Here in the United States, as soon as our babies are born, we pattern them for football, for basketball, for baseball, and for other multi-player team sports. Racks of baby clothes are filled with cute little onesies with big, bright lettering: “First Round Draft Pick,” “Mommy’s Favorite Shortstop,” and “Daddy’s Little Point Guard.”

What do we never see in those same racks? “I Only Run In Lane 4,” “Future Olympian,” or “I Can Throw More Than Tantrums“—all slogans with nods to Track and Field, or “Athletics,” the sport from which all other sports develop. For the throwing events, the lack of exposure for the younger kids—ages 12 and under—is senseless. Had we been as diligent to expose our younger kiddos to these events in the way we do with other sports, not only would we develop younger throwers, we’d develop more, and better, throws coaches.

Your job in rewarding the individual improvement, regardless of size, is so important. It may be the one thing that keeps the kids coming back to practice, says @ThrowSumthin. Share on XFive Important Words: “Every Kid Has a Talent”

What do these “thrower babies” look like? Are they tall or short? Stocky or slim? Fast or not-fast? Note: I don’t particularly like using the word “slow” to describe a kid’s athletic ability because I believe their ultimate speed can be coached. The answers are an emphatic “YES”!

Throwing is for everybody of every size and every athletic ability. Even for kids who are diagnosed with disabilities—if they want to throw and are able to deliver the implement safely, our job is to coach them. If we use the USATF youth age groups, youth athletes are those aged 8 years and under up to age 18. But I got my “Patience of Job” badge from coaching ages 5 to 12. Learning to hold this age group’s attention for more than three minutes is award-worthy. I was forced to give short, digestible instructions, to be repetitive without getting frustrated, to be creative in giving explanations, and to quickly offer high praise for the slightest improvements.

Just a Coach Who Threw a Thing or Two…

Now, I will assume that if you’re reading this article, you have a general idea of the basic mechanics for each throwing event—or, at the very least, you know what the movements look like. And you may have figured that I know at least that much to even write the article in the first place.

But, to remove all assumptions—and to be as brief with my background as possible—I will give you this: I was a decent thrower in high school and college. I didn’t make it to the Olympics (nor did I give it a good try, to be honest…). But, I was blessed with good coaching at every level from people who saw me as more than a measurement. And it was that connection with those coaches that fueled my passion to share the throwing events with any kid who wanted to learn, regardless of their age.

Over the course of my fairly short coaching career (off and on since 1994…), I’ve coached nearly 60 athletes of all levels, from age 5 to post-collegiate. Some of the high school athletes I’ve coached have received scholarships to compete at the collegiate level, and some of the youth athletes have won consecutive national championships in their events. ALL of the kids I’ve coached have experienced an improvement in their events, and sometimes, that’s all they want and all I can ask for.

We won’t go into the specifics for teaching the fundamentals of each throw here, but there is so much quality content from coaching resource websites that it would take a beginner throws coach very little time to become proficient at coaching developmental throwers. What we can do is discuss how I teach the fundamental movements in a manner that is easy to understand, retain, and reproduce.

Safety and Respect for the Events

So, yeah, I tell all my athletes, regardless of age, that every implement in the throws was once a “weapon of war”…and, although there may be some truth to that, me describing it as a weapon and explaining to them how dangerous these “weapons” can be automatically assigns them responsibility in wielding them.

Throwing is for everybody of every size and every athletic ability. Even for kids diagnosed with disabilities—if they want to throw and are able to deliver the implement safely, our job is to coach them, says @ThrowSumthin. Share on XBefore they take one throw, they must understand that these implements are not toys, that there is ONLY ONE SAFE WAY to deliver the implement, and that learning to throw them sets them far apart from those who don’t throw. This classification of being “different” than others often increases their respect of and interest in the throwing events. It’s also a good diagnostic tool to find those who will likely take the training seriously.

Team…With a “Me” In It

Ah, the power of individual sports in a “team” environment—this was what first drew me into the events. You mean I get my OWN turn to show what I can do while everyone else watches (or doesn’t)? There’s no waiting to be put in the game, no worrying about making the travel squad, no issue with not getting the ball?

Instead, everyone gets a turn—at least three, to be exact. And for many, that’s quite empowering, regardless of the distance thrown. Most throwers, I’ve found, have a touch of introversion; so being able to compete as an individual fuels a deeper psychological need.

I was that kid—tall, athletic build, could move very well, but I had zero interest in traditional team sports. Yes, I was pigeonholed into playing center in basketball (which I absolutely despised, by the way…), and it didn’t take me long to find out that I would rather waste away on the couch than play another quarter on the court. It certainly didn’t help that I wasn’t all that good, either.

When parents bring their kids to me and I find that they have athletic backgrounds similar to mine, I know better than most that this initial meeting will set the tone for the trust exchange between this new throwing family and me. I tell them that my only expectations are that they stick with the program, trust the process, and focus on their individual kid’s improvements. To the kids, specifically, my only ask is that they have FUN learning something new.

Four Key Concepts

1. Moving in Different Planes

We run and walk mainly using movements and counter movements that help to propel us forward. And with nearly all sports, the objective in movement is to get from Point A to Point B as fast as possible and in a straight line. Well, throwing (with the exception of javelin, which some would consider a sprint-like event) is unlike any other sport.

Teaching young throwers about separation, body connection, and independent movement as early as possible and in ways they understand and can improve allows them to apply their interpretation of strength quickly and puts their performances on another level. They will surpass their peers and get lots of looks from other youth coaches, because they actually look like they know what they’re doing at an unbelievably young age.

2. Teaching Separation

Separation of the upper body from the lower body in a torqued or twisted position—in which the hips face one direction and the shoulders face the adjacent direction—is only easy for a contortionist. Young kids, however, twist and turn with their fun and silly dances all the time. They don’t have the joint and spine stiffness of us “plus-30” people, so getting them into the correct position is not hard at all. It just takes repetition.

Here’s how I teach it: I’ll ask a kid to stand with their arms stretched out to their sides as if they’re in the shape of a capital T: a fairly “normal” feeling position. Then I’ll ask them to jump and twist their hips in one direction while their T still faces the original direction. Besides a few cases of severe giggles, this move should cause no pain but will give them a sense of “stretch and twist” in their torsos. We’re not looking for perfection, we just want them to feel it…

3. Body Connection

What we do know is, no matter how hard a kid twists their hips away from the direction of the capital T, none of them will totally detach at the torso and have their legs run down the street and away from their bodies (fingers crossed). The point is to teach them that although their shoulders are twisted away from their hips, their bodies are still connected.

So, in that same twisted capital T, I have them bring the T around to meet the hips. They go from twisted to “normal.” And, congratulations by the way… you’ve just taught your athletes how to lead with the lower body.

4. Moving Parts Independently

Can you rub your belly and pat your head at the same time? You’d be surprised how many adults can’t come close to an acceptable presentation of this drill, but it’s one of the best activities to do to get kids’ brains processing independent movements. And now that you’ve taught the athlete to lead with the lower body by twisting the hips away from the capital T, teaching the independence of the hips for a longer position should be fairly easy.

Rubbing your belly and patting your head at the same time is one of the best activities to get kids’ brains processing independent movements, says @ThrowSumthin. Share on XI teach this by having the kids twist their hips from capital T and stay twisted as their hips move and their upper bodies stay “still.” What will they do? Twirl in a circle with their hips in one plane and their shoulders hopefully in another. The lesson here is: throwing doesn’t have to look normal to be done correctly.

So…Can We Throw Something Now?

YES! After teaching proper positioning and safe delivery, it’s time to put all these new understandings of movement to use.

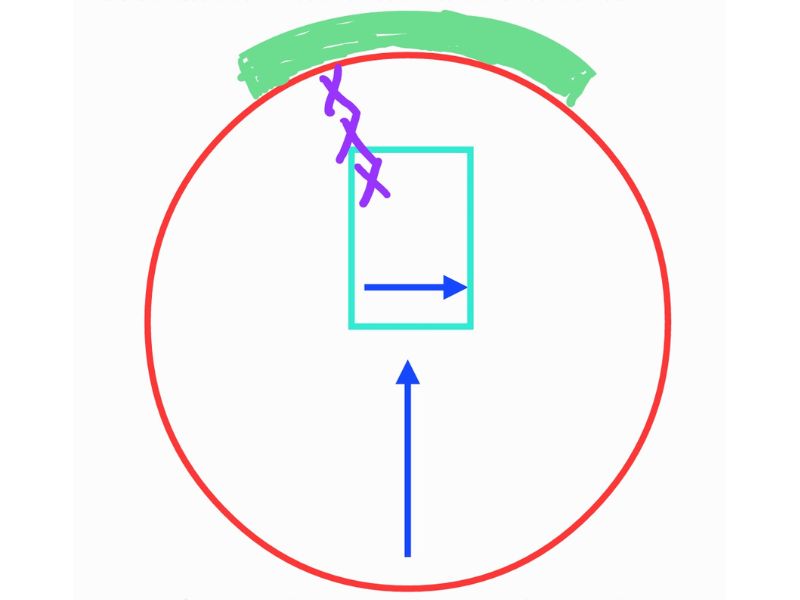

Everything we’ve talked about with those three key movements can be turned into a drill, particularly for shot, discus, and javelin. Start with a capital T position facing the back of the ring, have the kids secure the respective implements in their hands, and twist their hips toward 9 o’clock (for the right-handed shot or discus thrower) and keep pushing with the hips until the shoulders “see” the sector.

Guess what?

You’ve just taught a variation of the standing throw! But! There’s one very important reaction that you must teach against when they start to throw… You have to convince them that they DO NOT need to watch the implement leave their hands. If you initially fail at this (and you will definitely fail), rest assured that resisting the urge to watch the implement land is one of the most difficult concepts to learn—even some Olympians still struggle with it after years and years of training against it.

Instant Gratification, Immediate Feedback: Giving Simple Cues and Measuring Little Movements

The throwing events have so many technical components. Unlike most events in Track and Field, there’s a whole bunch of behind-the-scenes science and math that makes the implements fly far. From the shape of the implements in relation to their flight, to whether the movement from A to B is rotational or linear, getting into the technical pieces of what creates a big throw is usually way more than most kids—and even some older elite athletes—have the attention span to hear.

Being able to take a complex concept and make it understandable for the youth athlete is an art form. Use code words for each movement and repeat those words during drills so that the kids associate the movements with the words—almost to the point that if they hear a word in a non-throwing environment, they think about throws, even if only for a split second. Some of my favorites are “eyes to the sky” and “head up, chest up”—both cues that prompt the kids to create height in their release with their chest and shoulders instead of raising their arms. The neat thing about giving simple cues is that you can absolutely make them your own. Ask the kids what you should name certain movements and have them repeat them as they perform certain drills.

Before they take one throw, they must understand that these implements are not toys, that there is ONLY ONE SAFE WAY to deliver the implement, and that learning to throw them sets them far apart from those who don't throw, says… Share on XOftentimes, the smallest movements can have the biggest impact; so, what seems to the young thrower like an unnoticeable change has the potential to put them in a better position to deliver the implement. Give them one cue and see how they interpret it. If necessary, break the one cue into smaller cues. Sometimes, I use rhythm as a cue for how fast I want a kid to move through the ring. Are they able to complete the movement based on the cue? How many times can they complete the movement correctly in a row? That’s a measurement. When they’re performing drills, tell them that you want as many perfect (uniquely for them) attempts as possible.

We’re not looking for the full throw right now. We’re looking for success in all the puzzle pieces needed to make the full throw. And when those small movements are recognized and demonstrated with quality over and over again, the bigger picture—understanding the full throw—becomes clearer.

Turning on the Power in the Right Place and at the Right Time

After the kids have become familiar with the four key elements, it’s time to teach them how to apply their interpretation of strength and power. Now, some may say I have it backwards—I should teach how to apply power first and then teach the position. This can’t be farther from the truth when teaching youth athletes. I often ask my kids: if the fastest person in the world ran 100 meters in 8 seconds but in the opposite direction of the rest of the competitors, would they win the race? The answer is NO! So, the same thing applies to the throws. Force applied in the wrong direction at the wrong time yields a sub-optimal throw. No matter how strong they are, they must understand how to be patient in turning muscle groups on and off.

Everyone thinks of the throwing events as arm dominant. Well, if you attempt to “arm” any of the throws, you’ll find yourself making an appointment with the orthopedist. There is no way the human body can “yeet” a 16-pound shot 74 feet using just the arm. Each throw is a full body movement that starts from the ground up. So, the force needed to push the implement far into the sector all comes from what force the athlete applies into the ground.

The first question I ask is: which one can you do faster?

- Swim 100 meters in a pool.

Or,

- Run 100 meters on a track.

And, of course, the answer is 100 meters on a track. Why? Because we can apply force forward against an immovable, resistant object (the ground) and it will propel us faster than pushing against a movable, less resistant object (water). The more they push against the ground, the better the throw. We push against the ground using our feet.

Young kids don't have joint and spine stiffness like plus-30 people, so getting them into the correct position isn’t hard at all. It just takes repetition, says @ThrowSumthin. Share on XSo, back to the twisted capital T… with implement in hand, push and turn the feet against the ground with as much force as possible to use the biggest muscles of the body to produce power in the throw. Be patient with the upper body and keep the twisted capital T position as long as possible, but do not engage the arm to deliver the implement until the last minute. Again, we’re teaching how to apply force to generate power in sequence (lower body to upper body) and with the correct timing (when the hips, then the shoulders, “see” the sector). Don’t be surprised if the kids hook the implements either wide left (right-handers) or wide right (left-handers), it will take them a minute to figure out the timing. Just make sure you are throwing in a proper cage with the other kids standing behind and in a distance that keeps them safe. In fact, this is the most important piece of coaching throws.

“Put Your Feet Here”: Using Position Maps

Ladies and gentlemen, I’d like to introduce you to sidewalk chalk—fun colors, cheap and easy to find, and can turn any ring (especially outdoor rings) into an art masterpiece. You know where to hang it…

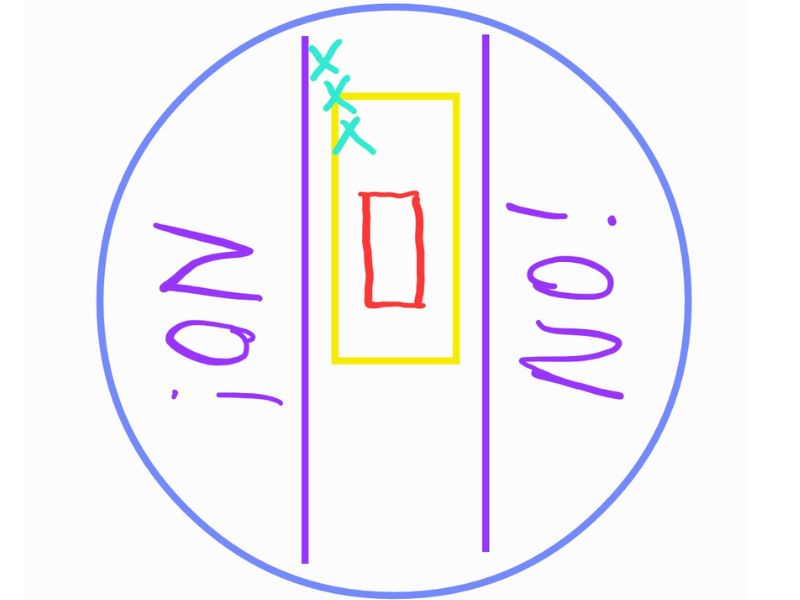

Most kids are visual learners. So, using words to tell a kid which muscles will be engaged when they are in a certain position isn’t nearly as effective as drawing a diagram that shows where they should be. Here are a few examples of my shot and discus ring maps for feet placement. Of course, I make adjustments for the left-handed throwers because their positions will be mirrored of those right-handers (but then there’s the ambidextrous kid who just loves to confuse the heck out of everybody and throws with one hand one attempt and the other hand the next… insert facepalm emoji).

As long as you show them where to place their feet, they can get there with little difficulty. Will they watch their feet to make sure they land on the “maps” you’ve made in the ring? Absolutely! Do we expect that they’ll continue to watch their feet as they progress? Not quite.

The point in drawing position maps is the same as using a map application to find your way to the nearest grocery store. If it’s your first few visits (first time completing the movement), you’ll have to pull out your map app for directions. But after you’ve driven to that same store hundreds of times, you could likely drive there with little thought and with your eyes closed (please don’t do that…). Repetition with positioning creates muscle memory. And applying force to produce power in the right direction at the right time creates good motor patterns.

Every Improvement Is Rewardable

Now that you understand the key points and concepts to teaching throwing basics and fundamentals to the youth athlete, put all the puzzle pieces together and watch for the improvements. Will they produce big distances? Well, let’s define “big.” If a kid who’s never thrown shot before throws 12 feet on their first attempt, that’s a “big” distance for them. And it should be celebrated as such. If another kid throws a centimeter farther than their last attempt, that’s a “big” distance for them—maybe not their personal record, but a better attempt in that series. And that should be celebrated, too.

Drawing position maps is like using a map app to find your way to a grocery store. After you’ve driven to the store hundreds of times, you can drive there with little thought, says @ThrowSumthin. Share on XOne of the concepts I love most about throwing events is that there is absolutely no question when the implement lands farther than it did before. And the results are immediately evident. But the same goes for improving smaller movements through the ring that were once difficult to achieve. The kid who finally hits a proper power position without having to look at her feet—that is an improvement! The kid who trusts that he will hit the correct timing in their throw and resists the urge to watch the implement land—that, too, is an improvement! And even with those corrections to small moves, an athlete can experience an improvement in her throw from that position.

Last I checked, 100 pennies equals one dollar. Every cent (in this case, small movement) adds up to something big. Remember, giving high praise for the slightest individual improvements is paramount to keeping the kids’ interest in these events.

Final Takeaways

Learning a new competitive sport is only fun when there’s someone to compete against. Well, all athletes will inherently compete against each other. But, we have to be diligent in reminding our kids who their actual competitors are—each kid’s competitor is the person looking back in their mirror. Because we understand that every kid has a talent, we have to train them to focus on their individual achievements—and to accept the challenge of others only as a challenge for self-improvement. There will always be someone who throws farther. Question is, can we beat our best at each attempt? Or better yet, can we be consistent at throwing good distances on each attempt? This is why your job in rewarding the individual improvement, regardless of size, is so important. It may be the one thing that keeps the kids coming back to practice.

One of the concepts I love most about throwing events is that there is absolutely no question when the implement lands farther than it did before. And the results are immediately evident, says @ThrowSumthin. Share on XWe didn’t get into the weeds of each specific event because that is not the point of this article. My purpose here is only to explain how I engage youth throwers and how I convince them, through sound coaching and training, that they can be better than they were when they first started. But, their improvement over time depends heavily on you, as their coach, providing a solid foundation in understanding how to move in a sport that looks very little like any other sport they’ve performed.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF