[mashshare]

Ryan Bracius joined the UW-Whitewater strength and conditioning staff in 2013. Prior to coming to Whitewater, Bracius trained some of the top high school area prospects, NFL players, and Division I athletes in a brief stint at Dr. Mark Turner’s Injury Armored in Aurora, Illinois.

In 2010, Bracius headed to Rockford University as the Head Strength and Conditioning Coach for football. From 2011-2012, he was the Director of Athletic Development for a variety of sports at Fit2Live-Athletic Development and a volunteer strength and conditioning coach for Olympic sports at the University of Iowa. Bracius is an NSCA-certified strength and conditioning specialist and USA Weightlifting sports performance coach.

Freelap USA: What makes your strength program different than other coaches’ programs in the university setting?

Ryan Bracius: Our programs at UWW are unique in that we implement the 1×20 system to drive the success of a multitude of sports, from football to swimming. Many have heard of Dr. Yessis’ 1×20 method, but few understand it. (I’ll go more in-depth on the specifics for question #4.) We clean, squat, bench, sprint, and jump—we just do our general physical preparation a little differently.

This could be why this program is scarcely used; to my knowledge only two or three coaches across the U.S. implement it. It is my hope in writing this to clearly, and simplistically, describe how we use this program to develop championship teams and record-breaking performances. I ask that people view what we do as more of a systematic approach to athletic development and less of an actual system.

Freelap USA: What is the purpose of your strength program and what you are trying to achieve?

Ryan Bracius: The goal of the program is very simple: to improve the athlete’s performance in regard to transference. This is a systematic process that is dictated by the time of the year each sport is in (i.e., phase/block). For example, in the UWW football program there are three phases (not including our transitional periods): general physical preparation (GPP), special physical preparation (SPP), and competition (C). Each phase has its primary, secondary, and tertiary goals, and each phase builds into the next in a smooth transitional fashion.

As you will see, there may be some overlap from one phase to the next. For example, an older athlete may enter SPP in May, while a younger athlete may enter SPP in mid-late June. Progression in this program depends upon what I see/measure, mastery of key movements, and feedback from the coaches on an athlete’s movement proficiency on the field.

I have outlined each phase/block below:

General Physical Preparation (GPP): January – May/June

- Primary Goal: Strength

- Secondary Goal: Aerobic

- Tertiary Goal: Explosive strength

Special Physical Preparation (SPP): May/June – August

- Primary Goal: Speed

- Secondary Goal: Explosive/reactive strength

- Tertiary Goal: Aerobic

Competition (C): September – December

- Primary Goal: Win conference

- Secondary Goal: Maintain speed

- Tertiary Goal: Maintain explosive/reactive strength

Freelap USA: What are some results you’ve gotten that stand out?

Ryan Bracius: Results speak louder than words; we all agree on that! However, what are we trying to achieve? For me, the goal is simple: Do we produce better athletes who contribute to wins and break records? While weight room numbers look great and are fun to have, do they necessarily change the numbers on the scoreboard? I always remember what Yosef Johnson says about results—do they “cut the check”?

If you have a pulse on college football, then you know Whitewater has been a perennial powerhouse for quite some time. Even though fluctuations of success happen often, Whitewater has managed to be a program to reckon with on a consistent basis, even amidst constant changes in the guard, such as losing athletes to graduation, financial hardships, transfers, and/or walk-ons. For example, transfers may be used to a different structure, and walk-ons may have a lack of preparedness. Despite these changes, our training has consistently prepared these young men for the highest on-field results.

Every year, I am able look back at the previous season’s data and refer to notes from the sport coach’s feedback I get from spring ball. This past winter training (2018) we had something special happen, mainly regarding the team’s relative strength ratios. As many of you know, there has always be a debate on how strong is strong enough, and how we interpret that. For us, this could mean that an athlete achieves a high relative strength ratio, or he can qualify for a more advanced means such as a velocity-based approach.

This past development cycle, the entire team hit averages of 1.89 for squat and 1.34 for bench. This is the highest ratio in our program’s history and indicates that we are strong enough and prepared to evolve. In my opinion, this should give the S&C community new insight into how to interpret weight room numbers that matter.

We have implemented the 1x20 program with the men’s and women’s swimming programs since 2013. A stopwatch sport such as swimming is the ultimate ‘cut-the-check’ test. Share on XBesides football, I have implemented the 1×20 program with the men’s and women’s swimming programs since 2013. A stopwatch sport such as swimming is the ultimate “cut-the-check” test, in which time is the quantitative measure! For instance, there are currently 47 school records hanging in the pool and, after the 2017-2018 season, 41 of those records have been broken multiple times! Breaking 41 school records in five years is enough quantitative data to make the conclusion that our program is doing what it is supposed to.

Freelap USA: How do you progress the strength section of your work?

Ryan Bracius: Quite simply: 20’s to 14’s to 8’s to 8+14 and even 2×8 + 14. Boring? Yes, probably. Effective? Extremely! The type of strength we target is, again, dependent on the time of year/phase/block, etc. Velocity-based training (VBT) or dynamic effort (whichever term you prefer) is in the equation in some form throughout our training year.

For example, jump training can be thought of as dynamic even without demonstrating true plyometric action, but it is still a dynamic effort intent. In fact, our jump training may be our signature, as we train various jumps from extensive to intensive year-round, which may be more than any college football team in the country.

Looking at the time of year, here is a general breakdown of what it may look like.

General Physical Preparation (GPP): January – May/June

Winter – Weeks 1-7/8* (Monday/Tuesday: Lower Body – Tuesday/Friday: Upper Body)

Weeks 1-4:

- Special Exercise: Knee Drive/Paw Back, 1x20ea – Everyone

- General Exercise: Bench Press/Back Squats/Rows, etc., 1×20 – Everyone

Weeks 5-8:

- Special Exercise: Knee Drive/Paw Back; Forward & Side Lunge added Week 7, 1x14ea – Everyone

- General Exercise: Bench Press/Back Squats/Rows, etc.

1×14 – year 2+

1×20 – year 0-1

*May be a seven-week winter period depending on last season’s outcome and academic calendar.

Spring Ball – Weeks 1-5

Spring ball is where we start to make a transition from winter (GPP) to the start of summer (SPP) training. I use these five weeks to make a smooth transition from one phase to the next. There are two differences in spring ball: exercise selection and increasing intensity.

During the winter, we may do RDLs, while during spring ball we will change RDL to glute-ham raises. As you will see, the reps stayed the same at the start of spring ball, but the movement changed. At the end of spring ball, the movement stays the same, and this time the reps change.

Weeks 1-2:

- Special Exercise: Knee Drive/Paw Back/Forward & Side Lunge, 1x14ea – Everyone

Weeks 3-5:

- Special Exercise: Knee Drive/Paw Back/Forward & Side Lunge, 1x8ea – Everyone

Upper body jumps are introduced at the start of spring ball.

-

Weeks 1-3: Clap Push-Up Jump

Weeks 4-5: Total Body Push-Up Jump

Weeks 1-3:

- General Exercises: 1×14 – Everyone

Weeks 4-5*:

- General Exercises: 1×8 – Everyone

*VBT Bench Press is introduced at this time.

I did not show what I call my “special population” athletes. These athletes are the ones who are what I term as “strong enough”! That’s right—they do not need any more strength in the general sense and may risk getting slower or less powerful if they continue to push up weight room lifts. These are the guys who squat 2.5x body weight and bench 1.5x body weight.

During the winter period, this group may be doing High Box Step-Ups or Quarter Squats, or even make the switch to VBT. During spring ball, they may make the switch to VBT or Quarter Squats. It all depends on what they did during the first 7/8 weeks and test outs.

Special Physical Preparation (SPP): May/June – August

The conclusion of spring ball leads us into summer and the start of our SPP phase. The previous five weeks provided us with a very smooth transition from GPP to SPP training. This is not to say we abandon all GPP work, but the emphasis and primary objective changes.

When you make the change to SPP, you may see a similar change as we did from winter to spring ball, when RDLs change to glute-ham raises and the reps change. This time, the change is most noticeable in our fieldwork. Jumps—both lower and upper—start to go from extensive to intensive to plyo; speed training starts to have a more-traditional look (short to long); cutting drills make a change to a reactive cognitive approach.

The 1x20 is about small, smooth changes in either exercise selection or volume & intensity to get the desired outcome. Share on XAs for the weight room, reps will change again as we shift to more VBT. A good example is the glute-ham raises, which may have been performed more for strength during spring ball, but now become explosive glute-ham raises. Again, it is more about small, smooth changes in either exercise selection or volume and intensity to get the desired outcome for that given phase.

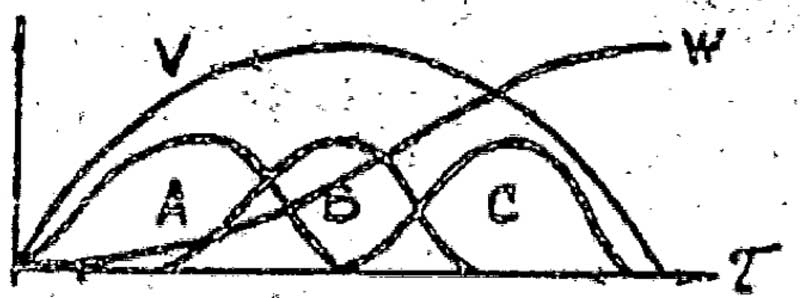

Many of you may be familiar with Dr. Y. Verkoshansky’s picture illustrating the conjugate sequencing system of blocks A, B, and C smoothly overlapping each other. This picture is a perfect representation of Dr. Yessis’ 1×20. The 1×20 is about small, smooth changes in either exercise selection or volume and intensity to get the desired outcome. In simpler terms, the goal is to improve the athlete’s performance with the smallest dose possible to elicit a training effect. As Henk Kraaijenhof has said, “Give athletes what they need, not what they can handle.”

My hope in writing this is to clear up any misconceptions of what Dr. Yessis developed more than 30 years ago. Most misunderstandings about the 1×20 peg it as a system. This is completely false! Just as the human body is an evolving organism, 1×20 is more of an evolving concept and thought process than it is a system. Dr. Yessis created a “system” that is based on a collection of scientific principles, and these principles work within the laws (of the body), not around them.

Boring? Yes, probably. Effective? Extremely!

Freelap USA: How do you implement conditioning alongside the 1×20 ‘system’?

Ryan Bracius: Being D3, logistics is the biggest challenge we have! We do not have athlete-only facilities or multiple indoor fields/tracks. In-season sports, such as baseball and softball, have first priority of our fieldhouse for practice. You have to remember that this is Wisconsin and there is a ton of snow on the ground! What we do have is the volleyball arena, which gives us 60 yards of length and about 40-45 yards of width to work with.

Therefore, a lot of our off-season conditioning is dictated by weather and scheduling. As I wrote about earlier, the secondary goal in our GPP phase is to build a large aerobic engine. Ideally, I would like to use the mile progression; generally speaking, starting at 1600 meters and work down to multiple 400-meter runs. However, I have to work with what I have! Using two days a week (Tuesday and Friday), each day we work on a different aerobic quality. Tuesday is alactic capacity and Friday is aerobic capacity.

Tuesday – Alactic Capacity

Alactic capacity work is done using the 30- and 40-yard shuttle between 15 and 20 total reps in a given session. There are days when we will just use the 40-yard shuttle, and there will be days when we will use both the 30- and 40-yard shuttles concurrently.

-

30-yard shuttle

- 5 yards – back, 10 yards back = 30 yards

- Rest intervals 30-40 seconds

-

40-yard shuttle

- 5 yards – back, 10 yards back, 5 yards – back = 40 yards

- Rest intervals 40-50 seconds

Using the 30- and 40-yard shuttles allows me to keep a large group of different positions within the 10-15 second range.

Friday – Aerobic Capacity

Aerobic capacity work is done using 106-yard tempo runs for 16 total reps with 45 to 60 seconds of rest in between. In between the runs, we will do some active rest in the form of ab exercises and push-ups. As I stated a few paragraphs ago, in a perfect world we would use the mile progression; but 16 106-yard tempo runs equals 1,696 yards or 1,550.82 meters—just 50 meters short of 1 mile.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

[mashshare]