Starting with the end, ultimately, we want our athletes to be able to execute “sport specific activities with the greatest possible intensity, frequency and sustainability”—aka, become fitter (Mladen Jovanović). Being unfit will therefore inevitably limit our maximum possible output and precision throughout the game and give us fewer possibilities to succeed. If we want to outrun a game, or at least be fit enough to create sufficient scoring opportunities, we need to think about how to best invest our time and energy into any sort of conditioning method to improve or at least not suck at this crucial physical capacity.

There seems to be an emotional controversy about the preferred method to implement in order to elicit superior gains in ‘fitness,’ says @DanielKadlec. Share on XAlthough we have a plethora of conditioning methods available in our toolbox, there seems to be an emotional controversy about the preferred method to implement in order to elicit superior gains in “fitness.” (I’m deliberately avoiding any reductionistic metric.) While we can choose from tempos, continuous steady-state cardio, cross-training, Tabata, Fartlek, MAS, RST, HIIT, SIT, SSG, ACDC, and more, their common claims of distinct adaptive responses seem to disappear when adjusting for total heartbeats per session1. Understanding that those methods have more overlying similarities than discrete differences can stop us from overthinking and wasting planning time and help us accept that many paths lead to Rome—aka being “game fit.”

Threshold This, Lactate That… Does It Matter?

And the list goes on, with big words like mitochondrial density, left ventricular hypertrophy, H+ buffer capacity, PCR re-synthesis, anaerobic speed reserve—and this is just a snippet of what I was taught and what I perceived to be critical to understand if I wanted to plan an effective conditioning program. This, in combination with the fallacious belief that every such “lab-discovered” limiting capacity can be improved with only one method, made me waste hours and hours trying to piece it all together while keeping my approach periodized and sport-specific. The more I went down the reductionistic rabbit hole, the greater my confusion. Today, I couldn’t care less about what any of this even means.

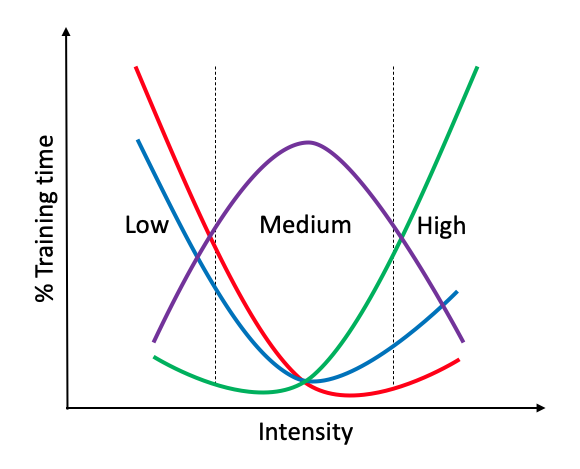

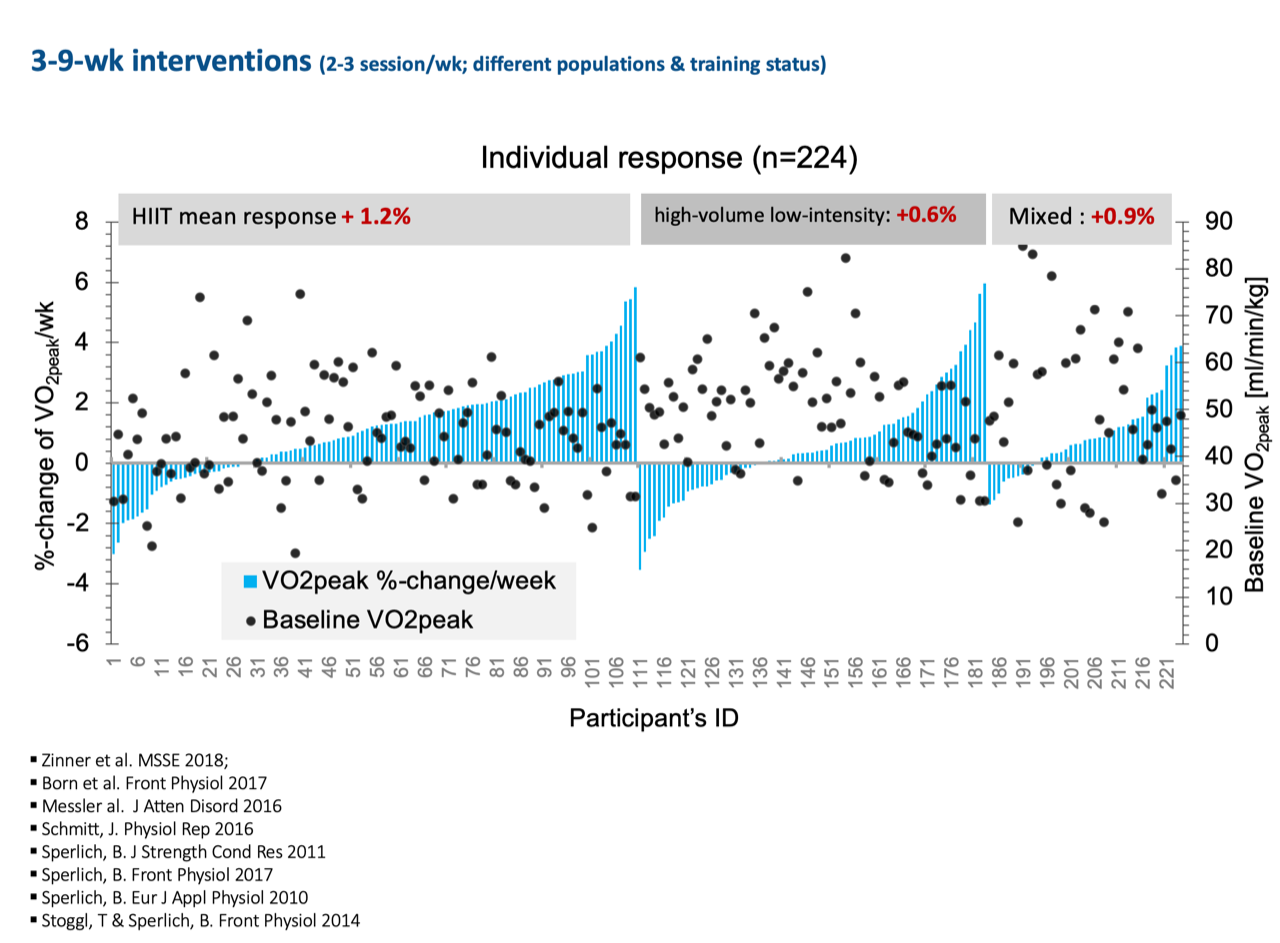

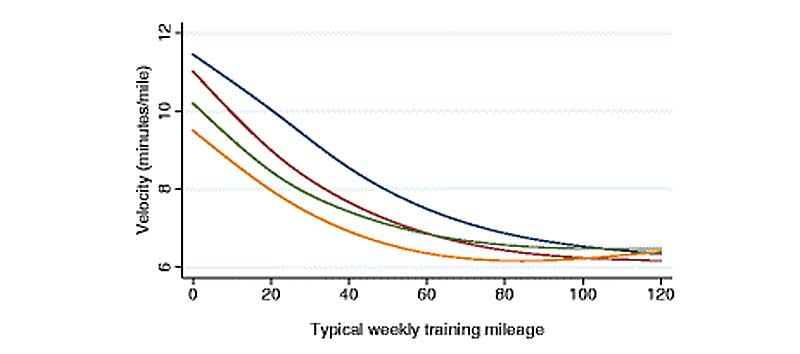

With the end goal in mind—being game fit—the main challenge is to identify the most appropriate and efficient combination of intensity, volume, and modality that fits our respective context. While we know both ends of the continuum (high volume versus high intensity), and anything in between (figure 1), can elicit tremendous fitness gains and have led athletes to remarkable running performances, we also need to acknowledge—as with every intervention with this complex and nonlinear system called human—the inevitability of individual responses (figure 2).

While the relative risk of non-responding is equally high in each approach in trained athletes, it would be nothing but foolish and narrow-minded to selectively invest our resources in just one approach, especially with team-sport athletes. Furthermore, it seems that fitness gains are more robust and less fluctuating in less fit athletes following a high-volume approach compared to other methods2. Although, we accept and promote a “vertical integration” approach with everything we do in the gym throughout the whole season, it seems many are married to an “either/or” approach with their conditioning preferences.

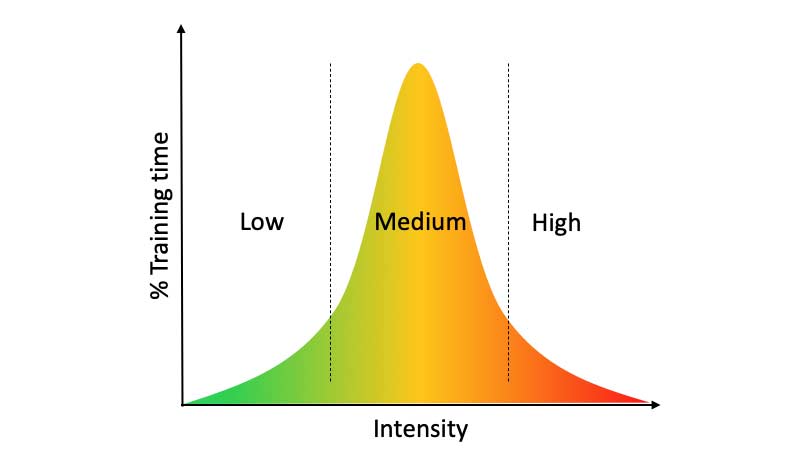

To further polarize the discussion as to what approach to use, many methods have not only distinct, but flawed, evidence-based adaptive certainties attached to them in order to calm our order- and structure-seeking minds (i.e., if you do conditioning type X, then adaptation Y will happen) (figure 3), but also fundamentally arbitrary dogmas. Despite popular belief, every energy system is, congruently to every strength quality, 100% trainable. Its necessity, however, depends entirely on the strengths and weaknesses of your athlete in combination with the specific demands of your sport.

Also, where is this dogma coming from that high levels of blood lactate are destroying your mitochondria?! (Now reading this, it feels like the pinnacle of reductionist thinking, while fundamentally ignoring complex systems.) If true, every single wrestling, judo, and ice hockey athlete in the history of mankind would have literally zero functioning mitochondria. It’s laughable, and reality proves it wrong.

Know Your Game

We all know it’s easy to make someone fitter, but the million-dollar question is, are we preparing the athlete for the demands of the game as well? Especially for the physiologically and mechanically most stressful demands, which coincide to reflect the most crucial, game-deciding moments. While there is now an endless number of metrics I can use to inform my decision-making, I’m limiting myself to high-speed running volume (anything above 5 m/s or 18 km/h in my context) and time @ >90% heart rate max.

This is because, first of all, if you can’t tolerate running fast repeatedly, you will have fewer chances to put yourself into scoring opportunities, while your hamstrings are a ticking time bomb. Second, the team/individual who makes the first mistake during highly contested and intense game plays due to an inability to maintain appropriate skill execution or decision-making typically gets scored against, while only insufficiently recovering for subsequent bouts. Having deciphered those metrics as my primary conditioning KPIs, I can now start to reverse-engineer and determine what my athlete doesn’t experience during practice yet will definitely encounter during a game.

I’m preferentially choosing those methods that can give me either a ‘high-speed running’ overload or a ‘time >90% HR max’ overload, whichever suits my current context, says @DanielKadlec. Share on XAs training time is always precious, and the SAID principle still governs all adaptive responses, especially when looking from a phenomenological point of view, I’m preferentially choosing those methods that can give me either a “high-speed running” overload or a “time @ >90% HR max” overload, whichever suits my current context—i.e., tempo runs or any intensive interval setting with a work:rest ratio of 2-3:1, which ensures heart rate stays elevated. As a rule of thumb (thanks to Martin Buchheit), if you want to stay fit, you need >5 min @ >90% HR max per week and if you want to get fitter >10 min @ >90% HR max per week is a good start. Done.

Apologies to all exercise physiologists who still believe highly specific interval types are necessary to elicit any superior adaptations, while in reality total time @ > 90% HR is a “good enough” stimulus and the main driver for getting fitter independent of interval type3. In my understanding, both types are located within the high-intensity approach and can be further adjusted to meet secondary KPIs such as acceleration and deceleration efforts and specific work:rest ratios; again, if practice doesn’t tick these boxes already (video 1).

With that, it’s obviously highly beneficial to know what the specific demands of your respective game and practice are so as not to rely entirely on a best-guess approach. Using evidence, technology, and/or interns equipped with stopwatches are all great ways to get more insight into what your athletes are dealing with. That’s my first box to check—I push the ceiling with high intensity.

Video 1: Adjusting the conditioning modality to additionally expose the athlete to acceleration and deceleration efforts. Sorry for the video quality, but you get the idea.

Since I don’t know what the game and practice demands are, as mentioned before, I put all my resources into what the athlete is not experiencing but needs. The athlete already gets bucket loads of the medium-intensity part, so I therefore fearfully avoid tapping into it. I just can’t see any additional benefits, since the stimulus is already fundamentally oversaturated (figure 4). However, there seems to be an exponential interest in the potential benefits of SSGs (small-sided games)—aka doing more of what you are already doing—over the last decade based on publication numbers, with its assumption to get fitter while improving your technical-tactical abilities at the same time. Yet, “the man who chases two rabbits, catches neither.” (Confucius)

Doesn’t EVERY drill already include at least two players doing some sort of sport-specific tasks for a certain period of time followed by a rest? Yet now we call it “SSGs,” even though it has actually been around for as long as sports exist. The good thing is we now have about 438 papers highlighting the statistical significance between 6v6 on a 30m x 30m and 5v5 on a 25m x 25m pitch on any “lab-discovered” metric. Every time a new method promises superior gains per unit of invested resource, you should be highly cautious and skeptical. Simply put, “there is no substitute for hard work.” (Thomas Edison)

Polarized FTW

Now that we effectively overloaded the high-intensity needs and successfully neglected the medium part, we need to accept and acknowledge the undeniable potential of the high-volume/low-intensity approach, which fits perfectly into a polarized model. However, everyone seems to hate it… why?

Is it because of this reductionist fear of a muscle fiber shift? I’d agree, if you never EVER sprint, accelerate, jump, and/or lift. Is it because it can add fatigue? I’d agree, if you never heard of the concept of progression. Or is it because it’s not fun? Try sucking at your sport—that’s not fun either.

For decades, if not centuries, steady-state running was the basis of all physical preparation programs independent of sport or occupation, while still being able to show incredible feats of lightning-fast movements—think of all martial arts forms or every single team sport up until the late 2000s. And, if I remember history right, didn’t Rocky Balboa single-handedly end the Cold War by defeating Ivan Drago (after a full 15 rounds!) with nothing but continuous steady-state cardio in the snow?!

Since we know that fitness is, in plain terms, primarily a function of a sheer accumulation of additional heartbeats per unit of time—think “more equals fitter”—it’s no surprise that fitter athletes are those who just have a higher total weekly running volume (figure 5). With their heart rate increasing linearly during submaximal intensities, there is just no substitute to exposing athletes to high(er) volumes if you want to reap the benefits from this approach.

While this method is obviously more time-consuming, it’s just not suitable as a top-up method after practice compared to a high-intensity approach. So, we can either tell our athletes to go for a longer jog on non-practice days—or any other conditioning method that we deem most appropriate for this athlete—or chop it into bits and invest 10–20 minutes before AND after every practice. Remember that weekly volume, independent of its accumulation, drives fitness, especially with less-fit athletes being less prone to not responding. In order to keep it truly low-intensity, I usually instruct them to “hardly break a sweat,” and after completion I want them to feel like the run can’t possibly have made them any better. That’s the second box I tick—I pull the floor with high volume.

Never Not Running

As with everything in life, consistency is the essence of any progression. If you’re not doing any conditioning work on a weekly basis for up to 50 weeks/year (enjoy your winter vacation), it’s less important to debate about the method of conditioning. A consistent approach also just can’t be outperformed by any “HIIT block” or “shock micro cycle” as, although the fitness gains are impressive, the reversibility after not being exposed to this stimulus density anymore is almost perfectly equal to the rate of adaptation. Short-lasting gains for a lot of pain, or as Bruce Lee said 50 years ago, “long-term consistency trumps short-term intensity.” Additionally, in the absence of any acute or chronic injury, the law of specificity dictates not to expect any meaningful benefits to your running performance when doing biking/rowing/boxing/AirBiking if your fitness level is not shocking.

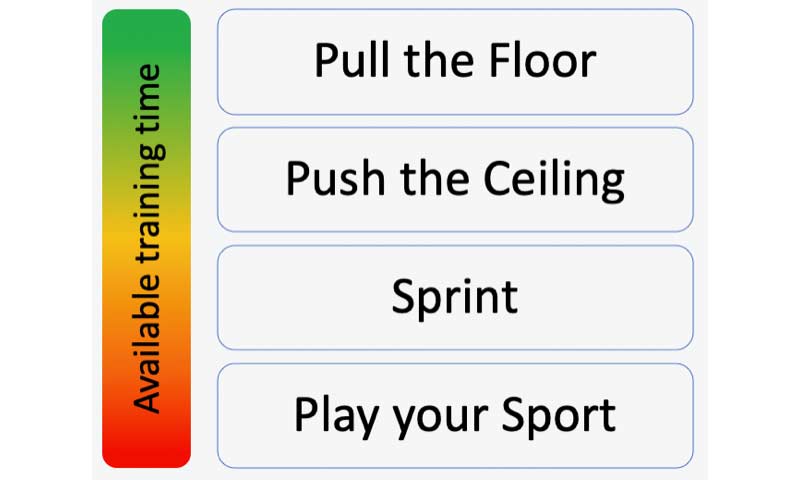

If you want to become fitter for your sport, the hierarchical order for how to best invest your time is: pull the floor, push the ceiling, sprint, play your sport, says @DanielKadlec. Share on XTicking those easy-to-implement boxes has profoundly simplified my approach to conditioning for team sports. I’m spending little to no time deciphering the meaning of all the “lab-discovered” breakthroughs and have stopped worrying I might miss out on any new or magical 1%-er. Anyone remember mouth taping?

Here is my recommendation, in hierarchical order, for how to best invest your time if you want to become fitter for your sport (figure 6).

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

1. Rodrigues JAL, Philbois SV, de Paula Facioli T, Gastaldi AC, de Souza HCD. “Should Heartbeats/Training Session Be Considered When Comparing the Cardiovascular Benefits of High-Intensity Interval Aerobic and Moderate-Intensity Continuous Training? A Critical Appraisal.” Sports Medicine Open. 2020;6(1):29. Published 2020 Jul 15. doi:10.1186/s40798-020-00257-8

2. Zinner C, Schäfer Olstad D, Sperlich B. “Mesocycles with Different Training Intensity Distribution in Recreational Runners.” Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 2018;50(8):1641-1648. doi:10.1249/MSS.0000000000001599

3. Fitzpatrick JF, Hicks KM, Hayes PR. “Dose-Response Relationship Between Training Load and Changes in Aerobic Fitness in Professional Youth Soccer Players” [published online ahead of print, 2018 Nov 19]. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance. 2018;1-6. doi:10.1123/ijspp.2017-0843

4. Vickers AJ, Vertosick EA. “An empirical study of race times in recreational endurance runners.” BMC Sports Science, Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2016;8(1):26. Published 2016 Aug 26. doi:10.1186/s13102-016-0052-y