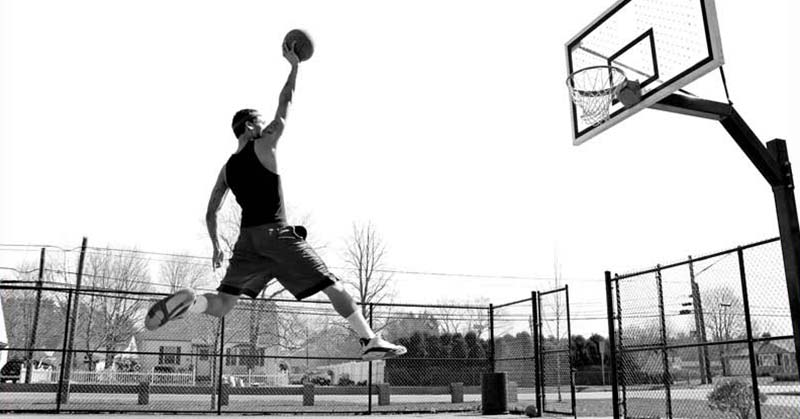

When it comes to validating one’s self as an athlete, jumping is the first request on many training priority lists. Think of the famous sporting feats that are etched in our memory:

- Vince Carter leaping over Frederic Weis in the 2000 Olympics for the thundering slam dunk finish.

- The famous front-flip touchdown by Jerome Simpson of the Bengals.

- Bo Jackson leaping and running up the outfield wall following a running catch against Baltimore.

Sure, it’s embarrassing to get beat down the court or on the open break by an opposing player, but it’s far more humiliating to get dunked on (Weis lost the opportunity to play in the NBA due to his notoriety as the 7 foot guy who got jumped over), your shot blocked, or a spike rammed down your nose. Nobody is “posterized” by simply getting beat by an offensive player downfield. It is as if Stan Lee decided that the superhero version of the modern athlete was one with unbelievable jumping ability. The marketing engine, as it exists, likes to cater towards those athletes with these superhero aspirations. Who wouldn’t want a program that will turn them into the Batman of athletes for only $67?

Speed wins games, but jumping seems to be the envy of those who want to impress. It also doesn’t hurt the cause of becoming a better athlete. Real vertical jump training with the goal of advanced performance can be muddy waters, particularly through the efforts of those who have seized up much of the available information with marketing based information, directed towards novice athletes.

The goal of this article is to provide some philosophies and guidelines for the rest of us, those who are interested in the long-term process of sport mastery, and the journey of taking athletes to their best possible performance. These points are often left up to debate in the various training forums and roundtables of the world on the subject of increasing vertical leap ability so I am sharing my thoughts on them, all in one place, right here. I derived these from my time as an athlete, a track coach, a strength coach, as well as in my work with online clientele of various backgrounds.

Let’s start with a common point that most coaches already know, but one that may need a bit extra clarification in regards to jumping.

Exercises are in your program for a season, and sometimes a lifetime, but are only a means to an end.

I hear it all the time:

“You need to be doing X exercise if you want to jump higher.”

In athletic performance training and particularly vertical jump training, there is a recurring theme of “exercises”. Often athletes swear by this or that exercise, or exercise sequence, in regards to their athletic ability. Track athletes often carry with them an exercise that “they need to be doing” because there was “this one time” in their athletic career when they were performing that particular exercise and competition went well for them.

The truth is that there is a window of time each exercise will be effective in providing a significant short-term boost to vertical jumping ability, largely due to the skill improvement that the particular exercise delivered to the athlete’s jump technique. Once the skill improvement is transferred, there isn’t as great of a need to keep introducing the exercise in such a volume during the rest of the athlete’s career.

For example, as far as speed training is concerned, I have found that the barbell hip thrust is a fantastic way to get an athlete’s glutes up to speed in terms of activation and pelvic posture, but once I have brought an athlete to the appropriate activation level, bringing their max from 500lbs to 550lbs by continual focus on that exercise is probably a waste of time. With the new level of activation gained from hip thrusts, many of the other exercises that they do will help to maintain that improved strength and size of their posterior. It is a similar story with jumping.

The following are some examples of traditional jump exercises, and the corresponding skill of the jump that they can bring up to speed.

- Jumping rope provides a rapid boost in ankle function and stiffness for an athlete who tends to live on their heels.

- Squatting provides a rapid boost in athletes who need to learn to apply forces for longer periods of time to the ground in two leg jumping. (Vertical jump height off of two legs is a stark contrast to one leg as the amount of time that an athlete can input force into the ground directly correlates with the final vertical velocity of the jump).

- Plyometrics provides a rapid boost in performance in athletes who lack stretch shortening cycle efficiency and general foot strength.

- Pistol squats provide a rapid boost in leg stability and linking of the feet and hips.

- Olympic lifting gives an immediate infusion of posture and coordination through triple extension of the hips, knees and ankles.

- And so on and so forth.

These exercises will provide a rapid boost for a period of time, as they but in order to attain long-term progress, many of them will need to take a back seat to what is truly important. Clearly they should be kept in the program in some form, or rotated to prevent a lack of accommodation. Also, we know that a rotation of exercises that are very close to velocity and mechanics to the primary exercise are vital in long-term athletic improvement for motor learning and accommodation reasons, so strategic use of exercises will also rotate based on these needs.

Although many exercises must be kept in a program for the purpose of maintenance in particular qualities, the primary areas that truly need to be addressed for continual jump improvement during all periods of specific and competitive preparation in order of importance are:

- Specific work capacity in the type of jumping that one wishes to improve (the ability to jump maximally and in enough volume to deliver repeated, specific training effects).

- Speed. Specifically, acceleration.

- Rate of force development in the specific motor pathway an athlete utilizes to jump. Quick jumpers prefer specific plyometric based movements, while power jumpers ofen prefer specific barbell oriented movements such as squats or barbell step ups).

Understand the squat to bodyweight debate. Lift for explosiveness and complimentary benefits, not to hit a magic number.

“To die as a warrior means to have crossed swords and either won or lost, with no consideration for winning or losing.” — Miyamoto Musashi

What in the world does the above quote have to do with lifting for athletic performance?

Well, aside from giving me an excuse to put a samurai reference in this article, it also represents a nice ideology for the purpose of strength training as far as increased athleticism is concerned.

Just like the warrior who enters battle for the ritual of combat, and not so much the determined outcome as a means of validation, the athlete who enters strength training does so for the transfer of skills to the field of play, and not the outcome goal of lifting itself.

Why would anyone validate their ability as an athlete based on a means used to train, and not the actual competition itself? This happens regularly with strength. Although barbells are a great and often indispensable training means, when the urge to utilize the barbell as a form of athletic (or personal) validation creeps in, the whole training system can be thrown out of balance.

This mentality can also cut athletes career progressions short as athletes thrown through the barbell grinder in high school or college can often scrape out nice performances for that particular time period, but struggle and regress in the next phase of their athletic journey.

Another thorn of this mentality, particularly with high school athletes, is that those high school athletes who responded well to year-round heavy lifting in high school will mentally rely on this type of work as a means to success in their college years. This often spurs a negative cycle of regression on their part, which the solution to is often, “more heavy lifting!”.

As far as improving athleticism, lifting weights serves the purposes of:

- Improved posture

- Body awareness

- Coordination

- Joint stability

- Potentiation of proximal speed and power training sessions

- Positive hormonal changes (testosterone and growth hormone)

- Increased cross-sectional area of relevant muscle fiber pool (when done correctly, and there is a limit to this based on an athlete’s genetics)

- Increased strength at key joint angles and torques

Looking at these benefits it is easy to see that strength training is an important tool to making the rest of training better; any of the benefits are those that can easily be “maxed out”, early in their use or an athlete’s career. For example, an athlete will reap immediate body awareness, explosive coordination and postural benefit from a well-designed lifting program, but those benefits will only take them so far. There isn’t an infinite improvement rate as far as posture and coordination are concerned.

As far as vertical jumping goes, athletes with a great squat to bodyweight ratio will jump higher than their weaker counterparts, all other factors being the same. There is an important chicken-or-the-egg consideration to make with these athletes, however. Athletes who are naturally strong and explosive will experience a rapid train of improvement in barbell exercises, along with lots of psychological momentum. Athletes on the weaker end will find rapid improvements via lifting, especially in the motor benefit realm, but their results will taper off far sooner than their stronger counterparts. Unfortunately, rather than playing to their more natural plyometric and elastic strengths, these weaker athletes will sometimes put their heads down and strive for a particular lift number that hamstrings (sometimes literally!) their long term athletic progress.

“I was pretty average until I decided to work hard to hit that 2.5x bodyweight squat, after which I won the Olympics,” said no athlete ever.

Athletes who tend to improve their vertical jump the most by focusing primarily on the lifting portion of their program are, more often than not, athletes with a lot of fast twitch muscle mass, who generally jump in a style resembling their lifting. Their lifting makes their jumping better (to a point), and their jumping makes their lifting better. Realize that many athletes are not built like this.

Lift maxes are a trick of sorts. Maximal strength often indicates the functional motor pool available in an associated movement, but intensely pursuing maximal strength doesn’t transfer well to speed based activities. The goal in lifting to bring maxes up that help athleticism is to do so in a way that doesn’t look like you are actually training for it; lots of powerful work in the 60-80% range, coupled with plenty of explosive plyometric, jump and sprint work. Believe it or not, many explosive wired athletes will find that their lift maxes will actually go up by following this methodology over a powerlifting style of training. Bottom line, speed builds useable strength more than strength builds speed.

Use Olympic lifts for skill development and speed, not to end up on AllThingsGym.

As long as we are on the topic of lifting, find me an NCAA strength program that doesn’t use any Olympic lifts. The Olympic lifts can be very effective in the right context for building vertical jump related qualities, but they can also be lousy when they are worked in the wrong direction with the wrong cues, especially in athletes seeking to break through to the higher end of their genetic abilities.

Let’s make this as simple as possible and talk about the benefits of an Olympic lift in regards to vertical jumping skill. Regarding vertical improvement, any lift is only as good as it can improve the skill of a jump in an explosive manner. Here are the positives of Olympic lifting:

- Teaching coordination in triple extension.

- Providing a new set of motor instructions in regards to explosive concentric triple extension.

- Teaching basic force absorption qualities in the catch.

- Teaching advanced force absorption qualities, in transfer to two leg jumping, in the full catch.

- Teaching posture in conjunction with explosive efforts.

An Olympic lift is a “jump”, but with one caveat: there is a bar that manipulates the athletes’ center of gravity (just like any barbell lift). Although a proper Olympic lift is done where the bar never passes more than a couple of inches away from the body, this is often done in-correctly more times than it is done correctly.

Getting into the 1RM race as far as cleans are concerned is also a battle that many athletes will eventually lose when it comes to building a better vertical jump. In order to bring a clean or snatch to its own highest level far past the initial complimentary benefits, the body must adapt itself to a different set of neural instructions that jumping requires, especially in regards to the feet (which we’ll get to in the next point).

Bryan Mann, in his great book, Velocity Based Training, recommends keeping a bar speed of at 1.2-1.4 m/s on cleans with perfect technique, the bar never straying far from the body. Doing heavy and relatively slow cleans with a bad bar path is one of the best ways to keep an athlete below the rest of the crowd, as this type of work has zero, or even a negative transfer to vertical jump height.

Teach the feet.

In nearly every athlete I train who has a lousy standing vertical jump, the primary deficiency isn’t one of power, but rather one of foot function and force transfer through the torso. I have female high jumpers clearing 5’10 who regularly vertical jump under 20” because of ankle function. For high jump, this isn’t hurting them (and I am not on a mission to improve these girls standing jumps), it just reflects itself in the way that they jump off of two feet, as their primary reaction in directing force though the ankle is based around negative shin angles to perpendicular shins, where standing jumps rely more on positive shin angles.

Many athletes who have a well-rounded athletic background have pretty good foot function in regards to jumping. It is often over-specialization, coupled with the over-use of standard barbell training performed on a regular basis that can cause dysfunction in this area. Wearing shoes all the time also tends to put a damper on fast, reactive feet, as the plate of the shoe causes foot neurons that usually fire individually, to all wire together in one brute reaction to the ground.

In athletic performance, the faster an athlete can direct pressure to the big toe, and the more powerful the extension of the plantar flexion, the higher an athlete will jump. When an athlete lowers their frequency of re-enforcing this quality, and starts to spend two or three days a week performing exercises where they focus on directing force away from the big toe, or delaying it until the very last second, such as the way that cleans and snatches are often taught, this can wreak havoc on vertical athletic qualities. I see this all the time when we test the jumps of strong collegiate athletes who have been on a regular lifting program through high school. The ones who display the best vertical jump mechanics in the lower leg are often those who haven’t lifted much in their past, and played a jumping sport in their earlier school years.

So what to do?

The solution here is to make sure that athletes are being cued correctly in lifting activities (not lifting through the heel, and keep plenty of lifts that allow for some extension through the toe at the top of the lift), and perform lifts in a low enough volume as to not interfere with the correct lower leg action. It is also good practice to mix and superset barbell work with exercises and drills that do encourage the correct foot function, such as low-level plyometrics, assisted jumps, and lower leg jump drills. If I have the space, I’ll always superset Olympic lifting sets with a few vertical throws, focusing on complete ankle extension, or low-amplitude speed bounding, depending on the vertical outcome goal.

I’ll also say that many of these exercise prescriptions may be a bit primitive in light of Chris Korfist’s ankle rocker drills, while are one of the best new areas of jump training I have read in a long time, and they can restore foot and ankle function in a hurry.

Know how to do a depth jump correctly and use energy efficiently.

If you look up “depth jump” on YouTube, be prepared for a cluster $%& of the highest magnitude. Depth jumps are rarely taught the way that they should be. I was fortunate to come across a vertical jump program (The Science of Jumping) when I was in high school that revolved almost entirely off of the correct performance of the depth jump exercise and its variations. Here are some common faults in typical YouTube videos on the topic:

- Improper posture during the drop and land phase (often looking down).

- Improper or minimal use of the arms (very small or non-existent arm swing).

- No emphasis on landing softness whatsoever. No emphasis on where the foot pressure should be (the balls of the feet, and possible initial mid-foot pressure for single leg jumpers).

- No emphasis on landing stiffness. Many athletes go into far too much knee flexion upon landing. Since the goal of depth jumps is rate of force development under increased load, knee flexion should be less to allow less ground reaction time.

- No emphasis on the need for maximal upwards explosion on each repetition (this is the number one offense). Depth jumps are maximal efforts. In order to maximize upwards explosion, an outcome goal, such as an overhead target (for force) or a collapsible hurdle (for rate of force development) should be implemented. Athletes should seek to improve these outcomes throughout training sessions.

Let me talk about one aspect of depth jumping, and plyometrics in general, that coaches and athletes need to know: smoothness.

Good jumpers… really good jumpers, have one main thing in common. They make their jumps look incredibly smooth and easy. Good jumpers are quiet. This is something that is easy to say, but rarely put into practice. Check out this force/time graph of a novice jumper vs. an accomplished jumper to see what I’m talking about from a force perspective.

What is the best way to improve one’s ability to produce force efficiently? A plyometric progression, starting with correctly coached drop jumps. Drop jumps (dropping from a box of appropriate height with an emphasis on landing mechanics) is a great way to teach force absorption. Once an athlete knows how to do this right, then to make lasting changes, a somewhat high volume of work is needed to wire it in. This is where submaximal plyometrics, coached with the same cues as the drop jump can help to gear an athlete’s nervous system and muscle-tendon structure towards transferring force in a more efficient manner.

Understand the difference between body types in training.

Not every athlete is destined to squat twice their bodyweight. Not every athlete is born to master a depth jump from a 1 meter platform. Athletes need to eliminate weaknesses that are liabilities to their jump performance, but they shouldn’t pursue their weaknesses past this point to achieve their highest vertical potential.

Ultimately, athletes are built, and subsequently, developed for a particular jumping style. Through their adolescent development, their neurons that fired together to form a particular platform of movement, wired together to make that movement more powerful in their maturity.

Imagine taking a competitive swimmer at age 22, who had no real land based sport background and expecting them to be able to perform a technically perfect triple jump within a few months, or even years! Imagine taking a competitive triple jumper at age 22 and expecting them to perform a perfect butterfly stroke! Once the way our bodies tend to move are “wired in” those sequences generally represent the most powerful way that a person can move and apply force, and future specialization in the body’s current weakness is an impossibility.

When an athlete learns to produce force in a particular manner through adolescence (this is usually done in accordance with the athlete’s individual strengths) these patterns are wired in, and it becomes impossible to wire over it with another pattern that eclipses the old pattern in terms of power and efficiency. Athletes sprint and jump from just a few years old, so these patterns are very hard wired. Granted, there are technical refinements that can and should be made to anyone (otherwise, we might as well give up coaching!), but in general, wired movement patterns are hard to break.

What I am really talking about here is that some athletes will utilize little knee bend and elasticity in jumping (they often make good high jumpers and single leg jumpers), while others use considerable knee bend (they tend to make good 60m dash athletes and football players). You can’t take either of these athletes and expect them to jump like the other. In the same vein, you can’t take one athlete and expect that training like the other is going to bring them to their highest potential.

Don’t stop playing team sports and realize it’s power as a maximal jump incubator.

Within team sport play comes a wealth of explosive movement patterns. The highest levels of explosive power as exhibited in jumping are the product of other more basic movement patterns found in sport, such as the acceleration found in the jump approach, or the rapid decelerations that the lower limbs encounter during the absorption phase of the jump.

Team sport play also helps to maintain elasticity and build stronger lower legs, ankles, and feet. They deliver some of the strength that can be built only through repetition. The constant, rapid fire cuts, accelerations, quick hops and outcome based sport movements (such as jumping for a blocked shot) offer a unique training stimulus that can’t quite be attained via traditional training methods.

Remember, training in many cases is putting together very close variations of the primary movement you are trying to improve. In the scope of jumping, an athlete is getting plenty of jumps, no two of which are exactly the same which builds a bigger “bank” of motor patterns that the body can use to create a stronger movement. The variety also prevents injury, and perhaps of the greatest benefit, utilizes the important principles of fun and competition. Anytime you can make hard, effective work fun, it is generally a win-win.

Although experienced jump athletes who are specializing in something aside from basketball, volleyball or football need a base of team sport play in their younger years, they clearly shouldn’t be playing games constantly in their time of specialized performance. Despite all this, they should never completely lose touch with their team sport roots. Matt Hemingway re-vitalized his high jump career through his love of basketball in his later years of competition. A few 30 to 45 minute sessions of off-season, controlled team sport play for a few sessions a week goes a long, long way in keeping the movement bank of track and field jumpers full for their long competitive seasons. (Side note: hurdling is a great way to keep the movement bank full with slightly less risk of a rolled ankle)

Conclusion

My vertical jump journey, and the way that I coach athletes has been heavily influenced in some way, shape or form by the above principles. Most of them took around a decade for me to truly understand, but now that I do, I am a better coach and mentor for it. Each of these points on their own can be helpful. Together, they can make a great difference in producing the next great aerial touchdown or center-clearing dunk, or at least, the aspiring junior athlete who finally impresses his friends by shoving the round-ball through the rim.

“By changing the way you do routine things, you allow a new person to grow inside you.” — Paulo Coelho

For more information on the vertical jump see Joel Smith’s book “Vertical Foundations”, now available in both print and eBook.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

Hi Joel, nice informative post. Jumping is an integral part of any handball game such as basketball, volleyball, and it is also one of the major requirements for many Olympic sports. A suitable jump training guide will feature exercises that not only would help build our strength but also improve the quickness, a combination of which gives explosive vertical jumping height. Since 2 months ago I have been trying to improve my vertical jump with the help of TrainingMalls’ workout accessories.

stellar article. The first thing that comes up on google for “barefoot vertical.” This article reinvigored my determination to practice olympic lifts, and a good reminder to work on those quiet landings!

Hi Joel,

Great article. I found philosophy #3 pretty interesting since I do depth jumps in my own workouts. I agree with what you said, often they’re done pretty poorly and although the negative effects of improper form might not be immediately visible, when you compound the effects of years, it can really add up.