For much of the last 50+ years, the interest and buzz surrounding new training methods and technologies has mostly been very lifting- and barbell-centric. As the weight room slowly but surely became the norm for training athletes of all ages and levels, the relative advantage weight training gave teams and athletes began to level out. With expertise and use of those protocols becoming more standard, coaches began searching for the next series of ideas, philosophies, and technologies that could give them back that relative advantage.

Over the past two decades, sprinting and speed development—presented in many different methods and philosophies—have become that “difference-maker” that the weight room was from the beginning. While there are still programs that don’t focus on sprinting as a major developmental tool (just as some still lack in weight room strength training), it has become a mainstream aspect of athletic performance training. As coaches began to master the basics of speed development—or if not mastered, at least used with proficiency—as they did with strength training, they’ve begun to seek out technologies and tools that can assist them develop faster, more explosive athletes.

As coaches began to master the basics of speed development, as they did with strength training, they’ve begun to seek out technologies and tools that can assist them develop faster, more explosive athletes, says @MarkHoover71. Share on X[vimeo 1001669720 w=800]

Video 1. OHM straight leg bounds (Prime Times).

In search of speed development knowledge, I visited XPE Sports during their NFL Combine prep in 2023 and noticed that the athletes were using an interesting machine in preparation for their SHREDmill runs. It had handles attached to a run cord (similar to a 1080 Sprint or Run Rocket) and could be set to a static load. This load held the athlete at a set velocity. Once reached, XPE staff could set a velocity as low as 0.1 MPH or as high as 10 MPH. This allowed the coaches to use the device as a sled of varying loads without having to adjust any weight.

I was instantly drawn to this new technology and sent a picture to my colleagues at SimpliFaster with the text “You need to see this.” The machine was the OHM Run, built by Optimal Human Motion. The device is designed to optimize strength and power training through the use of accommodating resistance. This allows the athlete to perform functional, ground-based movements against not just a fixed speed but also a fixed load, if they choose. While most commonly used in place of a sled as at XPE, the OHM Run can be used in countless ways and for much more then speed development.

Still, what jumped out at me was its ability to be used in place of a traditional sled. The OHM Run isn’t designed to be only a resisted sprint tool (such as a 1080 Sprint or Run Rocket)—it’s meant to train strength and power in a consistent manner regardless of how fast the athlete attempts to move. Its versatility gives you the ability to use it as a sled, resistance sprint tool, or a strength training machine.

Using the OHM for movements such as heavy walks (that can simulate a sled push but with isokinetic load), resisted sprints, rotational movements, or loaded change of direction are just a few of the options. This machine can be used to help the athlete create certain angles and positions that can’t really be “cheated” and still done effectively. It also gives instant feedback to the athlete on peak and mean power outputs of the exercise. All this without having a sled and weights taking up space, or taking time to load and unload. In addition, the OHM Run can be used for a multitude of rotational, press, and pull movements. Its variable usage really sets it apart, making it less of a sprint device and more of a Swiss Army Knife tool.

[vimeo 1001687921 w=800]

Video 2. OHM heavy walks.

[vimeo 1001688814 w=800]

Video 3. Block starts from the OHM Run.

For this round table-type collaboration, Mike Wright (Athletic Trainer at South Sioux City High School) and Vien Vu (Physical Therapist at Stanford University) will pass along some insights on their experiences with applying the OHM Run.

Mike Wright

When our high school first received the OHM, one of the biggest benefits was its ease of setup and the ability to quickly integrate it into our sessions. We were primarily focusing on power in the early acceleration phase. The OHM allowed our student-athletes and coaches to concentrate on proper shin angles and strengthening the plantar flexion muscles.

In the early acceleration phase, it’s crucial to work on the plantar flexion muscles due to their significant role in acceleration, as opposed to doing seated or standing calf raises. Chris Korfist has recently emphasized that “if your first step doesn’t reach three meters per second, you have a lower ceiling for your running potential.” (Korfist – Podcast – Talking Pitt Episode 28 -Using 1080 Sprint to Getting your Athletes Faster.)

The OHM is a great tool for providing the necessary resistance and targeting the shin angles to build the power required for increased speed.

Another benefit of the OHM is its versatility, both with combining other pieces of equipment and working on qualities outside of acceleration training. An example would be how our throwing coach on the track team also had the opportunity to use the OHM with his athletes. He incorporated it into the indoor training for his throwers, especially with the discus throwers, to enhance their rotational power.

The OHM is a great tool for providing the necessary resistance and targeting the shin angles to build the power required for increased speed, says Mike Wright @ssc_cardpower. Share on XWhen using the OHM in the weight room, we incorporate it with our SHREDmill in a performance circuit. The SHREDmill has been a fantastic tool for our power work in the weight room. Our school has been incorporating SHREDmill workouts since January of this year, and we have seen great results. The OHM is a great addition to supplement the work already being done with the SHREDmill.

If time is not a limiting factor, we try to measure an athlete’s vertical jump at the beginning of every round. When the vertical jump decreases, the athlete will not complete another circuit. An example of a round in the performance circuit we might use with the OHM is as follows:

- Split Stance Band Assisted Vertical Jumps: 1 x 4 each

- Altitude Drops into Split Stance: 1 x 4 each

- Tall Fall Lean Unresisted 15-20 yard run

- OHM – Heavy Resisted Marching: 1 x 4 each

- Yuris: 1 x 3 each

- SHREDmill – Gear 2 Run (start with a resistance of 6 and progress as needed)

- Spring Ankle Isometric: 10 seconds each

This is just one example of how we would use the OHM in the weight room. There are many different practical applications that we could incorporate it into. When we have time constraints, we would simply pair it with our Gear 2 SHREDmill, and, depending on the athlete’s training age, would go from anywhere to 2-5 sets of each.

Vien Vu

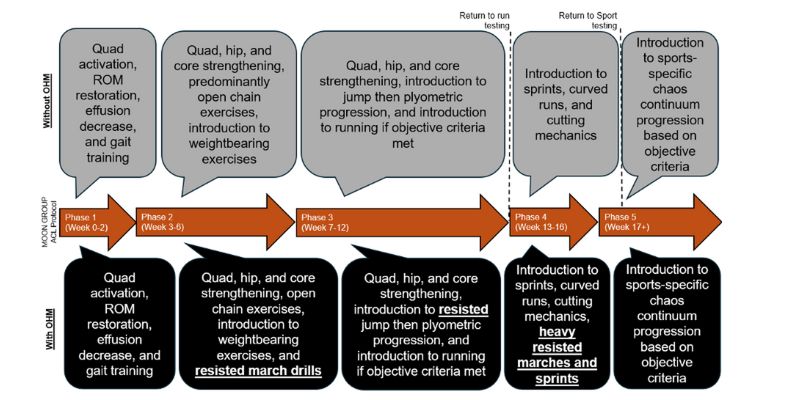

Not only can the OHM be useful for performance, but it also allows for earlier introduction of the above-mentioned motor learning drills when individuals may not tolerate ballistic movements such as running. For example, those rehabbing after ACL reconstruction may not be allowed to run until week 12 based on MOON group guidelines.1 This leaves most athletes performing dynamic exercises such as hinge and squat pattern variations for 6 weeks, which may be repetitive and solely work on strength.

The OHM allows practitioners to complement traditional strength training with resisted movements to work on shin angles and functional trunk stability up to 6 weeks earlier in their rehab (Figure 1).

This allows for strength development, but also speed and biomechanics. A lot of selected exercises are more than walking and bodyweight movement, yet are below that of ballistic exercises. Such principles are useful for athletes restricted from ballistic exercises because of issues like bone stress injuries, lower extremity surgeries, and lumbar spine injuries.

- Heavy resisted march

- Resisted reverse walking (emphasis on terminal knee extension)

- Resisted lateral marches

- Resisted lateral walks, marches, and crossover steps

- Overhead marches (emphasis on pelvis position and core control)

My Experience

Currently, our main use with the OHM is as part of our SHREDmill performance circuits. We will begin by setting the OHM to its heaviest isokinetic setting (0.1 MPH) and have our athletes lean and extend as if they were pushing a heavy loaded sled. The lean and drive at the set, ultra-low speed allows our athletes to drag their foot, setting up a shin angle and foot placement (after they can snap their foot down under their hip) that is conducive to what we call Gear 1.

Not only can the OHM be useful for performance, but it also allows for earlier introduction of motor learning drills when individuals may not tolerate ballistic movements such as running, says @MuyVienDPT. Share on X[vimeo 1001692186 w=800]

Video 4. Snapping the foot under the hip.

These angles allow the athlete to experience horizontal force and be forced to present it correctly to the ground in order to be able to move. Our cue is “inside edge, ball of the foot” to ensure correct force application.

We pair these two runs at 0.1 MPH with SHREDmill bounds and a “Yuri” movement.

As we progress through our performance circuit, we use increasing speeds of 3.0-6.0-8.0 MPH on the OHM Run paired with Gear 2 and Gear 3 runs on the SHREDmill. We do this to be able to surf the entire range of speeds and shin angles. We believe each increasing velocity will allow the athlete to feel the needed foot placements and resistance levels to better self-organize themselves into the optimal angles.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

1. Wright RW, Haas AK, Anderson J, Calabrese G, Cavanaugh J, Hewett TE, Lorring D, McKenzie C, Preston E, Williams G; MOON Group. Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction Rehabilitation: MOON Guidelines. Sports Health. 2015 May;7(3):239-43. doi: 10.1177/1941738113517855. PMID: 26131301; PMCID: PMC4482298.