Low repetition ranges and heavier weights in-season work for every sport. Maximum contractions at low volumes achieve better strength levels by the end of the year and reduce the in-season soreness and fatigue which results from training programs that are too high-volume. I’m also convinced that most in-season injury comes from a lack of strength and, at the least, a lack of training intensity.

Raise your hand if you’re tired of hearing “in-season maintenance program.” Anyone? Mine is raised. I first encountered the concept when I came to Major League Baseball (MLB) with the Oakland A’s in 1993. It was a phrase used to describe in-season strength training programs as if it was one word, inseasonmaintenanceprogram. I’d heard this term before but not a good explanation for what it meant. And I’m all about the why.

I decided never to use this term and learned to better explain the idea from an exercise science and sport perspective. This article explains the result: my in-season training programming philosophy for baseball. Or any sport, for that matter.

The Evolution of My Strength Training Program for Sport

During my start with Oakland, the in-season strength program began with a repetition range of 8-12 reps spaced out over the six-month MLB season. I’m generalizing here but, for example, 8 reps for a few weeks, 10 reps for a few weeks, back to 8 reps, then 12 reps, and so on for six months. Two to five sets generally for each exercise. The exercise selection had a well-rounded menu from A-Z: squats, deadlifts, dumbbell work, pulleys, med balls, etc., to which I didn’t take exception.

I did, however, question the repetition range for strength. While there was certainly enough documentation as well as popular practices regarding repetition ranges for strength, the particular coach I was working with believed strength would be a byproduct of 8-12 reps. Also, the players didn’t want to lift “heavy” weights during the season.

I also was concerned that the players would get sore from performing this high-volume rep range or, at the least, burn-out from fatigue. Baseball is an everyday proposition. When we included lifting or conditioning on game days (in-season programs for athletes that included running weren’t popular then; much improved today), fatigue and soreness tied for first place on the list for taking caution. I was told that the load was submaximal and, thus, neither soreness nor fatigue were issues.

Through this questioning process, I started to build my stance on in-season training, maintenance, high repetition, fatigue, soreness, and injury management.

Repetition Ranges for Building Strength

Where a 1RM is the guideline, the 8-12 rep range does not fall into the strength zone. Most coaches suggest that 5 reps should be the top end of the zone. I’d argue that the range should be 1-3 reps. One cannot maintain the highest absolute strength with an amount of weight with which one can’t acquire the highest absolute strength.

Historically the 8-12 reps range is used to put on muscle. But, because there exists a sensitivity to athletes being sore or fatigued, the weight used is submaximal with submaximal effort. This provides only a slight chance of both putting on muscle and maintaining muscle mass. And, therefore, there’s no chance of maintaining strength.

In a normal periodization scheme, as the year progresses toward the competitive period, the emphasis shifts from training to skills and strategies. Simply put, practices and competition make up the bulk of the schedule and the time for training diminishes. Baseball is unique with games played nearly every day. If you consider the entire year, including spring training, there are more than 190 games in roughly 210 days.

A baseball player has to train on game days, before or after the game. The times of the games make it difficult, but not impossible, to lift or run before the game. With batting practice at 4:30 pm for a home game, any early work the player has to do (film, treatment, rehabilitation, extra hitting, or defensive work) has to be carefully planned so the player does not feel fatigued for the game.

Aside from the starting pitchers and relievers who weren’t available, the majority of my guys lifted after a game. I wanted them to lift heavy, and I believed that was best to do that after a game–if not for maximum poundage, certainly maximum effort. If I was a player lifting before a game and knew I was facing Kershaw, I couldn’t put in the gut-busting effort needed if I wanted to catch up to his “gas” (fastball), to say nothing of his slider. The game comes first.

The Goal: Decrease Strength Loss In-Season

Time constraints are a scheduling problem for in-season training.

By mere frequency and duration, maintaining strength during the season is almost impossible. However, decreasing the amount of strength loss is very possible.

Maintenance is an unlikely in-season strength training philosophy or fact for the MLB. The competitive season, which is longer and more difficult if you make it to the post-season, will get athletes no matter what. Players are going to get slower, weaker, and fatigued due to the physical and mental intensity it takes to compete at their best during the everyday grind. My goal is to have my guys be less slow, less weak, and less fatigued than the other team. Basically, I take the graph of naturally declining physical qualities and try to flatten it out a bit.

Younger Athletes. We need to qualify the concept of maintenance when talking about athletes who are deemed weak or those whose chronological training age is very young. I’ve had freshmen basketball players–even those playing 20-30 minutes per game–routinely gain strength and power (meaning standing vertical jump increases) from baseline pre-season testing when assessed during and at the end of the season. I expected it. Following my philosophy, I concentrated on strength and did very little ballistic work which physiologically makes sense for the physical level of these athletes. I did not back off from their training (fewer higher intensities during the season) as I might with a junior or senior. They’re still in the developmental stage. To curb that approach would unnecessarily change the ensuing preparatory phase to lighter intensities, which would re-shape the entire yearly plan, and not for the better.

Older Athletes. Older athletes, who have gained strength by aging, training, or experiencing the stressors of a few years of high-level competition, are not likely to maintain strength, power, and speed during the season.

Professional Athletes. For the most part, the professional athlete is developed physically for their sport. In other words, a player in the minor leagues who is a 5-6 home runs a year, 60 RBI guy is not getting called to the big leagues to develop into a 20-30 homer, 100+ RBI hitter. Doesn’t mean that they can’t improve in some physical aspect, but development is another thing. This affects the training and the outcomes.

By and large, underdeveloped athletes will not be at the professional level, certainly not in MLB. A high school or entry-level collegiate athlete should be expected and programmed to improve strength, power, and other physical expressions throughout the in-season workouts.

Off-Season MLB Training Program

It’s tough to talk about the in-season training program without giving some attention to the off-season or pre-season. The in-season program is set up by all the other training phases. Because discussing exercise selection involves great detail, I want to focus on the volume and intensity of the training–the sets and reps.

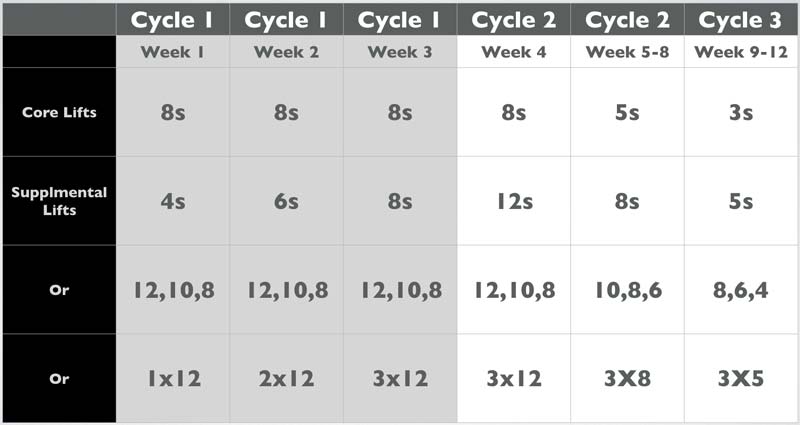

I know. If I was given this information, I might question the appropriateness of this program for a major league player. It’s pretty simple. This was the template in my first go-round with the Oakland Athletics from 1993-2001. I promise you, there was more detail and individualization–but not much.

Considering the challenges of the MLB strength and conditioning coach, one point deserves recognition: We are unable to supervise most winter workouts.

The off-season program philosophy started with this point. I wanted a solid, simple format that the players could understand and follow. I’m not sure I’d make it look too different today; in person, we can make adjustments in real time that we could never make at a distance. So simplicity would still have a major impact on training programs I could not supervise personally.

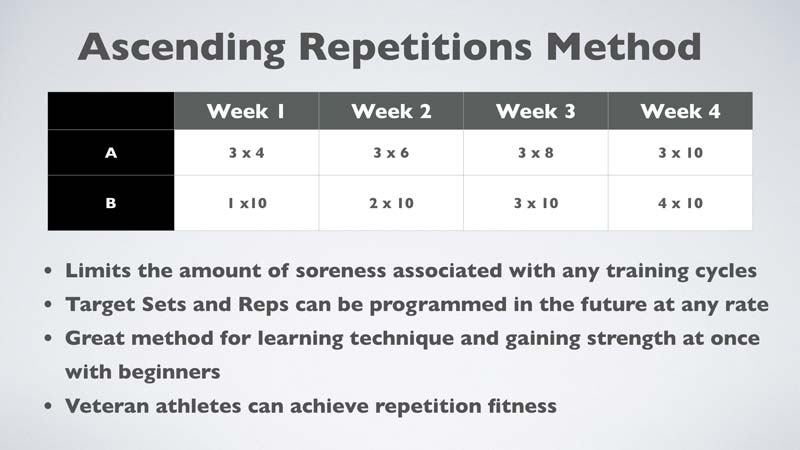

As you can see, the overwhelming theme was to add weight as the weeks went on while the repetitions decreased. It’s the simplest strategy for the overload theory. For supplementals, it depended on what stage of training the players were at. Those who needed a “slow cook” on the way to heavier weights began with my Ascending Repetition Program, which can also be performed with core lifts. It’s senseless and useless to start out anyone on a high-volume program early in the off-season–to get them so sore that painful effort would hinder the ensuing training and conditioning sessions.

Spring Season MLB Training Program

Pre-season, or spring training, was similar to Cycle III of the off-season with only one exception: At the beginning of spring training, we began with lighter than normal weight for the same rep range to account for the rapid increase of baseball related activity. My spring training plan had to consider the fittest player, the one who worked their butt off over the winter, and the player who did very little, who was not fit and expecting to follow the old paradigm of playing himself into shape.

How would I do that? Then it hit me. They needed the same program. It was a program that had the same base philosophy of low volume/low intensity building to low volume/high intensity in both conditioning and weight training.

Player Who Worked Their Butt Off. Cycles of hard work need to have recovery periods. It can’t be a linear load without a break (a decrease) in the training load if there is to be progress and training management. And this guy needs a break. The beginning of spring training is the perfect time for backing off the strength and conditioning in this case. Not stopping it. Backing off allows for:

- The everyday and somewhat immediate increase in baseball activity which otherwise would be too great of a physical overload.

- The difficulty, and against prevailing and conventional thought, of working both on raising or gaining physical capacities and improving sport skills.

- The avoidance of being sore and tired at the beginning of camp, which significantly hinders skill improvement and, in some instances, the chance of making the ball club.

- A better focus on the game, making it easier to concentrate solely on baseball.

Player Who Did Very Little. What can I say? It happens. Not as much as it used to because more baseball players have adopted better training habits. But it does happen and not always because of laziness. In the big leagues, you deal with adults. Adults with significant others, children, parents, illnesses (both family and their own) and other disruptions that life brings. No matter the reason, it does not do the player or the ball club any good when the player is too sore or too tired to play baseball because of a program that does not match their physical status.

In-Season MLB Training Program

Finally, we reach the basis for our story. Remember, when designing an in-season program, we want our athletes to stay as strong as possible while minimizing fatigue to reduce muscular soreness.

Force Production

Let’s tackle the strength issue first, particularly with the core lifts (squatting, pressing, and pulling from the ground). Strength is intensity-driven; it’s not a volume thing. The closer you get to one repetition, the bigger the strength effect. In this case, strength is defined as the highest possible expression of force; the most weight or resistance one can execute for one repetition.

Make no mistake, strength is a byproduct of any resistance training program. In other words, no matter what resistance you use within reason, at some point you should be able to do more repetitions or use more resistance than the amount you begin with.

In the real world, one only has to look at Olympic-style weightlifters whose programs hover around the 1-3 repetition range for most of the year. If you track the progress of any competitive lifter over time, you’ll appreciate the gains in strength.

As for the legendary myth that lifting heavy weights make you bigger, a fear that many baseball athletes and coaches have, just look at the weightlifters. Because they compete in weight divisions, they pay careful attention to their body weight. Some lifters remain in their division for years and continue to set personal records, sometimes world records, without gaining body weight. And they train in the 1-3 repetition range. End of story.

Any honest strength and conditioning expert who implements higher intensity training will tell you that the workouts at the beginning of the season are pretty accurate regarding training intensities; the loads for 85% for 5 reps or 2-3 reps at 90% are right on target for a true or predicted 1RM. They’ll also say that, as the season wears a player down, the accuracy of the percentages begins to skew. Some find this occurs at the season’s ¾ quarter mark.

For example, the load used for 85% might be actually 90% of the 1RM due to a decrease in absolute strength. Sure, you can estimate a new 1RM at this point. Instead, I shifted from the percentages to the load. We looked at the amount of weight the player could do for 5 reps as opposed to attempting 5 reps with 85% percent, which most likely would turn into 3-4 reps.

Although it satisfies my philosophy for heavier weight and fewer reps, working off heavier-than-prescribed loads at that point veers off my periodization schedule. Instead of the 85% workout, 3-4 reps becomes 87.5-92.5%. For me, going too heavy any time of the year is always a problem.

I also believe that in-season workouts that follow a low-volume, high-intensity program reduces the risk, severity, and incidence of injury. In baseball, the majority of game movement is immediate with maximum contraction, requiring the ATP-PC energy source. Weight training at 85% intensity and above teaches the muscles to instantly contract at maximum effort, conditioning them to this type of activity.

Think about it: When back squatting for a set of 8 reps, you’re not hitting max tension until about reps 6-7. Your energy–maximal exertion–isn’t available for the first rep or even the second or third. You’re warming up for the final reps.

Unfortunately, when the ball is hit in the hole between shortstop and 3rd base, the shortstop does not have the luxury of a few warm-up steps toward the ball before breaking at full speed. He needs to go now. The first rep at 85% or higher, if not at the liftoff, is a “go now” mindset. You’re not looking ahead to the third rep. Your total focus is on the first.

For this reason, low-volume, high-intensity weight training teaches muscles to immediately and intensely contract. This not only stimulates the best strength effect but, in baseball, it’s also resistance training’s best vehicle for injury management.

Low-volume/high-intensity weight training gets the best strength effects and best manages injuries. Share on XDo they lift heavy all the time? No, and no one should. Higher intensity load training blocks earn rest periods even though they might not be complete rest (days off). Lower intensity days enable the athlete to lift heavy when the time is right.

If you’re looking to maintain strength in-season, focus on gaining strength in-season.

End of Pre-Season. Peak for the start of the season. The last few pre-season cycles should be high intensity (85-100%) and low volume (1-3 reps) for pulls, bench presses, squats, etc. and 5-8 reps for supplemental lifts.

Beginning of In-Season. For the first few weeks in-season, drop intensity (50-70%) and maintain low volume (3-5 reps). Supplemental lifts will be at 50% volume or intensity. For example, a normal 80lb incline dumbbell press 4×12 would look like 40lb 4×12 or 80lb 2×12 or 80lb 4×6. In this way, the athlete can recover from an intense last few weeks leading up to the season, have a slight training recovery, and prepare for heavier lifting to come.

If you want to maintain strength in-season, focus on gaining strength in-season. Share on XIn-Season. Aside from recovery weeks every 3-4 weeks at 50-60% normal volume and or loads, stay with the strength zone intensities 85-100% with very low volume (1-5 reps) throughout the season.

Lifting Heavy In-Season Will Tire Players

If you wait for your players to feel fresh or rested to train during an MLB season, they will never train. You give up freshness now to have strength, power, and health later. If you do it right, there might be less recovery. From my experience with players who train heavy in-season, they know it’s the cost of doing business to finish the season with strong numbers or have big time showings in the playoffs. I’ve seen both of those scenarios come true.

“I’m too tired to get a good lift.” “I’ll lift the day after a day game so that I’ll have more energy.” Look, you’re not helping your athletes if the volume of training is too high–I’m talking about the difference between 5 and 8 reps, or 8 and 12 reps. This is a game that’s all about volume with traveling, stretching, warming up, hitting, throwing, and fielding nearly every day. Why would you want to add more volume? You don’t.

It reminds me of the 80’s and early 90’s when it was common to imitate the event or sport in the weight room. A bad idea now and a bad idea then, but it made sense to us. Distance runners would weight train in repetition ranges of 12-20, a huge mistake that still occurs today.

Since baseball has so much volume, the sport needs anti-volume. From my experience, I’ve learned:

- Too much volume adds fatigue to fatigue.

- If you want a player to add muscle, therefore raising the volume, you must wait until after the season.

- Higher volume with sub-max loads is a waste of time. Athletes can’t acquire strength with light loads nor hypertrophy at sub-max loads at high volumes.

- With no volume, there is no soreness.

- A “de-load” week of light weight and high repetitions is not a rest week strategy.

- More repetitions and sets mean spending more time in the weight room. At 10:30 pm, more time in the weight room was the last thing we needed.

Having higher volumes without hypertrophy as a goal and using submaximal loads for these rep ranges will add volume on top of volume with no appreciative benefit and one big adverse effect–fatigue. Again, if you’re not working on size and you’re not working on strength, what are you doing?

Note: Starting pitchers trained before the games, both conditioning and weight training. Relievers had the choice of before or after the game, depending on whether they were available to pitch that day. The program for infielders and outfielders was divided by body part per day; back, legs, chest, arms, and shoulders were each performed only once per week. Some would combine body parts to shorten the frequency to less than five days per week. Training time for the five-day program was 10-20 minutes maximum-intense and dense.

Dwight Daub, a very close and dear friend for more than 30 years and the former Head Strength and Conditioning Coach of the Oklahoma Thunder gave me one of the best pieces of advice when it came to athlete tracking. “All the tracking stuff is fantastic; we like it. But, you know what we found out? When we tracked minutes doing stuff–treatment, lifting, practicing, games, shooting practice, walking at the mall, shopping, playing with the kids–we found the guys who had the most minutes were the most fatigued.”

The game itself has enough volume during the season, to say nothing of everyday life. Share on XA great, simple lesson on in-season training. Even though Dwight was profiling professional players, you can still see activities that all athletes participate in. Watch the amount of “stuff” your athletes are doing. Specifically, in-season strength training. The game itself–whatever game–has enough volume during the season, to say nothing of everyday life. While the science leans toward the idea that lower volumes decrease training-related fatigue, common sense also says that we have to account for more than the training and the games.

Soreness: High vs. Low Volume

I might be a bit Draconian here, but I’ll say it anyway. Volume is the killer of all that is good. Speed, speed-endurance, strength, and power are a few qualities that are nearly impossible to find during higher volumes of training. And trying to create these qualities with high volume becomes a Sisyphean effort. Volume dulls performance, plain and simple. There are times when volume training is effective, and we expect and plan for some dulling but never before a needed performance.

One of the lost byproducts of high repetition training is muscular soreness. We don’t want the clubhouse buzz to say that Joe was sore yesterday and had a bad day at the plate. All of a sudden, players whose lives depend on good days at the plate, may skip a workout or worse, lose trust in your program. Guys who train hard expect to be a little sore now and then but not sore enough to be a problem, perceived or otherwise.

One of the lost byproducts of high repetition training is muscular soreness. Share on XTwenty years ago, Orel Hershiser of Los Angeles Dodger fame, who was with the Cleveland Indians at the time, told me, “You know why pitchers get sore from lifting? Because they don’t lift hard enough!” A kind of reverse Zen statement; I was the grasshopper. He meant that, if you go hard every time, you get into lifting shape and the soreness ceases. At least enough to allow a pitcher to pitch in a big league game. Here’s the story though, it’s hardly ever the amount of weight that makes you sore. It’s how many times you do it.

Think about some max lifts you’ve done with 1-3 reps with no more than a total of 9 reps over 3-5 sets. Not much soreness, even with a 1RM. Now think of any exercise you’ve performed 3-5 sets of 8-12 reps with and remember how you felt the next day or the next two days. I’m not saying it’s a bad feeling. That swell and tightness is our goal sometimes. But not before a major league baseball game with the world’s best players.

As for the muscle bound syndrome and the choice to use light weights and higher reps to steer clear of being tight, I put a challenge up to some players. I told them to do dumbbell curls with a weight that only allowed for a max set of 12 curls on their throwing arm and then immediately try to throw a ball. Good luck.

It looked pretty bad, and the athletes mentioned the words pumped and tight. When I asked them to do one rep at a max weight then throw the ball, they had a much better feeling and more accuracy. That’s when I explained that they just experienced an example of high and low reps, light and heavy weight and what it felt like in short display.

High-intensity work limits soreness, emphasizes strength and defeats fatigue. Share on XSoreness is usually a function of too many repetitions per set or workout. Heavy weight hardly ever causes muscular soreness because the load is too heavy for repetitive movements. It’s the repetitive movement that causes many perturbations in the muscle and surrounding tissues, leading to soreness. Now we have yet another virtue of higher intensity/lower volume work: limiting or eliminating training soreness in addition to emphasizing strength and defeating fatigue.

Common Sense + Intuition + Science = The Best Results

It’s a little of everything, isn’t it?

Common Sense. It’s a bunch more than you think and it’s based on science. A coach wants his athlete strong at the end of the year especially if the playoffs are involved. To achieve this, the program has to have an effective progression–not too much and not too little–that includes not tiring the athlete or making him sore yet intense enough to create strength. At the same time, we don’t want to affect performance so that the playoffs are only a wish.

Intuition. It’s not magic. Intuition comes from experience. Intuition is your personal data base being quickly assessed into probabilities. Intuitively, a coach realizes the rigors of an MLB season–the lifting, the travel, family and friendship stress, performance, pennant race, the next contract, a clubhouse of various personalities–and bets the physical and mental fatigue that accompany the game will take a toll on the player. The next question is: How do we keep the player physically and mentally healthy while keeping his performance at peak? The answer is to work hard enough to stress the body but to not apply so much stress to negatively affect performance. And add just enough adjustments to make it all come together.

Science. Strength and movement physiology, baseball kinesiology, fatigue research, and the effects on performance and injury are clear.

Other Sports

The equation above applies to other sports as well, much like the in-season philosophy I’ve outlined here: The lowest volumes and highest intensities (loads) possible throughout the season for retaining the most power and strength while holding the best resistance strategy for injury management.

My first sport at UCLA as the head strength and conditioning coach was rowing in 1984. I immediately found out how many strokes in 2000m a boat would take (skull to 8s) to set a repetition range or at least the total repetitions in a set. So there I was, trying to configure a workout that had 200+ reps for one set (simulating the estimated number of strokes for an 8) or dividing 200+ reps among 3-4 sets per exercise.

If you know anything about crew, you know how absurd it was to program those kinds of repetitions and sets. Certainly a repetition range and volume that high has no relation to what defines strength. And while the repetition ranges would affect strength very little, we now know there will likely be a hypertrophic effect. Gaining weight, albeit muscular, is an issue that no boat needs.

Also, aside from never being able to mimic sport through weight training, I was not subscribing to a basic tenet of strength and conditioning–programming by need. A knee jerk and shallow hypothesis would be that, if rowers take that many strokes in competition, they need that in the weight room.

A scientific approach would lead one to say rowers have plenty of volume with rowing-specific work, by well, rowing. So they don’t need volume. What do they need? They need anti-volume. This is the very same hypothesis and the reality that distance runners (distance runners coaches) need as soon as they ditch some of the common, very old strength training theories that have not been supported anywhere.

It’s important to note that the length of the season dictates “how many up and how many down” will fit into a scheme and the overload progression for a season, which starts at the lower end of the 85-100% intensity range.

Season length dictates how to alternate high- with low-intensity for overload progression. Share on XWhen I coached basketball in the ACC, the season was only about 17 weeks long. I did not consider the ACC Tournament as part of the in-season because it was the beginning of a new season. So it was easy for me to safely program 90% or higher 3-4 times during the 17 weeks. Other variables were part of the equation as well that made it sensible–the age of the players, the year-round supervision, plenty of testing and assessments, and no outside interference.

There was no way, however, that I was coming out of the gate in MLB with 90% in the first 4-5 weeks in April with 5 months to go. When we hit 5s in the first two months, they were hard 5s.

Certainly, there are times when 100% effort is asked of loads that can only be performed 1-3 times. But, in the end, low repetition ranges and heavier weights in-season work best for every sport.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

Very insightful read. Thank you!

Awesome

What a great article! So much detail and information! Good job!

very good info here. However no mentioning of grip strength. Training for grip strength , strategy and importance.

Hi Bob,

This is a very good article. Low reps at a high percent of 1rm seem to instill fear and trepidation in many folks. They think they’ll get musclebound, sore, slow and so on. The opposite is true.

One think you say the sorness comes from high volume. I’d add that it does, but it’s real cause is the eccentric portion of the contraction. High volume obviously has more eccentric contractions than low.

Olympic lifters don’t even do the concentric portion of many of the lifts they practice.

You don’t necessarily want players doing Olympic lifts, but it would be interesting to try some lifting that removed the eccentric portion of the contraction and observe if one could then do more volume without soreness or if one would feel even less fatigue. I digress.

Thanks for the well written article.

Weightlifters remove the ECCENTRIC PORTION, NOT CONCENTRIC. cheers

Great article coach

Great article! How many days per week for the in-season training? Is that daily? My twin boys play basketball and baseball, essentially a year round sports schedule. Until I read this, I thought there was rarely a way to fit in a weight training routine. There is practice or game almost everyday.

I am not clear though on frequency, for example, are squats (1 to 3 reps) done daily?

Great article and well said Coach

Have believed this my whole life

Who ever wanted to be the same or weaker and the end of the season?