Overload/Adaptation. We all know what it means, but not enough attention gets paid to either. This article will talk about the overload part of the relationship and how to manage progressions to optimize time and performance improvements.

Are you familiar with the story of Milo? The myth is that, as a small child, Milo would go out every day and lift a calf. As the calf grew, Milo was lifting a larger and larger animal until, as a grown man, he was lifting a bull. This demonstrates the lesson of small incremental overloads over a long period of time leading to great strength gains.

Properly timed progressions are the quickest way for athletes to make gains, says @jdevore1. Share on XMy experience has shown me that properly timed progressions are the quickest way for my athletes to make gains. I believe that all the fancy exercises and technology in the world cannot compete with a great understanding of how to progress an athlete.

Look to Make Incremental Gains

I also believe that a great coach’s real value is in the gift of time to their athletes. While most people think the value is in injury prevention, athletic performance, sport-specific performance, etc., all of these things provide the athlete with more TIME. It is a gift of more productive years at the highest level of performance. If an athlete is injured they cannot train, so poor program design wastes an athlete’s productive years (even if they make some gains). Could the gains have been greater? I see my role as a coach to realize the greatest amount of sustainable genetic potential of the athletes I am charged with training without injury.

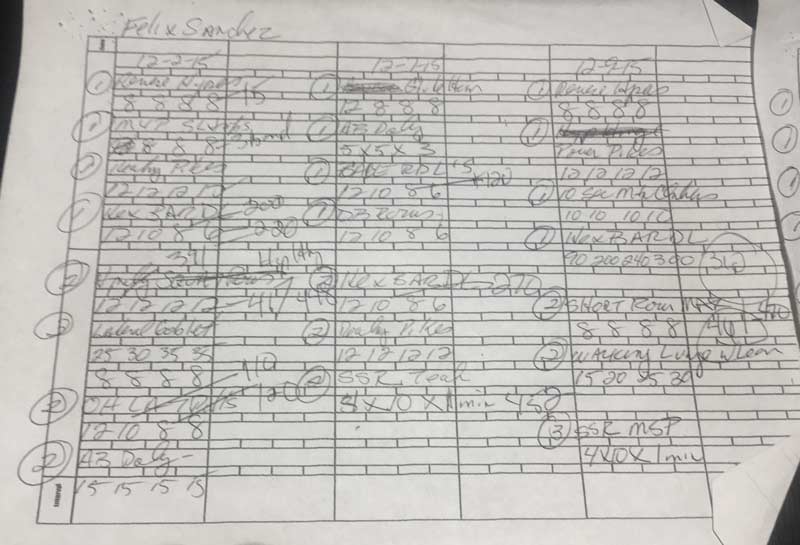

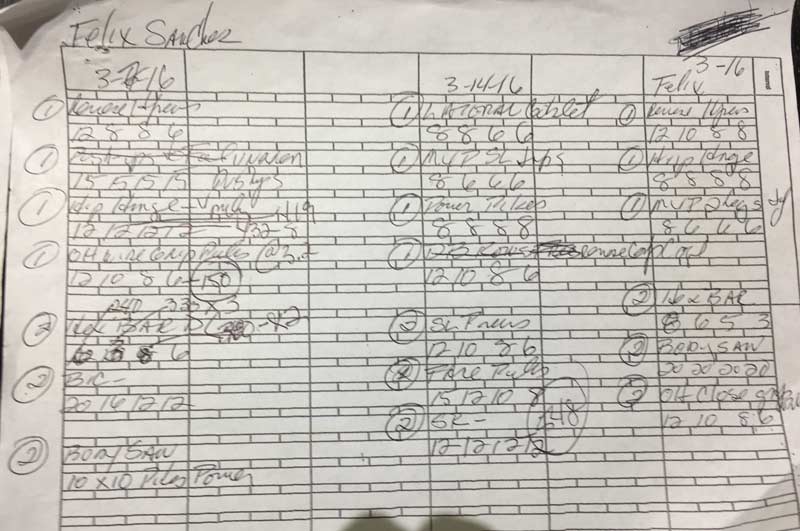

My understanding of the science and the athlete’s body allows me to give the athlete much greater performance in their most productive years of play. Athletes are dynamic, which is the reason monitoring how they progress is so important. I have a hard time understanding a coach that does not write things down. I always write notes to myself and, even though there are plenty of spreadsheets available to use, I still rely on my notes to help me understand the dynamic nature of training. These notes allow me to learn better ways to make progressions.

I look for incremental changes in my design to produce greater and faster marginal gains that, when added together, create what I call “tipping point” fitness.

Years ago, when the Raiders were in the Super Bowl, I was lucky and got to train Regan Upshaw in that off-season. He was one of my first high-profile elite football players. When I trained him, he had been in the NFL for 11 years. I had never worked with a defensive end at the time, so in my evaluation of him the first thing I did was look at what my primary objective would be if I improved him as a player in the gym. If I could create an athlete who, when the ball was snapped, was immediately in the quarterback’s face, I would be a tremendous coach.

While that is an impossible task, I looked at what percentage of that objective I could achieve and worked backwards. With that mandate in mind, I began to tear apart everything he did once the ball was snapped. What did he require physically to perform at his best based on the needs of the position? I would use the tools of exercise science and training to reduce the time it took him to get to the ball.

I started by looking at his stance to determine how I could reduce the time of his first movements in any direction. We found that he had a very long rear foot stance. This was comfortable, but slow. His time off the ball was about 30% faster if we brought his rear foot up closer. I then looked at what I needed to do from an exercise physiology standpoint to better accommodate this new foot position, as it was initially awkward. Adding more hip flexor mobility made this new stance more comfortable for him.

This was my first incremental gain and it was a tipping point for him. The time immediately after the snap has much greater value to a lineman. During the Super Bowl, I saw him line up on the ball and then move his back leg forward and it put me on the field. I was elated. Of course, we then moved forward to evaluate all the other physical needs of his position. With great athletes, marginal gains add up to big performance gains.

Without incremental #overloads on a regular basis, an athlete will make little progress, says @jdevore1. Share on XKeeping that in mind, what have I seen as one of the greatest influencers on really fast results without injury? Is it a better understanding of technology, pre-hab, program design, exercise science, mobility, stability, exercise selection, Olympic lifting skill, coaching capabilities, etc.? The list goes on and on. I do not discount the importance of having a basic understanding of all these tools.

However, after a decent understanding of these tools, you make the greatest impact by determining when and where to progress athletes. The great thing about this skill is it relies more on your ability to pay attention, listen, and observe than all the science in the world. Without regular incremental overloads, you will dramatically slow progress! I will say that again: Without incremental overloads on a regular basis, you will see little change! Milo would have been puny if the calf did not grow.

When, Where, and How to Progress Athletes

After high school, athletes today have short off-seasons but you may find blocks of training time that are long enough for you to make an impact. Let’s say an athlete is 19 when he starts college. According to the NFL Players Association, the average career length is about 3.3 years. The NFL claims that the average career is about six years (for players who make a club’s opening day roster in their rookie season). If this is the case, and each player has about eight weeks when they can train consistently in the off-season (I am being generous), the time disappears fast.

That is a total of four years in college and about six years in the pros. So there are about 80 weeks of total off-season training time when players can really make gains. Therefore, if you believe that adding 2.5 pounds to a lift is insignificant, you are really missing the boat. I tell my athletes that proper progressions are like compounding interest for retirement. At first, it does not seem like it is doing much. Then, you suddenly look at the account and there is significant money in it. Building an athlete is similar. Sensible, regular progressions compound and increase in value over time.

Proper #progressions are like compounding interest for retirement, increasing in value over time, says @jdevore1. Share on XAny unproductive time is costly. One week a year of lost gains in fitness is 12.5% of the total time the average player has in an NFL career after high school to make gains. Two weeks lost is 25% of potential lost for the athlete. This is devastating when you know that the difference between being a franchise player and getting cut can be very small percentages in performance at that level.

The problems that arise in progressions are due to the human body being a dynamic mechanism. This attention on progressions needs to be on strength, but even more so on power and any metabolic conditioning you may perform with your athletes because there is a bigger risk of overtraining these metabolically taxing exercises. Progressions are even more important as the athlete becomes better and better. This is because overloads need to be bigger or more intense to get a change in performance as the athlete gets fitter and fitter.

When progressing an athlete, you need to consider these factors:

- Time: How much time do you have to train the athlete?

- Maturity: How long has the athlete been training at this level?

- Chronological age: This will have an impact on recovery time. It does not mean an older athlete cannot recover quickly, but you need to keep age in mind.

- Recovery and adaptation time: This is more of an individualized evaluation.

- Fatigue: CNS (central nervous system)/Peripheral (muscle-specific)

- Current level of relative fitness: What level of fitness are you starting with? The fitter the athlete, the more important the progression. An unfit athlete will make gains quickly with most types of stimulus. However, the fitter athlete must have a more focused design.

- Biomechanical issues and impediments: Until remedied, this may limit your ability to make big progressions. However, injuries have helped me become a much better coach, by figuring out ways to improve the athlete in areas that have been neglected for long periods of time.

- Past or recent injuries: Athletes have injuries. How far away from the injury is your training? Always remember it can impact your progressions—it is equivalent to driving a high-performance car fast on bald tires.

- Baselines to establish overloads: Poor baseline analysis wastes a great amount of time as you do not get to an overload level fast enough.

- Mental toughness: Most athletes hate to train things they are not good at. It is like getting a kid to eat their veggies. Sometimes you have to figure out how to make them think it is dessert.

- Winning a workout: Athletes want to win. If you do not create little victories in each workout, morale decreases and progressions are more difficult as you will see breaks in training.

Periodization: When and How Much?

What is the most effective method of progressing an athlete? When, how much, and how often is the science of periodization. In the 1960s, the Eastern Bloc employed 10-year periodization. They would identify a candidate in their early youth and then start the process, which meant they looked at progressions over a very long period of time. Tudor Bompa is considered a pioneer in the study of periodization and he brought much of the Eastern Bloc training methods to the West.

Overload/Progression: A simple definition of a progressive overload is anything over the norm that creates a stress large enough for the body to make an adaptation.

Some examples of overloads:

- Load/Intensity: More weight and power output. Higher velocity, and higher percentages of maximum output.

- Volume: Time of output, more reps, more total sets.

- Rest/Density: Rest between the sets; rest between the reps. Most do not think about rest between reps. I utilize this method very effectively in training for efficiency of power production.

- Tempo: Speed of a movement

- Metabolic load: Anaerobic, glycolytic, and aerobic. What are the fuels needed and rest to recovery ratios?

Periodization is just the design of the overloads and rest to elicit a desired outcome. This design will impact progressions in your training. Typically, periodization is organized in blocks. The blocks cover different energy system needs or physiological objectives: strength, hypertrophy, strength endurance, power, power endurance, etc. You typically have a microcycle, mesocycle, and macrocycle. The microcycle is the individual objective of a workout, the mesocycle may be three weeks, and the macrocycle is the overarching longer term strategy.

I have studied the work of Verkhoshansky, Siff, and Bompa on the subject. The problem with most of the original periodization models is they were developed for weightlifters or competitive Olympic lifters whose sport is their training. As a strength coach, and a competitive cyclist, I have learned much about how periodization impacts aerobic performance on the bike. How do you take the lessons of these progressive overloads and apply them to a particular sport for power and strength? You are not trying to build weightlifters most of the time, but you are trying to improve movement and power by way of the weight room.

Endurance athletes are much better at periodization than most team sport athletes. The endurance athlete’s seasons are long and there is often a need to peak for particular events, which lends itself to an effective periodization. With a field or team sport athlete, there is more of an overall need for fitness and then some peaks throughout the season that are dictated more by the coaches of the sport itself, not the strength coach. Once the season starts, it is more play and rest with lots of maintenance to minimize de-training. However, the principle behind periodization is really just a physiological management tool for overloads and adaptation so that the athlete is at their peak when it is most valuable.

I think the takeaway from all of these periodization programs is that you need to build a solid foundation of fitness that addresses the need for the sport. This allows the athlete to progress from this foundation with higher and higher intensities and overloads that have a low risk for injury or overtraining, and then build on this fitness throughout the season through maintenance workouts and competition.

There are many different types of periodization and I will not go into detail on all of them here. The two most common are linear periodization and undulating periodization. Linear breaks out blocks of time, with objectives in each block: hypertrophy, strength, strength endurance, etc. Each block has a focus and you progress through the blocks. Undulating periodization has multiple objectives, and peaks and troughs more often within each of the objectives.

I like Louie Simmons’ conjugated periodization system for my strength and power training the best (it’s much more undulating in nature), as you can apply the principles much easier to different sports and levels of athletes, and it fits well into a commercial center. Collegiate athletes have mandatory practice, which makes some aspects easier. The undulating periodization system allows me to better and more easily address the unpredictability of an athlete’s time, and more rapidly progress athletes that may have faster recovery times.

Viewing Physiological Requirements as Windows

I label my personal system, “Training with Windows.” I am a visual guy, so I like to visualize my overall training design for an athlete as if I was looking at a wall of windows. Each window represents a particular physiological requirement for that particular sport. Remember, most athletes we train are not competitive weightlifters, so the ability to have multiple physical qualities is very important. The windows reflect the needs of the sport at the highest level of performance. During the year, some of the windows are wide open and some just slightly open. The only time they are all wide open is during competition. I spend a lot of time identifying the needs of the sport and what skills the athlete comes to me with, and then determine the gaps for gains.

My system is ‘Training with Windows’—where windows are the needs of a particular sport and position, says @jdevore1. Share on XFor example, let’s say I have a competitive high jumper. Some of the primary physiological windows for their sport would be: lower body strength, lower body power, mobility in hips, mobility in back and shoulders, dynamic core, stability and power, t spine mobility, drive leg power and strength, high rate of force development, hamstring strength and eccentric loading capabilities, strength endurance, speed strength, and knee stability. These are some of the primary windows I would evaluate.

Most of these are obvious, but I need to determine the current physiological infrastructure of the athlete that I need to improve in order to address these needs and progress them. The athlete needs to be able to perform a large number of strength exercises with large amounts of weight. In addition, they need to have enough mobility to handle the upcoming training for power. I look for correlation coefficients to the act of jumping. A correlation coefficient is the amount of influence one variable has on another variable. Your best squatters are typically not your best vertical jumpers, but squats will help improve a vertical jump. Therefore, squats are part of the program that will help support the power training to improve vertical jumps.

An extreme example of this concept would be forearm strength and high jumping. I would say there is a very low or nonexistent relationship (correlation coefficient) to high jumping. In fact, if an athlete’s forearms got too big, they would add unnecessary body weight, which would negatively impact the athlete’s jumping height. However, without good wrist mobility and forearm strength, power cleans are difficult to execute. So, there has to be a window opened to this skill of wrist mobility and shoulder integrity even though it is not a primary window.

I determine the size of the window I utilize by the relationship it has directly or indirectly in supporting the final requirements of the athlete for the sport.

Using the idea of these windows, how do we design and monitor progressions?

As I said when it comes to strength and power, I like the conjugated training system because it regularly addresses all the needs of the particular lifts, but with emphasis on particular areas at different points in time. This also supports my idea of little victories and keeping the athlete engaged. Remember: Athletes do not like doing things poorly, so you need to balance these skills. My high school athletes want their biceps to look good when on the field. The need for biceps may be very low in their respective positions, but I have no problem killing their arms and sending them out of the gym with a big pump from time to time to give them a win.

Following through with my windows metaphor, I never completely close the window on any required skill. I may, however, just crack the window open a little and have another window wide open, while changing the focus so that I can marry the individual’s progressions to the needs and weaknesses in their performance skill set that may already exist. If an athlete is monster strong on deadlifts and squats, what is the added value of more squats if the position or sport they play does not require greater lower body strength than they already possess?

Therefore, I may crack the window to maintain their lower body strength, but shift my focus and time elsewhere. I may skip ahead and go to maintenance on these exercises and jump right to improving the athlete’s power. This saves me valuable training time that I can gift to the athlete. This is also the reason I am not as fond of systems of training with elite athletes.

I believe in sport that all roads lead to power. In some cases, it is a high output of power for a few efforts (high jump, shot put, etc.) However, most sports require multiple efforts of power in different planes of movement. It is not the highest output of power that wins, but the ability to hold the highest percentage of that power the longest in a competition.

Designing the Workout

Once you establish the windows (needs of a particular sport and position) and establish what baseline skill set your athlete possesses (how big are their current windows relative to the needs of the sport?), the next step is designing the program that will best address these needs and gaps that the athlete may have and that are most important to change. This is your overarching program design to make the improvements necessary to bring your athlete to their highest level of output in the time you have. I call this inter-workout design.

Within the workouts, we also have intra-workout design. This is where I most often see time wasted on poor progressions.

My goal is to progress the athlete to the greatest overload as fast as possible without any risk of injury. I do not want to waste sets, reps, or a workout because I did not get the overload I wanted. Time is where the value exists. Every coach will say if they had more time with the athlete, they could make bigger gains. This type of analysis can give you more time.

Time is where the value exists, and this type of analysis can give you more time, says @jdevore1. Share on XThe first thing I do is set a primary objective for my workout; e.g.., I am going to get a max in the deadlift or bench, or bump absolute power. The primary objective may also be to rein in the athlete so that I get the big lift later in the week. This primary objective is the win of the workout. Then, if you have a hiccup (which you always get), you can still see if you can accomplish your primary objective. Sometimes you just can’t get an overload, but by going in with the objective, you know what direction you want to head in. You also know that today may be best suited for active recovery, because if you try to force the overload at a subpar output you just dig the athlete into a hole and risk overtraining.

You can set up intra-workout progressions in a number of different ways. They can be arbitrary from week to week, with you just setting an increase in weight that is fixed from week to week or a percentage increase week to week. This may work better for individuals that are new to lifting or have not been in the weight room for many months. The progressions will usually be bigger jumps as the athlete gets back into the lifts and the body makes a more rapid adaptation back to the previous normal. The athlete has been here before, and you just work on technique and see if there are any biomechanical issues that need to be addressed. Therefore, this transition time is not a real improvement over where the athlete was at the start of last season.

You can also progress week to week and make changes based on the performance the week before. I like this with more mature athletes and it may work well in a bigger group, too. This can be on a fixed percentage or perceived exertion by the athlete. If you use perceived exertion, you have to educate your athletes on what this means or you will not get the output you desire. My goal is to reduce what I call “wasted” reps and sets and workouts. I want training, not exercise. Exercise is a component of training but may not contribute to moving the needle forward.

I use a rep scheme that allows for the dynamic nature of how an athlete feels. It is based on past lifts, but not wedded completely to them. The past lifts act as a guide. I overlay this with trying to have max lifts in one or two exercises in each workout. I monitor the type of lifts so that the athlete doesn’t do a squat 3 rep max and deadlift 3 rep max in the same workout or on back-to-back days. I am careful about designing the workouts so that recovery time is adequate. These could be an upper body and lower body, pulling or pushing maxes on the same days of the week.

It is also dictated by how many days in the week I get to train the athlete. If you get the athlete more often, you can be more creative with the maxes. This would be similar to the conjugated system. I, or one of my coaches, will observe the lift and try to progress the athlete based on a previous week’s lift, but at the same time take into account the possibility of a fitness bump during that workout. We know that, as athletes get fitter, jumps in fitness come slower and less often. I want to take advantage of a bump as soon as it takes place, not a week later!! This is really important and the reason I like notes. With notes, you can immediately go back and see what the last max lift was and the date it was executed. You will also start to see patterns in the time between max lifts for different athletes.

The Workout:

I start with a check-in set, which is typically 10-12 reps. I want to see how the athlete feels, and it is also a way to reduce injuries. The more days of the week the athlete trains, the lower the rep count can be on this set as the athlete is more in tune with how they feel. If you have bigger gaps between workouts, you may do two of these sets. You could look at this as a warm-up to the bigger lift to follow.

If I see any issues with form or if the athlete just feels weak, we progress accordingly. If my objective is to get an overload with a heavy lift, then I want to get there as soon as possible so I do not hinder my ability to overload with too many preceding sets and too much volume. Some athletes are more comfortable with bigger jumps in weight. The next set will typically be six to eight reps. I like the range of two reps as it gives me, my coaches, and the athlete some flexibility and still feel success. I always tell my athletes that I want to target the lower rep range if possible. This means that the sixth rep should be about all that they can accomplish. If you see that it is too light, do not do more reps. Just make a bigger jump on the next set, so as not to add unnecessary fatigue that may compromise you getting an overload.

My next set is typically three to five reps and the last set is two to three reps. Each set will have a bump in weight with the target in mind. The range of the reps gives us some flexibility in targeting. If I can get a 2.5-pound increase in weight, I am going to get it. Do not discount the smaller increases as having little value. On endurance days, the smaller increases are also of great importance and are sometimes overlooked. You want the increase in total volume on these days, and you must allow the body to get the weight on the bar. This method requires the coach to be more observant of the athlete in the lift, or to educate the athlete on the goal of the rep scheme and progression if the coach is not there to add value and monitor them.

I also am very cognizant of the athlete’s level of athletic maturity and I will typically look at “max” lifts for a novice differently than for a seasoned lifter. A less-mature lifter may have six to eight reps “max” as the top end while an elite lifter may have one to three reps.

Greater Improvements, Faster

I have seen great technical coaches get poor performance results from their athletes because of poor progressions. You need less Instagram moments and more focus on what really adds value and cannot be seen in a photo. My belief is that, with a few solid exercises and great progressions, you will make much greater improvements faster than with any other form of training. It is a dynamic process that requires a coach to pay attention and figure out ways to lead the athlete to obtain the greatest overloads without injury or overtraining.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF