[mashshare]

Medicine balls. Everyone is familiar with them and loves to incorporate them in some type of way. Whether you slam them, throw them off a wall or in the air, or do some circus trick with them, medicine balls are fairly universally accepted in some manner. Maybe it’s time more people started testing with them as well. They are already a staple in most training programs, so using them to test and assess seems like a natural progression.

Using #medicineballs to test and assess seems like a natural progression from training with them, says @ShaneDavs. Share on XTesting them is a little less straightforward than you may think, however. Of course, you could grab a piece of paper and a tape measure and get some decent objective data, but I think there is a better way. Now, with the help of the Assess2Perform Ballistic Ball, it’s possible, scientifically validated, and, dare I say, easy.

This piece covers the three most common medicine ball tests, a couple variations of each to consider, and how to analyze the performances. If you do not currently have access to a sensor-based MB, you can still take away some practices for standard MB testing.

Why Test with Medicine Balls?

We can gain a lot of information using medicine ball tests. We can see how an athlete responds to a testing environment, how they move in more complex coordinated patterns than simply jumping or squatting, and how they respond to training, all with a fairly safe and practical method. The load is light (ballistic) and the information we gather reinforces our training or helps to make the necessary changes.

Testing isn’t just about measuring. It is a means to accountability, not only for the coach in making sure what they do is actually effective, but also for the athlete. Without numbers, how do we know athlete efforts are as they appear? How do we know that their Wednesday afternoon effort is on par with their ability or peak values?

Testing can give valuable insight into program data or simply incentivize, encourage, and motivate your athletes to “give their best,” so to speak. At Exceed, we’ve tested jumping and sprinting for a long time now, and when our college and professional athletes return after the season they know there will be testing. Now, thanks to the Ballistic Ball, we can add medicine balls to the mix.

The main reason for adding the med ball tests is the simplicity and safety involved, but here are other quick reasons that you’ll love them too.

- Max effort testing can be risky, but it’s much less risky with medicine balls.

- Testing with medicine balls requires very little set-up time.

- Science supports MB throws and they are practical to do in or out of the lab.

- Athletes enjoy throwing medicine balls because it is primitive and engaging.

- Any time you add metrics or tech to a movement, athletes try harder. It’s science.

- MBs bridge the gap between lifting and sport coaches. Testing with a med ball can better display some need for training to the sport coach.

It’s not so much about improving the tests we all love so much. Ask any coach or trainer and they’ll most likely agree that sprint, jump, and lift tests are a standard and effective collaboration. They are pure, direct, specific, and undeniable, but medicine ball testing isn’t about better or worse—it’s about different and more. We can test a sprint as long as the athlete is fresh, injury-free, and motivated, and jumps are a great addition but practically limited to the lower body.

Medicine balls won’t replace your #combine tests, but they are no longer on the ‘B Team’ either, says @ShaneDavs. Share on XOn the contrary, the posterior scoop toss (between the leg overhead throw), for example, coordinates almost every joint at max output. I am absolutely not arguing against using those tests in any way—we do so practically every day in some manner—but adding the medicine ball tests reveals a greater amount of information and touches on some unique patterns and qualities hard to quantify in the traditional tests. Medicine balls are not going to replace your combine tests, but they are no longer on the “B Team.”

Medicine Balls: Is the Science There?

There is enough science and research out there for a coach to do their homework and make some decisions on whether med balls, both as a test and training method, are for them. Exceed’s approach to new tests or technologies is to use them and get a lot of data and familiarity with the data, and then worry about interpreting it when you have enough. Studies are fickle in that often the conclusions differ based on test subjects, methodology, and a number of other factors. Arguably, the best practice is then to test the movements that make sense for your clientele with a premium placed on execution and replicability, and your data will ultimately determine the effectiveness of their use. In my opinion, the med ball tests are much more about long-term development than short-term novelty, so treat your “study” in that manner.

Certain sports are more conducive to medicine balls simply in terms of game-like motion. Including MB work in special-strength phases for throwing or rotational sports (such as baseball, handball, golf, hockey, and the throw events in track and field) would seem obvious enough. But how do the medicine balls fare in sport specificity studies? Findings vary, believe it or not, and although some research states that including medicine ball training in unison with a traditional baseball off-season program would yield an increase in power or velocity, another study on medicine balls in training argues that no velocity improvements were noted on post-intervention testing.

You can probably find research to validate any point if you look closely enough, but the majority of research is in favor of throwing med balls in an attempt to improve velocity. Even beyond baseball studies you can find good cases for including the throws, such as a study on handball athletes who improved throwing velocity by incorporating MBs into their training routine.

Regardless of what sport you train for, testing athletes with medicine balls seems like an appropriate method provided you know the limitations and drawbacks of testing in general, and specifically with medicine balls. Scientifically, a coach would want medicine ball training to improve performance, evaluate talent, and demonstrate reliability when testing. The science is rather specific to what medicine ball testing does well, such as power testing with overhead athletes, and what the complexities (contradicting science) of sports movement can create at times. The science supports testing with medicine balls, but most of the research is on chest throws, while other movements are working their way into more validity.

A coach will have to make the decision to invest in a Ballistic Ball versus testing with a tape measure or radar gun. With research on reliability of testing medicine balls with different weights, we avoid measuring lightweight balls, as of today, and typically use a 10- to 13-pound ball. Lightweight balls are population-specific but the athlete being tested should use an appropriate load. Based on current science, the ball is scientifically validated for testing and adds context to the throws by showing how an athlete generates their power. We still measure for distance, but velocity is a better measure and can be much more “facility friendly.” Find out what works best for you and use additional measurements along with the A2P Ball to ensure redundancy for an auditing system.

The Perfect Testing Protocol

Not to harp on how to avoid testing mistakes, but not having a standard approach to testing makes gathering quality information from your data difficult. In fact, the hardest part about data collection may not be the analysis at all, but the policing of the protocol. Athletes inherently want to win and will do anything to find a loophole or a “rule-bending” way to exploit the technology. If a gap or weakness in the protocol exists, the cunning athlete will find it immediately and take advantage.

You can see a common example of this by watching an athlete cheat a mat-based vertical jump. They swing their legs forward and land in a very deep squat, keeping their feet in the air as long as possible. When the protocol is “Jump up as high as you can,” this seems like a logical way to be in the air as long as possible. By stating rules and criterion more definitively, it helps to eliminate these issues but can drastically alter the cheaters’ jump heights. If the coach/test administrator is not diligent in policing the test, athletes will find a way.

Along the same lines, the testing protocol must have meaning to the athletes and it must be replicable. Be firm in your standards but explain the underlying purpose of the test. When they understand what the test is truly looking to display, many athletes will give a valid effort rather than try to cheat for a higher score. It’s also easy to replicate a test once it has a standardized format and meaning for the athlete. Based on the research on familiarization with medicine balls, some movements may take more than a few reps to be considered valid. So practicing and repeating the efforts stringently will improve the validity and efficacy of the test.

Honest Error Correction

After considering the ways athletes “cheat” the system, let’s look at the common honest mistakes and errors. We find that, as in standard strength training, most errors start at the setup. We all know it would be very difficult to squat your max weight if you started with your feet all out of whack. This is the same for testing protocols, including medicine ball tests. How an athlete is set up at the start will dictate what happens when the movement begins. Instead of waiting for a catastrophe, spend some time and energy creating a repeatable and optimal starting position for the athlete and give them a fighting chance.

Most athletes, if given the right circumstances, will do the best they can and not cheat, as the movements don’t have much room for error. If you spot a strange motion, explain the fault and repeat the test. Sometimes a video camera alone will keep athletes from attempting a conscious mistake, but showing a clip afterward is priceless when errors cannot be rectified by verbal explanation.

Spending the time it takes to refine your testing protocol is worth it, says @ShaneDavs. Share on XFinding your own concrete protocol will take some time but it removes so much of the havoc on test day. Your protocol and verbal cues could simply be camouflage for your cheating prevention or they could ensure a great starting position for replication purposes. Either way, spending the time it takes to refine your protocol is worth it. For a few ideas on procedures, here is a return to play article written about five years ago that shared and outlined some solid points on medicine ball tests.

A Few Points to Consider

After giving some thought to your protocol and to what you are trying to accomplish by testing—and for that matter, training with medicine balls—you should consider a few points. First, medicine ball throws are not specific to sport. They are as specific to pitching, hitting, and throwing as squatting is to jumping. They are tools and can help the general abilities that improve the sport skill.

Take the baseball swing, for example. Part of the setup and movement strategies associated with hitting a baseball involve timing, reading, and decision-making. It is not just output, as the medicine ball throw is; it also involves a significant amount of input and processing. So throwing a medicine ball does not, and arguably should not, mimic your sport skill exactly. It is a general strength or power tool that only helps the output part of the equation.

Similar to the swing is the throw or pitch. Handball and baseball throwing involve accuracy. Now, it’s nice to have a little bit of direction when throwing a med ball, however, the outcome or result doesn’t fully rely on the thrower’s ability to hit a target. A handball study on throwing velocity showed precision was unaffected while power improved. So a non-specific throw can still benefit a sport skill. To me, this means don’t overcoach the MB movement like it’s the sport skill. The repetition and effort that comes with throwing for numbers (testing with the MB) alone will benefit the velocity and power of the sport skill.

Lastly, I encourage you to rely less on normative or comparative data and look more closely at an individual’s progress. Why wouldn’t the normative data be important? Technical differences will play a role in the velocity. A stronger and more powerful athlete might throw a medicine ball farther than a weaker counterpart, but the velocities may not line up. Although my last points were about not worrying about making the med ball throw a sport skill, the mechanics and refinement of the throw can play a role in some of the data you’ll see.

What Is Rotation? What Do You Look for? How Do You Test It Properly?

At times, body rotation is confusing; while most coaches understand that torso rotation would require the hips to remain locked, the end goal is something entirely different. What we want is a rotation of the hips and shoulders, somewhat in unison, to generate as much force, power, and velocity as possible. A factor to take note of is that hip power from the extremities usually transfers through the spine, rather than the spine doing all the work alone. Generating power from the legs and transferring it to the arms (and torso) is typical of almost all sporting movements (regarding rotational power). Although the spine dissipates and recycles energy very well, most of that ability comes from Mother Nature, not being good at core exercises.

Something else to consider is the fine line between seeking out useless spine mobility and moving safely. Obviously, adequate movement is important for joint health, but efforts placed on increasing range of motion of the trunk may not help performance, according to some research. The argument was that a limited range of motion at certain joints can aid in velocity when transferring force from the lower to the upper extremities. Coaches value core training because they want to protect the spine, but they also know that mid-section strength is vital when transferring forces.

Rotational throws tend to be the sloppiest med ball movements, which is risky and hard to test well, says @ShaneDavs. Share on XWhy is this all important? Simple. The value of rotational power needs to be put into a healthy perspective because rotational throws tend to be the sloppiest of the medicine ball movements. They can get ugly and lead to poor control and coordination. Without knowing the true prerequisites of good-looking rotation, or at least what you’re actually testing, there tends to be a slippery slope of bad mechanics, which is both risky and hard to test well.

Categories and Subtleties When Throwing

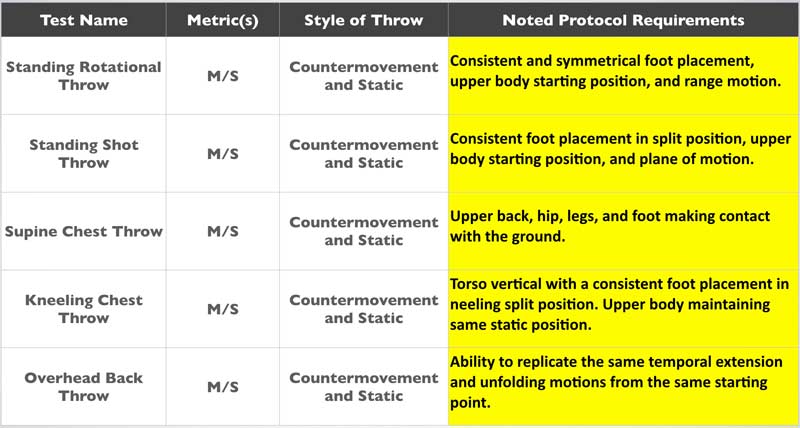

I would argue that there are a few categories to consider when discussing throwing and what tests you’ll use. First, you have to decide whether you want to test static, dynamic, or both. Then, whether you want to allow stepping, test in-place, or both. We use all variations because we can gain valuable information from each. In the descriptions of the movements below, I explain how and why you should use the variations in your protocols.

How to Test Rotational Power with Side Throws

Rotational throws tend to be either a punching action or a sweeping/scoop action. The punching action keeps the ball closer to the body and relies slightly more on the upper body, whereas the sweeping action extends the arms out away from the body, similar to a hammer throw, and usually involves a little more lower body, as in track and field events. Both movements incorporate rotation, but are far different in regard to interference with repeatability and technique.

We tend to see better quality of data with repeatability with shotput-like action, but for athletes with poor upper body strength, a sweeping action with arms straight works well. The shot version also keeps the ball from spinning too much. Often, when using the long arm sweeping version, the athlete spins the ball intentionally, which overinflates the data a bit.

Coaching Tip: I find that the shotput/punch-style throw works better with a lead step, as it allows the tester to “be an athlete.”

Video 1. The “punch” version of rotation may be more repeatable as the motion is less susceptible to body English. Comparing both the traditional rotational throw and the punch/push style may be an interesting assessment for some coaches.

Although I prefer stepping with the “punch” version of the rotational throw, I like both stepping and locked in-place throws with the long arm, scoop style. By keeping the stance “stiff,” you get more standard and reliable data. It’s fine to allow leg drive, but make sure the movement has parameters that are sensible, meaning the body shift is minimal and the leg motion is repeatable.

A seasoned athlete should be able to find a comfortable and effective stance by themselves, but a less-experienced one might need help determining this position. As a coach, you can use a symmetrical base stance or staggered depending on what you’re looking for. Experiment and come to some conclusion as to what you want to train and test and go from there. You can choose to make the stance specific or use something general so comparisons are wider; either way, have a plan for what to do later if you wish to compare different athletes.

Coaching Tip: Cueing the athlete to “throw up, slightly” will keep their ball path straighter and help to eliminate too much lateral movement.

Video 2. The traditional rotational throw uses arms that are parallel and has a longer motion. Some coaches use a countermovement, while some prefer a strict rotation starting from a still position.

How to Test Upper Body Power with a Chest Throw

Chest throws with two hands are simply underrated. I am a big fan of lower body testing, but feel that one rep maximum testing in the upper body is great for some sports and athletes, and unnecessary for others. Youth, novice, and poorly trained athletes who need to be assessed were once limited to push-up and pull-up tests. If you’ve trained any of those populations, you’ll understand that those can be just as hard as a max bench press.

Chest passes with medicine balls were great to keep athletes elastic, but as an upper body test they weren’t exciting. The Ballistic Ball has made that a moot point. They work great to complement your upper body testing or to replace it, as in the aforementioned populations.

In certain situations, a med ball chest pass could replace the bench press for testing purposes, says @ShaneDavs. Share on XBefore you lose your mind thinking I am in favor of dumping the bench press, I am not. In terms of logistics, push-ups and bench pressing can be very time-consuming and coaching-intensive. If you work with large groups and have limited time, a chest pass could be a convenient and effective replacement. I am not, however, arguing that medicine ball throwing should replace your upper body training! But as a test, it could give you some reliable and easy measurements to allow you to spend more time training than testing.

Coaching Tip: By having an athlete sit (on a box/bench) or half-kneel (pictured in video), you can eliminate most of the lower body involvement and address the upper body test as such.

Video 3. Anyone can do a good half-kneel or seated throw and it requires very few repetitions to get familiar with it. In addition to their simplicity, chest throws are fairly safe.

As pictured above, chest throws test and train well from kneeling or sitting positions and can also be done in a variety of stances to address specificity in certain populations. Another popular position, and one that eliminates all of the lower body, is the supine chest throw. By lying on your back, you can ensure there will be almost none of the data inconsistencies that come with standing variations.

Whatever variation you prefer, the chest throws are the most reliable because the ball is pushed with a very simple motion. The load and size of the ball are also great for athletes, and using a heavier ball removes many of the “micro accelerations” that come with light implements being thrown at very high velocities. Balls above 12 pounds reduce the “noise” and produce cleaner data in general.

Coaching Tip: Having a partner is important for safety purposes, but can also be utilized to add a greater eccentric “drop” when testing or training dynamic supine throws. Just don’t catch your own throw!

Video 4. Supine chest throws eliminate all lower body involvement and do a good job mimicking the bench press if that’s what you are replacing.

How to Test Total Body Power with Overhead Back Throws

My personal favorite throw is one everyone will likely love: maximum effort throws overhead. Throwing medicine balls forward (chest pass or overhead like a soccer throw-in) is common, especially with rehabilitation programs, but a true overhead back throw is a total body movement that starts with the legs. The main reason I love the throw is for the added coordinative demand it requires. If you want to see athleticism—look no further.

While testing or competing for distance is fun and exciting, the data collection is near impossible without a lot of trained eyes and space. With the ability to test velocity, you just need some high ceilings or open space and you’re good to go. As I’ve already discussed, velocity really adds a luxury and new look to the other two test categories, but with the overhead throws, recording speed is indispensable.

I especially like this test because of the simplicity in its directions and rules. Hold the ball, squat down, and throw as hard as you can. Of course, coordination and practice will help advance the test numbers slightly, but most of the improvements will come in the form of pure capacity and power.

Although simple in concept, I must warn coaches about an inconvenient part of complex movements. You must factor in movement variability and speed readings when interpreting the tests. In the past, nearly all of the data collected was with distance, a measure that requires a lot of skill by the athlete to be valid and useful for coaches. Different sports will perform uniquely with medicine ball overhead back throws compared to other exercises, so look at all of the tests before drawing conclusions. Poor launch angles would sabotage an otherwise great throw with regard to distance.

Throwing for distance is fine, but remember that you may see athletes not match up perfectly when ranked for velocity and distance separately. By replacing distance with velocity, we get a more efficient and convenient method of data collection and a rawer value as a whole. At Exceed, we like having skills to ensure that athleticism is not lost, but reliability and validity are important when testing. Like back squat tests or even jump tests, standardizing the tests requires an athlete to follow directions and not cheat.

The countermovement version is a great way to see an athlete move unrestricted. Some sports or positions would benefit from training or testing from a static position, but as an overall testing method, we prefer the countermovement approach. Fewer regulations and allowing the athlete to find their best practice will ensure that the improvements you see come from training adaptations, not testing familiarization.

Coaching Tip: Every coach loves “triple extension,” but how about quintuple extension? The vertical throw involves extension of the ankles, knees, hips, spine, and arms. Cue the athlete to throw slightly backwards for best effort. This will typically result in tremendous full body extension without the awkward back bending some athletes do when searching for distance.

Video 5. Throwing a medicine ball up explosively is another great way to see how an athlete moves. I love to follow an athlete’s ability to throw a medicine ball fast over their career.

Transfer and Capacity with Medicine Balls

With any weight room or field training drill, the transfer to sports performance is a difficult quality to prove for several reasons. The first problem with transfer is that most training programs include multiple variables, so teasing out one factor isn’t truly possible. Most training that is highly specific transfers well because the modality is within the same “species” as the sporting action. Transfer is important because coaches want exercises that have a high probability of making athletes better on the field, but sometimes capacity is just as valuable.

Transfer is important, but sometimes capacity is just as valuable, says @ShaneDavs. Share on XCapacity encourages transfer because fatigue, general strength qualities, and power are needed to keep athletes durable and resilient. Capacity is also more plastic, and can be shaped by additional specific training to assist with transfer, so the two training qualities are far from mutually exclusive. The best example is squatting heavy: While it may not guarantee that an athlete runs fast, having that capacity does show to benefit with injury rates and the ability to tolerate other training elements that may transfer nicely to sports performance.

Although I believe medicine balls help to express power better than they develop it, I don’t want coaches to dismiss medicine balls as less-effective tools. Specific sprinting and jumping are direct paths to sport and weightlifting or powerlifting can be more effective for power development, but the medicine balls are specific enough to maintain a quality during the offseason. They won’t replace your sport training or your barbell work, but they are great additions and you can include them in testing protocols to make everyone’s training better and more candid. Overall, medicine ball training is timeless and I’ve yet to see someone’s performance drop because of the equipment.

‘Throwing’ a Few Ideas Around

After reading this article, you should be more than confident that testing with medicine balls is worth the investment, but here are a couple of reasons why I love testing throws. Athletes need to get out of their comfort zone with their sport and appreciate general skills and general training. Medicine balls are wonderful equalizers because they are the perfect middle ground that all athletes can find reasonable success in.

Testing with med balls is safe and effective—you can jump right in after training with them, says @ShaneDavs. Share on XIn addition to positive feedback from honest training, ballistic throwing is popular with team coaches, making medicine balls excellent discussion points to other training needs that are not as well valued in coaches’ minds. Testing with medicine balls is safe and effective, and coaches should jump right in after a few weeks of training with them.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

[mashshare]