This article is part of a series in which I outline the athlete level classification program, also known as “blocking,” that we use at York Comprehensive High School (YCHS). It’s imperative for sports performance coaches to have a well-planned, evidence-based program to progress young athletes through as they grow. Just as a teacher in an academic class would build on concepts and practices, so must we.

In this article, I expand on how we prepare our rising freshmen as they move through our “Block 1 New” classification and eventually graduate to “Block 2 Novice.” I outline the programming and technique protocols we use with our Block 2s in depth. Finally, I discuss how our athletes prepare for graduation from Block 2 and into our “Block 3 Advanced” category.

I hope this article will be of help to you and your athletes. We work in a field where taking other coaches’ ideas and adjusting them to your own program needs is a very powerful skill to possess. If this or anything else I have will be helpful to you, I urge you to copy, adjust, and make use of it in any way possible.

Review of Transitioning Block 1 Freshmen to Block 2 Sophomores

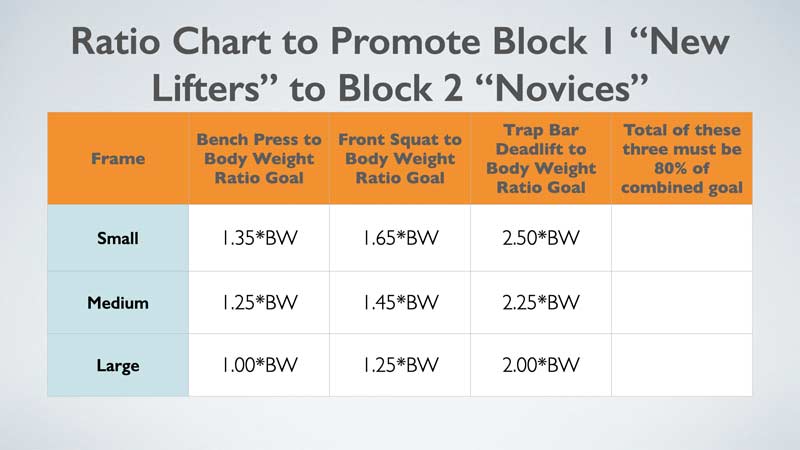

In my previous article on introducing new athletes to our program, I discussed the “slow cooking” process of transitioning our incoming freshmen from our Block 0 program to our freshman Block 1 level and touched on the Block 1 “graduation” standards. In general, the process stays consistent as we progress up the ladder of our program’s layered programming model. We use a combination of movement mastery, body frame, body weight, and strength ratios in our three strength movements to recommend promotion. Our Block 1s must achieve a combined 80% of the following “goals” to be eligible for promotion to Block 2.

Figure 2 shows an example of this using the chart of a large-framed athlete with a body weight of 200.

This athlete is well above the 80% threshold. If he also masters his movement, he will be promoted to Block 2. These numbers will be projected 1 rep max totals. In general (there have been individual exceptions), we do not 1 rep max test our athletes until the end of Block 2 (sophomore) in preparation for transition to Block 3. We project these off a “plus” set that we do at approximately 86% of their previously predicted 1RM, which we do for each of the three strength movements once in each four-week cycle (to be discussed later in the article).

Once our athletes reach these standards, we graduate them to Block 2 Novice and adjust the programming to reflect the progression. At this point, we also introduce our athletes to our devices. Part of earning promotion to Novice is being given the privilege of going from a paper sheet with a workout on it to the use of CoachMePlus on a tablet. This is a step toward the gradual move from coach control to a student-athlete controlled learning model.

Review of Block 1 Programming

In the previous article, I discussed how we use a modified version of progression for our three main strength movements that is very similar to Jim Wendler’s 5/3/1, or a traditional BFS program with some slight modifications for our Block 1 athletes. As with all parts of our program, athletes must earn this in a progressive manner. Initially (starting in the summer of freshman year), we spend time reviewing and reteaching all movements from Block 0. We slowly progress throughout the summer, adding variation until we feel the group is ready for the next step.

Step 2 of our progressive program introduces our athletes to the general outline of how they will do things on a daily basis during their time with us. We put the workout in the form of our modified tier system, using the movements that they will learn and use throughout their time in Block 2. We print these as sheets from our CoachMePlus calendar.

During this period, the load is set and does not change until they have sufficient mastery of each movement and we are ready to add weight to the movements. Not all of our athletes will graduate at the same time. We do our best to promote only when each athlete is physically prepared to do so. The set load is kept very light. This can sometimes frustrate athletes who may be capable of lifting more weight than programmed. You must explain to the group why you program the way you do and the advantage they will have when you finally do add to the load.

During Block 2, our goal is mastery of movement, and the weight used doesn’t really matter to us at this point except as a teaching tool, says @YorkStrength17. Share on XThis is also an excellent opportunity for our athletes to master technique and practice bar speed. We always have a few athletes who, even with the very light load, struggle with it being too much. We instruct those athletes to stop at whatever weight they can do without a struggle and use the same weight for the rest of the programmed sets. Our goal is mastery of movement, and the weight used doesn’t really matter to us at this point except as a teaching tool.

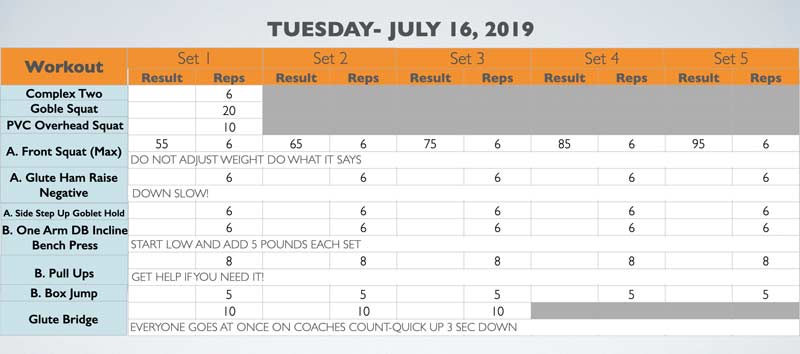

Here is an example of a printout given to the Block 1 athletes during the last few weeks of summer.

The final step of Block 1 is to progress to using percentage of projected max, as well as volume periodization, which they will use through the end of Block 2. This programming starts out initially with a very modest projected max for our bench press, hex bar deadlift, and front squat movements. It also features progressing variations of vertical and horizontal push and pull movements, Olympic variations, and posterior chain variations, as well as squat variations other than the front squat. The vast majority of those reps will be done initially in the 50-59% relative intensity range to focus on movement mastery and bar speed.

We progress from that point with both main movement projected max and relative intensity of all other movements and variations. By the end of Block 1, our athletes will have progressed to the point where we have a pretty good idea of a predicted 1RM for our three main movements based on the plus sets they do once in each cycle. Those plus sets in Block 1 set the projected 1RM, along with technique proficiency, and we use them to determine when an athlete is eligible for promotion to Block 2. By the late winter and early spring, we usually have a handful of freshmen ready for Block 2.

Programming for Block 2 Athletes: Basic Design Layout

Our program for all layers is a three-day-a-week split. We use a modified tier system with the traditional total, upper, and lower daily split that rotates once per week through speed/dynamic Tier 1, total strength Tier 2, and volume acclimation Tier 3. Tier 1 includes Olympic movements and variations along with other lower-intensity/higher-velocity movements. Tier 2 features one of our three base strength movements or a variation (trap bar deadlift, squat, and bench press), an antagonist auxiliary movement, and a prehab/mobility movement.

Tier 3 is where one area of our “modified” version really comes into play. Traditionally, this is a volume/hypertrophy tier. We use this much of the time for that same programming. However, this is also a place where we work in some additional Olympic squat and/or pull variations as dictated by our volume progression plan, which I will discuss later.

Our yearly plan is split into four-week cycles. We use a concurrent periodization plan and train equally for power, strength, and hypertrophy together. What may be different from some programs is that our method of progression uses volume as our priority method of overload. Intensity is a secondary factor and is not necessarily tied into volume—both can be manipulated independently as needed.

Therefore, when I say “heavy” or “light” day or week when describing a microcycle or day within a microcycle, that does not refer to the intensity range of our lifts. In fact, it refers to the total volume count for reps 50% or over in one of our six “counting” movement families (squat, press, pull, clean, snatch, posterior chain). Our heavy days may indeed use lower-intensity ranges and our light days often include heavier intensity.

Why we do this is an article in itself (or a book called “The System,” which is one of the most influential books I’ve ever read). Basically, we do this because we place great value on movement proficiency and bar speed over absolute strength. We must always remember the actual sport we are preparing for is the priority, not the number we can hang on a goal board.

Moving a bar loaded so much that they move it very slowly (and do it often) will make an athlete stronger. However, the strength they gain from that will likely not translate to sport as well as a little more moderate load moving at max velocity. Bar speed is the king of transfer to sport from the weight room. We believe using volume as our primary form of forcing adaptation via overload is the most effective way to produce our desired outcome for our athletes.

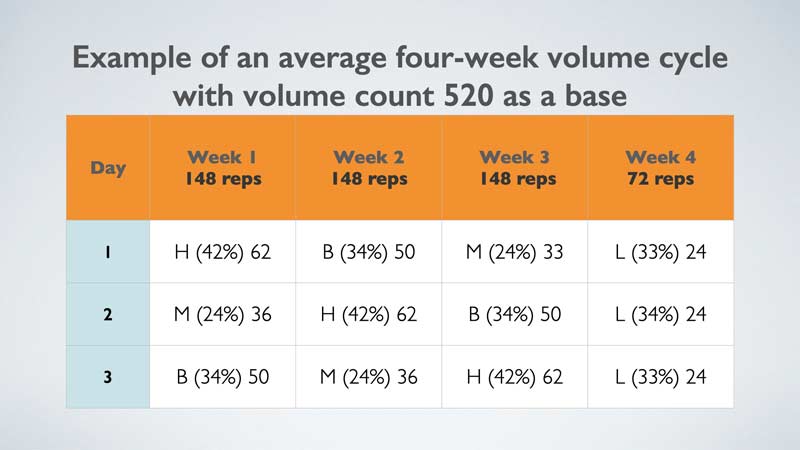

We believe using volume as our primary form of forcing adaptation via overload is the most effective way to produce our desired outcome for athletes, says @YorkStrength17. Share on XAs in all aspects of our layered block program, we transition from a more consistent set-rep scheme to our volume wave periodization in steps. In Block 2, our athletes use the wave volume program in all movements except our Tier 2 base movement. We continue to use the version of “5/3/1” we began using at the end of Block 1. Block 2 athletes use a wave within the days of the week, but the total reps stay consistent except for the volume deload during the fourth week.

In blocks 3 and 4, we further “wave” the volume within each week of a cycle. This is another way we use volume to ensure the athlete continues to progress and avoids training plateaus as they age in our program. We also do not use “snatch” variations until closer to the end of the block, so those are not reflected in the volume count at this point.

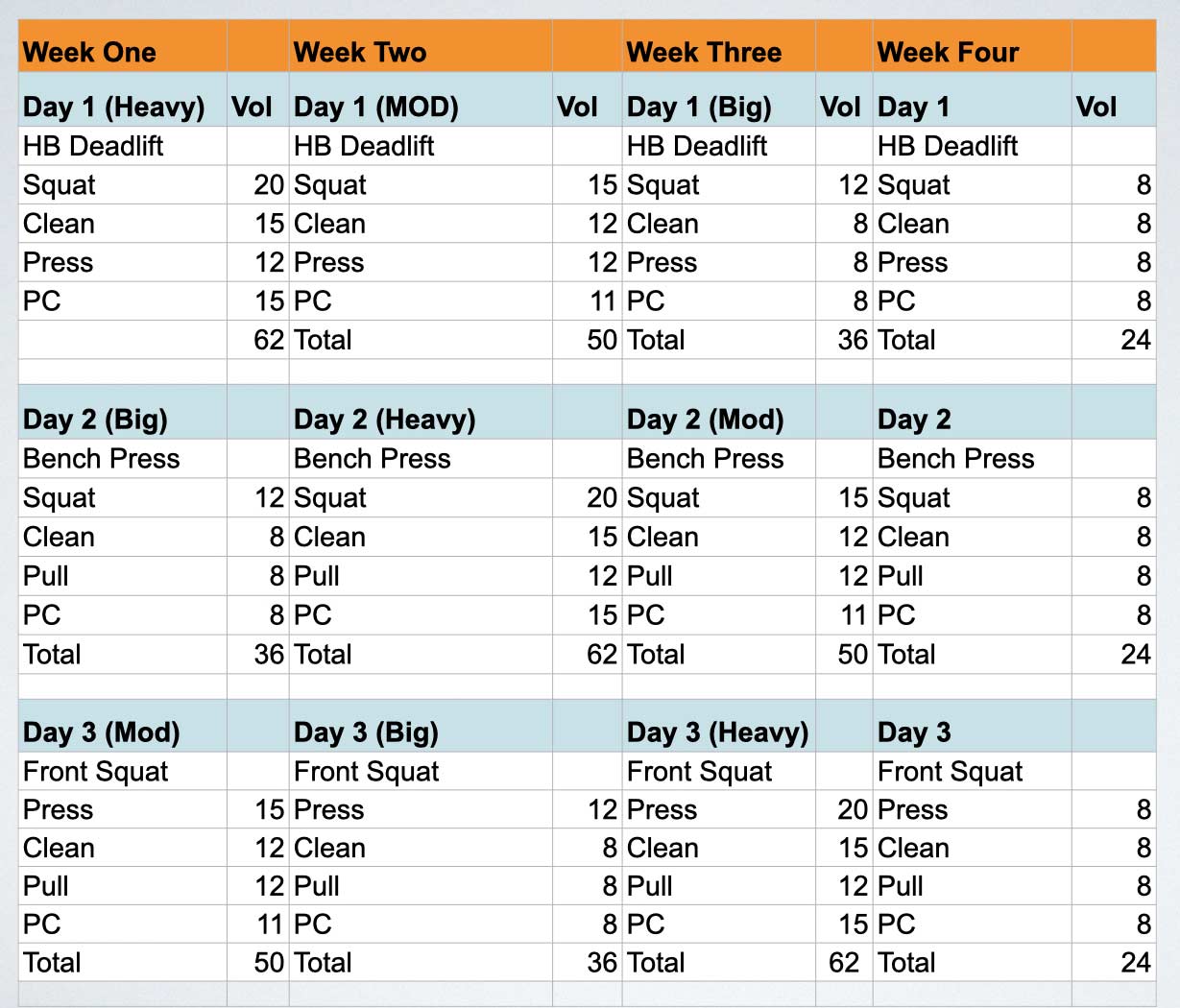

Our four-week mesocycle is divided into three-day weekly microcycles. The total volume for each cycle is based on the goal number (850-875 counting reps per month) we want our elite athletes to reach by the last few cycles before their preseason. We then work back, subtracting +/-10% per cycle (with a regression cycle at the start of each new block) until we reach a number our Block 2 athletes will actually start with (520 in Cycle 1). Within the week, each day is also subdivided as shown in figure 4.

During this time, we keep the intensity ranges low, spending most of our time in the 50-69% range with all base strength movements. We increase the intensity slowly and cap our relative intensity for each individual movement at 2% per four-week cycle.

Figure 5 below shows a week. Remember, we only count reps over 50%, so even if it says “8 reps” we may do 12, but four of them would be below 50% intensity.

Strength movement programming is the final component for our Block 2 athletes. Our Novice athletes use a less complex version of programming for our “Big 3” Tier 2 base movements (TBDL, front squat, and bench press for this layer). As stated above, this is a version of Wendler’s “5/3/1” program that I adapted from a good friend, Jeremy Evans. We really embrace the idea of simple to complex in our slow-cooking process.

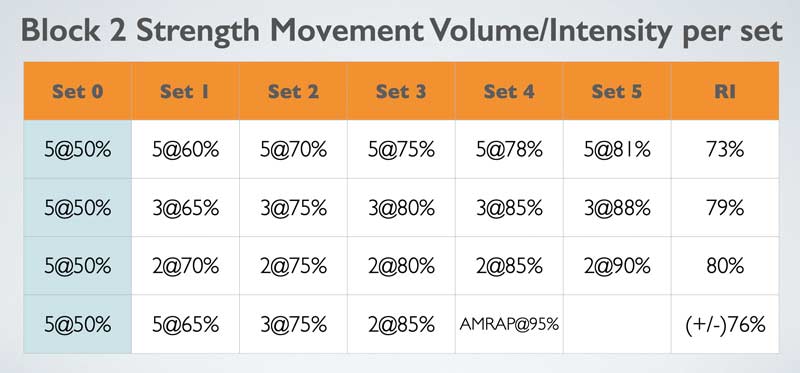

I feel that jumping “full go” into our volume periodization program with sophomores may cause some confusion. Therefore, we allow them to use the following program (figure 6) for their main lifts while we acclimate them to the increasing volume. Our athletes should have technique proficiency with these three movements by this point, and we feel comfortable adding intensity to them.

Our goal is to eventually have the vast majority of our Block 3 and 4 athletes’ reps coming in at the “sweet spot” of 70-85% for bar speed/strength, says @YorkStrength17. Share on XWhile we keep the majority of our reps in the 50-69% range and build from there, this program provides an opportunity for our athletes to experience a higher load with less volume. As in the “5/3/1” program, we set a training max of 90% of predicted 1RM. Therefore, when you see a set at 95%, it is actually a set at around 85%. Our goal is to eventually have the vast majority of our Block 3 and 4 athletes’ reps coming in at the “sweet spot” of 70-85% for bar speed/strength. This is their first step toward that goal.

Our program has four separate volume intensity ranges. Our athletes do one each of the three training days in a week. On Day 1 of the next week, we do the fourth and then start over. This ensures we get one “dose” of each range with each of our base movements. Using the AMRAP set, we can get an approximate adjusted max each cycle for each movement as well.

It’s very important to keep in mind that just because an athlete graduates to Block 2, doesn’t mean any of these programming items are set in stone. The “coach’s eye” is still the best tool to give our athletes what they need. Too many times, coaches get caught up in rushing athletes to heavier loads and more complexity of movements.

There is no need to do that. Just about anything we do for them at this age will result in growth. I see no need to push any of our athletes to missed reps or failure, especially our Block 2s. Make sure you have a progression and regression program and use it. The vast majority of our Block 2s do not rack cleans or do back squats. When they are ready, they will do them.

Just about anything we do for them at this age will result in growth. I see no need to push any of our athletes to missed reps or failure, explains @YorkStrength17. Share on XFrom a safety and a sports performance standpoint, a loaded jump or a quick and soundly executed clean pull are superior to a “reverse curl”-looking hang clean. Remember SPORT first, numbers second. A clean doesn’t translate to the field of play if it’s done with poor technique. Neither does a slow, overloaded or “half” range back squat.

Our job isn’t to make athletes the strongest people on the field or court; it’s to help them reach maximum performance. Mastery of movements and being able to do those movements at max velocity BEFORE heavy loads are added will help athletes stay healthier and be more explosive during their sport. Adding load and more movement complexity slowly as they master bar speed can make that explosion very powerful as well.

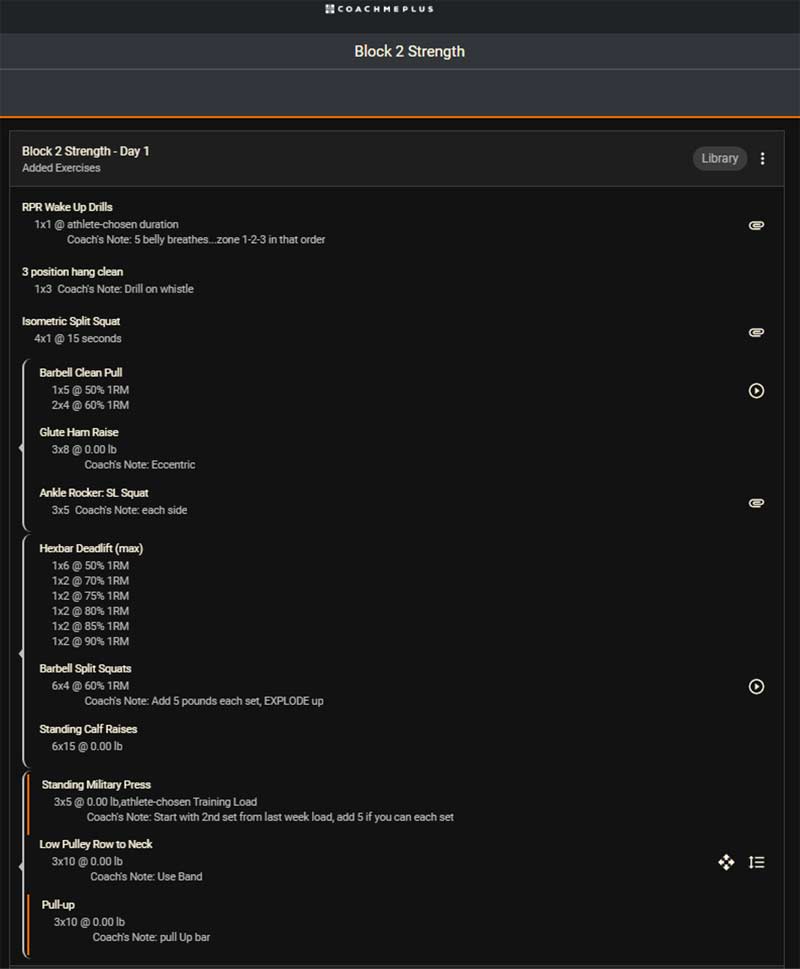

Here is a typical workout from CoachMePlus for our Block 2 group.

Tier 1

Tier 2

Tier 3

Block 2 Final Notes

The program design above is what our athletes use as we move through Block 2. Generally, we see a small handful of athletes begin to transition to Block 3 during the mid-spring of their sophomore year. Most, especially my football athletes (who have classes year-round), graduate after our May testing.

As I said above, this is also the time when a few athletes also begin the transition from pulls and loaded jumps to hang cleans, and from front squats to back squats. I do not allow an athlete to do hang cleans if they “short pull.” That is the No. 1 mistake my athletes make. The second is foot displacement being way too wide during the catch. Both of these errors take away from the power development of the movement. I’d rather they do a loaded jump for four years than a poorly executed clean.

With squats, we look for a solid position and mobility to gain proper depth. If they can’t do a proficient back squat, why not just keep them doing a great front squat? Again, I have to say SPORT first, lifting second. Use movements and variations that develop the athlete and transfer to sport, not just some that sound good to say you have them doing but can’t be done efficiently.

Use movements and variations that develop the athlete and transfer to sport, not just some that sound good to say you have them doing but can’t be done efficiently. Share on XIn my next article on this topic, I will write about the transition from Block 2 Novice to Block 3 Advanced and Block 4 Elite. I will begin that article discussing the body weight goals and technical expectations that must be reached to qualify for graduation to those levels. I will also get further into our volume periodization programming and how we take our athletes fully into that program during blocks 3 and 4. I hope you can take what we have had success with and integrate it into your program.

If you have not read the book, “The System,” I urge you to do so. One of the authors, the great NFL strength coaching legend Johnny Parker, told me that once I used this type of programming, I would never go back. He was 100% correct. We are two years into it, and it gets better every cycle.

We have used that model as the top end of our programming. It’s what we use for our advanced and elite groups. We then reverse engineered it to peel off layers of complexity and depth, and come up with solid layered progressions that allow us to “slow cook” our athletes and fully prepare them as individuals for the rigors of high school athletics.

My hope is that if you do not already do this with your program, this will inspire you to do so. Even if you don’t do it the same way we do at YCHS, the framework is consistent and allows you to research and develop your own plan for layering your sports performance program. As always, please feel free to reach out to me with any questions or comments.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF