Thunder cracked as we reached the summit of Longs Peak. After the grueling 7-mile ascent, with its 5,100-foot elevation gain, we arrived just as the daily storm rolled in. No matter the season, storms are a constant threat in the Rocky Mountains and this July day was no exception. Anyone familiar with mountainous terrain understands that the summit during a thunderstorm is the last place you want to be—the mountains teach harsh lessons about properly timing your ascent and peak. Whether we started too late or maintained too slow a pace became irrelevant: we had peaked at the wrong time.

I have always been in the mountains. Born in Greeley, Colorado—as my Dad was finishing his doctorate at the University of Northern Colorado—I’ve kept a connection to those high peaks that runs deep. Despite years of climbing experience, and working as a climbing guide in college, I had never attempted a “14er”: one of Colorado’s legendary peaks towering above 14,000 feet.

Reflecting on this ascent got me thinking about how, as coaches, we must be strategic and pragmatic with our seasonal objectives in order to not top out too soon. Our season’s structure should align with our ultimate goal. Like mountaineers planning their summit attempt, timing becomes everything, whether that goal is advancing from regionals or achieving victory at the state or national level. Whatever that goal, a common phrase in the outdoor industry can be applied to coaching as well: “Proper prior planning prevents (p*ss) poor performance.”

It’s our responsibility to plan an effective and safe top-out when it matters most.

Like mountaineers planning their summit attempt, timing becomes everything, whether that goal is advancing from regionals or achieving victory at the state or national level, says @DillonMartinez. Share on XThe challenge of timing athletes’ peak performance can appear daunting. However, both research and the experience of elite coaches offer valuable guidance. Studies demonstrate that a properly executed taper can enhance competition performance by approximately 3%, with improvements ranging from 0.5% to 6.0% (Majika, 2012; Meur et al., 2012; Bosquet et al., 2007). Just as a mistimed summit attempt leaves climbers exposed to danger, an improperly planned competitive peak leaves athletes vulnerable to underperformance when results matter most.

Understanding the Taper

Athletes’ performance potential balances between fitness and fatigue. Throughout the season, both elements increase, but fatigue often masks the true fitness, strength, and speed gains accumulated during training. A proper taper reduces fatigue while maintaining, or even increasing, these performance aspects; this, then, allows athletes to access their full adaptive potential when it matters most.

A proper taper reduces fatigue while maintaining, or even increasing, these performance aspects; this, then, allows athletes to access their full adaptive potential when it matters most, says @DillonMartinez. Share on XRecent research examining elite sprint coaches’ technical practices reveals that successful tapering transcends simple volume reduction; it requires systematic progression toward competition-specific intensity (Agudo-Ortega et al., 2024). Agudo-Ortega et al. (2024) surveyed numerous professional track coaches who all had experience working with Olympic-level sprinters. Of the hundreds of research articles I have reviewed while working on my doctorate (which focuses on speed coaching), this work by Agudo-Ortega et al. has been one of the most thought-provoking—I highly recommend taking the time to read it.

Upon review of the data, the researchers discovered that all the coaches who participated in the study implemented some form of tapering phase into their competitive season, though their approaches varied in duration and structure. To get a better understanding of these differences, lets first look at some basics of the taper.

The Physiology of Fatigue: Why Tapering Matters

Understanding fatigue’s multifaceted impact on athletic performance illuminates why proper tapering proves essential. Taylor et al., (2016) produced a foundational article that outlines the effects that fatigue, in its many forms, imparts on the muscles. Fatigue manifests through several distinct mechanisms, each significantly affecting performance:

- Neuromuscular fatigue—at the neuromuscular level, fatigue diminishes motor unit recruitment and reduces power output, typically requiring 24-72 hours for full recovery.

- Metabolic fatigue depletes energy stores and compromises energy systems, necessitating 12-48 hours of recovery.

- Structural fatigue, characterized by micro-damage to muscle fibers, can take 48-96 hours to resolve.

- Central nervous system fatigue and hormonal imbalances, perhaps most significantly, can require 72-120 hours for complete recovery.

Athletic performance deteriorates under fatigue through several key mechanisms. A decline in neural efficiency presents as a primary concern. Research indicates that athletes who experience central nervous system fatigue exhibit a decrease in the rate of force development, reduced motor unit synchronization, and diminished neural drive (Tornero-Aguilera et al., 2022; Taylor et al., 2016). These deficits result in slower explosive movements, less coordinated actions, and decreased maximum force production—the specific qualities that are crucial for athletes to perform at their best.

Research indicates that athletes who experience central nervous system fatigue exhibit a decrease in the rate of force development, reduced motor unit synchronization, and diminished neural drive. Share on XA compromised metabolic system further compounds these issues. The seminal piece by Sahlin (1992), does a lot to explain how metabolic fatigue impacts our athletes. Sahlin points out that training-induced fatigue affects multiple energy systems, with phosphocreatine stores showing depletion, glycogen reduction, and compromised aerobic efficiency. These deficits directly impact immediate energy availability, sustained power output, and recovery capacity between efforts.

The Art and Science of Training Phases

Now that we understand how fatigue occurs and its impact on athletes, we can begin to strategically plan our training phases. Just as a composer creates a symphony through carefully designed movements, each adding complexity and depth to the piece, elite coaches develop their training programs in structured phases that work in concert with one another. Their approach reflects the natural progression of athletic development, moving from fundamental strength to explosive power, and ultimately to performance tailored for competition. But the original motif of the piece, to a well-trained ear, will be able to be heard throughout each movement.

Movement One: Starting with the Base (the trailhead)

Tackling Longs Peak with my brother-in-law and a friend, we started well before the sun was up. The general idea of starting the hike so early was to ensure ample time to climb, hang out at the summit, then start the trek back before the afternoon storms came in. With that thought in mind, we took our first steps on trail at 3am—we had a plan and were able to start exactly when we’d hoped, with clear skies and no one else around. The first few hours were easy going—the incline was not yet severe and the altitude hadn’t started to get the best of us…

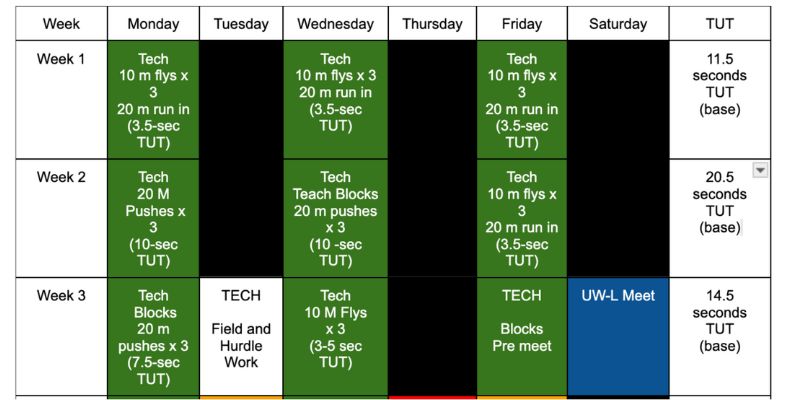

Much like the initial portion of that hike, the start of my track season is almost painfully gradual. For my high school sprinters, the first two weeks of the season are extremely low volume. In fact, we don’t even have practice on Tuesday or Thursday for the first two or three weeks of the season. This is because I do not view my track athletes as only track athletes.

Last year (2023), both the boys’ and the girls’ basketball teams played in the state championship game, then athletes from those teams reported to track practice the following Monday. If I planned my track season in a vacuum, my athletes would never recover from the long basketball season, let alone the taxing effect that sprinting has on the central nervous system. Our athletes are not ours alone: we need to consider their entire year when we plan our season rather than seeing our season as the macrocycle. Below is an example of my first three weeks of the track season. In a previous article, I explained how I use time under tension (TUT) to plan out my entire season (for a refresher, you can find that piece here).

Our athletes are not ours alone: we need to consider their entire year when we plan our season rather than seeing our season as the macrocycle, says @DillonMartinez. Share on X

Notice how we don’t go from practicing three days a week right to five days a week. We start with three, then four, then five. This ensures adequate time for the body to adjust to the novel stimulus of the new season before we hit it hard starting on Week 4 (although hard for us is subjective).

I don’t go about the base phase in this manner because I am a wizard and thought of this all on my own—this is simply what the research has shown as best practice. Other examples of some methods that lend themselves nicely to the base phase as identified by the literature are:

- Tempo runs of 200m or so at 60-70% of max speed that focus on perfect technique with 2 minutes of rest (as identified by 85% of coaches in the Agudo-Ortega study).

- Hill runs, with athletes performing eight to ten 60m ascents at 70% effort, naturally enforcing proper mechanics while building strength and endurance.

- Whole sessions focusing on technical progression and movement pattern development that will prove crucial in later phases (stay tuned for a dissertation coming out in May focusing on how successful speed coaches teach sprinting as a specialized skill).

Movement Two: Crafting Power and Precision (the Push Above the Trees)

As dawn broke and we emerged from Goblin’s Forest, the real work of our hike began. The well-maintained trail gave way to increasingly rocky terrain, and the protective canopy of trees disappeared, leaving us exposed to the elements. This transition marked our first serious test—a steep series of switchbacks that demanded more from our legs and lungs as we pushed toward Chasm Junction. The thin air above 11,000 feet forced a new awareness of our breathing and movement efficiency. Gone was the gentle warm-up of the forest trail; now each step required more precise placement and greater energy expenditure.

This section of the climb mirrors the transition my sprinters face as they move from their base phase into more demanding training. Just as the mountain demands more from climbers above the tree line, this phase asks athletes to step out of their comfort zone and face new challenges. The protective “cover” of basic conditioning gives way to more specialized work, and just like those early morning switchbacks, each training session now requires greater precision and intensity.

As athletes master the fundamentals outlined in the first phase, my high school sprinters progress to more specific training strategies that will elicit a more profound response. The focus shifts from base strength, technique, and low-volume exposure to explosive power production. This is a transformation that requires both precision and patience on the part of the coach and the athletes.

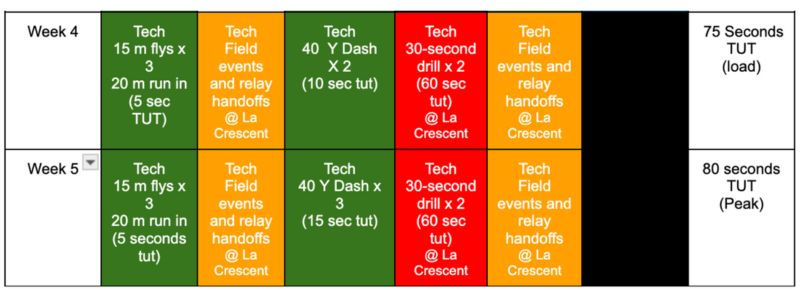

The week’s structure maintains its rhythm, but changes its tune. We are now at 5 days a week. Speed endurance work is going to be introduced for the first time of the season, and speed work is going to be stretched out ever so slightly. Instead of 10m flys, we will do 15m flys. Instead of 20m pushes out of blocks, we will run two 40-yard dashes.

As stated, speed endurance work intensifies during this phase. Because the athlete’s body has built up some familiarity with the new stimulus, more volume can be added safely. This is in line with what every elite coach in the Aguado study emphasizes as important during this phase of the training cycle.

Movement Three: Adding a Gear (The Boulder Field)

After 5.5 miles and 3,300 feet of elevation gain in the hike, we arrived at the Boulder Field. This iconic section of Longs Peak offers a deceptive reprieve; while the elevation gain eases, each step requires deliberate focus as you navigate the maze of car-sized rocks. A single misplaced foot could end your summit bid, yet there’s a psychological boost in reaching this milestone. The hard push above the tree line is behind you, but the technical challenges of the Keyhole Route still lie ahead.

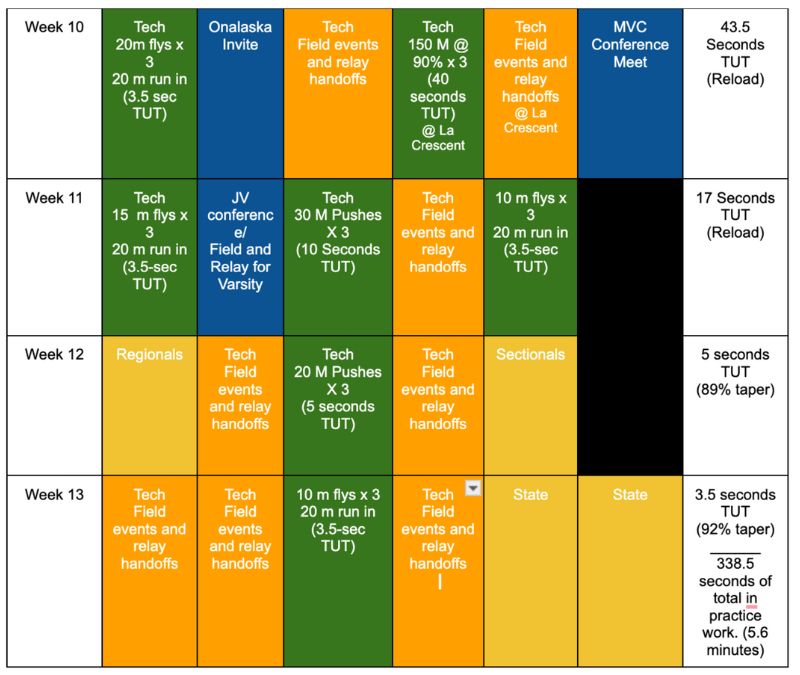

This phase mirrors the first taper in our sprinting program, where we begin to capitalize on the previous weeks’ work. Just as hikers must balance their desire to move quickly through the Boulder Field with the need for precise foot placement, we now shift our training focus from volume to quality. Meet schedules become a crucial consideration, requiring us to adjust our training stimulus accordingly. Our speed endurance work transforms into three technique-focused “shakeouts” of 150m at a controlled 90% pace. This represents our first significant volume taper—dropping to 45 seconds of Time Under Tension (TUT), a 56% reduction from the previous week. The taper continues progressively, reaching 75% in week 7 and 93% in weeks 8 and 9.

Movement Four: The Final Push (Keyhole to Summit)

After the Boulder Field comes the most technically demanding section of the climb—the infamous Keyhole formation. Passing through this distinctive notch in the rock marks the point of no return. The relatively straightforward hiking ends, and true mountaineering begins. Like our transition into championship season, each section beyond the Keyhole demands perfect execution under increasing pressure.

The Narrows comes first: a ledge traverse where focus is paramount. Hikers must move efficiently while maintaining absolute precision, much like our athletes during the reload phase of weeks 10-11. Here, we dramatically reduce volume to just 21% of our peak week, but maintain laser-sharp technical execution through short, crisp sessions like our 20m flys and precise relay handoffs. Like traversing the Narrows, there’s no wasted movement—every step must have a purpose.

Then comes the Trough—a steep gully of loose rock that tests resolve. This mirrors our regional and sectional weeks (week 12), where we further reduce training load to just 5 seconds of Time Under Tension. Just as climbers must carefully pick their line up the Trough, we strategically decrease volume while maintaining enough intensity to keep our athletes sharp. A misstep in either environment could prove costly.

Finally, there’s the Homestretch—the last steep pitch to the summit. Like our state meet week (week 13), where we cut to just 3.5 seconds of TUT (a 92% taper from peak), this final section demands everything you have left while requiring perfect technical execution. Just as a climber must execute precise movements on the exposed granite slabs despite fatigue and elevation, our athletes must perform at their absolute best when it matters most.

Just as a climber must execute precise movements on the exposed granite slabs despite fatigue and elevation, our athletes must perform at their absolute best when it matters most. Share on XThe parallel continues to timing—summit the peak too late, and afternoon storms threaten success. Peak your athletes too early, and months of preparation may fall short of their potential. But when timed right—when you hit the summit under clear skies, or when your athletes step onto the track at the state meet fresh and fast—all the calculated preparation pays off.

Adapting Principles to Specific Sports

But what about other sports? While the fundamental principles of tapering remain constant, their application must be as unique as the sport itself.

Football: The Season-Long Summit

Football presents a unique challenge in performance peaking. Imagine climbing not one mountain, but a range of peaks that stretches across an entire season. The goal isn’t simply to reach one summit, but to maintain elevation while preparing for the highest peaks during playoff season.

Last winter, Tom Lee, the head football coach at Aquinas High School (State Champs in 2021, 2022, and 2023), was helping me run off-season speed work with a mix of football, volleyball, basketball, baseball, and track kids. I asked him how he prevented burnout throughout the long season, to which he smiled and said: “People wouldn’t believe how little we practice.”

This concept of minimizing practice time while maximizing effectiveness has fascinating applications in football. Consider a system that begins with focused 90-minute practices in the preseason, built around just three core elements:

- Positional skills

- Team execution

- Special teams

As the regular season progresses, practice time could drop to 60 minutes, with one day per week dedicated entirely to film study and recovery. The weight room focus shifts from general strength to purely explosive movements with light weight. When playoffs arrive, this minimalist approach tightens further—45-minute practices that eliminate everything but essential game-speed reps, explosive lifting sessions early in the week, and increased recovery time. This strategic reduction in volume allows players to maintain peak power output when it matters most, while the maintained intensity of shorter sessions keeps skills sharp. The keys to this approach aren’t revolutionary methods, but rather the disciplined removal of non-essential work; understanding that in a violent sport like football, less can truly be more when that “less” is precisely what the athletes need to succeed.

Basketball: The Tournament Gauntlet

Like a climber transitioning from the relative stability of the Boulder Field to the exposed Keyhole Route, basketball teams must navigate their own technical crux during tournament season. The physical demands shift dramatically, from managing regular season games with recovery days between, to potentially playing three or four high-stakes games in rapid succession. Like we had to carefully manage our energy through each challenging section of the Keyhole Route, basketball coaches must orchestrate their team’s energy expenditure with precision, knowing that each game could require maximum output.

This tournament gauntlet demands a unique tapering approach, one that differs significantly from our track model or football’s season-long crescendo. Think of it as preparing for multiple summit attempts in quick succession, each requiring peak performance. Recent research suggests that successful basketball programs often implement what I call a ‘stepped taper’: reducing practice intensity by 40% two weeks out, then another 30% the week of tournaments, while maintaining short, explosive sessions that mirror game intensity. These sessions typically last no more than 45 minutes and focus entirely on tactical execution and shooting rhythm, like a climber rehearsing crucial moves before a difficult pitch—every movement must serve a specific purpose.

Back to the Track

As I extensively outlined above in my program scheduling, track and field represents perhaps the purest application of tapering principles, where success or failure becomes immediately measurable in hundredths of seconds or fractions of inches. Agudo-Ortega at al., (2024) point out that elite sprint coaches have developed remarkably consistent patterns in their approach to peaking, though their specific methods show interesting variations.

The foundation of their success lies in technical preparation. Every single elite coach in the study (Agudo-Ortega et al., 2024) emphasizes technique work before sprint sessions, treating it not as a mere warm-up, but as deliberate technical preparation. They progress through a careful sequence: muscle activation, mobility work, technical drills, plyometric preparation, and finally progressive sprint build-ups.

As Agudo-Ortega et al. (2024) uncovered, the duration of the taper itself shows fascinating variation among elite coaches. Some prefer a 15-day taper (35.7%), others opt for 10 days (21.4%), while another group extends the taper to 30 days (21.4%). I used 20 total days of taper in the program outlined above. This variation underscores a crucial point: the optimal taper length must be individualized based on event specifics, training history, recovery capacity, and the competition schedule.

The optimal taper length must be individualized based on event specifics, training history, recovery capacity, and the competition schedule, says @DillonMartinez. Share on XMonitoring and Adjustment: The Art of Listening

Similar to how an experienced mountaineer reads the mountain’s subtle signs—such as the changing wind patterns, the feel of the rock, and the shifting weather—successful coaches must develop an acute sensitivity to their athletes’ readiness. Think of it as creating your own weather station at base camp—the objective data (such as heart rate variability, jump testing results, and velocity tracking) are your barometer readings and wind speeds. Equally crucial are the subjective measures—your athletes’ mood, movement quality, and perceived readiness, these are like those subtle environmental cues that experienced climbers interpret instinctively.

The mountain teaches us that conditions can change rapidly and require immediate adjustments; similarly, the taper period demands constant vigilance and readiness to adapt. When I watch my sprinters during their final preparation phase, I’m not just looking at stopwatch readings or counting repetitions, I’m listening for the rhythm of their footfalls, watching the crispness of their movements, sensing whether they’re hitting their crescendo at the right moment.

When I watch my sprinters during their final preparation phase, I'm not just looking at stopwatch readings or counting reps, I'm listening for the rhythm of their footfalls, watching the crispness of their movements. Share on XAs a conductor fine-tunes each section of the orchestra before the performance, we must listen not just to the individual instruments, but to how they harmonize together. This artistic element of coaching, this ability to read and respond to both data and intuition, often makes the difference between a successful peak and a missed opportunity.

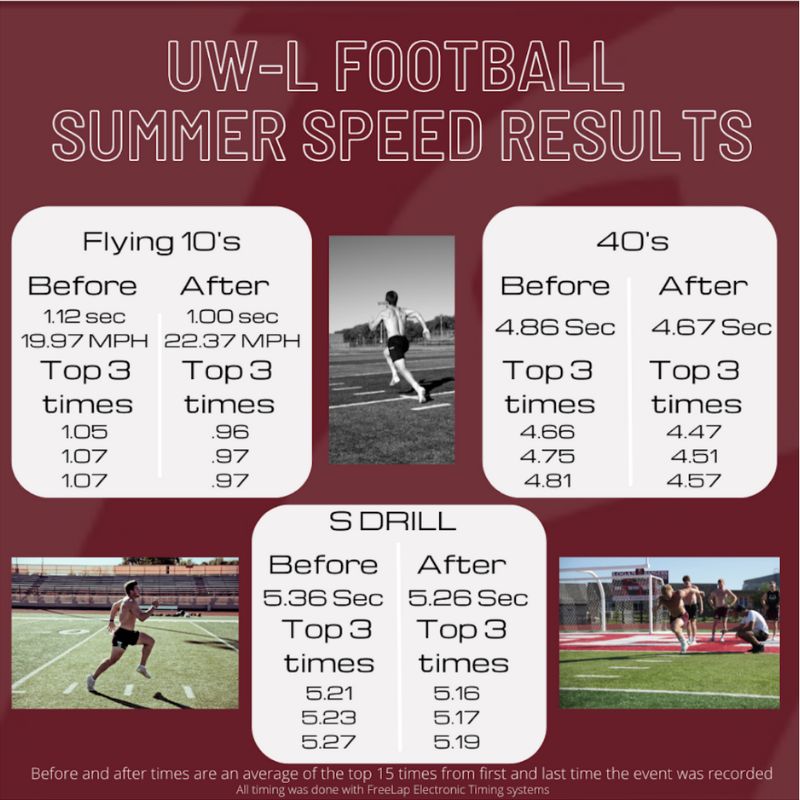

Real World Example

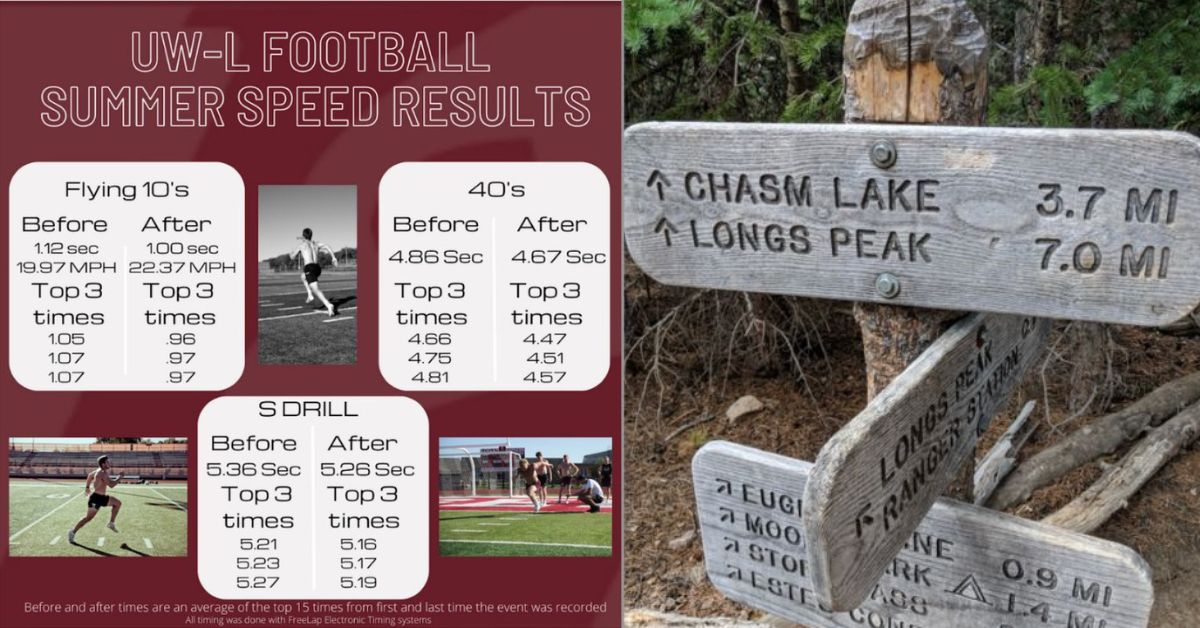

In my previous article, outlining my plan for the 2024 Wisconsin Track season, I laid out my ideas on prioritizing speed and my method of using time under tension to plan out my season’s workouts. I briefly mentioned the taper aspect of my plan, but didn’t spend nearly the amount of time on it as I did here. The examples provided were my exact 2024 track season plan.

How did it go?

To put it simply, the plan worked. The fastest 10m fly times of the season (both average and individually) were recorded on our final day of practice before we ran at the state meet. We then went on to run our best races and times of the year when it mattered the most. As a coach, that is all that I could hope for.

The Final Descent

That day on Longs Peak, we were forced to make a hasty retreat from the summit as lightning crackled around us. The descent was treacherous—every step calculated, every movement precise, despite our urgency to escape the incoming storm. Yet even in that moment of intensity, there was a lesson: sometimes our greatest achievements come with imperfect timing, teaching us to be even more precise in our future planning.

Just as mountaineers learn from each summit attempt, coaches evolve through each season. The science is clear: A well-executed taper can unlock performance improvements of up to 6% (Majika, 2012), but achieving this requires both art and science. Whether you’re coaching football players through a grueling season, preparing basketball teams for tournament gauntlets, or fine-tuning track athletes for championship performances, the principles remain consistent: systematically reduce volume while maintaining intensity, monitor both objective and subjective markers of readiness, and individualize your approach based on your athletes’ needs and responses. The success of my 2024 track season wasn’t just about the training plan, it was about timing our summit attempt perfectly.

Like that successful summit attempt, peaking athletes require careful planning and precise execution. The mountain showed that it is not enough to simply reach the top, you must get back down safely. In athletics, this means understanding that peak performance is not a single moment, but a window we need to sustain through championships.

References

Agudo-Ortega, A., Salinero, J., Sandbakk, Ø., De La Cruz, V., & González-Rave, J. (2024). Training practices used by elite sprint coaches. International Journal of Performance Analysis in Sport, 1–16.

Bosquet, L., Montpetit, J., Arvisais, D., & Mujika, I. (2007). Effects of tapering on performance. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 39(8), 1358–1365.

Meur, Y., Hausswirth, C., Mujika, I. (2012). Tapering for Competition: a review. Science & Sport. 27 (2), 77-87.

Mujika, I. (2012). Endurance Training – Science and Practice (2nd Edition). Physiology and Training.

Taylor, L., Amann M., Duchateau, J., Meeusen, R., Rice, C. (2016). Neural Contributions to Muscle Fatigue: From the Brain to the Muscle and Back Again. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 48(11), 2294-2306

Tornero-Aguilera, J., Jimenez-Morcillo, J., Rubio-Zarapuz, A., & Clemente-Suárez, V. (2022). Central and peripheral fatigue in physical exercise explained: A narrative review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(7), 3909.

Sahlin, K. (1992). Metabolic factors in fatigue1. Sports Medicine, 13(2), 99–107.