[mashshare]

The squat has become a contentious issue of late, and the questioning of its applicability has been explored extensively across this website, including these two must-reads by Carl Valle and Bryan Mann.

Squatting is an important athletic development tool and it should absolutely be trained in conjunction with unilateral work. This is not an either/or scenario, but an optimization through intentionally programming the concurrent or sequential application of both. The back squat can often stymie athletes and coaches coming to it late in the game, especially if steps were skipped during development phases for the athlete.

If you are after extensive guides on the anatomy and physics of the barbell back squat, I’d suggest going to read other articles on SimpliFaster or Greg Nuckols’ über guide on squatting. This article will focus on applied coaching challenges and how to overcome them.

Let’s get the squat depth talk out of the way first. Squat depth has been shown to have a significant effect on muscular development at the hip and knee joints, particularly with respect to the glutes. For instance, with on-the-road squatting, working with a population of traveling athletes means variance in the availability of equipment, so having the door knob squat or solid bodyweight squat as options opens up a world of possibility and consistency.

The key takeaway here is that movement quality drives loading strategy and not the other way around, says @WSWayland. Share on XThe key takeaway in this article is that movement quality drives loading strategy and not the other way around. This may require “going back to school” for some athletes, but the longer-term payoff is worth the investment of time, even if this means mastering the bodyweight squat for a short period of time before moving on to loaded variations. To quote Carl Valle, “Barbell squatting is relevant, so if you can do it right then continue using this king of exercises.”

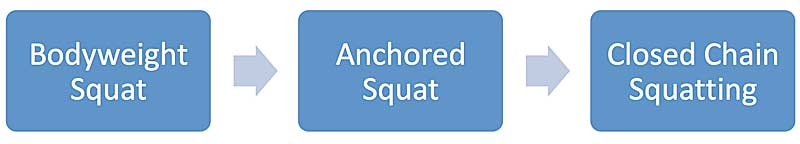

Having a rough plan for progression is a fundamental key to getting an athlete up to that clean, desirable back squat. I’ve seen instances of athletes rushed from a respectable bodyweight squat to a mediocre partial squat in a matter of weeks, primarily for the sense of progression, but also to feed the coach’s (and possibly the athlete’s) ego.

The Bodyweight Squat

The bodyweight squat is an absolutely overlooked exercise on the path to achieving a squat. You will occasionally come across athletes who can’t achieve this otherwise simple ask. The propensity is to progress people straight to a goblet squat or to entirely skip any sort of unloaded skill work and jump straight to a barbell squat. This is where the quarter squat phenomenon (to be covered later) in otherwise active trainees/athletes comes from. Coaches often talk about the necessity of bodyweight basics, but overlook this entirely to chase barbell numbers.

The bodyweight squat is an absolutely overlooked exercise on the path to achieving a squat, says @WSWayland. Share on XThis inability to perform a simple bodyweight squat is often seen in outsized athletes dealing with big body weights or leverages that rob them of stability. This is also a skill I find lacking when we run new intakes of youth athletes; the inability to bodyweight squat often rides along with an inability to perform other simple bodyweight skills. The simple act of proper generation of tension in the upper extremities can often alleviate perceptive instability.

Video 1. Simple mobility exercises that teach posture are foundational to squatting with a great pattern. Bodyweight movements are about teaching control, so make sure the athletes value them and don’t rush to add load to a bar.

Things like reaching have positive and negatives outcomes, as reaching helps provide counterbalance but can lead to excessive torso lean. Crossing the arms in a faux front squat can also be useful, but what I’ve found more useful is a position akin to a volleyball spike held at shoulder height and then focused on screwing the elbows downward, switching on the pecs and lats. Another novel strategy is having an athlete tightly hug themselves or something else, like a foam roller or med ball.

These are all strategies that require adjustments, then retests, and then further adjustments. Further progression can come in the form of simply loading the bodyweight squat with a vest or chains or both, and it’s entirely possible to make solid progress using this approach with very large athletes.

Anchored Squat

There is a subset of squatting that really doesn’t get the recognition it deserves as the squats aren’t considered true strength lifts in any meaningful sense. I’m calling this class of movement “anchored squatting,” but I’m probably not the first to think of this. By anchored, I’m suggesting that a single point—either the lifter or the load lifted—is in contact with anything external to the closed chain squat pattern.

The anchored squat ranges from door knob to band-supported to hand-supported safety bar squatting or supported belt squatting. The commonality is this: Giving an anchor eliminates the primary block to the full squat, which is compensatory shutdown due to perceived or real loss of stability. The doorknob squat is generally a great starting point for the absolute novice or the squatting-averse. By allowing a backward weight shift and a tall torso, it encourages the athlete to sit deeper into their squat.

The doorknob squat is generally a great starting point for the absolute novice or the squatting-averse, says @WSWayland. Share on XThis can then be progressed a number of ways, introducing the suspension squat using rings or a suspension trainer. Both these movements allow for backward weight shift. More-advanced anchored exercises mitigate forward weight shift, which is a limiter to stability once the athlete becomes more confident with their squat pattern. Movements like landmine squats and hand-supported squats place support anteriorly, but that is about as far as the similarities go.

Landmine squats are often touted as a useful squat alternative, and they are, to a point. The positioning of the landmine means the athlete can lean into the movement but still be challenged from a lateral stability standpoint, as the landmine arm still has a large degree of movement. It does come with one drawback: It can’t be loaded in a meaningful manner (much like the goblet squat). But it does make a good option when stuck in a gym with no rack or means of doing a moderately loaded squat variation.

Video 2. Healthy athletes can benefit from a heavy dose of anchored squat patterns. Some coaches add breathing elements or other skills, but make sure the movement is done properly.

The hand-supported squat or the Hatfield squat is a full circle of sorts: squatting with a safety bar and holding on to the rig, handles, or a bar set in the rack. This then allows the athlete to overload an already well-established squat pattern by taking out the limiting factor of anterior stability. It’s not uncommon to see athletes using 25% or more on top of their conventional back squat. I’ve increasingly seen it used as crutch to get athletes under a bar at the expense of good-quality movement; this is often demonstrated by dramatic hip shift, overuse of the arms, and a collapsed position.

Anchored squatting sits on a spectrum of options, but is always inherently inferior to traditional closed chain squatting. This is why this type of squatting can be used as a learning tool and discarded when viable; as an accessory movement to target specific facets of the squat pattern; and/or at its extreme, a means of novelty/stress reduction while maintaining a squat pattern in a training program.

Back Squatting in a Meaningful Fashion

The path to better back squats often lies in achieving a better front-loaded squat. Anterior loading acts as great way of achieving a smooth squat pattern. This can start with doorknob squats, move to plate-loaded front squats, progress to goblet squats, Zercher squats, and finally front and then back squats. This is because resisting anterior load is easier than trying to resist axial load for the uninitiated.

Scott Thom, writing for Just Fly Sports, said: “Why front squat first? The front squat:

- Forces you to keep your elbows up and pointed straight ahead, teaching you what it feels like to keep a big chest and maintain vertical posture through ROM of squat.

- Teaches you how to push your knees out and point your toes in the same direction as your knees. Thus, helping you to understand what it feels like to open up your hips.

- Forces you to sit back, or your heels will come off the ground. Helping you feel what it means to have your weight balanced. If your weight is too far back and you’re not clawing your big toe into the ground you will feel off-balance.”

The front squat is preferred as a starting point for the back squat because it encourages a movement-strategy-first approach. I can always spot the athletes who have spent time front squatting versus those who have not just from looking at their back squat. The athlete who has not taken these steps will approach squatting with trepidation and, at worst, turn every back squat into a partial one.

The front squat is a preferred starting point for the back squat because it encourages a movement-strategy-first approach, says @WSWayland. Share on XNotice that I make no mention of wall squats and/or overhead squats as progressions. Wall squats are often ugly movements that wind up with an athlete having to reach, but also lean, excessively anteriorly to achieve a good squat position. This is the same reason the overhead squat gets no mention, as it primarily becomes a shoulder/t-spine mobility challenge, which is outside the scope of this article. Overhead squats are often a display of mobility rather than a means to improve it or load the lower body in any meaningful fashion. The overhead squat must be earned, and in my experience, it has limited meaningful transfer. It’s an impressive display of strength, but that’s all it is—largely a display.

Video 3. Eccentrics are not just for stressing the body, but also challenging the brain. Heavy eccentrics provide major benefits to athletes by challenging upper centers of coordination while also training the general nervous system.

The partial squat is often the calling card of an athlete who has missed out on much of the aforementioned preparation. Partial squatting is often a subconscious compensation for unfamiliar joint positions and, importantly, a loss of balance. We know the benefits of loaded partial squats, but the majority of people perform them as a protective strategy rather than a performance-oriented one.

Idiosyncrasies are the common explanation of the partial squat apologists. But it is easy to differentiate an athlete who is comfortable in the squat at any depth from an athlete who lacks confidence, which is usually denoted by an inability to harness any sort of rapid eccentric action and a slowing tacking to a depth they feel is deep enough. Thus, the subsequent concentric phase is usually ropey as a result. This is often a case of loading strategy driving movement quality, rather than movement quality driving loading. I’ll explore this idea with two further examples.

Pragmatic coaches like Alan Bishop make extensive use of squat wedges. Cry and moan about it being a crutch all you want—it works well in populations typified by ankle stiffness limitations such as basketball.

Squat Progression

– Movement quality drives loading strategy

– Range > LoadSquat Low, Jump High

⬇️⬇️ 30 days of training ⬇️⬇️ pic.twitter.com/hUmDArVroF— Alan Bishop (@CoachAlanBishop) February 13, 2019

The squat wedge ostensibly acts to artificially lengthen the Achilles tendon and reduce “excessive forward trunk flexion.” Much like the thinking behind weightlifting shoes, this allows for forward knee translation and greater knee flexion. This isn’t the crutch some think it is as it patterns good movement. The wedge can be employed in various fashions: I’ve seen athletes who can squat perfectly well with bodyweight without a wedge, then as soon as they are loaded, compensatory shutdown for whatever reason stops them from achieving meaningful depth.

The introduction of the wedge allows for a positive flow to training. This is an example of movement quality preceding loading, even if that movement quality is assisted in a sense. Because athletes have greater movement availability, they can practice using it, which will further grease movement capability. Contrast this, however, to the “fix” below, which often causes more problems than it fixes.

The bench/box squat is an example of an approach that is a crutch that can pattern bad movement. Divorced from the powerlifting or accelerative strength context (usually for those who can full squat or a return-from-injury case), this often becomes a recipe for problems. The thinking is sound: Lower the height of the box/bench until the athlete can perform the movement with a full squat. However, this doesn’t ever seem to play out as progression strategy. Why? Because it is often a loading-led approach rather than a movement-led one.

Because it is often loading-led rather than movement-led, the bench/box squat is an example of an approach that can pattern bad movement, says @WSWayland. Share on XRather than dropping the load and focusing on good mechanics, a shoddy loaded squat to a box is still a shoddy partial squat. The then subsequent introduction of greater depth at crucial angles with the same loads means complete system failure more often than not. I’ve seen otherwise stable squats to a high box reduced to panic-inducing mornings with the mere introduction of an extra inch or two of depth. This is because the inherent pattern is still faulty, and more range of movement won’t fix that. Things like proper forward knee movement and minimization of trunk lean are abandoned in favor of “finding” the box.

As you can see, there are two strategies here that try to improvise pathways to a better squat: One manipulating simple mechanics to allow for greater movement, the other incremental to foster movement under load. Movement-led approaches to fundamental movement patterns allow for long-lasting capabilities rather than shortsighted compensations.

Here are a few strategies for tying all this thinking together:

1. Have a Written Strategy for Navigating the Path to a Back Squat

The one we use at Powering Through Performance looks something like this.

6 Point Kneeling > Bodyweight > Bodyweight+ > Anchored Squat > Anterior Squatting > Back Squat

Because we have a number of coaches coaching different athletes over time, we can pick up where another has left off. Having an agreed-upon progression framework prevents us from undermining each other’s work. Do we deviate from this structure as needed? Of course we do—a path allows for deviation from that path.

While yours could be different from mine, having progression strategies in place for most exercises is not a bad thing. There is also no harm in selling the progression strategy to athletes so they can see a viable pathway to achieving outcomes both they and the coach want.

2. Understand the Difference Between Building Dependencies and Competencies

This sounds outwardly simple. But it is easy for coaches to make what seem like logical deductions to tackle problems and end up building further compensations that hinder the athlete in the long run. I’ve seen this in athletes who have been coached into a corner with dependencies on things like landmine/goblet squats (usually stemming from fear of load) or partial squats (load addicted, but unwilling to step back). The trickiest dependency to navigate is the one built from injury or injury anxiety, either real or imagined, or enforced through a poor choice of words from another coach or physio.

3. Have a Regression Strategy

A lot of traveling athletes who often conduct training alone and/or see their coach infrequently will, on occasion, need regression. Athletes will often build dependencies all on their own. I have had terse conversations with athletes unwilling to try anything other than their chosen, unproductive squat variant, sharing a regression plan and a subsequent follow-on progression strategy. You are more likely to get good buy-in if they understand why regression occurs and the benefits of doing it.

4. Understand That Anchored Squatting Is a Pathway or a Plan B, Not a Holding Pattern

The general population can thrive on novelty and modest difficulty, so the rationale of anchored variants makes more sense here than in athletic populations. Anchored movements can be learning movements—a supplementary/plan B exercise as circumstances dictate. Problems start to creep in when they’re used as a crutch movement because, generally, loading isn’t really high enough to manifest any meaningful lower body stress.

The aim of this post wasn’t to coach back squats per se, but to think about how we get there. A lot of coaches do this intuitively, but it’s clear, evidenced by what we often see on social media, that not everyone is quite so intuitive. While this acts as excellent fodder for disparaging others, I ask why these situations occur.

There are a number of steps between taking someone from being squat-deficient to a full bodyweight squat to the finally axially loaded endgame. For the strength training inclined, it’s easy to be full of answers. However, when you are confronted with populations of athletes that are perhaps less inclined towards lifting—especially those willfully combative when it comes to change or progressing/regressing—having a plan in place is part of winning the battle.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

[mashshare]

References

Charlton, J.M., et al. “The Effects of a Heel Wedge on Hip, Pelvis and Trunk Biomechanics During Squatting in Resistance Trained Individuals.” The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 2017;31(6):1678-1687.

Schoenfeld, B. “The Biomechanics of Squat Depth.” NSCA