[mashshare]

Recently, something came out of my mouth that would probably surprise most people that know me. I told a colleague of mine, “If I ever had the chance at some point in my career, I’d take a job coaching just female athletes.” This comes from a person who got his start coaching football and only running a strength program because I was the staff “meathead,” so you can imagine the looks of surprise I received.

After spending a good portion of the last 10 years working with female student-athletes, I’m willing to say with conviction that I never would have thought of making that statement before I began working with female-athletes. I bet if you are a coach reading this and had a similar career path, you probably agree with me completely. Those of you who may not have had the chance to work in-depth with females were quite possibly taken slightly aback. I know I would certainly have at one point in my career. What changed my mind? Why would I suddenly be willing to give up the “crown jewel” of many programs—varsity football—to work with just female athletes?

It’s simple: Because I experienced “training like a girl” firsthand.

Is There More to Strength and Conditioning Than Just Football?

My path to strength and conditioning is one paved by the sport of football. Football is why I first lifted weights. Football is why I went to the college I did. Coaching football is originally why I got into the field of education. Why would I even consider working with only females as a career option?

Working with football and other male student-athletes is great. I don’t want to present this as if I do not enjoy that part of my job. In fact, the majority of my time is dedicated to working with our football program. In my current position, football is the only sport I see every day of the school year and four days a week all summer. I basically spend about 48 weeks a year with that group. Football players will spend more time with me than anybody else at the school. Because of that, and the level of things I can progress football to, it’s really the “crown jewel” sport of our program, as it is at many places.

I enjoy the clanging of the weights, the vocal nature of the weight room, and the overall “meathead” environment of the room that we get with males, particularly with football players. From a motivational standpoint (as a former male athlete), the loud, high-energy, “hoot and holler” culture that many football sessions include is definitely invigorating.

My first experience with female athletes in a team setting was quite an eye-opener. I went in with the mindset of “athletes are athletes.” Of course, this is partly true, but not without caveat. What I quickly discovered was that female athletes aren’t as dependent on “emotional” motivation. They needed (in my experience) much less of the “Ric Flair” version of me than football players did.

I quickly discovered that female athletes didn’t need as much emotional motivation from me, but more reassurance and analytical reasoning, says @YorkStrength17. Share on XI also realized that there was a laundry list of nuances and both verbal and nonverbal communication that brought out the best in our female student-athletes. What I came to understand was that our female athletes still needed my high-energy style and would welcome me as a coach. They just needed a more reassuring, analytical, and sometimes (but not nearly as often) excitable version of me.

My Early Education and Learning Experience

My very first group of female athletes was the volleyball team at Piedmont High School. When they first came to me, I asked them to take a knee and please put eyes on me and listen. An amazing thing happened—each of the 20 or so young ladies immediately took a knee, put their eyes on me, and listened to every word with their full attention. At that moment, I knew that although there would be challenges, coaching female athletes would also be an extremely rewarding experience.

Although there were many physical and programming challenges that I would need to wade through (each will be discussed later), my first real obstacle was getting around coach and parent misconceptions about strength and conditioning. Several of the most prominent things I heard (and often still do) were the following:

- “I don’t want my athlete/daughter lifting too heavy.”

- “We want to tone their muscles, not get them big.”

- “We don’t want our athlete/daughter to be doing what the football guys do.”

- “I’d like to just do our running at practice. We really need to be in shape.”

- “I don’t need bulky athletes, we want long, lean, and athletic.”

That is not a comprehensive list (I’ve got limited space!), but it covers most of the major issues I run into with female athletes. I won’t go into detail with my answers to these questions in this post. I assume the readership has faced many of the same questions. Obviously, there are many female sport coaches who absolutely understand the science of sports performance. There are many parents who also get it. However, if you coach female athletes for any length of time, you will run into similar situations, I assure you.

The most effective way to deal with these questions is through education. The easiest thing to do is ridicule. That isn’t the right approach, however. This specific situation is very unique. Most, if not all, football coaches played the sport in a culture of strength and conditioning. It goes back decades.

The fact is that we have not had a long-enough run of widespread female athlete participation in organized sports performance training to have immersed all coaches or parents into that lifestyle. Neither group questions us out of spite. The questions come from legitimate concern for the well-being of their child. The most effective path for us as professionals is to educate and reassure.

As I’ve said multiple times in the past, a well-educated coach and/or parent is a very powerful ally. As sports performance professionals, we all know that the vast majority of females have little to worry from the fear of “getting too big” because of the hormonal differences in the sexes. It’s our job to explain and provide evidence to show coaches and parents whose background is not in sports science or performance why we do what we do to help the female athlete improve their performance. Take the time to cover the basics of human adaptation to stress and how we train energy systems specific to their activity.

I learned the most powerful tool in my toolbox is the question: “What exactly are you hoping to accomplish when your team walks into the weight room?” Most sport coaches can clearly answer that: “get faster,” “get stronger,” “be more explosive,” etc. As the sports performance professional, we can then provide the path to those goals while educating at the same time.

Working with the Athlete, Not a Stereotype

Female athletes come at you with a much wider range of experience than most male athletes (specifically football). I noticed that almost immediately after my meeting with that first volleyball team. The percentage of males exposed to some sort of training at a young age is quite larger than females. Male athletes often grow up talking about how much they can bench or squat. Many of the female athletes I see come to me with almost zero exposure to strength training. I count that as a blessing.

Many of the female athletes I see come to me with almost no exposure to strength training. I count that as a blessing, says @YorkStrength17. Share on XAnybody who has worked with football players knows the challenge we face when trying to “slow cook” our athletes. The battle to not allow the male athlete to “load dysfunction” is a big one. In fact, it has been my suggestion for quite some time that schools change the course name of a “PE/Weightlifting” class to “PE/Sports Performance.” That would at least set the tone and eliminate the “This is weightlifting—when will we be lifting weights?” question we inevitably get at the start of a new school year.

The issue with our female athletes is often the exact opposite. If I would allow it, 90% of our females would load about 30% of a 1RM on a bar and do 3×12 reps for four consecutive years. This may be a slight exaggeration, but that battle is just as real as the one with the males. The inexperience of many females is an advantage in that battle. We can spend the time early in the process to “slow cook” using little to no load.

The majority of female athletes practice an acute attention to detail we often don’t find in male athletes. This allows us to “move well” before adding load, says @YorkStrength17. Share on X“Mastering the Ordinary” is a motto for our program. One of the great things about the majority of female athletes is they actually practice an acute attention to detail we often don’t find in male athletes. This allows us to “move well” before adding load.

As that initial volleyball team proved to me, females are often a joy to coach because of the attention they pay to you. This is also a powerful advantage for coaches. Move slowly and explain why and how each movement will benefit them. Explain the “why” behind what you ask of them.

I’ve found giving females explanations is a very effective tool. Once the athletes are ready for some weight, most will trust you because you have explained the process. “Buy-in” is a bad cliché, I know this. However, another blessing of coaching females is how easily you can develop that “buy-in” through this process.

I mentioned in an earlier post how we use velocity-based training at a much earlier time with females. Males are easy to motivate to put increasingly heavy weights on. Females are much more easily intimidated by a number. Any of us who tells a 105-pound athlete to put more than her body weight on a hex bar and stand up with it can attest to that! VBT gives us evidence of exactly how heavy that weight actually is for that athlete. I can show her a chart that proves what she thought was her max that she moved at .81 m/s is actually far from it.

Another area that separates coaching females from coaching males is group interaction. In my experience, many times “ego” and the drive to be the “alpha” can lead to some very selfish behavior from male athletes. It can be very frustrating to have a plan for “X” volume for the week and constantly have to remind male athletes, “YES, I realize you can do that amount for more than three reps and it feels a little light. Just trust me!” and then when you look again, they are on rep six! It drives me nuts, to say the least.

The female athletes that I see generally are more of a “pack” and less of an individual. Often, they’d rather all do the same reps and sets within a group that changes each time through. While this “pack” thinking can also be frustrating, once we get them to understand the reasoning, we see almost no individual insubordination.

Programming Differences and Similarities

While many common weaknesses and dysfunctions are found within both males and females, there are very specific areas that I have observed in our female athletes that demand attention. Two major issues we look to address are knee function and strength and neck/upper back strength. As we all know, knee injuries and concussions are both epidemics. As a result, we pay special attention to those areas within our program. Obviously, there is no such thing as “injury prevention,” but if we can make our athletes even a bit more “bulletproof,” we are doing them a service.

Many of our female athletes come to us in a quad-dominant state. That imbalance in the ratio of quad to hamstring can really be a problem, specifically for the ACL. We also often immediately notice medial knee displacement in young females. As strength coaches, we owe it to our athletes to be able to recognize and program to help reduce these issues.

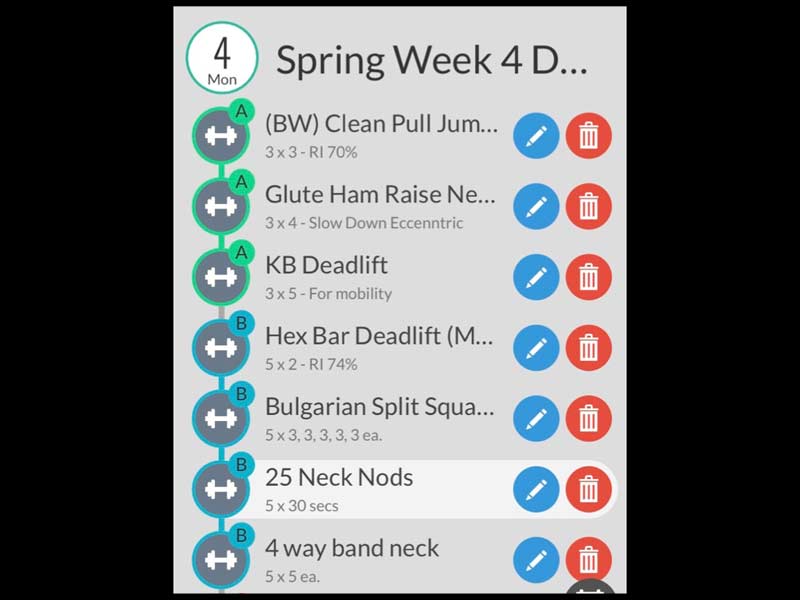

Once we have educated our athletes on these topics, we get to work. We spend a great deal of time on correct jumping and landing techniques: basic jumps, balance and power movements (such as the hop and stop), and correct general movement skills. Tools we use include the mini band (squats and walks to help strengthen abduction and reeducate the body on correct movement), single leg movements (RFE, high box, split variations), and lower posterior chain strength movements such as the Romanian deadlift and variations, Nordic curl progression, and glute ham developer. Our program uses a modified “tier” system with a main movement, an antagonist auxiliary movement, and a mobility movement performed within each set. This gives us ample opportunity to build in these movements without any cost to our strength training sets.

Our second priority area is the neck and upper back. We feel that by strengthening that area, we give our athletes an opportunity to avoid or at least lessen the chance of concussion. While I’ve heard both sides of the debate, we strongly believe that by building the “base” of the neck into a stronger and more stable area, it can withstand more force from a blow and potentially keep the neck from whiplashing the head and causing brain trauma. At the very least, our hope is that a strengthened base will reduce the force of the collision the brain endures.

The second big reason we make this a priority is to allow our female athletes to get into better and stronger positions with higher loads as they progress. From a completely anecdotal observation over the years, I see our females lose position on things such as front squats and trap bar deadlifts long before they are close to a maximum lift. By adding strength to the upper back, we allow those athletes to add weight to the set that is closer in intensity to the 1RM than before.

This is one reason we use what we call a “plate-elevated” trap bar deadlift with our younger athletes. The elevated bar gives them a chance to pull from a position of strength and move to the floor as they progress. We use a wide variety of movements including “scap rows,” upright rows, ring high to low rows, and neck nods, just to name a few.

While it may seem hard to believe for some, an argument can be made to the fact that coaching the female athlete is more challenging than football for a coach with a male athlete background. However, at the same time it can also be argued it’s even more rewarding. While we do make a slight adjustment to our exercise selection, our females basically follow the same blocking and progression/regression protocols as our males. Our females will all squat, bench, trap bar deadlift, and do some level of clean and snatch variations.

I would argue that, in many instances, female athletes accept coaching better than their male counterparts, says @York Strength17. Share on XWhile the style of how you coach females will vary somewhat from males, I can assure you that female athletes accept the same level of coaching as their male counterparts. And, I would argue that females, in many instances, accept coaching better than many males.

Training Female Athletes Is an Opportunity

I would encourage every coach that has not done it yet to pursue any possible opportunity to work with female athletes. Not only will it make you a more well-rounded coach, it is enjoyable and extremely refreshing to work with a population that often has a great attention to detail and very little “ego.” Obviously, there are exceptions and I’m talking in generalizations, but coaching the female athlete is truly a unique blessing to experience.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

[mashshare]