I want to begin this article with a pretty clear disclaimer: I am not the foremost expert on Dr. Michael Yessis’ “1×20 system.” In fact, I was once a giant skeptic of the program. How could this be a thing that people took seriously? One set of 20 reps? I pictured our football players doing hang cleans with 15-pound dumbbells. It didn’t make much sense to me, and it certainly had very little transfer to sport.

Despite my best efforts to ignore the talk and promotion of this program, I could never seem to escape it. Eventually my professional curiosity led me to stumble upon an opportunity to hear about this 1×20 thing when North Scott (Iowa) High School’s strength and conditioning coach, Tony Stewart, presented at the 2018 NHSSCA National Conference on the subject. I figured I was there, why not hear what he had to say?

I ended up realizing that the 1x20 program weaponized our layering system by adding a depth and width to it that I had never imagined possible, says @YorkStrength17. Share on XAgain, in the interest of full disclosure, I didn’t pay as close attention as I should have. It did, however, spark a small interest—enough of an interest that I began to do some digging. The further I dug into this dynamic program of athletic development, the more I knew this program was far from being just a few sets of 20 reps. In fact, I ended up realizing that the 1×20 program weaponized our layering system by adding a depth and a width to it that I had never imagined possible. Some love it, others hate it. One thing is for sure though: If you can’t at least see value in its potential, you definitely need to dig a little deeper.

[adsanity align=’aligncenter’ id=9082]

Peeling Back the Onion

Most programs have some sort of developmental-based layering system within them, and ours is no different. I have written several articles outlining our particular version, with the primary theme being to slow-cook the athlete. I am a proponent of making our system of progression as detailed as possible in order to ensure our athletes get the most out of each level of adaptation before moving on to the next level.

When I am programming, my base goal is to squeeze out every drop of training adaptation possible and then move forward. Moving slower will extend the developmental process and leave somewhere to go as the athlete gains more experience and training age. If I see an item selling for $1,000, does it make much sense to walk up and hand the person selling it $2,000? Obviously, it doesn’t because that’s significantly more than is required to attain the desired item.

Why give away that extra money when I didn’t need to in order to get what I wanted? Maybe I can even get the item for less if I tried? Either way, we know that the asking price is the maximum needed resource to spend to achieve success. So instead of depleting my resources at a level above what I require to achieve my goal, why not use the bare minimum and have the unspent resources available to use at a later time?

Along the same lines, why would I jump an athlete to a higher intensity level or more advanced protocol when they still experience the desired adaptations at lower intensity and more basic protocols? Now, you absolutely can achieve the acute desired result, and $2,000 would most definitely get me the item desired. That decision lacks foresight at every level possible. In fact, some may call it, at the least, inefficient and maybe even foolish.

Jumping athletes with lower training ages (particularly those whose main focus is outside of either competitive powerlifting or Olympic weightlifting) into higher intensity loads or more advanced protocols falls into the exact same category. Doing so will (most likely) achieve the acute goals we desire. But it will also deplete resources that you could have used later in the athlete’s training life to extend the desired strength adaptations.

Simply stated, if you hop over lower-intensity programming in the early years of an athlete’s training before those intensities stop producing strength adaptations, you are allowing your ego to take away from the chronic development of the athlete. I’d rather squeeze every ounce of strength possible from each step of intensity before moving on. This means a longer period in lower intensity and less-advanced modes but leaving the athlete with room to grow later in their development process.

It’s most definitely a sticky situation for some. Coaches often hang their hat on the fact they can produce incredible strength gains in younger athletes. Sport coaches, parents, and administrators that have less of a background in evidence-based athletic development—or no background in it at all—often judge us based on absolute strength numbers. There is little doubt that this is a fact.

The reality is that making a human stronger is by far the easiest aspect in athletic development. Yes, the athlete must put in the effort. However, the process of progressive overload is not a complicated one. I’ve said before that you could send a child into the woods for a month with a group of athletes. Give the child instructions to have the athletes pick up a big rock and carry it as far as possible, then every day grab a heavier rock and repeat.

The athletes will come out the woods stronger. It’s not really a chest-pounding event to make a 15-year-old stronger. The question is, rather, what road do you take to help that 15-year-old become the most powerful, strong, and fast 18- or 21-year old that they can be?

Being willing and growth-minded enough to step back and see the big picture…that’s the chest-pounding moment. I believe that when I began to embrace that philosophy, it made me better at providing our athletes with what they needed, as opposed to what I thought they should have. It’s also what made me begin to take a serious look at what this crazy 20-rep program was all about.

Move Toward 1×20

All layering or “block” systems are built on progressions, whether in movement, volume intensity, proficiency, etc. Every coach who utilizes a layered program can attest that it helps produce the results we desire with greater efficiency and safety. What led me to finally take a deep dive into 1×20 was a statement on a podcast I happened to listen to a while back, where Yosef Johnson was discussing the system and his mentorship under Dr. Yessis.

The trigger moment for me was when Yosef described the Dr. Yessis program by saying (something along the lines of): “The difference between Doc’s programming and most others is he has a depth of progression and movements that is second to none. It’s almost obsessive.” That statement stopped me in my tracks. That was the moment I decided to find out what it was all about. That is what I wanted for my athletes.

If studied and utilized as the creators of the program intended, the 1x20 is a powerful tool, says @YorkStrength17. Share on XImmediately you realize that “1×20” is just the catchy name they gave the program. If studied and utilized as the creators of the program intended, it’s a powerful tool.

Laying a Foundation

The basis of our layering system is to develop the strength and full-body movement proficiency to be able to prepare our athletes for the heavier loads, increased volumes, and more-advanced training protocols that their training age and adaptation process demand. Our top priority is to always keep in mind that anything we do that doesn’t help make them better at sport probably needs to be re-examined.

As my lens began to widen on the sports first, weight room second philosophy, I truly began to recognize how the 1×20 system could take our process to a new level. The way I saw the basic principles of how to use the 1×20 was that we could add not only great depth to our athletic development model, but great width as well. We could use this program to reverse engineer every important aspect, every movement that our athletes would need to be the best at sport they could possibly be, and develop it slowly over a long period of time.

It’s universally recognized that we want our athletes to get stronger, faster, and more explosive. Many see the key to that in the performance of movements such as the back squat, bench press, power clean, etc. The big rock lifts done for multiple sets of 3-5 reps will no doubt build strength, but in addition to strength they can lead to compensation patterns that could eventually result in injury.

Jumping ahead in the development process also misses crucial development of the smaller muscles that will become the weak link if not addressed. Using the traditional barbell movements with higher intensity can be compared to putting a high-performance race car engine in my daughter’s 2007 VW Bug. That engine can be as strong as you want it to be, but if the tires, frame, shocks, etc. are not compatible, it will break down. The athlete is no different.

That breakdown may come when they are in high school, or it may not. One thing is for sure, if they don’t develop proper balance at some point, they will break. Even if it’s when they are in college or beyond, that blame can often be placed directly on the training they received as a young athlete. That being said, there is no perfect program and no way to prevent injuries. All we can do is provide the most complete program possible to build resilience.

[adsanity align=’aligncenter’ id=9064]

Why the 1×20 for Us

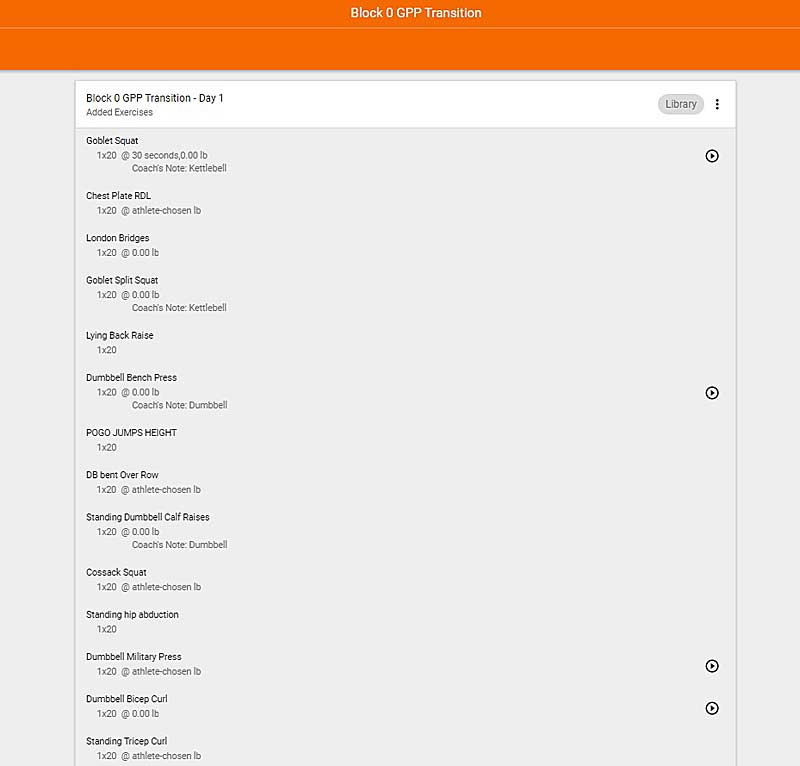

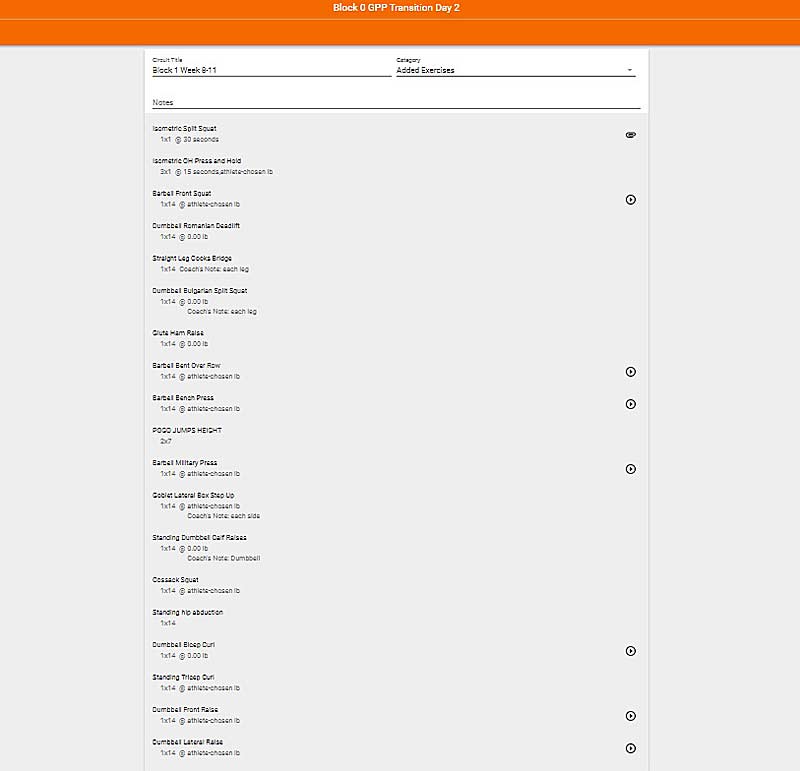

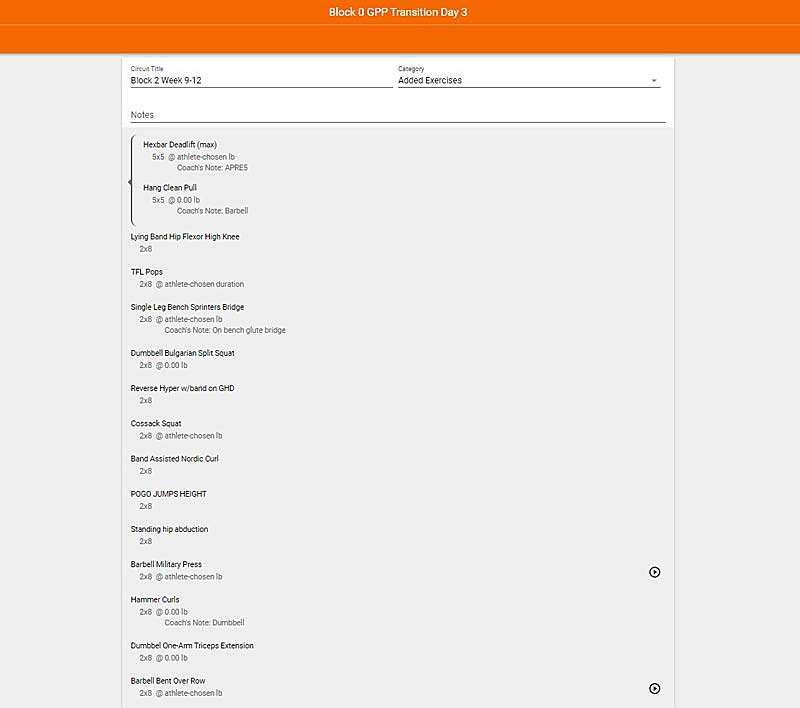

Using the 1×20 system allows us to design a path that adds depth to our progression system and gives our athletes a base of holistic strength that I believe will make them much more resilient than programs we have used before the 1×20. If we follow the program as designed, it is true general preparation from head to toe. It helps us with a smooth transition from Block 0 to our Block 1 and then transition to Block 2. As we advance in our Block 2, we eventually get to the point where the athlete uses a standard and dependable 5×5 program for those big rock movements with auxiliary movements working from 1×20 to 1×14, to 2×8, and eventually to 3×6.

Over 2-3 years, our athletes move from bodyweight movements through multiple levels of movements and movement variations that have all been reverse engineered from those we determine we will use at the top of our layering program based on transfer to sport. When the athlete is ready to move to our more advanced Block 3 program (wave periodization), each step has built on the next with multiple layers of progression and regression (when needed). It creates a fluid flow for our athletes year to year. Most of all, it provides the athlete with thousands of reps of developmental movements for every joint angle and muscle in a progressive manner in both movement proficiency and intensity. No other program I have found gives the athlete an opportunity to groove 18-25 movements a session, up to three times a week.

The 1×20 also gave us a unified developmental process that allows us to provide quality programming for all athletes, from those who show up daily to those we may only see a handful of times per year. Young athletes who I don’t see year-round and those we refer to as “drop-in athletes” were often a real conundrum for us. Using the 1×20 plan allows these athletes to jump in and out of the program without falling behind. Even if the movement variation is slightly different, every athlete in that layer will perform the same basic movements.

The 1x20 gave us a unified developmental process that allows us to provide quality programming for all athletes, from those who show up daily to those we may only see a few times per year. Share on XThe athlete who has done the workout 25 times will have advanced a great deal in load used, but the length of time spent on each layer ensures that the athlete who has only done the workout 4-5 times in that period can still step right in and train. It quickly becomes an athlete-led program that is very self-progressing. The learning curve is not as steep, and the rules of how we progress from a load perspective are very simple. Athletes master movements by repetition and begin to add great amounts of strength as they progress. The off-and-on athlete can still train with their peers who have trained consistently because the basic movement will be the same even if the mode/load or rep range changes over time.

The results I have seen while using this program have been remarkable, particularly with our female athletes. As I wrote in another piece discussing the unique experience of working with female athletes, in my experience, progressing load and intensity is often a challenge. This program gives clear directions on what rep range achieved will dictate adding weight.

This has been remarkable in practice. The rep range makes it comfortable for the athlete from a load perspective. It also builds confidence in adding weight and progressing. Going from 20 pounds for 20 reps to 40 pounds for the same number in just a few weeks (for example) is an increase in strength. It also puts the athlete in a state that helps take some of the fear out of progressing to 50 pounds for 20 reps or maybe 65+ pounds for eight reps later on. Those types of gains are very common with this program.

From a male athlete perspective, it has helped break the “daily max out” thought process that so many young male athletes bring into the weight room (which I have no doubt can limit progress). They now take pride in the weight they can get for 14-20 reps. When it comes time for them to drop to sets of eight and six, they will be proficient and strong. The gains in strength and, frankly, the hypertrophy that comes from this program with young males (in my experience) are remarkable.

From a velocity-based perspective, there are clear connections to why coaches who use this program experience such remarkable results. Athletes are exposed to the entire range of the force-velocity curve in each set. The lower load initially allows the athlete to move the first few reps with close to max velocity, particularly in the early parts of the program. As they progress through the set, they will hit reps for speed-strength, strength-speed, and eventually max strength, all in the same set but with 18-25 different movements.

I believe one aspect of the program that many aren’t aware of is that all assigned repetitions are meant to be a range. The athlete is taught that if it says “20 reps” that really means shoot for 20, but if you can do more, then keep going. Athletes will naturally force hypertrophy adaptation with the volume and the pace at which they are able to add load following this protocol.

I believe one aspect of the 1x20 program that many aren’t aware of is that all assigned repetitions are meant to be a range, says @YorkStrength17. Share on XIn our program, APRE is a major tool. We use the 1×20 protocols as a way to teach and progress our athletes to our APRE program (and eventually to our VBT level, which uses an APRE-like protocol). Using the APRE philosophy, we have set a range of reps above and below the target and tied that to a process that clearly lays out how and when the athlete should progress the load. This process mirrors our APRE3 and APRE5 protocols used in later layers. If you would like to know more details on this aspect of our modification of the 1×20, feel free to reach out to me.

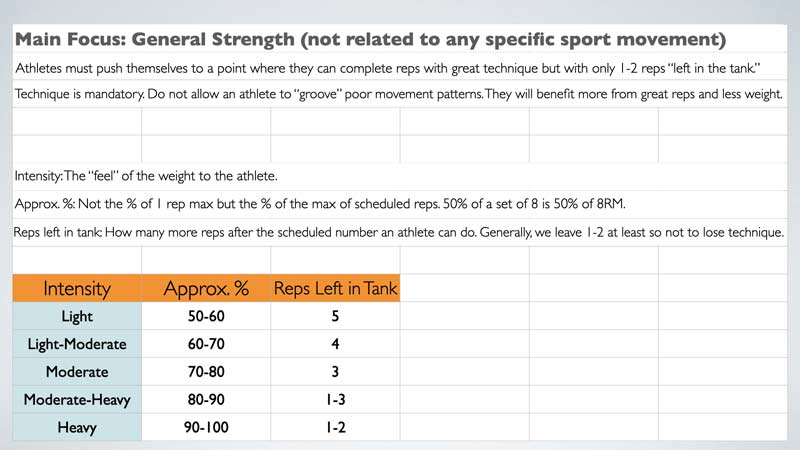

We also use an “intensity” protocol (see figure 4) that helps us progress our athletes to the “reps left in the tank” version of RPE that we use in later levels. Again, the sheer volume of practice they get with these ranges helps progress them to the “feel” of what we look for from a relative intensity aspect. Obviously, this can help us adjust individually or as a group, as our athlete monitoring system protocol dictates.

A Worthy, Evidence-Based Program

What you take away from this article isn’t that you should immediately stop what you are doing and switch to the 1×20 program. My real hope is that, even if you never use the program, you at least recognize it as less of a novelty and more of a viable way to develop an athlete. I feel at this point that the 1×20 is a kind of counterculture. I say this because I see a small group of coaches dedicated to the program having great success and touting its value.

You could take to social media right now, type in “1×20,” and see how many mainstream coaches attack and ridicule it. The thing is, I was once one of those attackers! I made the same mistake that the vast majority of the anti-1×20 crowd makes. They see “1×20” and don’t take the time to really look into the program to understand that a catchy name doesn’t define the program. In fact, the real magic is in the depth of progression you can add to any program.

The real magic of the 1x20 program is in the depth of progression you can add to any program, says @YorkStrength17. Share on XThere is no doubt that I am not an expert. In fact, I use a fairly modified version of the program. Our program uses the 1×20 protocol to build a deep base of total body strength and movement skill over a relatively long period. We use it to reverse engineer where we want our athletes to be and develop a road map that ensures we don’t waste an ounce of fuel on our trip to our advanced program. We also use it as a GPP for all our athletes for the four- to six-week period following the end of a sports season to reboot their system in preparation for the coming off-season.

I could point you to coaches from all levels, from high school to collegiate to private sector, who use the 1×20 program as more than a building block or GPP. The real secret sauce to this or any other program is knowing the WHY. If you understand the needs of your athletes and are willing to step back and take in that view from 30,000 feet, this program just may become for you what it has become for me. At the very least, I urge you to listen to the guys who are the experts, from Dr. Yessis to Yosef Johnson to Jay DeMayo, Jeff Moyer, and more. I will almost guarantee you this: You may not end up using the 1×20 program with your athletes, but you will see that it is a well-built, evidence-based program that deserves respect.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF