How do you train your athletes in season? It’s a question that most, if not all, coaches have been asked many times. It’s one that most of us will answer with our own twist on exactly how we go about it.

There are many factors that go into how we plan that aspect of our programming. When I’ve been asked this question in the past, I’ve answered that we use a very common protocol. We begin with moderate volume and load, and as we progress toward the post-season, we gradually decrease volume while simultaneously increasing load.

As our plan was laid out, we would actually hit near maximal and, if possible, above maximal loads from our preseason testing. Without a doubt, you can attain positive results using this type of programming. The dynamic can change, however, when you work with large groups of athletes. In my years of programming this way with team sports, the problem was that what we programmed and what athletes actually did too often varied. No matter how much we, as coaches, urged or demanded that our athletes do heavy (85%+) singles and doubles on the back squat or trap deadlift during the 14th week of the season, we still had trouble getting that accomplished across the board with all athletes.

The bumps and bruises and fatigue athletes feel can lead them to choose which aspects of training they “believe” they can accomplish and which ones they can’t, says @YorkStrength17. Share on XThe bumps and bruises and fatigue athletes feel can lead them to make choices about which aspects of training they “believe” they can accomplish and which ones they can’t. Often, it’s hard for athletes to understand that you have programmed their in-season workouts to work with practices and increasing sport volume. In my experience, the movements for which I would hear, “I can’t do that much right now” (when we knew that physically they could—they should have said “I don’t feel like doing that”) were back squats and trap deadlifts. Bench press, on the other hand, was no problem. I rarely, if ever, had to get on one of our football athletes for not loading sufficient weight on the bar to bench. In fact, usually it was quite the opposite.

Sure, we could “force” them to do it by standing over them and demanding it. Would they get anything out of that in the mental state that moment would lead them to? Probably not. There had to be a better way to get full participation. The problem had me searching for answers. If the athletes don’t follow the programming, the results will obviously not be maximized. How can we get our athletes to use the proper loads, without standing over them and counting the plates as they load the bar? How can we ensure that they not only stay strong as a season moves ahead, but that we also get maximum transfer from training to field?

Yes, many high school athletes will do exactly as you coach them to do. We also know that the majority of them will do what they believe they should do in that moment.

I set out to come up with a way to maximize our in-season program. What we came up with ended up changing my way of thinking. It kept our athletes strong and explosive across the board, producing post-season testing results that, while just a one-year sample, made us never want to look back. It’s something that I quickly began looking forward to writing about and sharing.

Our process was not revolutionary in any way. However, if you’re a high school coach with similar issues, I’m writing in the hopes of giving you insight into how we not only improved, but took our in-season training program to new heights.

Max Speed

I’ve written in the past about what a great tool velocity-based training (VBT) is for athletic performance. My initial thought process was to use VBT as our way to program in-season. There is no doubt that training with maximal intent transfers to athletic performance. Research has concluded that training with max intent was “a fundamental component of training (for athletic transfer) as the velocity of the loads lifted largely determines the resulting training effect and causes significant increases in both strength and power.”

Using a VBT device will obviously help the athlete to train with max intent. It can also allow you to do away with percentages and use the much more reliable metric of speed in m/s. I’m a huge advocate of VBT. In fact, with a small group, I’d still lean very heavily on it. But what if VBT is not an option? Not everyone has access or time for it.

In this particular situation (a varsity football team), it wasn’t an option for me. The group was simply too large and the time we had to train too short to utilize VBT as a training modality. How can we train athletes to move the loads sufficiently to lead to the adaptation we, as strength coaches, look for, but with maximum intent that will transfer without VBT? The answer was very simple, and it was right in front of me.

Velocity Without an Accelerometer

Sitting down to figure out this problem, I remembered a conversation about VBT I had with Coach Johnny Parker. He told me that they’d been using VBT for a long time—even before the widespread use of a “fancy monitor.” They used a monitor, he said: “it was called a stopwatch.” After all, what’s velocity? It’s timing how fast something moves.

If we get athletes to move increasingly heavy weights at the same speed or with faster times, we utilize the positive aspects of VBT. I decided that was where I wanted to start. I began to formulate a plan to execute this in programming. I understood that hand-timing sets would not be the exact science that VBT is, but I also understand what adding a timer does to anything we do with athletes. It leads to max intent, which is what we wanted to get out of our in-season program.

I understood that hand-timing sets wouldn’t be the exact science that VBT is, but I also knew that adding a timer would lead to maximum intent from athletes, says @YorkStrength17. Share on XI was further encouraged after a second conversation I had in June at the NHSSCA National Conference. I ran my ideas by David Abernathy. He not only approved of them, he said he had found himself in similar situations in the past and had experienced great results from training this way.

Empowered by the research and my conversations with two highly respected strength coaches on the topic, I sat down to formulate a plan to maximize our athletes’ in-season experience.

The Plan

What we came up with was a mix of the traditional way we had trained in-season and maximal intent training. I still am a believer in decreasing volume and increasing intensity as the season moves forward. I knew I wanted to keep aspects of heavier training in the program.

We kept bench press, as we had always trained it. That never has an issue of load being too light with American football players. On the other hand, we would adjust our pulls and squats. If we could find a way to get stronger using lighter loads with those movements, we would be ahead of how we had trained in the past. There is no other way to put it: As athletes get further into the season, it gets tougher to get them to move appropriate loads on those two movements. This could eliminate that issue while rendering the athletes even more able to develop power.

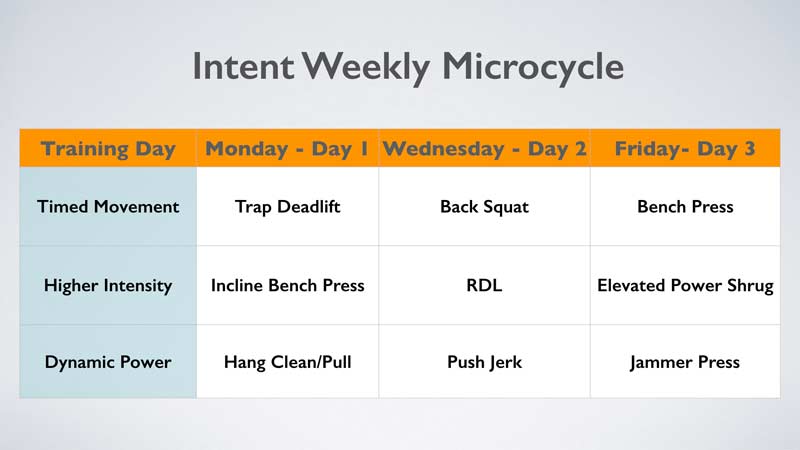

If we could find a way to get stronger using lighter loads with pulls and squats, we would be ahead of how we had trained in the past, says @YorkStrength17. Share on XFor each of our three days, we programmed one speed-based movement with a lighter intensity and one heavier movement. We met the athletes where they were instead of where we hoped they would go. For movements we felt that athletes would naturally push themselves on, we programmed higher intensities. For others, we used moderate loads at higher velocities to force strength adaptations.

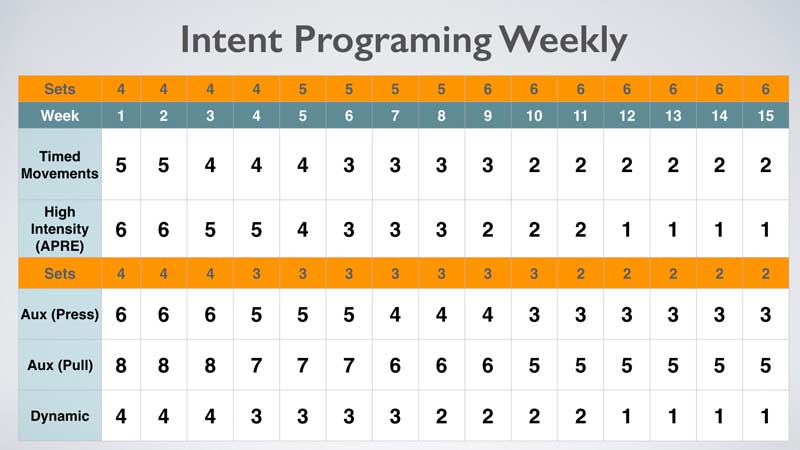

Our sets and reps programming stayed fairly consistent with past seasons. With our timed movements, we started with four sets of five reps. With our higher intensity movements, we began with an APRE6 protocol. We worked our way down with volume, until we were using six sets of two for timed movements and six sets of one for higher intensity in the final week of the season.

The way we programmed intensity was something brand-new to me this year. For our timed movements, we put our athletes into groups of four based strictly on the 1RM of each athlete. I then loaded the bars on week 1 with the average of the four athletes’ 55% of 1RM. I selected this weight because it was low enough to ensure proper movement at top speed in the higher rep ranges that we’d started with. It also allowed our athletes to really experience max intent. They were able to make that load “hop,” and this taught them what top speed felt like.

From that point on, each week I loaded the bar for each group and added five more pounds to it. Every time we dropped volume (example from 4’s to 3’s), I added 10 more pounds from the previous week. I did this after I counted back from week 15 to week 2 with an “average” of 75% of 1RM per group. This allowed us to move from (+/-) 55% to 75% over that time.

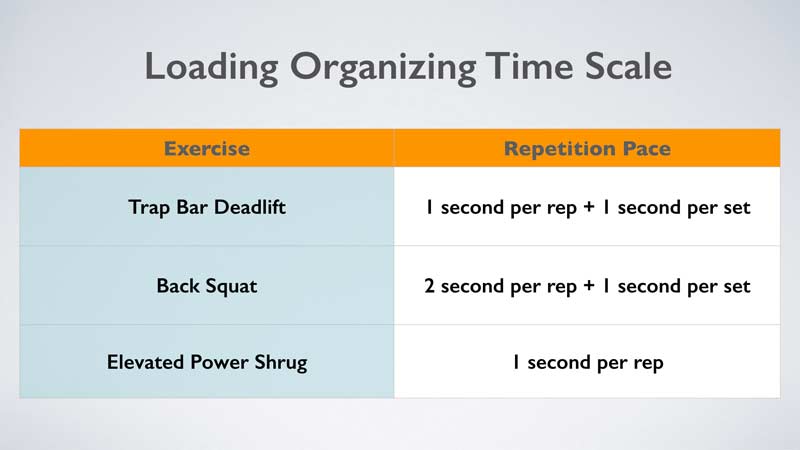

I kept the speed per rep goal (stopwatch-timed) the same from start to finish. I knew they’d be able to move faster than the goal at the start of the program at 55%. Our goal was to keep the approximate velocity of the movement the same as our load increased up to +/- 75%. If we could achieve that, we knew the power output would increase and transfer those reps to the field even more effectively.

Our third timed movement was elevated power shrugs. We used blocks to get the trap bar 12–18 inches off the floor. The athlete basically did a loaded jump type movement without leaving the floor. Load-wise, we used 50% of the weight used for trap deadlift that week.

Pre-loading the bars was a new thing this year, and it was a lot of work for me because we have 15 stations. But the benefits were well worth it. Our athletes were able to come in, warm up, and get started. It saved a lot of time. The less the athlete has to think, the better it is. This took thinking out of the exercise.

Pre-loading the bars was a new thing this year. Our athletes were able to come in, warm up, and get started. It saved a lot of time, says @YorkStrength17. Share on XI loaded the bar with a base weight that they would use for the first set. I set the rest of the plates on the floor. After that first set, I told them to load the plates I laid out for them. If a group didn’t load the correct weight, our coaches easily spotted it. This added efficiency to the process. The time we used per rep ended up as follows:

With our auxiliary and dynamic movements, we used a more athlete-controlled protocol. Using an APRE-like program, we had them climb to the weight they did the previous week for their next to last set. They were able to adjust their load for the last set based on that set’s outcome and how they felt.

From a set timing standpoint, we began at a point where we were almost going too fast. I ended up extending rest time so that each athlete went off a 30-second whistle. The athlete would finish his set in 2–10 seconds. At the 20-second mark I’d yell out “next man up…,” at 25 seconds I’d say “ready,” and at 30 seconds I’d blow the whistle. This got us through our six-set exercises in 12–13 minutes whistle to whistle.

Max intent with efficiency was a direct result of our programming. It was also very high energy, says @YorkStrength17. Share on XMax intent with efficiency was a direct result of our programming. It was also very high energy. There was no time to lose focus. As a coach, I was very involved. It allowed me to set the tone for every set. It also allowed me to adjust set and rest times based on the team lifting that day.

Developmental Athletes

Initially, we had to make one main adjustment to our protocol. This was with our “developmental” group. In most sessions we have at least a few sub-varsity athletes training at the same time. These players were all sophomores. They were a year into the program, but they were not where we wanted them to be yet. That presented a problem.

For one, those players didn’t all back squat or do hang cleans yet. Another factor is that, many times, those athletes are further from what we call their “strong enough” level. As I’ve written about in my article series on blocking our athletes, we have frame/bodyweight goals for each athlete to reach that we consider “strong enough” for what they need to be able to do on the field. Our approach to strength training with these athletes is different than with our younger groups.

We needed to find an adjustment that allowed those developmental athletes we had working with the varsity athletes to be on a more traditional path to strength. First, we tried to have them work as a separate group, but this didn’t work out for us. We wanted them to be part of the high-energy program we had developed.

What we ended up doing was keeping that whole group on sets of five reps. We did not time that group; however, they did stay within the timed rest parameters, and they did start on the whistle. They just had a consistent rep assignment while still increasing intensity each week. As we got toward the end of the season, we even extended the rest time because of this group. The extra rest time was a good thing as we approached our higher intensity goals with the varsity players.

We let the sub-varsity players have more freedom in adjusting weight as well. Our goal for them was get to five reps with “one left in the tank.” We still had a bar-speed focus with this group. However, with sub-varsity level athletes, we feel closing that “strong enough” gap was more important than max speed. Also, younger athletes tend to get less from the types of speed we use with our varsity group because they are not as technically sound with the movements. Velocity without technique is kind of chasing your own tail.

End Results: An Encouraging Protocol

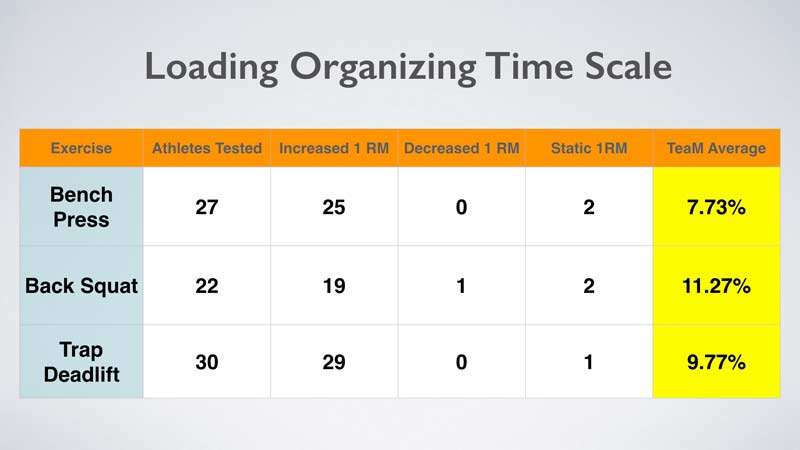

Although not a study to a scientific standard, the data I collected from pre and post testing our varsity football class is highly encouraging and leads me to want to continue this protocol. We tested pre-season and retested the week directly following the end of the football season. None of the athletes included in this data were from our developmental group. The data group were all athletes we identify as “Block 3” or “Block 4”—seniors, juniors, and a small handful of advanced sophomores. Each of these was at least within 86% of the “strong enough” frame/weight threshold I mentioned earlier. Each of these athletes also had a proficiency in the movements tested in order to earn promotion to either Block 3 or 4.

Our bench press numbers showed a slight increase, and our squat and trap deadlift numbers far exceeded 2018 testing and the goals I’d hoped to reach, says @YorkStrength17. Share on XTable 4 below shows the final data gathered from that testing. As you can see, we were able to achieve a high level of strength increase from both individual and team standpoints. Going in, I really hoped for a 5–7% team average with 75% of our athletes increasing in back squat and trap deadlift. Those were numbers I selected because, looking at last year’s testing, those would have been improvements. Our bench press numbers showed a slight increase from 2018 in team average and athletes increased. Our squat and trap deadlift numbers far exceeded 2018 testing and the goals I had hoped to reach.

In addition to increases in testing data, we saw a significant increase in total player training days. In 2018, we rarely, if ever, had the entire team training any single day. Many factors led to this. We were basically free of soft-tissue injuries in 2019, with just one athlete missing game time with any type of soft tissue issue. We only lost two games due to varsity football players with concussion symptoms. We also had a change in head coaches and an ensuing change in culture, with a focus on in-season training being a non-negotiable issue. In the weight room, we had zero injuries.

From a completely anecdotal standpoint, it was also clear by watching our players on Friday nights that they moved more explosively than they had at points in the previous season. I should also note that these results came at a point in our football program where we were in the first year of a total program rebuild. Our 2018 squad was much more experienced and talented athletically. This protocol played a role in giving our younger, less-experienced 2019 squad a chance to maximize their potential and set themselves up for a 2020 off-season that sees our program lose a small handful of players and return a large number of starters.

The Takeaway: Speed and Strength

I’m hoping my experience in problem-solving an issue in our sports performance program will, at the very least, give you options if you face similar problems in your program. As I’ve grown in the field, I’ve become a proponent of the idea that the goal of training for athletics is to be faster, not necessarily stronger. Speed is what transfers to sport. However, we all know that strength is a major component of allowing athletes to maximize athletic performance.

The combination of the two produced results for our athletes. Movement velocity seems to be of great importance for inducing strength adaptations directed toward improving athletic performance. Although this was understood in our program previously, it’s clear that placing a focus on speed with submaximal loads in order to produce concentric movements at peak velocity is highly effective, not just in-season, but as part of a yearly plan.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF