bad reps. Athletes are instructed to sprint down and back on HALF the size of that day’s space. For example, if we’re doing a full circle, our athletes will do a semi-circle sprint down and back (about 2–4 reps per direction). This allows them to self-organize their footwork and movement for that day while providing the coach with time to correct any abhorrent cuts or moves.

2. Drill

For our second phase, we will open up to the entire space and add a tennis ball or a relay race. Each athlete must sprint the circle, pick up the ball, and bring it back to their teammate, who then sprints to return it home, competing against a clock or another team (another 2–4 reps). This could be where you stop for the day; however, to incorporate conditioning and a space for decision-making and problem-solving, we move on to Infinity Tag.

3. Kill

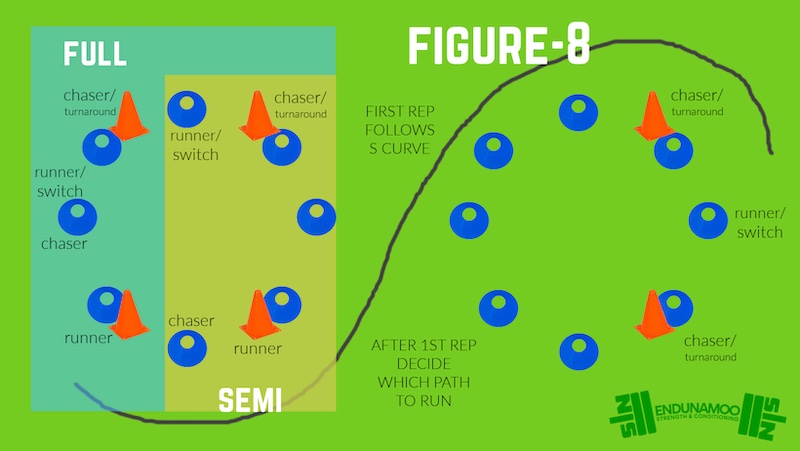

Finally, we take our circles and instruct the athletes to simultaneously tag and/or evade their opponent. The drill starts with a Runner and a Chaser. On the whistle, the Runner tries to escape to their CHASE cone while the Chaser attempts to make a tag. If unsuccessful in the provided space, they have to touch their TURNAROUND cone. No one is allowed to change direction until they reach their specific cone.

Once the roles are reversed, both athletes run in the opposite direction until both reach their other cones OR a tag is made. And it happens again. And again. And again. What starts as an all-out sprint turns into a game of strategy as they run out of gas and oxygen. The winner is usually whoever can give an all-out burst and make the tag on their tired and unprepared teammate. When we play this game, we give each athlete 2–3 lives and let them battle it out until only one really, really, really tired person remains.

Elevate the Drill

As I mentioned before, we normally start practicing this drill with a semi-circle formation and then expand the arena space if appropriate. Since all sports involve some small space footwork, EVERYONE can benefit from the first phase.

Video 1. Curve sprint Infinity Tag.

The second level is a complete circle, which doubles the space and problem-solving. The rules are still the same, with a constant back and forth, using a 5-yard diameter circle—which works a space that all sports will benefit from.

Video 2. Full circle Infinity Tag.

The highest level we use is a figure 8 formation, covering a space of up to 15 yards—this is usually reserved for our field athletes. Since court sports typically have limited space, we don’t always work to this level, but almost all of our field athletes will. This is my favorite version of the drill because it involves a third level of game play—directional decision-making.

Athletes are required to start by running a figure S to their alternate cones. However, once the Runner becomes the new Chaser, they can decide to continue their figure 8 loop or cut directions. Likewise, at the intersection, they can decide to continue the figure 8 or simply run the outsides of the loop to the next cones.

The reps go on and on as the patterns change and become more or less complex. Sometimes, the drill ends in a glorious diving tag, while other times, the chaser can beat the runner back to the middle, forcing a tag. In a fast 15 seconds, athletes can cover over 70 yards and a handful of cuts, curves, and hip flips. The intensity is so high on these that even your most conditioned competitors will run low on gas after five reps.

The intensity is so high on these drills that after five reps, even your most conditioned competitors will run low on gas, says @endunamoo_sc. Share on XVideo 3. Figure 8 Infinity Tag.

This type of footwork training is designed to mimic some of the intensity and energy demands of a game and should be one of the last things you do in a training session. In many cases, the athletes are tapped and unable to produce valuable effort anywhere else in training. As I mentioned in the beginning, this will look like footwork training from the outside, but it will feel like conditioning to the athletes.

Our annual calendar works alongside our speed, strength, and power planning, which allows us to revisit these exact drills months later. Although we may not do this drill every week, I have been able to see athletes’ engines and self-organization increase. The kid who only lasted three games last time slowly makes it five, six, or even seven reps.

When we pair up some of our more competitive athletes, we see their reps get longer and longer. What used to take 10 seconds now takes 15, and then 20, and so on. If we ever have a group that seems to dominate the game, we will begin giving everyone more “lives,” which results in more total volume. There are so many ways to increase the value of these drills that you just have to apply them to your kids and go from there.

So, when we know that our athletes will face metabolic and speed storms, rather than build them using the generic blueprints our grandfathers had, we should reinforce them in a way that not only prepares them to weather the storm but to come through the other side victorious.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF