[mashshare]

One of the most frequent questions we hear from visiting coaches at ALTIS is “How did you develop your ‘coaching eye’?”

The answer is really quite simple: We have watched a lot of athletes do stuff, and we paid very close attention while doing so! In the days when iPhones, inexpensive high-speed cameras, biomechanical analysis apps, and wearables did not exist, watching closely was our only option to better understand what was going on.

Now that these technologies are available to us, it is imperative that we don’t forget about the importance of developing our “real-time” eye. If we do this correctly, technology can support us through the process, giving today’s coaches a leg up on those of us who had to do it the “old-fashioned” way.

We suggest a strategic implementation of technology. For example, combine repetitions using Freelap with ones that do not, try to estimate the repetition time before checking the app, watch video after sessions and limit it during them, etc.

It is with this objective in mind that we offer the following method of analysis that we use at ALTIS in support of our daily coaching. It is called the ALTIS Kinogram Method, and it is based on an analysis system that is more than a century old.

This article makes up one single section of the Sprint Module within the new 12-module ALTIS Essentials Course, which we have designed to be the initial step into all coach education pathways. It provides a concise introduction to core topics that underpin successful coaching in all sports. We crafted this exciting new addition to the ALTIS Education Platform for individuals seeking to gain a succinct overview of essential coaching theory and its application, in a condensed short-course format. We are extremely proud of the work that has gone into this course, and if you haven’t already taken the foundation course, we encourage you to check it out!

What Defines Sprinting?

First, before delving into the details of the analysis method, we need to have a common understanding of the definition of “sprinting.” Any discussion pertaining to “sprinting” is truly referring to running at maximal or near-maximal speeds. The overarching aim of sprinting is for the performer to propel their body down the track, pitch, field, or court as fast as possible.

If we consider this task simply, the athlete who can most appropriately project their body forward in the shortest time frame, and maintain top-speed the longest, will be the most successful. This type of motion has specific kinematic characteristics differentiating its gait from walking, jogging, or sub-maximal running. Understanding what the gait cycle looks like is therefore a key tool in being able to error-detect and correct.

Gait

The gait cycle is the basic unit of measurement in gait analysis. It begins when one foot comes into contact with the ground and ends when the same foot contacts the ground again.

Key landmarks in the gait cycle include:

- Touch-down: The point where the foot contacts the ground.

- Stance phase: The weight-bearing phase of the gait cycle. During the stance phase, the foot is on the ground acting as a shock absorber, mobile adapter, rigid lever, and pedestal, as the body passes over the support leg. Stance ends when the foot is no longer in contact with the ground.

- Toe-off: The beginning of the swing phase of the gait cycle where the foot leaves the ground.

- Swing phase: The phase where the foot is no longer in contact with the ground and the free leg is recovering forward in preparation for ground touch-down.

- Flight phase: Seen in running only, this represents the period when neither foot is in contact with the ground. This includes the swing phase above.

Humans transition from a walking gait to a running gait at a certain speed threshold—generally 2.0–2.7m/s (Schache et al., 2014). The demarcation between walking and running occurs when periods of double support during the stance phase of the gait cycle (both feet simultaneously in contact with the ground) give way to two periods of double float at the beginning and end of the swing phase of gait (neither foot touching the ground).

In running, there are no periods when both feet are in contact with the ground. As the athlete’s speed increases, less time is spent in stance. Jogging is normally seen at speeds of approximately 3.2–4.2 m/s; running at around 3.5 to 6.0 m/s; and sprinting anywhere upwards from there, depending on the individual.

Sprinting Gait

When approaching maximal speed, we see subtle gait differences to that noted in sub-maximal running. As running speed increases, time spent in swing increases, stance time decreases, double float (flight time) increases, and cycle time shortens. Generally, as speed increases, the initial contact changes from being relatively rearfoot to relatively forefoot. This is important to understand, as it relates to footwear, cognitive control of ground strike, and questions in regard to dorsiflexion and plantar flexion. We will discuss this further a little later in this article.

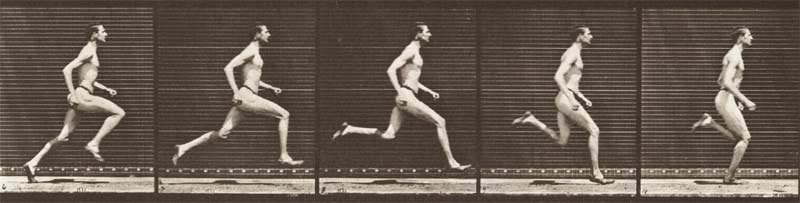

The ALTIS Kinogram

Eadweard J. Muybridge, in the 1880s, was the first to examine sprint kinematics, and display it in pictorial form. He used cinematographic and dynamographic techniques to explore vertical reactions during various gaits (Vazel, 2014).

“Chronophotography” soon replaced “cinematography.” A “kinogram” is a set of still pictures derived from a video source. First found in 1880s French physiology textbooks, it was also used to describe movement in USSR biomechanics publications in the early 1930s. Kinogram is often used as a synonym for chronophotography, but is differentiated through the optional choice of frame usage. With chronophotography, the time interval between still frames remains constant; with kinograms, we can select the frames as we feel are most appropriate (Vazel, 2018).

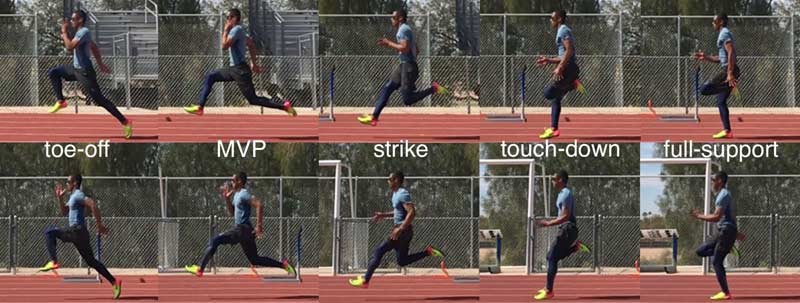

ALTIS coaches use five frames—three stance phase frames and two flight phase frames—which form the ALTIS Kinogram Method. The three stance phase frames are termed “touch-down,” “full-support,” and “toe-off.” The two flight phases are termed “MVP” (maximal vertical projection) and “strike,” which is the initial point at which the swing-leg hamstring is under maximal stretch.

With the overarching understanding that each athlete has their own individual mechanical solution to a movement puzzle, we will nevertheless offer our thoughts on what we feel are appropriate positions for each of these frames. It is up to individual coaches to determine what is appropriate for their own athlete group, and whether there should be any discrepancy from what we recommend.

Understand that we feel these are the most relevant positions for a sprint population. They are not necessarily the positions we would seek from a team sport athlete within the confines of playing their sport. Having said that, it is imperative that the coach and athlete understand the rules before breaking them. Understanding the most efficient acceleration and upright mechanics will form a starting point from which coaches and athletes can adjust appropriately to their own sport, event, or position.

First, we offer the reasons why we feel a kinogram method is a viable means to observe movement:

- Identify asymmetries and identification of when mechanics are abnormal: While asymmetries, in and of themselves, may not be a “bad thing,” observing left leg-right leg differences and tracking them over time will give coaches a good understanding of how the athlete will “normally” move. If we can identify an acceptable level of asymmetry for each athlete, we can then observe when the athlete falls outside of what we feel is an acceptable bandwidth around their “normal.” For this reason, it is important that we consistently observe their movement, and are critical with our analyses.

Understand that the athlete is a dynamic system and there will be variability around their movement solution from day to day and week to week. Our job as coaches is to improve their solution over time, while ensuring that any variability throughout this progression is within what is normal for them. This is how we keep athletes healthy—keep them moving in a way that is familiar to them, while patiently improving it over time.

- Track mechanical improvement over time: We run each athlete though a kinogram every week, and can thus visually depict any regression or progression of the technical model over time in an easy-to-understand manner. Comparing videos over time is very difficult—especially without expensive software. The Kinogram Method may take a little longer to build, but it is more effective in the long run.

- Compare kinematics across athletes and groups: As mentioned, it is important that we respect individual differences across our athlete groups. However, it is just as important that we respect biomechanical truths; coaching to an ”athlete-centered” solution does not give a coach permission to ignore these truths. Comparing across our athlete population, or with coaches across the world, can help a coach to better understand positions, cause and effect, progressions, and individual athlete differences. We encourage all coaches to post their kinograms on either social media or the private ALTIS Facebook Agora Group, to promote further discussion.

- Track impact of intervention, therapeutic or otherwise: The improvement of mechanics stems primarily from two sources—the volitional action of the athlete to incorporate a technical change, or the improved efficiency of movement brought on through a therapeutic intervention. Regardless of the cause of the change, a kinogram is a simple way to track change over time and much easier than high-speed video, which may require expensive applications.

- Improve understanding of key positions, and how/what we can do to affect them: It’s one thing to identify key positions; it’s another altogether to understand how to interpret them, and use this interpretation to affect change. Still frames make it much easier for coaches to identify aberrant positions than real-time observation and video review. While it is important for coaches to improve their observational abilities, a kinogram can act as a “bridge” and provide context to the positions that we feel are important.

- Gain a better understanding of individual athlete solutions: Over time, coaches will become comfortable with inter-group bandwidths and, once the kinogram process has been repeated multiple times with each athlete, they will become more knowledgeable about the unique mechanics of each athlete.

- Simple feedback process to athlete, given visual feedback that they can gain an understanding of quickly: Perhaps most importantly, a kinogram is an effective and efficient way for a coach to discuss mechanics with an athlete. At every level, it is important that an athlete understand the importance of improving technique. The kinogram method can provide a visual for the athlete to refer to.

- Allow for better communication between athlete and coach, by building a common language: As above, the kinogram affords an opportunity for a coach and athlete to sit down, discuss mechanics, and come to common agreement about positions and technical objectives for future training sessions.

- Compare, contrast, and discuss with other coaches around the world through common kinematic positions: As discussed, the kinogram is an easy way for coaches to “compare notes.” We sincerely hope that this method is adopted throughout the speed-power world at every level of sport—truly building a network of interactive and interested coaches seeking to better understand, teach, and improve sprint mechanics.

- Compare with other athletes from all over the world—at both the level that your athlete group is currently, and with elites from now and in the past. It’s fun for athletes to see how they match up with their friends; with others at their level around the state, country, or planet; and with elite professionals.

- Allow us to compare mechanics at different velocities, on different surfaces, with different footwear, and in different tasks within, or between, training sessions.

How to Build a Kinogram

At first, this may seem like a big undertaking, but with practice, our coaches are able to film, capture, and produce the kinogram final product in less than five minutes. It may be challenging if a coach has a group of 30 athletes, but it is important to understand that every repetition of every athlete in every session is not necessary. We attempt to build one kinogram for each athlete per week, normally during a similar training session.

Our Protocol

- First, it is important to standardize filming. We capture at high-speed video, with an iPhone set in landscape mode, from 11 meters away. It is important that the distance be consistent—too close will give subsequent frame capture parallax issues, and too far away will lead to decreased resolution. We have found that 11 meters is the appropriate distance away. We take one knee, and film from about mid-torso height. We do not pan the camera: we simply hold it level and press record just before the athlete sprints into view.

- Try to have something in the background that you can use as a frame of reference when capturing frames. We are lucky that we have a fence on either side of the outside of the track that we use. If you don’t have a fence, perhaps you can set up a few hurdles in the background.

- Once you are ready to capture your frames, pause the video and scroll to the point where the athlete is closest to the middle of the video. This is where you will want to capture your stills—closest to perpendicular to the camera.

- When you have the video paused in the appropriate section, zoom in on the video, and slide your finger or thumb across the manual scrolling slider at the bottom of the screen, to stop at the appropriate frame.

- Using the screen-capture option, capture frame stills at each of the previously mentioned positions. Following is how we recognize each position, in order:

- Toe-off: The last frame before the athlete’s support-leg foot is in contact with the ground.

- MVP: The maximal height of vertical projection, as defined by the position where both feet are parallel to the ground.

- Strike: Because of the relative difficulty in defining this position, we have determined that using the opposite leg is more efficient. The “strike” position is defined as when the opposite thigh is perpendicular to the ground.

- Touch-down: The first frame where the swing-leg foot strikes the ground.

- Full-support: The frame where the foot is directly under the pelvis—the toe of the foot should be plumb vertical with the ASIS of the pelvis.

- We then repeat this sequence for the other leg, giving us 10 still pictures in total.

- There are generally two ways to present the pictures: from left to right or in the direction the athlete is sprinting. So far, we have chosen the former, although we continue to experiment. We often see numbers placed in each frame, so that they are easier to refer to in discussions. As we only use five frames per step, and our kinograms have been internal only, we have yet to add numbers. Once we begin sharing them more widely, we will endeavor to number each picture.

- It is now time to edit the pictures so they can be consistent with each other.

- Go into your photo application edit mode, press edit, and select the “square” option.

- With the objective of having the athlete cover most of the picture, edit the picture so that the bottom of the frame is one of the track lines, and then line up a fence or hurdle in the background with one of the horizontal lines, so we have a consistent size across the group of pictures. Center the athlete in the middle of the frame.

- Repeat this step for each of the other nine pictures.

- Go through the pictures, and ensure consistency of positioning.

- Using an external application (we use PutPic), combine the pictures together in two rows of five frames, and save to your picture application.

- You are ready to check out your kinogram!

Kinogram Analysis

Following, we will offer the frame positions, key anatomical landmarks, and our expectations of athlete shapes within these positions. In addition, we have attempted to identify and comment on a few of the more frequent questions we are asked, as well as offer our thoughts on some of the sport’s more controversial subjects.

We will detail the following five frames in order:

- Toe-off

- MVP

- Strike

- Touch-down

- Full-support

We do not profess that these kinograms display “perfect” form. Rather, we chose them because of the relative similarities of the training session and the similar abilities of the athletes, as well as some of the unique differences that are evident. We encourage coaches to form their own conclusions as to where these athletes fit into their own understanding of mechanical efficiency.

Toe-Off

Toe-off is the last frame at which the rear leg (stance leg) foot is in contact with the ground.

- The stance-leg foot should be perpendicular to the ground.

- There should be a slight extension of the hip of the stance leg: The athlete should be encouraged to push vertically into the ground while they are upright sprinting. Excessive late stance-phase pushing can lead to excessive hip extension, and a stunted swing-leg recovery.

- We should see only a small amount of hip extension at toe-off.

- There should be a noticeable lack of complete extension at the knee joint of the stance leg. Over-pushing horizontally at top speed not only compromises the ground-to-air ratios, but it reduces the athlete’s vertical displacement. This means there is not enough time for the thigh to block in the correct position in front of the body; nor enough time for the lower leg to swing out and put a stretch on the hamstring and gluteal group. This causes a reduced scissoring action and a strike point underneath the COM, exacerbating the rear-side elliptical running cycle.

- We will observe an approximately 90-degree angle between the thighs.

- The toe of the swing leg should be directly vertical to the swing-leg kneecap.

- The front-leg shin will be relatively parallel with the rear-leg thigh.

- We should observe approximately 90 degrees of flexion of the foot of the swing leg.

- The forearms should be approximately perpendicular to each other.

- The rear arm should be relatively open at the elbow, while the front arm should be relatively closed.

- It is important that there is NO lumbar extension whatsoever, so no arching of the back.

Discussion Point: ‘Triple Extension’

Triple extension refers to the simultaneous extension of the ankle, knee, and hip joints. Coaches should understand, however, that complete and full triple extension rarely occurs in sprinting. On toe-off, we do not see complete extension at the knee, as the thigh moves immediately forward after this point. Furthermore, the activity of extensor muscle groups deteriorates before complete triple extension can support increased force production to contribute to speed production. Requesting triple extension from an athlete is an excellent way to promote increased ground-contact times, anteversion of the pelvis, a relatively larger back-side sprint cycle, ultimately slower velocities, and higher incidence of injury.

MVP

MVP is the point at which there is maximal vertical displacement of the center of mass, as determined by the lowest point of both feet parallel to the ground.

- Approximate 90-degree angle between thighs.

- A greater-than-110-degree knee joint at the front leg (this angle is highly independent).

- Dorsiflexion of front-leg foot.

- Fluid and relaxed throughout. It is in MVP position where we should observe maximum “peace” in the athlete (as discussed in the ALTIS keyword section of the Essentials Course).

- Neutral head carriage.

- Straight line between rear-leg knee and shoulders.

- A slight cross-body arm swing that will bring the hand towards the midline in front of the torso, and away from the midline behind the torso. This is due to the natural rotation of the spine, and is not something that should be excessively encouraged or discouraged. We will discuss this point further a little further on.

Discussion Point: Is Recovery of the Free Leg at Toe-Off Active or Passive?

Some coaches suggest that the recovery of the swing leg from back-side to front-side is a passive by-product of the forces generated at toe-off, while others propose the athlete should actively attempt to bring the leg into a position of hip flexion. It is important to understand that the recovery mechanism of the swing leg should be a very free, very fluid function. If the athlete strikes the ground appropriately, with the appropriate negative foot speed, the appropriate angle of force application, and the appropriate force, the heel will come to the buttock with the femur at zero and that transference will generally be sufficient to lift the knee.

At toe-off, the recovery mechanism of the swing leg should be a very free, very fluid function. Share on XFor example, many kids do skipping activities. They can skip all day long and their hip flexors don’t get tired, but if they do a high knee drill in which they have to think about using the hip flexors, they burn out quickly.

If the hip flexors “test weak,” it is generally due to musculoskeletal “dysfunction,” faulty enervation, neural entrapment, or antagonist inhibition, rather than what has often been described as “weakness.” Coaches are encouraged to understand this prior to prescribing any specific hip flexor strengthening protocols.

Strike

Strike is the point at which the rear-leg knee is directly vertical to the pelvis, and the femur is perpendicular to the ground. This point should correspond approximately to the first point of maximal extension at the front-leg knee joint.

- The thigh of the recovery leg will be close to perpendicular to the track, with the knee directly vertical from the pelvis.

- The “strike” is where we will observe close to maximal stretch of the front-leg hamstring—it can be compared to the point where a match head first comes into contact with the striking surface—whereas the initial ground contact at touch-down is equivalent to the flame alighting (thus the name “strike”).

- We should see approximately a 20- to 40-degree gap between the thighs. Faster athletes will have faster rotational velocity, will place greater stretch on their hamstrings at “strike” position, and will have greater reflexive contraction at stretch, and a more violent extension of the front thigh towards the ground.

- The foot of the front leg will begin to supinate in preparation for touch-down.

- The two flight-phase frames described thus far are the most variable between athletes. If coaches are interested in this further, we encourage them to consider research on attractors and fluctuators: stable and unstable components within a movement.

Discussion Point: Lower-Leg Swing and ‘Clawing’

If we simply observe the sprinting action without an understanding of the holistic nature of the way the body moves—through reflexes, co-contractions, fascial slings, etc.—we may assume that the lower-leg swing, and the concomitant pull-back towards the ground, is a volitional extension of the lower leg in front of the knee, and an active clawing of the foot towards the ground. In fact, there are many coaches who still use “pulling,” “clawing,” and “pawing” as primary sprinting cues. This is highly problematic.

It is important to understand that the out-swing of the lower leg (extension at the knee joint) is a result of the reversal of the contraction of the upper thigh (hip flexion to hip extension). Once the thigh blocks at approximately 90 degrees and starts to move backwards, the lower leg extends while the hip continues to open. The leg then comes back hard under the hip through a scissoring action, which reverses the pendulum and the cycle repeats itself. To repeat: The “casting out” of the lower leg is not a volitional action; it is simply a result of a strong reflexive action of the posterior chain extending the thigh back towards the COM.

Touch-Down

Touch-down is the point at which the front foot first contacts the ground.

- Knees together. Faster athletes, or those who push relatively more vertically, may have their swing-leg knee slightly in front of the stance-leg knee. If the swing-leg knee is excessively behind the stance-leg knee, it is normally indicative of slower velocities, weaker athletes, or over-pushing horizontally. Understand, however, that—as is the case with all positions—individual differences exist. One of the jobs of a coach is to determine when it is appropriate to make a technical change, and when it is appropriate to leave well enough alone.

A prime example here is the form of the great French sprinter Marie-José Pérec, whose positions were not in line with what we describe here. Having said that, it is important to build models based on what works for most of the people, most of the time. As coaches, we should be very careful about modeling “outlier” techniques. An example of this is in the late 1980s, when sprinters around the world tried to copy Ben Johnson’s jump start, only to find out that nobody other than Johnson himself could successfully pull it off. They lacked the necessary power abilities.As an interesting aside, while coaches have for years thought that “knees together” is an appropriate position at touch-down, this actually rarely occurs in competition. It is theorized that perhaps the increased arousal levels of the competitive arena lead to athletes over-pushing horizontally, and impede their ability to recover the swing leg in time for “knees together” at touch-down. An example of this occurred in the most recent IAAF World Championships in London 2017, when of all 16 of the 100m finalists in the women’s and men’s competitions, only one (Kelly-Ann Baptiste of Trinidad and Tobago) achieved this position at maximum velocity. All others either did not achieve this position at all, or were only able to achieve it with one leg (for example, Usain Bolt, Reece Prescod, and Yohan Blake).

- The shank of the shin should be close to perpendicular to the ground, with the heel directly underneath the knee.

- The swing-leg foot will be tucked under the gluteals, with the foot dorsiflexed.

- The hands will be approximately parallel to each other, with the elbow angles of both arms similarly open, and the hands close to the intersection of the gluteals with the hamstrings.

- Initial contact will be with the stance-leg foot slightly inverted and plantar-flexed, contacting the ground initially with the outside of the ball of the foot.

Discussion Point: Elbow Angles, Undulation, and Oscillation

It is important that all coaches understand that sprinting is a rotational-torsional activity. At toe-off (point of maximum extension at the hip), we will observe slight oscillation at the hip axis. To counteract this, we will observe similar oscillation at the shoulder axis through mid-thoracic counter-rotation. Similarly, if we watch from front or behind, we will observe counter-undulations at the hip and shoulder axes.

It is important that coaches do not try to limit these rotations in an effort to force the athlete into some sort of linear “perfection.” Our spine rotates for a reason; it is our job to make the most appropriate use of this, not to limit it unnaturally. From the side view, we should see a smooth wave-like motion of the hip, as it drops to its lowest point through late-stance full-support and rises maximally through MVP.

Understanding joints and muscle timing systems is critical to leveraging speed. Share on XUnderstanding joints and muscle timing systems is critical to leveraging speed. The human body is a hydraulic system where we have fluid in our joints. Hydraulics have a huge impact on our muscle and connective tissue systems to allow us to move greater forces.

The arms play a very important role in sprinting, and react to imbalance—so flail or compensation is always the result of something causing imbalance. If an arm is coming across the body, look at the opposite leg; arms counterbalance and help establish balance. The arms angulate from the shoulders, whereby the humerus acts like a pendulum; therefore, tension in the shoulders should be avoided as it impacts the oscillation of this pendular action.

The elbow joint should angulate through the swing commensurate with the knee joint. Rigid arm angles mean rotation shifts towards lumbar joints, which are better designed for flexion and extension than rotation. Many low back problems can be sourced to the relationship between the hip and shoulder axes undulating and oscillating with one another. We cannot stress enough the importance of allowing the elbow joint to open as the hands pass by the hip at touch-down. The arms will naturally close in front of and behind the body, so we will not need to cue this with most athletes.

Full-Support

Full-support is the point at which the stance-leg foot is directly under the pelvis, as indicated by the great toe approximately vertical to the front of the pelvis, and the heel approximately vertical to the rear of the pelvis.

- The swing-leg foot will continue to be tucked underneath the gluteals, with the foot fully dorsiflexed.

- The swing-leg thigh will swing in front of the hip to form a “figure four” position in relation to the stance leg. The swing-leg thigh will be approximately 45 degrees relative to perpendicular.

- Lower-body stance-leg amortization (yielding) should be consistent from the left to right leg. There will be relatively more yielding at the ankle joint than there will be at the knee and hip joints.

- Excessive yielding can manifest from a lack of specific strength abilities, a relatively more horizontal application of force, or initial touch-down too far in front of the COM. Understanding amortization factors should be of paramount importance for all coaches, as not only does it affect how we ask athletes to move, but also what we ask them to do. For example, over-yielding at the ankle joint may be a mechanical issue or a strength issue; the good coach will understand both the problem (e.g., weak posterior lower-leg musculature) and the appropriate input (e.g., strengthening of the lower-leg musculature).

- The stance-leg knee will yield slightly from touch-down. The degree of yielding is specific to the level of the athlete. The best athletes in the world will yield significantly less than their slower counterparts.

- The stance-leg foot will roll from outside to in (pronation), with all toes coming into contact with the ground.

- The foot will continue to pronate through full-support and into toe-off, with the great toe being the last point of contact. If the great toe does not flex appropriately, and/or if there is a bunion, we may see excessive pronation and a concomitant “whipping” motion of the lower leg (observing from behind). If we observe this, it is imperative that we normalize function of the great toe; otherwise it will compromise effective mechanics and athlete health.

Discussion Point: Dorsiflexion

How the foot contacts the floor is also critical. One of the greatest myths in sprinting at the high school level is that athletes should “get up on their toes” at high speed, or “run on their toes.” This is simply not what happens, and is a teaching concept that coaches should never utilize.

It is a high school level sprinting myth that athletes should ‘get up on their toes’ at high speed. Share on XWhile it is important that athletes understand the importance of a stable foot and ankle, we will always plantar flex prior to touch-down. Plantar flexion just prior to ground contact is a reflexive action that intensifies as velocity increases, so we will never observe a dorsiflexed touch-down during a maximum intensity sprint. Having said that, for athletes who over-plantar flex, and contact the ground too far in front of the COM, cueing dorsiflexion earlier in the sprint cycle can have a positive effect, though rarely is it the sole culprit.

Understand that what we do while on the ground will determine, for the most part, what happens while we are in the air. If the athlete over-pushes out of the back side, it will set up a relatively more horizontal parabola, excessive plantar flexion on the front side, and early touch-down. If you see a big rear-side “butt kick” and no knee lift, it generally means the athlete doesn’t understand pathways and ground contact time. Excessive plantar flexion during the back-side cycle, and spending too much time on the ground behind the COM, causes this.

Many question as to whether dorsiflexion needs to be taught in the running cycle. Athletes who experience negative interference from previous activities will suffer if they strike the ground excessively plantar-flexed, or complete the running cycle in a plantar-flexed position. In this case, the foot will collapse upon touch-down at a radical rate, and amortization rates during the early-stance phase will be significantly faster than if the ankle and the foot are stiffer.

When we observe elite sprinters, we tend to see relatively closed angles at the ankle joint inches away from ground contact prior to the reflexive opening. So, for athletes who have negative transference from other sports (gymnasts, for example), cueing dorsiflexion may be critical: it reduces injury, shortens lever systems, and promotes healthy joint hydraulics, and timing.

Exercises designed to strengthen the front of the shins are not appropriate at any time. Share on XUnderstand also that the inability to dorsiflex is rarely due to a lack of strength of the plantar flexors; thus, exercises designed to strengthen the front of the shins are not appropriate at any time, and will generally lead to more problems than they solve. Instead, coaches are advised to measure the passive range of motion at the ankle joint, and ensure that the athlete even has the ability to dorsiflex in the first place. If the passive ROM is not sufficient, then this needs to be addressed before any dorsiflexion cue can take effect.

Global Kinogram

- Neutral head carriage, with eyes looking directly ahead. The human body is an inverted pendulum subject to imbalance through improper head position, and that impacts weight distribution further down the chain. Therefore, if the head is out of position, there will be an impact in lower-body joint dynamics. Athletes who throw their head back or push their chin forward create imbalanced forces. In the upright running cycle, the head should be held in neutral alignment with the cervical spine. Understand that any deviation from this will also negatively affect lumbar vertebrae position, and possibly pelvic alignment.

- The pelvis should remain neutral throughout the cycle. This is most-negatively affected by over-pushing out of the back-side, placing excessive stretch on the flexors of the hip to stabilize the pelvis, excessive flexion at the lumbar vertebrae, and a concomitant anteversion of the pelvis. This is perhaps the single greatest technical error we see, from young athletes all the way up to elite professionals.

- A lack of stiffness and control in the lumbopelvic region is also sub-optimal, as forces cannot be transferred optimally upon ground contact through the storage and return of elastic energy. Maintenance of a braced trunk and the ability to do this at speed is therefore an important consideration. The point of ground-strike relative to the pelvis and the angle, and force application at which they’re striking the ground, has huge ramifications on pelvic posture. If an athlete strikes the ground a little posterior, there’s a greater tendency to have anteversion of the hips; if the strike is too far out in front, the hips have a tendency to move into retroversion, and vice versa.

- Relaxed hands. It is not especially important whether the hands are closed or open—just that they carry no tension. We will often even observe sprinters who accelerate with hands closed, and open them as they begin to stand up through the course of the sprint (or vice versa). This is something that should be left to the discretion of the athlete. Encourage them to try both, and go with the one that feels most comfortable: i.e., the one where there is less tension.

- Slight forward lean of the torso (though this should rarely need to be cued).

- We should only observe tension in the muscles that are active at the particular point in time. Excessive tension in non-active movers will only lead to compromised performance.

Discussion Point: Posture

This term refers to both the static and functional relationships between body parts, and the body as a whole. The concept includes over 200 bones and some 600 muscles, not to mention the endless chains of fascia and various connective tissue systems. Efficient body mechanics is a function of balance and poise of the body in all positions possible—including standing, lying, sitting, during movements, and in a variety of mediums. These systems are monitored, driven, and controlled by a complex network of proprioceptors and their related members.

These functions can be further evaluated by observing excessive stress on joints, connective tissue, muscles, and coordinative action. In the sport of track and field, “active alerted posture” is the goal of all sportsmen. This can be defined by the balanced action of muscle groups on both sides of body joints at six levels:

- Ankle joints

- Knee joints

- Hip joints

- Lower back

- Head and neck

- Shoulder girdle

People often try to design training schemes for posture of the spinal column, head, and pelvis in static routines in which they’re stationary. We see athletes doing incredible balance work in a pretty stationary motif and they look world-class, but when they run down the track, these different postural landmarks just don’t hold up. Posture at speed is very dynamic and involves complex communication between the body’s systems that is difficult to replicate in the weight room.

Some Case Study Examples

Once we understand the expectations of each of the positions, as well as how and/or when these positions can be compromised, we can begin to identify ways in which kinograms can be used over and above simple single-run analysis. As previously discussed in the justifications section, there are a multitude of different ways we can use the kinograms. While each coach should use methods that are most appropriate for the time, circumstance, and athlete population they work with, we will provide a few examples here of how we have used them in our own practice.

Asymmetries

Left-right asymmetries are easily identified in the above kinogram. We see in the upper frames that the swing-leg foot is significantly further behind the swing-leg knee at toe-off, for example. This gives us a starting place to attempt to identify why this is so.

Discussion Point: Symmetry

The body craves symmetry. If we observe asymmetry, it is almost always due to a musculoskeletal issue—rather than a technical “mistake” on the part of the athlete. If we identify an asymmetry, it is prudent for the coach to attempt to understand why it is evident, rather than try to cue the athlete out of it. If we identify, for example, that one side of the body has a tight hip flexor relative to the other side of the body (which is evident in the above kinogram), then we can prescribe additional stretching or a therapeutic intervention. This is a far more appropriate reaction to an asymmetry than asking the athlete to focus on one side over the other, which will generally just add fuel to the fire.

Athletes are great compensators—the superior ones compensate better than the less superior—so it is often very difficult to identify the driver of any musculoskeletal discrepancy. This is a challenge that we can only address through consistently and attentively analyzing movement.

The key to keeping athletes healthy is understanding the reasons their movements may be abnormal. Share on XWatch your athlete-group closely. Watch as many videos as you can get your hands on. Build out your kinograms, and share with others. Eventually, we will all become better at not only analyzing movement, but understanding the reasons why movement may be abnormal. This is truly the key to keeping athletes healthy!

Progression over Time

On the bottom kinogram above, we can see that the athlete is over-pushing out the back—spending a little too long on the ground behind the COM.

The athlete was asked to work on pushing more vertically—bouncing down the track, rather than pushing horizontally—and in warm-up wicket runs to slightly over-exaggerate this feeling. Thus, we see the upper kinogram, where the athlete has pushed overly vertical, and ends up with the free-leg foot significantly in front of the free-leg knee at toe-off. This position has, however, set up a greater hamstring stretch at “strike,” an increased rotational velocity, and a more appropriate touch-down relative to the bottom kinogram.

Intra-Group Comparisons

The above kinogram shows the similarities between two elite sprinters (PRs of 9.91 and 9.94). There are far more similarities between all these frames than there are differences, which highlights not only common positions and solutions, but also a common technical model.

Discussion Point: ‘Modeling’ Technique

Over time, all athletes will develop their own individual, idiosyncratic movement solutions. Generally, however, the closer an individual solution is to the most-efficient mechanical model, the better the athlete will be. The best athletes in any sport will almost always have a solid grounding in fundamental techniques.

It is important to understand, though, that individual differences do exist. One of a coach’s jobs is to determine if this difference is significant enough that we should step in and attempt to make a technical tweak, to close the gap to the more “appropriate” model. There is no doubt that this is a multi-layered, complex decision to make.

Following are a few heuristics to help us decide:

- If the athlete is young (i.e., still growing), then we source the root of the discrepancy, and attempt to make the change.

- If the individual solution is asymmetrical, this should not be addressed through a technical tweak. Rather, we need to understand the source of the asymmetry, and address that.

- If the individual solution is so far off the most-efficient mechanical model that it is having negative effects on athlete health, then we source the root of the discrepancy, and attempt to make the change.

“Mechanics are the heart of every legit/complete S&C program. Fitness, strength, power, etc. are all SIDE effects.” –Dr. Kelly Starrett

Task Variance

The kinogram below compares an athlete executing two different sprinting tasks.

The upper kinogram shows the athlete sprinting off the end of a 220-centimeter wicket lane, while the lower kinogram shows two consecutive steps at the beginning of the straight-away at the end of a 60-meter end-bend run. (The first step begins 10 meters off the end of the bend.)

The purpose of this comparison is to see how stable the model is by comparing the potentiating, more controlled task to a more race-specific task.

Historical Perspectives

It’s sometimes fun to go back in time, and see how athletes from previous generations sprinted. Above, we see the five-frame kinogram for Carmelita Jeter. We have drawn lines over it to more easily depict and measure the angles, if we wanted to analyze it further.

Historical Outliers

Donovan Bailey

1996 Olympic Champion Donovan Bailey seemed to “gallop” down the track, especially when he was at maximum velocity. In the kinogram above, you can clearly identify significant asymmetries. In fact, Bailey had a significant anthropometric abnormality, so expecting symmetry would have been a fool’s errand.

Marie-José Pérec

As discussed previously, French sprinter Pérec had an extremely unique stride: long, and relatively back-side dominant. Nevertheless, she enjoyed great success. Above, we also see the difference between Pérec’s stride in the 100m (upper kinogram) and the 200m (lower kinogram).

Jesse Owens

Notice the short arm carriage of Owens, and relatively choppy stride. Michael Johnson adopted this a few generations later.

An Optional Kinogram Series for Those Short on Time

An optional kinogram series for those with less time can be based on the only two attractors during the gait cycle: touch-down and toe-off. All other positions may be predicted from these two frames.

Dr. Nick Winkelman, motor learning expert and Head of Athletic Performance & Science for Irish Rugby, offers an interesting alternative that relates to the relative angle of projection:

The question of appropriate selection of frames as it relates to prioritization and simplicity, “is to identify the lowest number of technical landmarks that, if changed, have the largest impact on the entire technique; therefore: 1) toe-off, and 2) full-support. Interestingly, toe-off precedes the primary horizontal change in force-motion (i.e., back to front) and full-support precedes the primary vertical change in force-motion (i.e., down to up). I feel that these force-motion shifts (i.e., eccentric to concentric) carry the variability that echoes through the coordination that connects these space-time points. Thus, good coaching can be directed at these time points, with physical development working on the neuromuscular factors that need to deliver the coordinative message.”

Below is what the kinogram would look like if we followed Dr. Winkelman’s recommendation. It is certainly something to consider.

Additionally,a two-frame kinogram may be a better way to capture acceleration mechanics.

Coaches with less time can base an optional kinogram series on the touch-down and toe-off. Share on XWe use this method to capture projection and rise elements of the acceleration, compare them across time, and even compare them across varying external loads, as shown below.

This kinogram shows a sprinter accelerating out of the blocks with the equivalent of 40%, 20%, and 3% of additional body-weight in resistance—using the 1080 Sprint machine. This kinogram was an effective and efficient way for us to track any mechanical changes with the additional external load.

The Value of Kinograms

We hope you have found this article valuable. Whether you coach football players, softball players, or sprinters, we also hope you will enjoy the kinogram process, and the insight this can give you into the mechanics of the athletes you coach. Please share these kinograms online, through your social media channel of choice (tag @ALTIS), as well as on the ALTIS Agora Facebook page. We look forward to continued discussions around efficient sprint technique, and the impact effective mechanics can have both on performance and health.

Be sure to check out the new ALTIS Essentials Course!

The authors would like to thank Drs. Nick Winkelman, JB Morin, and Ken Clark for their input, and especially PJ Vazel for the wealth of information he continues to provide.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

[mashshare]

Coach Dan Pfaff is a globally recognized expert in the field of coaching and coach education. With more than 40 years coaching across multiple track & field disciplines, Dan has led 49 Olympians to nine medals. He has lectured in 27 countries and consults across multiple sports, delivering coach education to national governing bodies and private organizations globally, in sports ranging from football and basketball to rugby, soccer, golf, and baseball.

Coach Dan Pfaff is a globally recognized expert in the field of coaching and coach education. With more than 40 years coaching across multiple track & field disciplines, Dan has led 49 Olympians to nine medals. He has lectured in 27 countries and consults across multiple sports, delivering coach education to national governing bodies and private organizations globally, in sports ranging from football and basketball to rugby, soccer, golf, and baseball.

3 comments

Eve

Looks like the work precaunized by the French international coach J. Piasenta (coach of MJ Perec) during the 1980 years.

During this time there was always opposition between the technical way and the natural way among coach.

Interesting

Nathan Irvin, CSCS, USATFII

Really enjoyed this post. Dan, I’ve had a copy of your training inventory for about 24 years, after an olympic trials level triple jumper passed it along to my brother who then passed it to me. Between that, and falling in love with Donovan Bailey as the surprise winner in 96, I’ve been a fan of yours and your cerebral approach to sprinting and the mechanics behind it. I’ve always felt that analysis of gait was something left to the pros with expensive equipment, but knowing it is now easily done with an iPhone is encouraging! Very helpful to understand best practices in setting it up as well.

I am also a huge proponent of root caused based approaches to coaching , and under-cueing an athlete rather than over-cueing. Also nice to see recommendations around what to cue and what not to.

One question, during the touch-down phase and the differences noticed between competition and practice, have the actual maximum velocities been measured and seen to also be slower in competition compared to the proper “technical” execution in practice? Or has the adrenaline of competition still allowed the athlete to overcome the technical deficiencies at race time. I’ve always personally had an issue “relaxing” enough at competition and have always suspected I’ve hit faster max velocities in practice. I have always trained alone so I can not measure.

Thanks again!

giorgio

Why not invite readers to collect as many kinograms as possible from various eras and athletes (eg Sime, Murchison, Morrow, Berruti, Rudolf, Tommie Smith, Borzov, Tyus, Juantorena), and send them to Simplifaster?