In my experience, coaches either absolutely love medicine ball training or completely despise it (or, as a rare third option, simply don’t know or care that much about it).

I’ll be the first to admit that there are 4-5 times as many useless medicine ball exercises out there as there are actual useful exercises.

Medicine ball Russian twists? Toss those in the trash.

Chin-ups while holding a ball between your feet? Garbage.

Plyo push-ups with your hands on a med ball? I’m actually embarrassed these even exist.

Though there are poor applications for medicine balls, I’m a huge fan of them as a training tool. A tool is really only as good as its application, after all. There are plenty of instances where a medicine ball may be the right, or wrong, tool. It’s simply up to the coach to make those calls with the athlete’s best interest in mind.

A Bit of Background

In November 2020, we moved our facility, PACE Fitness Academy, from a 3,200-square-foot building to a 65,000-square-foot building, joining together with another sports performance team and a physical therapy clinic to build a full-service, performance mecca. Together our trio, PACE, Pro X & Team Rehabilitation, operates as one synergistic unit now under the blended Pro X PACE brand.

That alone could be an article in itself, as I’ve learned so many things throughout the process. One element that stood out, however, was just how much medicine ball training we had missed out on with our old, paper-thin walls and 18-foot roof.

Our new partners, Pro X, have carved out a solid niche in the baseball community, and from their youth programming all the way up to the big leaguers, I watched how masterful baseball players are when it comes to medicine ball training.

On the flip side, I’ve carved out a strong niche in the basketball community—in this realm, medicine balls are not a tool that’s part of the culture the way they are in baseball or golf. Unfortunately, what we do see is a lot of sport-mimicking movements with medicine balls, which just doesn’t cut it.

In the past, I’ve used medicine balls where I could, but not to a great extent; after all, when your ceiling is only 18-feet high, it limits all indoor overhead throwing for most athletes. If you’re familiar with Indiana weather, you know that training outdoors is only a real option for about half of the year, and that’s if Mother Nature is in a good mood.

These… can be specifically beneficial to hoopers due to the unique customization of force vectors, intent goals, and body angles you can use with medicine balls, says @JustinOchoa317. Share on XWhile many basketball players may have been exposed to slams, chest passes, and occasional speed, agility, and quickness (SAQ) work, the exercises I’ll share in this article can be specifically beneficial to hoopers due to the unique customization of force vectors, intent goals, and body angles you can use with medicine balls.

The Downside of Medicine Ball Training

Like anything, there are pros and cons to med ball training, and on paper the cons look like they should outweigh the pros. One big question floating around the strength and performance industry is does medicine ball training really work?

I guess the answer is, define “work.”

For example, one major downfall is that most med ball training is not highly trackable. Unlike barbell training, we can’t quantify every little detail of a medicine ball exercise. The throw or slam speeds aren’t typically measured. The height or length of throws isn’t typically measured. Yes, there are ways to do these things, but usually we don’t. It’s just a really tough thing to track accurately.

Some coaches also say that it’s really difficult to get a true overload with medicine balls. For advanced athletes, medicine balls aren’t heavy enough for power or strength adaptation, in theory. But they aren’t light enough to move with velocities that elicit long-term neurological adaptation, in theory.

So far, this sounds like a dud of a training method. What a waste of time, right?

But then you see it in action, and the value is undeniable. Though there are research papers that support med ball training and research papers that don’t, it all comes down to context. We can’t rely strictly on research for everything we do as coaches—there is some level of instinct to this game. What I see with my own two eyes, in action, every day, tells me medicine ball training is 100% legit.

The Upside of Medicine Ball Training

As far as the pros go, I guess I could just add my two cents and rebut the cons above.

Most of all, I think medicine balls are an outstanding cueing tool: something physically tangible, connected to the body, providing constraint or feedback to the drill/athlete. This is huge. Whether you can track velocity, power, overload, or any of the so-called “cons” of medicine ball training, if you can help an athlete move more efficiently, that is a big win.

I think medicine balls are an outstanding cueing tool: something physically tangible, connected to the body, providing constraint or feedback to the drill/athlete, says @JustinOchoa317. Share on XAdditionally, I still do consider speed, power, and potentiation to be a key benefit of medicine ball training. For example, as a gross oversimplification of power production, we need two components:

- Force (load or strength).

- Velocity (move the load fast).

Medicine balls allow us to take jumps and throws that athletes typically perform with a much lighter load, or just body weight, and add a small amount of load to the force end of that equation to generate more power.

Something like a trap bar jump, which I love, is a great tool to use for very heavy loading. Something like a dumbbell jump could be useful for lighter loaded jumps. But both of these options take away one key component of a jump—the arms.

Incorporating medicine balls seems to exaggerate the arm swing in many cases, which makes it in a league of its own for heavier loaded jumps. Both arms-fixed and arms-free loaded jumps are amazing, and they can be used together.

Basketball players tend to get hundreds of game speed jumps per week. Game speed. The fastest and highest intent possible, which can never be replicated in a training session. That should drive adaptation to some extent.

If it doesn’t, and you determine that an athlete needs to improve their power output to improve those jumps, a medicine ball could provide that overload. Not only globally, but in specific postures or projection angles that the coach chooses. If the athlete’s most intense efforts in games and practices aren’t leading to these gains, implementing 2- to 8-kilogram medicine ball throws, jumps, slams, etc. is definitely a way to increase the force end of that power equation. This can help athletes bust through that performance plateau.

Another example of power comes from looking not just at force production, but at the rate at which that force is produced. Some athletes are very elastic and springy, while others are very muscle driven. Muscle-driven force producers typically have a slower rate of force development.

Using medicine balls to drive maximal intent and velocities in certain movements can expose these slow-twitch athletes to the higher rates of force development needed to break through their speed or power ceiling.

Using medicine balls to drive maximal intent & velocities in certain movements can expose slow-twitch athletes to the higher RFD needed to break through their speed or power ceiling. Share on XEven if the initial changes are acute, over time with consistency and intent, they can be changes that “stick.” Medicine balls are incredible bridge tools, meaning they bridge gaps in our training. They can enhance not only our other exercise selections, but the performance and execution of those exercise selections.

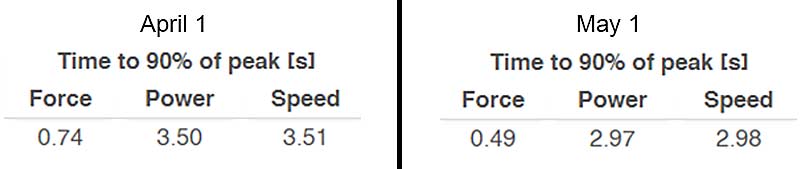

The figure above shows the time (seconds) it took the player to reach 90% of peak force, power, and speed in a 20-meter sprint against 2.5% of his body weight in resistance. Not only are his outputs greater, but he reached those outputs in a shorter amount of time. I can anecdotally say that medicine ball training was a large factor in these changes.

Lastly, medicine balls are extremely versatile. They can be vector specific. They can be multiplanar. They can be skill specific. They can be load specific. They can be completely general. They are durable and moderately cost-efficient. They have a very low level of entry and easy learning curve. And they have stood the test of time. This isn’t always a good thing… but in this case, it is. Coaches are smart, and bad tools eventually fade. Medicine balls are, literally, ancient.

How We Incorporate Medicine Balls for Hoopers

The four main qualities we utilize medicine balls to train are mobility, power, SAQ, and conditioning. Below are some of my go-to exercises and why each one is a powerful tool for driving performance improvements in basketball players.

1. Mobility

Video 1. Hip IR slides are a simple drill you can incorporate into an athlete’s warm-up or as a daily mobility task.

Hip internal rotation (IR) plays a major role in the gait cycle, as well as two-foot jumping. Some of the best jumpers and sprinters in the world have tons of hip internal rotation during their takeoff and acceleration phases, respectively. Should we always mimic the top 1% of the 1%? Not always, but success leaves clues.

On the other hand, not all athletes have that natural ability to internally rotate. There are about three times as many hip external rotators as internal rotators, and they’re all mostly larger muscles and more overused muscles. Sometimes an athlete can get stuck in external rotation and use compensation patterns to navigate around their lack of hip IR. This is just an accumulation drill to expose them to some active hip IR and hopefully restore some of that function.

Video 2. Other than hip internal rotation, T-spine extension and rotation is another highly vital mobility attribute for basketball players to address. Not only is it a functional movement for the sport—think one-hand, cockback dunks—it’s also something that basketball players lack in terms of posture.

With long limbs and tall, slender frames, basketball athletes can develop forward head postures, anterior rolling of the shoulders, and just generally “round backs” over time. Some simple thoracic spine work may help free up some range of motion up or down the chain. I’ve seen this lead to better movement as well as mitigation and/or management of pain.

2. Power and Speed

This is the bread and butter of med ball training. Since the balls come in various weights, shapes, and sizes and can be thrown, slammed, or jumped with at various projection angles and velocities, this is a perfect tool for developing power, speed, and agility for basketball.

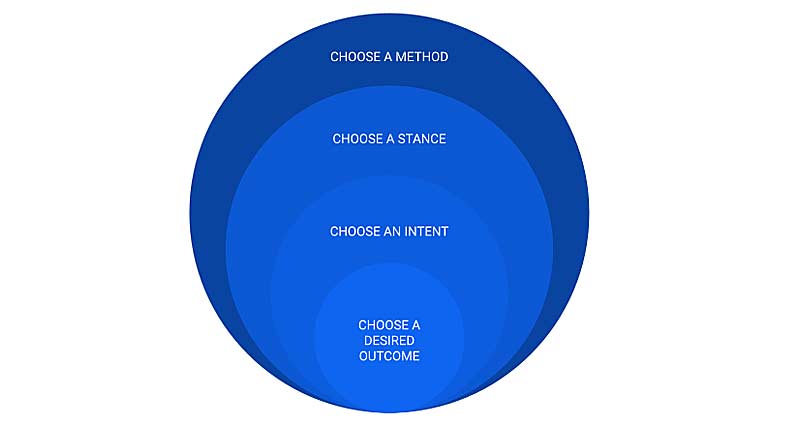

The lens I view this through revolves around three themes:

- Intent.

- Angle.

- Stance.

What is the intent of the drill? What do you hope to see the athlete achieve with the drill? What is the most important part of the drill?

The methods we use to get there are jumps, throws, slams, and catch and react actions. With the intent in mind, what is the best action to get the athlete to meet that goal? What projection angle of the ball works best with the intent in mind? What projection angle of the athlete’s body works best with the intent in mind? What will the athlete achieve by reaching these desired coordination and angular goals?

The stances we use are standing on one or two legs, staggered or split stance, tall-kneeling, half-kneeling, or supine. What stance connects the dots best with the given intent and angles selected for the drill? What stance can the athlete use free of compensation? What stance best lends itself to the action that the athletes will display?

Any of these methods, stances, and training goals can be combined as well. It’s all context dependent.

Using a medicine ball is not a mindless task. To get the absolute most out of medicine ball work, I think focusing on those themes and methods will help point you in the right direction. Below are some of my favorite variations targeting vertical, horizontal, and multi-planar power production.

Vertical Power Production – Overhead Throw Series

These are also jumps disguised as throws. The beautiful thing about this overhead throw series is that—similar to the physics of a box jump—you get maximal concentric intent on the throw/jump while minimizing the eccentric (or landing) loads on the joints.

Video 3. Bilateral: Static-start overhead throw.

Video 4. Unilateral: Single-leg overhead throw.

Video 5. Two-foot gather throw.

Working from most general to most specific, these are great options to add to increase any athlete’s raw power in a vertical vector. The violent triple extension, the maximal intent, the gamification of trying to touch the ceiling—it all transfers nicely to jump performance.

Video 6. Kneeling split stance static start overhead throw.

Video 7. Static start, single-leg overhead throw.

Both dynamic and static split stance throws are great “tweener” variations that aren’t really single leg or completely bilateral. The benefit of the split stance is that you have the freedom to go from a dynamic stance or a static stance. A dynamic stance will allow the athlete to utilize more of the stretch-shortening cycle (SSC), gain momentum during the eccentric phase, and rebound out to create power. The static kneeling stance will remove that from the drill, and the athlete will be forced to create power with no countermovement.

Speaking of the stretch-shortening cycle, if you want to utilize any of the above exercises in a reactive manner to challenge the SSC, you can perform them from a depth drop. Then, these overhead throws put more of the focus on rate of force development, creating peak power faster, and improving reactive strength.

Athletes who are very muscle-driven (or slow-twitch) may benefit more from these reactive variations because they lack the ability to generate their power quickly.

Video 8. This is great example of transfer, where an athlete’s reactive strength index (RSI)—or maximal flight time with minimal ground contact time—went from a 1.89 to a 2.45 on the Just Jump mat after a training cycle incorporating SSC-based med ball drills before each heavy lifting session.

Horizontal Power Production – Broad Jump and Chest Pass Series

These are jump and throw combinations that target an athlete’s horizontal power production. They can be completely customized based on the goal and level of the athlete by mixing and matching combinations of bilateral, unilateral, single response, or multi-response.

There are also coordination demands at play during these variations, as it requires a little bit more self-organization to land from a horizontal jump than a vertical jump since the body is actually displaced from the original takeoff space. The variations we use here are bilateral, multi-response bilateral, unilateral, and multi-response bi/unilateral.

Video 9. Unilateral variation: single-leg broad jump throw.

Video 10. Med ball throw to multi-response broad jump.

The classic chest pass series focuses mostly on upper body performance, although you can turn it into a full-body movement. These are great for targeting power through the torso and arms—again, you can choose the focus based on what the athlete needs by making it reactive (elastic), reset reps (muscle-driven), or supine (strictly upper body). I really like to use these as contrast exercises following heavy upper body lifts.

Video 11. Reactive variation: Standing med ball wall chest pass.

Multi-Planar Power Production

Medicine balls are a staple in rotational sports like hockey, baseball, softball, golf, and lacrosse. They’re also a key focal point in training with overhead athletes, which again covers baseball and softball along with volleyball.

What blows my mind is that nobody considers basketball players to be rotational or overhead athletes when the sport demands so much of both of those qualities.

What blows my mind is that nobody considers basketball players to be rotational or overhead athletes when the sport demands so much of both of these qualities, says @JustinOchoa317. Share on XIn this case, the benefits of these multi-planar medicine ball drills are just as relevant to the game of basketball as they are to any other more traditional overhead or rotational sports. We want to see weight transfer, balance, coordination, and rotational or lateral power. The footwork may be different, but the actions are all alike.

Video 12. Rotational wall throw from a scoop.

Video 13. Figure 8 rotational scoop throw.

Video 14. Med ball reactive bounds (as part of a lateral series including standard bounds).

3. Speed and Agility

Medicine balls are also fantastic speed and agility tools, but not necessarily for the same reasons they’re used for power training. That’s not to say that all of these qualities don’t cyclically enhance each other, but it’s just not the same focal point.

In power training, the ball is the loaded implement moved at high speeds to generate that power. In speed and agility training, I believe the best use of medicine balls is as a coaching tool—meaning it serves as feedback, aid, or a constraint to make the drill work in a certain way.

Video 15. Acceleration throws are a classic drill that every coach has probably utilized at some point. I love these for basketball players because the sport is such a short distance game that it’s very acceleration/deceleration dependent.

By adding some load to an acceleration—getting great momentum and force production going—you can enhance those takeoff qualities as well as challenge “the breaks” by adding a controlled deceleration to end the drill. This can come at a distance, a reaction to a command, or even a reaction to another person in the drill.

Hip Turn Series

This series focuses on utilizing hip and torso dissociation to create levers and positions out of which athletes can maximize their movements.

First, the hip turns get the athlete used to swiveling at the hips while the ball stays in front of their torso. Second, the hip shift turns into a plyo step, projecting them into whatever direction they choose with the ball adding an element of momentum as they transfer it from extended arms back to the hip. Last, the hip turn to shuffle marries the two first drills together for a more functional outcome.

Video 16. In the hip turn to shuffle drill, the athlete drops the ball: This is the “start gun” telling them to begin that phase of the drill. We challenge the athlete to get into their plyo step and first shuffle before the ball hits the ground.

The hip turn series does a great job at repatterning lateral change of direction, getting athletes to flip the hips and create momentum from the ground up rather than pivoting and putting themselves at a disadvantage.

4. Conditioning

Last but not least, an overlooked benefit of medicine balls is their value as a conditioning tool. I am a big fan of the HICT training (high-intensity continuous training) popularized by Joel Jamieson, which is the perfect conditioning for basketball players.

Building a robust aerobic system is vital for athletes, supporting the systems that improve performance—lactic and alactic—while also helping the athlete keep their overall health in check. The issue is that most aerobic training (like jogging, for example) is terrible for athletic performance.

So, what do you do? HICT.

This develops aerobic capacity of the fast twitch muscle fibers, rather than the slow twitch fibers. By utilizing these methods, athletes can improve ATP production, access explosive bursts for longer periods of time without fatigue, and maintain performance levels while still building up their aerobic base.

HICT is performed for durations of 8-20 minutes, with continuous and consistently high-intent reps every 2-3 seconds of the chosen exercise. I love to use very simple and easy-to-learn medicine ball exercises for HICT so there is not a chance of the athlete butchering an exercise for 8-20 minutes straight. Any movement featured thus far, or anything they’ve mastered, will serve them nicely in this case. Of course, actually playing basketball is an irreplaceable conditioning tool for basketball players, but this is just a helpful way to build up a foundation.

Selecting the Right Ball

Giving exercise variations and rationale to thousands of strangers is one thing, but me trying to give concrete answers on how you should program them in your own world would be negligent and flat-out arrogant of me. I don’t know your athletes or your coaching situation better than you.

What I can offer is some practical programming uses that have led to success for our athletes. This is far from a one-size-fits-all system, but it will at least help put some puzzle pieces together in terms of how to use some of these concepts.

First, let’s start with medicine ball choices. My favorite three options are:

- Synthetic leather medicine ball.

- Heavy-duty rubber medicine ball.

- No-bounce medicine ball.

There are literally dozens of other types of balls out there, but these three are the best choices for most anything you could possibly need medicine balls for.

Synthetic Leather

Synthetic leather balls include brands like Dynamax and Rogue. These are 14-inch diameter balls that are extremely durable and versatile. You can accomplish every exercise I’ve discussed here with this type of ball. Although I like some smaller diameter balls for certain exercises, the 14-inch ball can still get the job done.

These balls are rugged and strong enough to throw and slam forever, but soft enough to be the safest option of any ball out there.

Heavy-Duty Rubber

Heavy-duty rubber balls are smaller in diameter, usually between 9 and 11 inches, and are exponentially easier to access when shopping for balls. Rubber balls also tend to come in more increments than other options, with extremely light and heavy options that are easy to find.

Unlike the synthetic leather balls, these balls are much harder to handle. They have a harder surface so aren’t as comfortable to catch. Also, while synthetic leather balls can be thrown against walls or the floor and bounce back at a manageable speed, heavy-duty rubber balls often fire back to the athlete too fast, which could be a health and safety concern. I’ve seen athletes pop themselves in the face by underestimating the bounce-back speed of rubber medicine balls, or simply not know the difference.

I would highly recommend using synthetic leather balls for anything that would cause the ball to come back toward the athlete, such as a wall throw, says @JustinOchoa317. Share on XAny of the exercises discussed today could be executed with rubber balls, but I would highly recommend using synthetic leather balls for anything that would cause the ball to come back toward the athlete, such as a wall throw.

No-Bounce

Lastly, “no-bounce” balls—or dead balls—are a unique kind of rubber ball that have absolutely zero bounce back. The internal makeup of the ball is iron sand, which allows the ball to be weighted down in any situation. These balls come in 9- to 11-inch diameters and various weight increments as well.

A disadvantage of these balls is that the iron sand inside feels “loose” and athletes can feel the weight shifting around within the ball. Sometimes this can alter slam or throwing speed because of the awkward feeling of the ball in the athlete’s hands. Also, wherever the ball goes, it stays. So, if they’re standing 7 feet away from a wall and throwing the ball against it, the athlete will have to go pick it up and reset their position between every single rep. On the flip side, if you throw it straight up or down, it may decrease the amount of time between reps since it should land in the same vicinity it was launched from.

These three types of balls will be able to serve your athletes in any way you need. It’s nice to have all three types around, but any combination of weights and types is still a great scenario to get work done.

Choosing the Right Weight

I welcome any and all weights of medicine balls. I don’t think there is a non-negotiable limit that is too heavy or too light. I’ve had athletes use 2 pounds and I’ve had athletes use 30 pounds. Selecting a weight for the athlete comes back to intent. In general, this is a template that has worked for us when choosing a weight to begin a new drill with:

- For vertical power exercises: Medicine balls equal to 1-5% of the athlete’s body weight are a great place to start. More-advanced athletes can start closer to that 5% mark, while less-experienced athletes can start closer to 1%. This ensures that the overhead throw or jump will remain at high speeds with a moderate amount of relative load. It’s just a starting point, as a coach you can adjust as you see fit.

- For horizontal power exercises: The same scale applies, with a few deviations. In chest pass variations, I often like to contrast those exercises after a heavy upper body lift like a bench press. In some cases, I use a percentage of the load on the bar to select the weight of the ball. For supine passes, 1-2% of the bar weight, and for standing passes, 3-5% of the bar weight has been a nice starting point for our athletes.

This helps mitigate doing advanced power training for athletes who don’t need advanced power training. In other words, it might do them more good to just simply gain strength. If your 1RM bench press is 95 pounds, and you’re looking for a 1- or 2-pound medicine ball to throw, there’s your sign.

The other deviation is that I think the jump- and throw-based horizontal exercises are a good time to push it and maybe break some rules. Horizontal exercises come a lot more naturally to athletes than vertical force production options. Athletes will catch on more quickly and likely need to progress in weight faster.

Not to mention, acceleration requires a great deal of horizontal power. Loading up some extra weight on these without an exact percentage behind it is totally fine. It’s probably totally fine for all of these exercises, actually, but you have to pick and choose your knockout punches. This is one of them.

As far as the speed & agility exercises go, I think the best plan of attack is to choose the ball that the athlete can control with vicious intensity without losing the mechanics of the drill. Share on XLastly, as far as the speed and agility exercises go, I think the best plan of attack is to choose the ball that the athlete can control with vicious intensity without losing the mechanics of the drill. Most of the time, medicine balls under 8 pounds should be perfectly fine for all purposes along these lines.

How We Program Medicine Ball Throws

Finally, the million-dollar question: How should I program them?

I think some variation of these exercises should be in an athlete’s program year-round. Everyone has their own systems and programming templates, but I see these fitting the most on a universal level in one of three ways:

- In a warm-up before a lift, game, practice, or speed session.

- As a part of a contrast, complex, or superset scenario.

- Toward the end of a program as a technique refinement or conditioning drill.

None of these are your main lifts. You don’t get to never squat again and just toss medicine balls around. The medicine balls enhance existing lifts and bridge gaps in the training program.

You don’t get to never squat again and just toss medicine balls around. The med balls enhance existing lifts and bridge gaps in the training program, says @JustinOchoa317. Share on XOur programming revolves around speed development. In early phases of training, we focus on acceleration. This training includes longer ground contact times, greater levels of eccentric and isometric strength, longer ranges of motion, and more closed chain drills. This means we tend to use heavier balls and force-dominant throws or slams, and synergize those segments of training.

As we progress the athlete, we focus more on power and speed-strength, turning some of the strength gained in the previous phase into power with higher velocity movements than they’ve been exposed to in training thus far. This includes now shortened ground contact times, shorter ranges of motion, and more reaction-based drills. Our ball training might be lighter and faster with more multi-response and RSI-based exercises.

Lastly, our programming leans toward absolute max velocity in the final phase. In this phase, we see our shortest ground contact times, our highest velocity outputs, our highest RSI outputs, and more partial ranges of motion. We then match our medicine ball training to enhance those traits. In this phase, the ball may be utilized for technique optimization and extremely high velocity slams, throws, or jumps. In a perfect world, we can execute all three phases of training with room for a slight deload or transition phase before going into a team camp, tryout, or season environment.

Medicine balls don’t replace the basketball or barbell—they bridge the gaps between them. For our basketball players, we can cover a multitude of athletic traits, postures, and purposes with a simple and easy-to-use tool. If you have the facility space and available equipment, I would highly suggest making medicine balls a year-round training tool for all the hoopers you train.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF