“How can I hit more bombs?”

“Why can’t I ever seem to find pull-away speed in the last 25 meters of my 100-meter race?”

“Can you help me dunk by next month?”

Strength and conditioning coaches everywhere can relate to being asked one or more of these questions. This article will discuss the energy system that is responsible for the explosive movements at the heart of the above questions: the anaerobic alactic system. We’ll cover the mechanics behind it, how long it can produce energy, and how it can be improved in different levels of athletes.

The difference between the anaerobic lactic (glycolytic) and anaerobic alactic (phosphocreatine) energy systems lies in the extra “a” before the word “lactic.” Alactic means that lactic acid is not produced during this type of exercise, and anaerobic means that oxygen is not needed to produce adenosine triphosphate (ATP), which is the fuel that your muscles rely on.

The anaerobic alactic system will be referred to as the phosphocreatine system throughout the rest of this article. Phosphocreatine is an important chemical that plays a crucial role in regenerating ATP during short bouts of extremely explosive movements (e.g., hitting a home run, kicking it into sixth gear for the last 25 meters of a sprint, dunking a basketball).

While the phosphocreatine system can produce the highest amount of energy in the shortest amount of time, this comes at the cost of only being able to produce energy for a very short period. Share on XThe phosphocreatine system can supply energy to the working muscles for 10–12 seconds before it has to lean on the glycolytic or aerobic system for energy production. While it can produce the highest amounts of energy in the shortest amount of time, this comes at the cost of only being able to produce energy for a very short period. If the aerobic system is a car’s gas tank, and the glycolytic system is a car’s ability to operate at its highest RPM for just over 60 seconds, then the phosphocreatine system can be thought of as a car’s 0–60 mph time.

Similar to how fats and carbs are stored in the body, phosphocreatine is also stored in the body. The phosphocreatine system does not need oxygen, fats, or carbohydrates to produce energy. This is both good and bad: good because the phosphocreatine system has relatively few moving parts; bad because very little phosphocreatine can be stored in the body, hence the quick run time of the phosphocreatine system.

It should be mentioned that the aerobic system plays a huge role in how quickly the phosphocreatine system can recover between explosive movements. Once all of the stored phosphocreatine is used up, the only way it can be replenished during the same workout is through the aerobic system. For this reason, building a strong aerobic base is not just important for cross-country runners but for any type of athlete. All three energy systems usually work together in the background during all kinds of exercise.

The phosphocreatine system is the simplest and easiest energy system to quantify and track. Any type of 1–3 rep max in the weight room can be used to assess the phosphocreatine system’s ability. Olympic lifts are preferred due to their explosive nature, but a squat and/or bench max can be used just the same. Depending on the athlete, sport-specific movements can also be used to assess and track. The distance a shot put is thrown, the time a sprint takes (100 meters or less), or how high an athlete can jump (either an approach jump or a true vertical) can all be used to measure this energy system. As long as the testing method stays consistent, there are many simple ways to test and track the phosphocreatine system’s ability.

As long as the testing method stays consistent, there are many simple ways to test and track the phosphocreatine system’s ability. Share on XAuthor’s note: Throughout these articles on conditioning, the main citation used will refer to Joel Jamieson’s Ultimate MMA Conditioning. While this book is specific to mixed martial arts, the methods discussed in it can be applied to any sport, from cross country to shot put. During my years as an athletic performance student, my mentors referred to Ultimate MMA Conditioning as the gold standard for energy system development (ESD). As I have ventured into running a year-round high school athletic performance program for various sports, I have found Jamieson’s methods to be second to none.

Before diving into the specifics of the different energy systems, it’s important to define what the broad term “conditioning” means. Jamieson defines conditioning as “a measure of how well an athlete is able to meet the energy production demands of their sport.” This means that a basketball player who can jump, cut, and shoot efficiently while still making it back on defense for the entirety of the game is just as conditioned as a long jumper who can jump and recover three or more times during a meet. Simply put, conditioning is specific to the sport at hand.

How Do You Improve the Phosphocreatine System?

As mentioned above, the phosphocreatine system is relatively straightforward and has the fewest steps out of all three energy systems. Simple = fast, which is a good thing. However, the fewer the steps in the energy production process, the less opportunity it has to be trained and improved. It’s for this reason that the phosphocreatine system is the least trainable energy system.

Similar to the glycolytic energy system, the ability of an athlete’s phosphocreatine system is largely genetic. This mainly has to do with the fact that the amount of fast twitch muscle fibers an athlete has is largely determined by genetics (Mustafina et al., 2014). The amount of fast twitch muscle fibers an athlete has correlates with the phosphocreatine system’s potential—the more fast twitch muscle fibers an athlete naturally has, the more power they can produce.

You can train the phosphocreatine system by targeting either power or capacity. Improving phosphocreatine power is mainly done by increasing the amount of specific enzymes used during the energy production process. For example, creatine kinase plays an important role in the phosphocreatine system as it helps speed up the breakdown of phosphocreatine. Higher levels of creatine kinase are found in the blood after strenuous exercise. The faster the process, the more powerful the system.

Phosphocreatine capacity is improved by increasing the amount of phosphocreatine and ATP stored in the working muscles. This is where creatine supplements can be useful. While creatine is naturally found in red meat (steak), poultry (chicken), fish (tuna), and other food sources, using a creatine supplement can help an athlete max out their creatine stores, ultimately improving their phosphocreatine system’s energy production ability.

With a simple process and a large genetic component, the ability to train and improve the phosphocreatine system is the most limited of the three energy systems, but not impossible. Share on XWith a simple process and a large genetic component, the ability to train and improve the phosphocreatine system is the most limited of the three energy systems. This doesn’t mean it’s impossible, only that the margin for improvement is nowhere near as large as with the other two systems. The methods discussed in the next section are rather straightforward and are probably already included in most strength and conditioning programs.

Beginner

Beginner athletes need to build a strong foundation of strength and coordination before anything else. As a beginner athlete, the weight room is an unexplored world with many potential benefits waiting to be discovered. These might be your incoming freshmen (at the high school level) or someone with a training age of < 1 year. These athletes don’t know what a hinge is, let alone have any knowledge of how their bodies produce the energy they use on a daily basis.

There’s no need to have these athletes do specific phosphocreatine work. The biggest thing these athletes need is reps, reps, and more reps in the weight room. Teaching them foundational movements, improving their coordination, lifting them through full ranges of motion, and improving their nervous system’s ability to recruit and use all available muscle fibers for a specific lift will be more than enough to improve their phosphocreatine abilities.

To put it simply, the stronger an athlete is, the better their phosphocreatine abilities will be. For this discussion, strength and phosphocreatine abilities can be synonymous, says @Steve20Haggerty. Share on XTo put it simply, the stronger an athlete is, the better their phosphocreatine abilities will be. For this discussion, strength and phosphocreatine abilities can be synonymous. If these beginner athletes spend 3–6 months in the weight room doing consistent work, their phosphocreatine abilities will be much improved. As long as the weight room work is appropriate and correctly progressed, they should be much stronger after a few months.

General training objectives for a properly put-together weight room program don’t need to be adjusted to target the phosphocreatine system. If the athletes are getting stronger, their phosphocreatine system is improving. Here are a few concepts to keep in mind when designing a foundational lifting program for beginner athletes:

- Time under tension: a coach’s best friend; a beginner athlete’s worst nightmare.

- Prescribing tempos and pauses with all compound movements for the first 2–4 months goes a long way in building a great foundation of strength. Something as simple as a three-second eccentric paired with a three-second pause at the bottom of a movement can make a huge difference in what the athlete gets out of the lift. The longer a beginner athlete spends in the eccentric, concentric, and isometric portions of a lift, the better their coordination and muscle recruitment will be. The more muscle fibers an athlete can recruit, the higher their strength and power outputs will be.

- Take your time: it’s much easier to progress than regress.

- Assuming you’ll have multiple years of work with these athletes, it’s important to keep a timeline in perspective. Most of the beginner athletes who come into my program will be there for four years. To put it into perspective, I tell our incoming freshmen (14-year-olds) that we have more than a fourth of their current life to commit to the weight room.

-

They won’t squat under a bar for months, and most of our movements are bodyweight-focused, with the option to progress and load as needed. If an athlete has a training age of six months and is benching with resistance bands, they’ve lost out on a great deal of progress that could have been made by simply hammering the basics. As much as beginner athletes don’t want to hear it, the weight room is a game of repetition. It might not be Instagram-worthy, but the simple, foundational work is often the most valuable.

- Don’t be afraid to let athletes who have proven themselves feel heavy weight.

- After an athlete has lifted for a few months and can demonstrate proper technique under moderate load, there are benefits to letting them handle heavy weights. Our athletes have to earn the ability to work with heavy weights by consistently showing up and showing us that they can maintain proper technique and control with moderate loads.

- “Heavy weights” doesn’t mean we let them attempt a one-rep max after a couple months of lifting. It can be as simple as letting them work up to a heavy set of three. Doing a set of 10 reps with a three-second pause at the bottom is a different type of challenge than doing a heavy triple. The heavier the weight, the higher the number of muscle fibers recruited, which in turn directly improves the athlete’s phosphocreatine abilities.

Intermediate

These athletes have proven their commitment to the weight room and can perform all foundational movements. They understand how to move their body and have been under heavy loads. They can perform proper tempo sets and have a training age of at least one year. These intermediate athletes can now move on to the next step in improving their phosphocreatine abilities: phosphocreatine capacity intervals.

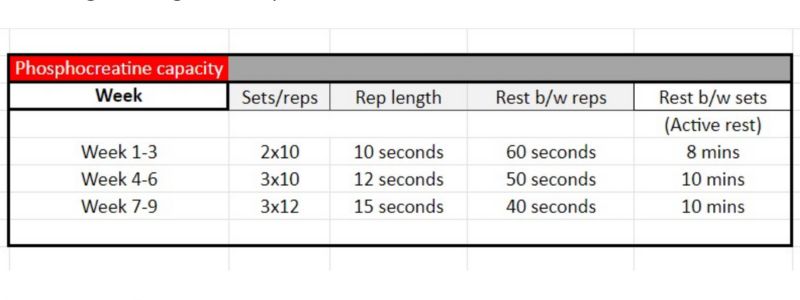

An energy system’s capacity deals with how long it can produce energy. In order to train capacity, you need to push the specific system to its limits. For the phosphocreatine system, that looks like this: 10–12 reps, with each rep lasting 10–15 seconds and each rest interval lasting between 20 and 90 seconds. Complete 2–3 sets, using one exercise each, making sure to actively rest for 8–10 minutes between sets. Active rest can be a slow jog (or fast walk), jump rope, or steady bike work.

It’s important to remember the main objective here should be to maintain maximal power output for the entire length of the rep. Training the most explosive energy system requires maximal effort for each rep. Anything under 100% intensity per rep will not tax the phosphocreatine system adequately. Performing these intervals properly for 1–3 months will increase the athlete’s phosphocreatine stores, which is one of the two discussed methods of improving the phosphocreatine system.

Training the most explosive energy system requires maximal effort for each rep. Anything under 100% intensity per rep will not adequately tax the phosphocreatine system, says @Steve20Haggerty. Share on XAny explosive exercise can be used during these intervals. Ideal exercises use the full body with easily repeatable or continuous reps. Jump squats, switch jump lunges, sprints, assault bike sprints, full-body rope slams, and plyometric push-ups are examples of exercises that would work well for these intervals. Sport-specific drills can also be used as long as they are high-intensity in nature.

While the phosphocreatine system has small margins for improvement, intermediate athletes who haven’t done any specific energy system training will see improvements. If nothing else, doing these intervals will also help improve the aerobic system’s recovery ability. If both the aerobic and phosphocreatine systems can be improved using the same interval work, that’s a true win-win.

Regardless of what the work:rest intervals look like, athletes will become fatigued during these sessions if they’re done correctly. It’s important to encourage them to work at the highest output possible throughout the session. Again, anything less than 100% intensity won’t cut it. Push through the fatigue and reap the rewards.

Advanced

These athletes have years in the weight room under their belts and have more than a strong foundation of strength. Their training age is > 2 years, and they understand how to work at maximal outputs for the duration of their training sessions. If they’re looking for ways to improve their phosphocreatine system’s abilities (which is a never-ending pursuit), a creatine supplement can help do just that.

Supplements can be an extremely attractive option for athletes looking for any type of advantage over their competition. In reality, the supplement industry is unregulated and can be a sketchy place for athletes and coaches alike. Unless an athlete has been consistently training for at least a year, I don’t recommend any supplements to my athletes. If they have at least a year of training, creatine and protein powder are the only two supplements I’ll discuss with my athletes. These are the only two supplements that have solid research supporting their benefits [Sharma, Saini, & Patil, 2022].

If they have at least a year of training, creatine and protein powder are the only two supplements I’ll discuss with my athletes. Share on XAs mentioned previously, creatine stores play a significant role in the phosphocreatine system’s abilities. Creatine is stored in muscles and combines with phosphate to create—you guessed it—phosphocreatine. The more creatine the body can store, the longer the phosphocreatine system can generate power.

Two important points to remember when discussing creatine supplements:

- The label is there for a reason. Show your athletes how to find it and interpret it.

- Human nature will tell us that if a little bit is good, more must be better. You best believe that this applies to teenage athletes who just found their first bicep vein. It’s crucial to sit down with your athletes and discuss the pros and cons of supplements, along with appropriate usage. It’s as simple as going over how to find and read the label on the back of a supplement (this also applies to general nutrition). If an athlete takes four creatine pills instead of one, the excess will be secreted through their urine. Most young athletes don’t have tons of money to blow on supplements, so explaining the “expensive pee” concept can go a long way in convincing them to use it properly.

- Purchase supplements that have been third-party tested and approved by NSF Sport.

- NSF stands for National Sanitation Foundation. It is an independent, third-party organization that objectively tests dietary supplements. NSF Sport certification is the gold standard for third-party supplement testing. As mentioned earlier, the supplement industry is unregulated, meaning companies can claim whatever they want on their labels, and it will go unchecked. With the NSF Sport certification, you can be sure that whatever is stated on the label is accurate.

- An NSF Sport certified supplement is tested for 290 banned substances and has been found to have accurate label information. NSF even goes a step further by inspecting the production process and facility cleanliness of the companies producing the supplements. In an unregulated industry, NSF serves as the lead third-party tester that ensures athletes and coaches know exactly what is being put into their bodies.

An Investment Worth Making

Out of the three energy systems, the phosphocreatine system is by far the simplest. While there is a small margin for improvement and a large genetic component to how powerful an athlete’s phosphocreatine system is, doing the necessary work to improve its abilities is well worth it.

If an athlete is working on their phosphocreatine abilities in the weight room, they’re also working on their max strength. If an athlete does phosphocreatine capacity work, they’re also working on their aerobic conditioning. Athletes who are taking creatine supplements will feel (and be) stronger and will pack on muscle mass.

All three of these examples are true “two birds with one stone” examples. Being able to produce maximal power outputs for longer periods can be the difference between being successful and falling short. Invest in the work and enjoy the various benefits.

References

Mustafina LJ, Naumov VA, Cieszczyk P, et al. “AGTR2gene polymorphism is associated with muscle fibre composition, athletic status and aerobic performance.” Experimental Physiology. 2014;99(8):1042–1052. https://doi.org/10.1113/expphysiol.2014.079335

Sharma K, Saini R, and Patil S. “A Systematic Review on the Emerging Role of Protein Powder.” International Journal of Research in Engineering and Science (IJRES). 2022;10(5):88–90.

Kreider RB. “Effects of creatine supplementation on performance and training adaptations.” Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry. 2003;244:89–94.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF