From what I’ve gathered thus far in my career as a strength and conditioning professional, the observation and adaptation of our programming must work in tandem with the observation and adaptation of our athletes.

The challenges that the emergence of COVID-19 presented to strength and conditioning coaches—as well as private performance facility trainers and coaches—was almost overwhelming. When reopening my training facility and also eventually returning to the high school I previously coached at, there were constraints outside of the actual training that I had to address from a function and time-use standpoint: no indoor usage early on, athletes masked for a period of time, and 45-minute time restrictions weren’t ideal by any stretch of the imagination.

Thankfully, I was using my “off time” (technically unemployed for 3.5 months) and was exposed mentally and physically to some great methods that swung the pendulum back in our favor.

Applying Models

The keys to any successful program include:

- Knowing your athletes/sports.

- Knowing the training goals.

- Understanding all variables and limiting factors (space, time, equipment, participation numbers, etc.).

- Understanding progressions and regressions of all programmed exercises and movements.

- Keeping it simple.

Over the last several years, while working in both the public and private sectors, I had adopted the Tier System created by Coach Joe Kenn as the primary format for all the athletes I worked with.

To give a quick synopsis of the Tier System, it’s quite simple and highly effective for the development of athletes:

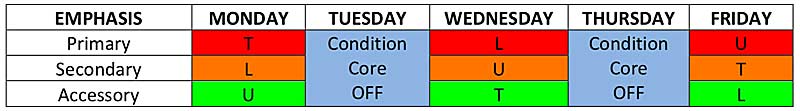

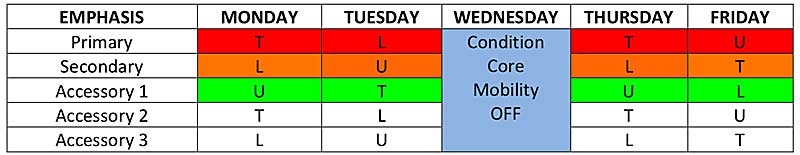

- A “whole-body” weekly alternating rotation of total body (T/t), lower body (L/l), and upper body (U/u) focused training days.

Depending on training phase, experience, season (in or out), and other training variables, this template can be expanded to a more detailed and complex plan.

The system’s simplicity and effectiveness alone sold me almost immediately. And the fact that it had been developed and tested well before I was even in the field was the icing on the cake. Coach Kenn published The Strength Training Playbook for Coaches in December 2002, and it still stands the test of time almost 20 years later.

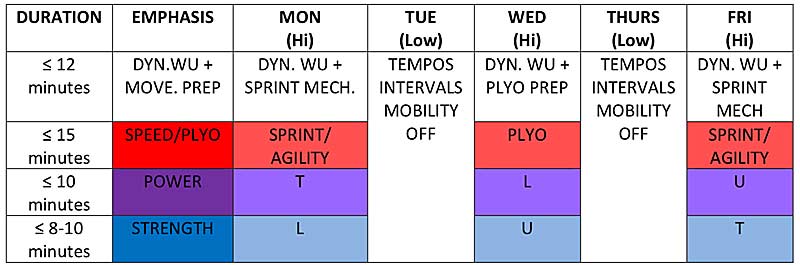

COVID-19 presented a couple of problems that threatened continued progress. One in particular was time, says @KoachGreen_. Share on XBecause of its straightforward structure, I was also able to incorporate the High-Low Model popularized by Coach Charlie Francis (see figure 1) and participation in Coach Mike Tucker’s “Sprintember” in 2020 and 2021.

But, as mentioned above, COVID-19 presented a couple of problems that threatened continued progress. One in particular was time.

Program Shift

As practitioners, we understand (or at least we should) the S.A.I.D. principle, the demands of individual sports, and how to adjust certain training protocols and modalities to create physiological adaptations. But for some reason, every program I’ve been a part of since I was an athlete in high school seems to separate field/court performance qualities (primarily speed and agility) from the rest of training. In some cases, it’s understandable: too many athletes, not enough staff, not enough space, etc.

What that often looks like is:

Total Training Time = 60+ minutes

When time and space wasn’t an issue—pre-COVID-19—this format was sufficient. But in current times, when many strength and conditioning professionals have to follow more restrictive guidelines, I would like to propose a better solution. I’ve coined it the SPS Model (speed, power, strength).

Before I continue to state my case, I would like to remind readers that there are very few new or original ideas in strength and conditioning. The Bob Alejo quote “tell me what it is, and I’ll tell you what we used to call it” rings true. That being said, I will take my liberties and refer to it as the “SPS System.”

The SPS System

The objective of developing and utilizing the SPS System is simple: take what works and is absolutely necessary and discard the rest.

Here’s what it looks like, and then I’ll break it down:

Total training time = < 50 minutes

Time, as a significant factor for all things human, was my primary driving force. In the public sector, as mentioned before, teams were limited to 45-minute sessions because of the need to split the team in half for spacing purposes. Using the SPS System with a football team under these conditions, we were able to split the team into “Bigs” (linemen) and “Skills” (non-linemen), giving the linemen earlier access to the weight room and giving the skills more field time.

In my private facility, there was a little more flexibility as far as duration goes, but because my space is limited (1,400 total square foot facility with approximately 1,100 square feet of usable space), group times—particularly high school and college groups—had to be separated to give individuals options to come at different times to limit congestion. This time separation allowed the training groups to go from 6-8 athletes at a time to 3-5. Profuse cleaning of all equipment after each use was also an additional, necessary time-suck.

Taking the overall structure of the Tier System, the foundation and weekly flow of the High-Low model, and the methods and protocols of “Sprintember,” we have found what seems to hit the “minimum effective dose” and “maximal recoverable dose” on the head.

We have found a system that seems to hit the ‘minimum effective dose’ and ‘maximal recoverable dose’ on the head, says @KoachGreen_. Share on X

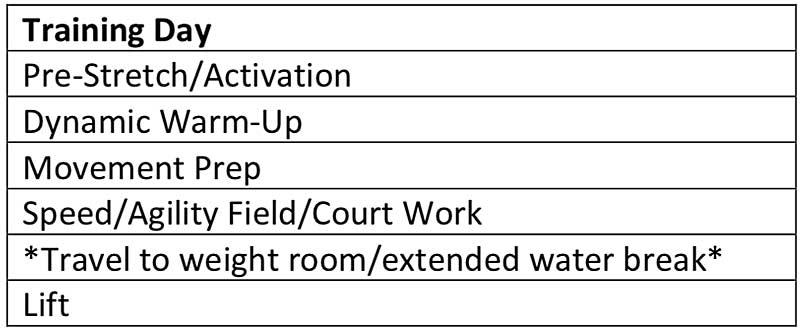

This 3 × 3 (in Tier System terms) Hi-Lo cycle begins with a Monday high-intensity day. Along with this new model, we’ve found that most, if not all, of the athletes we work with don’t need any pre-activation or stretching (e.g., foam rolling). That being said, we start with some type of warming activity—jumping jacks, jump rope, bike ride, etc.—and go straight into our dynamic warm-up.

We change the dynamic warm-up quarterly throughout the year, so there is no mystery or nuance to it, making it easier for us to blend the movement prep into the session. This process from warming to prep takes less than 12 minutes on average.

Movement prep for speed and/or agility days consists of one or two drills from the A-series (Mach drills). We perform these from traditional and nontraditional positions, depending on the activity for that portion of the session. On plyometric days, the movement prep normally consists of various lower-leg priming movements that gradually increase in amplitude, intensity, and volume. This portion of the session takes about five minutes.

Moving from movement prep into what I believe to be the crux of the training session, we get to the “S”: Speed (agility/plyo).

You may be questioning the use of plyometrics in the same place as speed training on non-sprint days. It has become more evident from data and real-time observation that the fastest athletes are usually capable of jumping the highest and furthest, and the athletes who jump the highest and furthest are statistically faster—keeping in mind vertical jump-ability is relative to body displacement, while horizontal jump-ability is the second-best display of horizontal power (second only to sprinting). Therefore, the two are categorized into the same performance quality.

Speed and agility—time of year and training phase will determine which takes precedence—training for field and court athletes is one of the primary reasons I am eager to share this system. The highest priority for any athletic performance training program should be the activity that is nearest, or most transferable to, the actual sport. For field and court sports, that is speed and agility (as it relates to a specific sport).

Speed and agility training for field and court athletes is one of the primary reasons I am eager to share this system, says @KoachGreen_. Share on XIn this “S” training session block, we do anywhere from 3-8 sprints of 5-30 yards, and we laser-time as often as possible (Dashr), particularly during the summer and off-seasons. For plyometrics, athletes execute 4-12 jumps (reps/sets dependent on jump variation and number of ground contacts). This segment takes no more than 15 minutes.

After taking care of our primary (or Tier 1) training focus, we can execute the physiological qualities that enhance the primary’s function and capacity. In the case of our general template, Monday is a total body, power focus day followed by lower body strength. Our secondary focus is either a single power exercise, separated into a contrast set, or a major-assisted set (major movement superset with an assistance or mobility movement). Strength is programmed in the same manner. With this format, there are no more than five actual lifts per session.

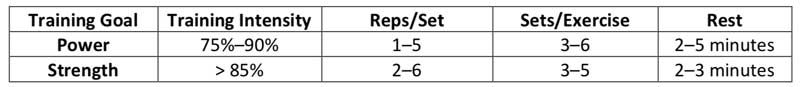

The reps and sets for the “Power” and “Strength” portions of training simply follow the training goal continuum guidelines.

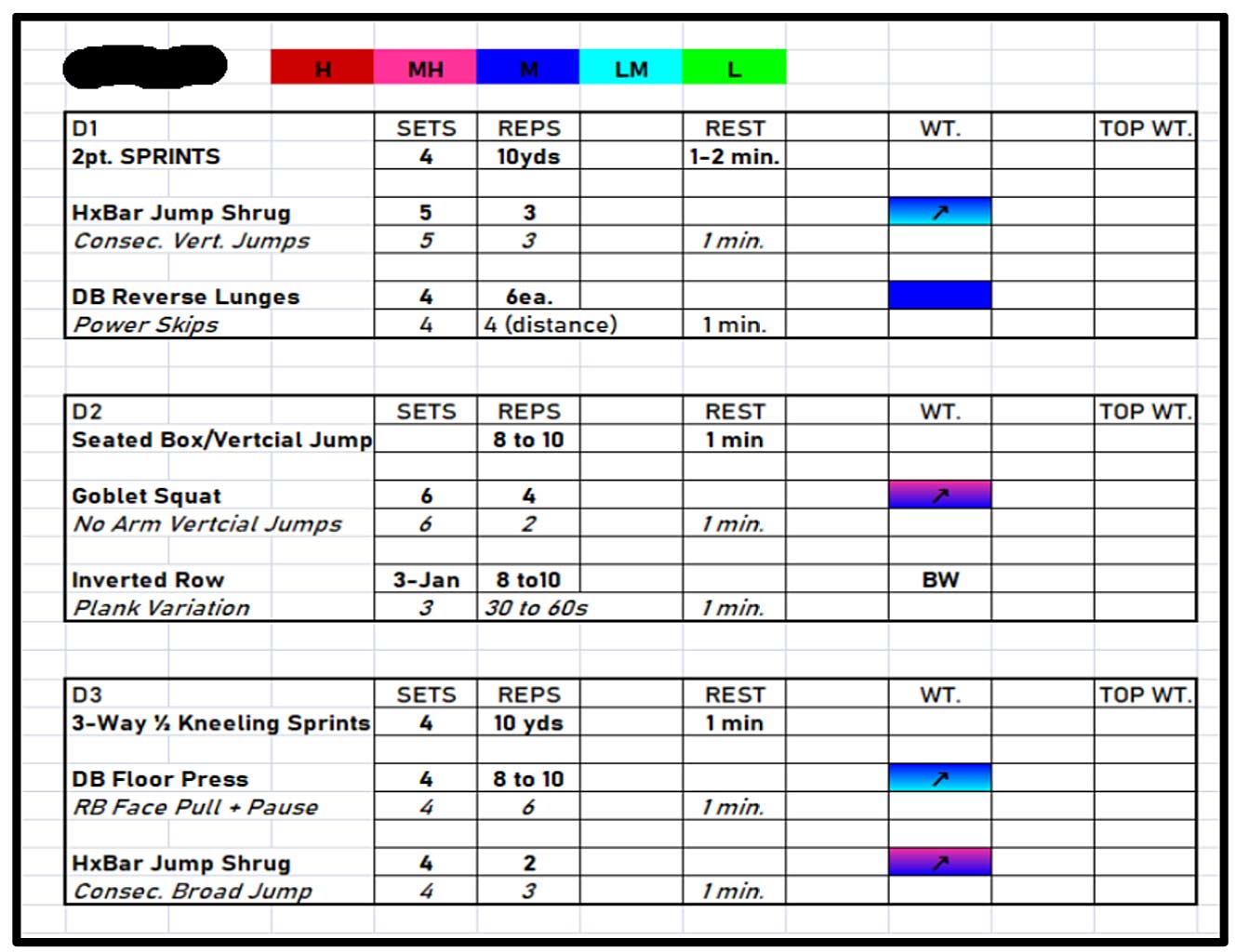

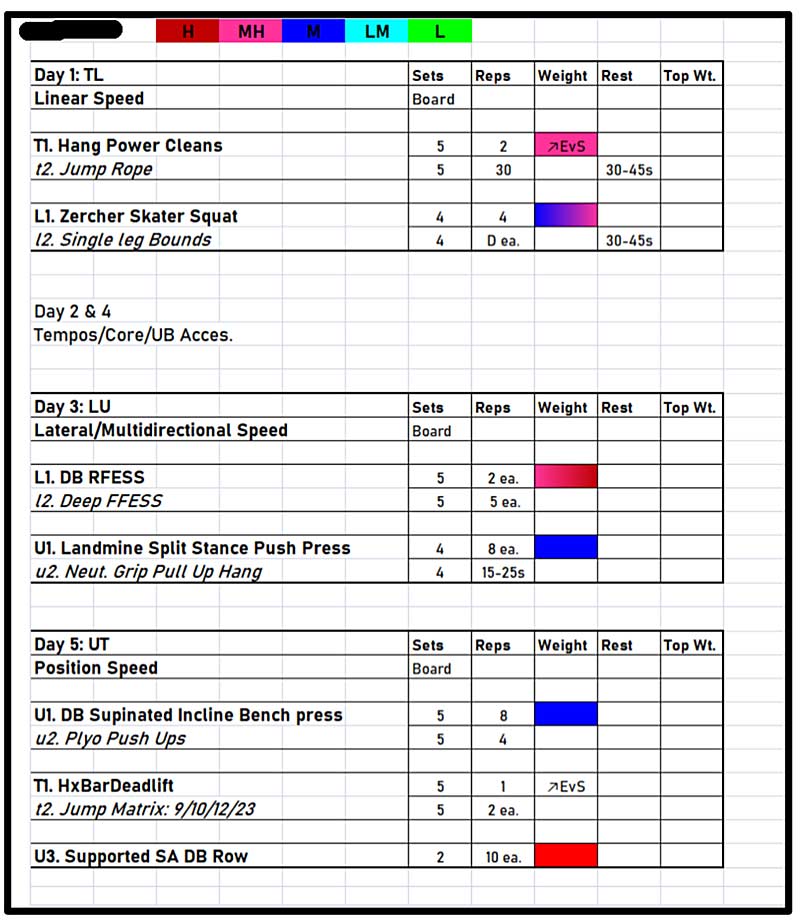

Now that I have broken down the system’s objectives, flow, and function, here’s a week of training that was programmed for the summer volleyball group and another programmed for an individual football player post partial MCL tear preparing to enter his first year in college:

This system is not meant to be groundbreaking or a replacement for any existing programs. The intention is to provide a solution for coaches to pinpoint exactly what is needed within their training to optimize training time and maximize results. Doing so will prioritize exactly what each individual and team needs to succeed.