My career as a high school strength and conditioning coach has spanned nearly 30 years. Over that time, my methods, beliefs, and even things I hold as core aspects of my programming have evolved and continue to do so. Coach Mike Boyle once said, “We all think we are doing things the best way possible, or we wouldn’t be doing them. The key is to keep questioning those to make sure.”

Over the last few years, two of the most influential coaches for me have been Cal Dietz and Tony Villani. Cal’s role in my evolution as a coach has been a long, slow, consistent trickle: I watch or listen to his videos and presentations or read articles he has written and often see better ways of doing things. My relationship with Tony, however, has been more of a series of watershed moments that began with attending a clinic at Strong Rock Christian School in Georgia four or five years ago.

While Tony is probably best known for his XPE NFL Combine Prep success with partner Matt Gates and then, more recently, for his SHREDmill, what I saw that day was a thought process and method to teach our athletes ways to gain separation and use optimal change of direction techniques. Within a few minutes, I knew the way I would teach movement was going to change forever. While Villani’s Game Speed Curriculum was my initial “whoa” moment, the use of the SHREDmill to develop our athlete’s ability to maximize force in the process of acceleration is the latest.

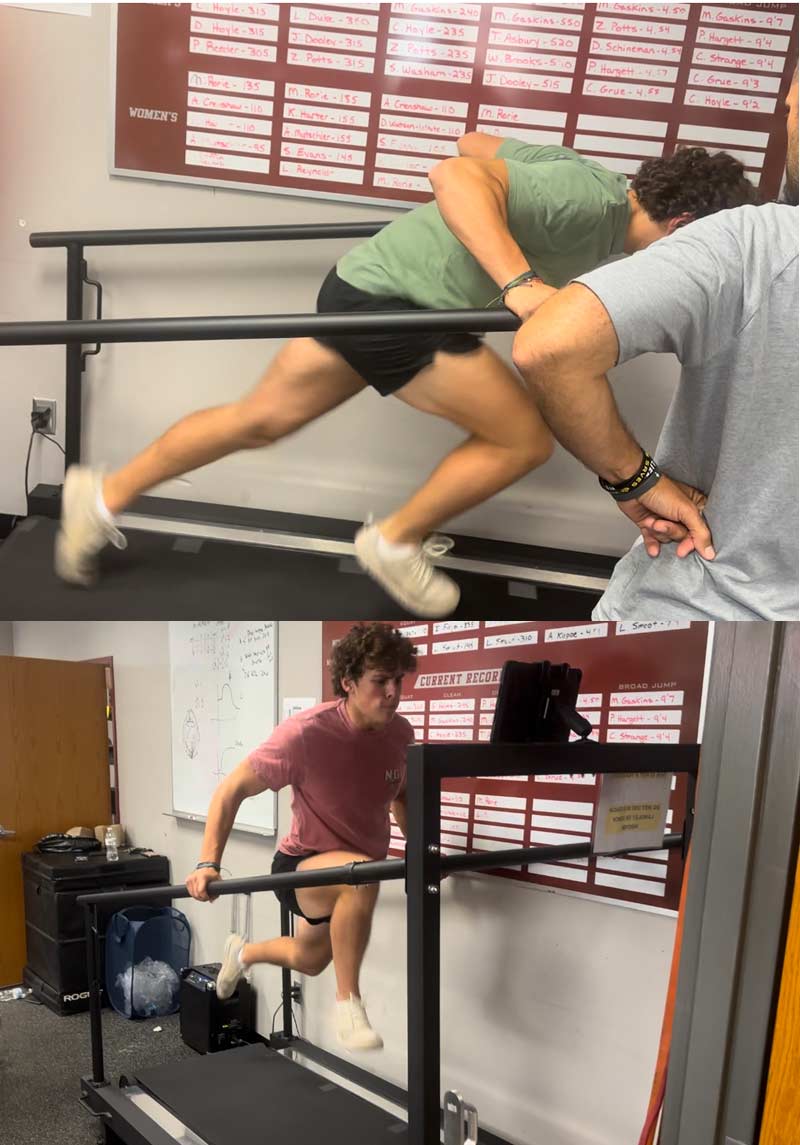

The SHREDmill helps maximize an athlete’s potential for peak acceleration and top-end speed without the need for space to sprint, says @MarkHoover71. Share on XThe SHREDmill is a self-powered speed training system that Tony first invented and used in 2011. It helps maximize an athlete’s potential for peak acceleration and top-end speed without the need for space to sprint. The SHREDmill has revolutionized how our athletes train and more than proven its value in the time we have implemented it. In this article, I will discuss our progression to Cal’s Performance Pattern Cycling Method along with the SHREDmill (and a few other pieces of technology) and how it became a powerful solution to our space and time limitations.

Finding a Solution in the Performance Pattern Cycling Method

My inspiration for this article was the overwhelming number of questions I have been getting recently about how we use the SHREDmill in a team and classroom setting. One limitation of technology in high school strength and conditioning is the ratio of student-athletes to workstations. While some schools have access to two or more SHREDmills, most facilities have just one.

This is the case at Metrolina Christian Academy (MCA) as well. While a small school (400 students), we run as many as 40–50 athletes at once through a session (a max of 45 minutes of training time). I bring up Cal and Tony in this context because a combination of protocols I have learned from both has become a standard best practice in our programming at MCA.

In addition to our limit of just a single SHREDmill, we only have five power racks. This fact was the original inspiration for our move away from a more traditional use of Coach Joe Kenn’s “Tier System” as the base structure for our sessions. At times, I found it challenging to plan for groups as large as ours, given our space and equipment limitations. The solution I turned to was one of the tweaks inspired by Cal Dietz—his Performance Pattern Cycling Method was just what the doctor ordered.

The basic explanation that Cal gives on his blog for PPCM is “cycling through different exercises in a specific order to optimize performance results…and avoid negative patterns or dysfunction in subsequent exercises” (which is outlined in detail here). Essentially, this means taking a cycle of movements or exercises and putting them in a sequence that allows coaches to build on and potentially improve the performance in later movements in the cycle. The most common example I’ve heard Cal discuss is to pair a bilateral squat movement with a cross crawl or march. This will return the athlete to the optimal unloaded linear movement pattern (optimal sprint/walking gait) that the loaded bilateral movement can negatively affect.

While you may or may not prescribe to the idea that the bilateral squat causes the gait pattern to change (not this article’s emphasis, but another worthwhile rabbit hole topic to seek out from Cal, I assure you), I have seen it to be true, as Cal suggested. I use this as just one example of many I have learned in my ongoing deep dive into Cal Dietz and his methods.

How does this help us with our limitations? We can now set up many more stations for our weight room training session. Instead of having a group of 6–8 athletes working in five racks, we can have smaller groups rotating through a wide range of movements relative to the goal for the day. We have the ability to expose our athletes to a wide range of stimuli in an order that builds on each task to hopefully multiply the results efficiently.

Cal Dietz’s Performance Pattern Cycling Method has proven to be very “tier system” adjacent and easy for our athletes and coaches to understand, says @MarkHoover71. Share on XThis method has proven to be very “tier system” adjacent and easy for our athletes and coaches to understand. It has also proved to be a driver of intent and an educational tool, as our athletes have learned that every task we assign holds great importance for the end results. The driver of that piece was the use of technology to test WHILE we train.

I’m often asked how we get our athletes to buy into things like RPR or some of the neuro-driven movements we employ. It’s as simple as providing live and instant feedback using technology. PPCM has allowed our program to run smoothly despite our space limitations. It has also allowed us to optimize strengths, such as access to a wealth of technology and the ability to provide live feedback to our athletes. One note is we do not do exactly what Cal Dietz prescribes—we have developed our own plan based on our needs, equipment, time and space limits, etc., while trying to stay as close to the core of the PPCM as possible.

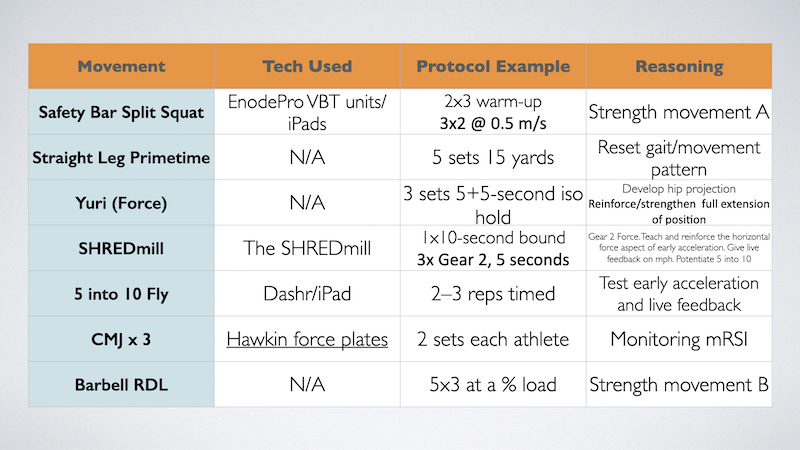

We use these cycles each of the three days we train in our weight room. For the purposes of this article, I will focus on our heavy lower body day. Here is an example of a common session: this will be after a short five-minute warm-up period utilizing RPR, spring ankle, and isometric split squats (for example):

Four Dozen Kids, One SHREDmill

We generally have about 45 minutes, maximum, to get this session in. Ideally, you would like to have the space and equipment to start each athlete at a safety bar split squat and progress from there. When we have a smaller group training, we do this. When we have a group over 20, we assign each group to a movement as their starting point. As they finish, they move to the next movement in the exact order. This is one of the issues we had to work through.

The athletes naturally wanted to race through and skip something or go back to it. We really had to reinforce the thought process of “If you are done before the group in front of you, rest!” Our goal is normally five sets of our strength lifts. You will see above that we have fewer sets prescribed for some. This is really a result of trial and error. After almost a year, we have narrowed down a method that works for OUR situation. We know we will almost always be able to finish that circuit in our prescribed time when we use this.

We quickly did away with the clock. We found that once the athletes understood the process, we could let them drive the circuit, and we could coach, says @MarkHoover71. Share on XAt first, we tried to use a strict timer for each. This may not sit well with some of my more organization-driven colleagues, but we quickly did away with the clock. We found that once the athletes understood the process, we could let them drive the circuit, and we could coach. Our athletes handle the iPads and understand the process to work as a team to change names and use all of our technology and the SHREDmill.

The SHREDmill is especially easy to use. Our athletes sometimes use a personal three-number code that keeps track of their metrics in the cloud (if it’s an assessment), and other times use free run mode (no code, just set the time and go). We have found that once the athlete memorizes their three-digit code, there is no time lost compared to a free run. Every 5–10 athletes (on average), the belt may slide one way or the other (based on how the athlete pushes). It is a quick and easy process to reset it with your foot and be on the run. We have taught our athletes how to easily adjust the belt as needed by using their foot to push the corner into alignment. Beyond that, there is little to no setup between reps.

This allows me and our coaches to have little involvement in that aspect, freeing us to be present and coach. The intent that the competitive atmosphere of live feedback builds has been incredible and yielded results that I never imagined we could see. One immediate example comes from our 5 into 10 fly data. Before SHREDmill and the full-fledged PPCM, we considered a 1.28-second time good for males and a sub-1.25 excellent. Those numbers are now common for all but very large or very young athletes. It now takes a 1.21 or below to break our leaderboard, and we have had an athlete hit 1.13 and 1.14 (he also ran a 6.29 sixty at a national baseball event).

The intent that the competitive atmosphere of live feedback builds has been incredible and yielded results that I never imagined we could see, says @MarkHoover71. Share on X

The reason I point that out is not to compare our program to anyone else’s. When I took the position at MCA and did an across-the-board evaluation of athlete needs, the top need was to improve early acceleration and decrease the time needed to reach a high percentage of max velocity. We developed our program this year to make this a priority. Tony’s influence in this area not only provided us with the ability to see great improvements in horizontal force production, which transferred to improved early acceleration, but it also led to incredible improvements in max velocity miles per hour—this despite the minimal use of any max-velocity mechanics drills in our field and court sport preparation. Instead, I compare it to where we started and hopefully help others in a similar situation to also see improved results.

If you don’t have the technology available, it’s very simple to replicate with less or none. We test our vertical jump (a different day) on a Skyhook Jump mat. A jump mat can be used and produce similar results from an intent and feedback perspective. If you don’t have VBT? You can do timed sets, as I wrote about in this article.

My final takeaway for you is to say that the targeted use of PPCM is just my solution. Your solution may or may not be the same. My advice is to read, study, and grow. The knowledge you acquire will be in your back pocket and allow you to take inventory of what you’ve learned and quickly apply those solutions. PPCM and the SHREDmill are powerful tools in my inventory. However, with or without access to technology, your growth mindset can offer a solution that can help you make the best out of any situation, regardless of constraints and limitations.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF