I am often brought into the fold to work with high-performance athletes on improving their running mechanics, whether it is with track & field competitors, professional teams, or elite college athletic programs. Sometimes this takes the form of providing instruction to the coaching or performance staff on the intricacies of sprint form as it relates to their respective sports. Even more often, I find myself teaching private sector strength and conditioning professionals how to work with their athletes—of all ages and abilities—on developing improved mechanics for faster, more powerful running performance.

Integrating Sprint Mechanics into the Fitness Routines of Your General Population Clients

In the private sector cases, facility constraints often limit performance coaches, given that square footage can be very expensive to maintain for a performance training operation. In many cases, private facilities rarely have more than 20 to 25 meters from wall to wall in which to run their sprint sessions. The open area sections reserved for speed and agility work often have a surface of artificial turf or a rubberized floor. However, when linear distance is limited, coaches cannot expect athletes to practically or safely approach their maximum speed capabilities. Thus, I work closely with coaches to devise a strategy for improving acceleration and overall sprint mechanics within the space provided.

Very recently, I spent an intensive two-week period with coaches and trainers at a facility in Lower Manhattan, New York—Drive 495—owned and operated by high-profile fitness trainer and professional, Don Saladino. Drive 495 is a first-class facility in the heart of the SoHo neighborhood in downtown New York City. Don’s at the helm and other exceptional trainers and physical therapists are there, including Charlie Weingroff, Chris Wicus, and Cody Benz. The combination of experienced professionals at the top of their game and a well-outfitted facility make Drive 495 a very attractive destination for big-name actors, fashion models, CEOs, golfers, and athletes. But even the Drive facility has some limitations when it comes to introducing sprinting as a means of training clients.

At the far end of the facility, an open space surfaced with artificial turf provides approximately 18 meters of linear space that is 8 meters wide. The area of the entire gym itself offers almost 50 meters of linear distance, but much of that space is used to provide access to gym equipment, changing rooms, and a therapy room. There is a narrow lane where clients can perform relatively low-velocity sled pushes on a smooth linoleum floor. When the gym is less busy, athletes can do some sprinting along this same strip of floor, exercising caution to avoid collisions with other gym members.

Things got very interesting when I collaborated with Don and Chris to instruct Drive 495 staff on sprint drills and acceleration technique as a professional development in-service. Don also introduced me to a curved-profile, self-powered treadmill known as a TrueForm Runner. Thus, given the space and equipment at my disposal, I was up for the challenge of providing the best possible training model that the staff could integrate with their general population clients. I think the result is a pretty good substitute for an outdoor sprinting workout.

Starting with the Basics: Dealing with Gravity

Regardless of the space at my disposal, I always start beginners with a very basic technical model upon which to build greater complexity, higher intensities, and the changing posture experienced during acceleration and maximum velocity sprinting. I have had exceptional success using the drills developed by Gerard Mach to teach running mechanics, but also building the necessary strength in beginners and injured athletes engaging in return-to-play activities. As people work through marching, skipping, and running drills under appropriate guidance, they develop the musculature and elasticity to provide horizontal propulsion and, more importantly, vertical force production.

It is important to point out that, through my travels, I have found that coaching these drills properly has become a bit of a lost art. I was fortunate to have grown up during the glory days of Gerard Mach’s infusion of coaching mentorship in Canada, being taught the Mach drills at the age of 11 onward. My time spent with Charlie Francis further refined the technique. Coaches that can impart the finer points of the Mach drills to athletes have a distinct advantage over those that do not possess this skill.

The ‘A March’

I love the Mach drills because they provide a very simple means of teaching limb mechanics in a controlled fashion. The marching drills allow you to literally “walk” athletes through the posture and limb movements required for sprinting. The “A March” involves a rehearsal of the vertical qualities of stepping from stride to stride and coordinating arm movements to match the front-side characteristics of the legs. Athletes can maintain maximum hip height by lifting the knee of the swing leg to a point no higher than the height of the hip. As the foot descends downward vertically, it is placed very slightly ahead of the support leg by a few inches. This is the athlete’s first lesson in avoiding over-striding at the expense of hip height.

With general population clients, use of the “A March” is akin to the movements of a Tai Chi martial artist or a classical dancer, both of whom recruit muscles in a manner that advances their movement skill, mobility, and strength. I also use the “A March” to reinforce the pattern of vertical limb travel. While so many athletes are irresponsibly taught to push horizontally on the ground, the “A March” teaches clients to bring the knee to an optimal height and then accelerate the foot downward to a point slightly in front of their center of mass.

There is no need to move quickly during this drill. Clients can progress at a speed that they feel most comfortable with during initial training sessions. At slow speeds, with clients staying on the balls of their feet with slight elevation of the heel off the ground, the “A March” can provide quite challenging work. Muscles are recruited to hold posture while the limbs may move through ranges of motion not typically experienced by your fitness clients.

The ‘A Skip’

While the “A March” introduces postural concepts and limb movement mechanics, the “A Skip” adds limb velocity and elastic response to the exercise. I ask clients to maintain the same posture and limb paths as the marching version, but now accelerate the foot downward to the ground, invoking the stretch reflexes in the foot and lower leg on ground contact. As a result, the client should experience some degree of positive vertical displacement—a concept integral to good sprinting.

You want your clients to vault upward as a result of their downward force on each stride. The intent is to provide light and quick foot contacts, not stomping foot falls. As with the “A March,” the intent of the skipping version is to specifically strengthen the muscles required for sprinting. It is a fantastic means of bridging the gap between the “A March” and the more demanding “A Run.”

The ‘A Run’

The “A Run” provides a more tangible cyclical simulation of actual sprinting. The stride frequency requirements are closer to the four to five strides per second experienced in high-speed sprinting. A good progression when working with fitness clients is to limit knee height during this drill to maintain optimal posture and establish a desirable stride frequency.

Some athletes respond better to a designation of “step-over” height relative to the stance leg. You can designate a lower height “A Run” as ankle step-over height, with calf step-overs qualifying as medium height and opposite knee step-overs designated as maximum height. As the client achieves key milestones (e.g., posture, limb frequency, foot elasticity) at a given “step-over” height, you can advance them to the next level of intensity.

The “A Run” prepares clients for numerous aspects of true sprinting, including stride frequency and vertical force production, but also closely matches the metabolic requirements of sprinting. On average, I try to have athletes produce no less than 30 strides over a 10-meter distance. I tell them that an elite sprinter running 30 strides maximally can take them approximately 65 meters. Performing two sets of 4 x 10m of high speed “A Runs” with easy walks back between reps can be exceptionally demanding, taxing the musculature of the upper body, core, and lower body. They can also do marching, skipping, and running A drills with a resistance band around the hips to reinforce a leading hip position, as demonstrated in Image 2.

Moving Faster: Starts and Accelerations

While the drills can be a good way to introduce sprint mechanics and muscular conditioning, the real thrill comes with accelerating and getting the feel of actual sprinting. When working in a confined space, it is not necessary to run much further than 10 meters for beginners. Teaching the clients how to implement starting technique can cover several sessions alone.

When working in a confined space, it is not necessary to run much further than 10m for beginners, says @DerekMHansen. Share on XOne of the first positions I have beginners do is to start from an extended push-up or plank. I allow them to step forward with one foot, as demonstrated in Image 3, and then have them run off the ground. Fitness clients can do the same, accelerating for a few steps in the initial training session. Once an individual shows proficiency in this start position, I have them start right out of the bottom of a push-up. Sprinting from a prone position off the ground allows clients to attain a reasonable drive angle for their accelerations.

Teaching your clients to implement a relaxed falling start from a semi-crouch position is the next stage in your start training. Encouraging them to rotate forward over the front foot before exploding into the acceleration phase is an energy-efficient means of implementing numerous accelerations. As with all starts, the action begins with a strong lead-arm movement, as demonstrated in Image 4.

A more advanced start technique that helps to build overall starting strength and power is the medicine ball falling start, as demonstrated in Image 5. Similar to the regular falling start, the client rotates over the front foot and then powerfully throws the medicine ball as far as they can, using both feet before initiating the first stride in the acceleration phase.

Maximum Velocity Mechanics: Getting Front Side

While it would be great if you could take all your clients to an outdoor track facility, this is not always possible. In the case of the Drive 495 experiment, we kept our training subjects inside and used a curved-profile manual treadmill to work on maximum velocity mechanics. The problem with conventional treadmills is that they do all the work for you. Put your foot on the front of the treadmill, and the motorized belt sucks your foot backwards—all you have to do is pick it back up and recover it back to the front side of your body again.

Curved-profile manual treadmills are a good option in lieu of an outdoor track facility, says @DerekMHansen. #CurvedTreadmills Share on XThe curved-profile manual treadmills require much greater contribution from the athlete to get the belt moving backwards. As such, the downward vertical force requirements—creating both vertical displacement and horizontal propulsion—are more significant than those required on a conventional motorized treadmill. The Woodway brand of these types of treadmills is very popular, but Don Saladino introduced me to a TrueForm Runner at the Drive 495 facility. The difference was that the Woodway incorporated flywheel technology that helps to keep the belt moving as the athlete creates momentum. The TrueForm Runner treadmill does not have a flywheel, so it requires more contribution from the athlete or client to maintain speed.

Having never run on a TrueForm Runner treadmill, it took me a few sessions of experimentation to find my “sweet spot.” With a few workouts under my belt, I was able to find a groove with my front-side mechanics and attain reasonable maximum velocity mechanics for brief durations. Because the treadmill was not driven by a motor or even a flywheel, I found that I could only maintain high-speed sprinting mechanics for about four to five seconds before my technique suffered. Given this fact, I had to establish optimal work to recovery ratios for my training sessions.

If I wanted to sprint at high speeds, with significant front-side mechanics as demonstrated in Image 7, I could only do four to five second sprints with about 120 seconds of walking in-between bursts. Additionally, I could only put together four to five repetitions before I had to take much longer set breaks. Tempo running at much lower speeds could be done with a more balanced front-side to back-side stride mechanic.

I would perform 30 seconds of running with 30 seconds of walking for four to five repetitions for a total of four to six sets. The TrueForm Runner doesn’t let you relax on the treadmill. Instead, it forces you to maintain relatively sound mechanics at various speeds, and I was noticeably more fatigued than if I did the same workout on a conventional treadmill.

It is worth noting that we tried sprinting on several other treadmills, including the Technogym SkillMill and the Woodway Curve. SpeedFit, Greenjog, XForm, and Assault Fitness also offer curved-profile manual treadmills. It is not yet clear to me which brand of curved, manual treadmill offers the most versatility, but I am encouraged to find an option that can offer the best platform for sprinting, tempo running, and general endurance training, in lieu of a reasonable outdoor training option.

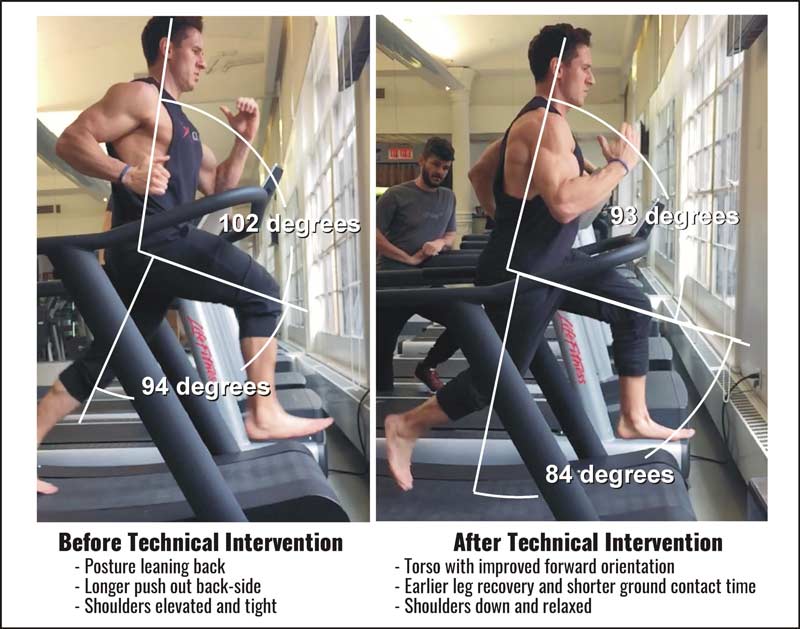

Teaching clients how to run at higher velocities with more-efficient running mechanics needn’t be a difficult task. Use of the Mach drills in a preparatory session, followed by good coaching while on the curved-profile manual treadmill, can be a very effective approach to enhancing the performance of any runner. With the use of simple video technology, you can provide clients with real-time interactive feedback on their running form. It is easy to undertake the biomechanical analysis of stride mechanics and body posture, as illustrated in Image 9, with “before” and “after” screenshots providing clear evidence of positive change.

Leaning for the Finish Line: Making It Work for Your Clients

While we always look for “optimal” training scenarios for our athletes and clients, they are rarely possible. Using sprint drills, short accelerations, and high-speed running on a manual treadmill can prove to be a pretty good alternative to an actual track workout. During the winter months when inclement weather is prevalent, these indoor strategies can help to bridge the gap. Here are some great points that you can pass on to your clients to get them “on board” with a modified sprint-based training program for your facility.

Calorie Burning and Body Composition

There are no fat sprinters out there. Just look at the animal kingdom or watch the Olympics. There is no running for recreation—just running for your life. Survival of the fittest takes precedence. Thus, getting your clients to engage in sprint training can be a very efficient means of improving body composition and general health. The sprint drills themselves can be exceptionally demanding, especially when done properly. Just as stomping on the gas pedal in your car can burn a lot of fuel, sprinting can get your clients to burn calories at a higher rate.

Incorporate elements of the drills into the latter portion of a client’s warm-up. I have always found that doing sprint drills and sprinting prior to weightlifting improved the efficacy of my strength training. The same could be said for your clients.

Recreational Runners and Running Economy

Running at higher velocities requires the body to make use of the elastic properties of all connective tissues. When competitive athletes or recreational runners train these elastic properties, these qualities can make them more efficient runners at slower speeds over longer distances. The top marathoners in the world have exceptional elastic qualities that allow them to run each of the 26 miles in a marathon at a pace of 4 minutes and 40 seconds. In order to achieve such a pace, I anticipate that they are also capable of running under 11 seconds in a 100m race.

For the average recreational runner, working on higher speed qualities through sprint drills and actual sprinting can transfer to their 5km, 10km, marathon, or triathlon performance. Research has also proven this through the use of simple plyometric exercises for long distance running athletes.

General Tissue Health

The “use it or lose it” phenomenon applies in this case. Individuals who do not progressively challenge their muscles and tendons are destined to lose the strength and elasticity that these tissues are inherently meant to demonstrate on a daily basis. While many people can get injuries from over-use conditions, I believe that many others get injured from under-using specific tissues. Just as bone density can suffer from lack of stress and force absorption, tendons and other structures can wither from lack of use. Introducing sprint drills in a progressive manner can be useful in maintaining the quality of these tissues. Even if your clients do not engage in full-out sprinting, the drills can be a good means of maintaining overall tissue health and performance.

Mental Health Benefits

Nothing feels better than moving fast with ease. As we age, we are often discouraged from doing anything deemed too intense or extreme. Sprinting is a test of your suitability to survive and thrive in this life. Given that sprinting is one of the most intense activities that you can perform, being able to sprint on a regular basis appears to be a very good assessment of both your physical health and your mental proficiency, given the extreme neuromuscular demands of such an activity. In a time when chronic stressors dominate the landscape, having periodic exposure to high-intensity acute stressors such as sprinting can have a balancing effect for individuals.

I would like to thank Don Saladino, Chris Wicus, and Thiago Passos of Drive 495 for working closely with me on developing a sustainable model for sprint training with the fitness population. Their insights into making this approach accessible to their clients was invaluable in bridging the gap between elite performers and the general population. I look forward to collaborating more in the future with this group of professionals. Please stay tuned for more high-quality resources on how to implement a sprint-based training program with your fitness clients.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

Outstanding article!