We have all mindlessly scrolled through our Instagram, Twitter, or Tik Tok and come across “sport specific” exercises posted by a fitness influencer. Some of these exercises or methods posted might have some value, but there is a subset that are over the top and utterly ridiculous. Think of a basketball player standing on a Bosu ball while dribbling and claiming to be working on balance or an athlete Icky-shuffling through an agility ladder and saying they are working on speed. These exercises, of course, would have no transfer to balance or speed relating to their sports—it is simply eyewash that delivers zero transfer.

The social media landscape is a great place for coaches to share ideas and interact with each other, so by no means am I suggesting social media is bad. But, with that being said, when scrolling through those platforms, be wary of nonsense and exercises that could have no potential transfer to the athletes’ sport. When laying the foundation for an athlete’s training, coaches often follow the principle of general to specific. This poses two simple questions;

- What is general?

- What is specific?

This article will aim to clear the murky water and guide you on this road of general and specific preparation, focusing on specific methods to train acceleration and horizontal force production.

What is Specific?

General training should eventually bleed into more specific training for more advanced athletes. This leads us to the question of what even is specific training? What classifies as a specific exercise? When should this shift even occur?

Specific training, in my opinion, is taking a characteristic of sport or competition and replicating some aspect of it in training. For example, we know that acceleration has a horizontal direction of force component, so we may find exercises that promote horizontal force output.

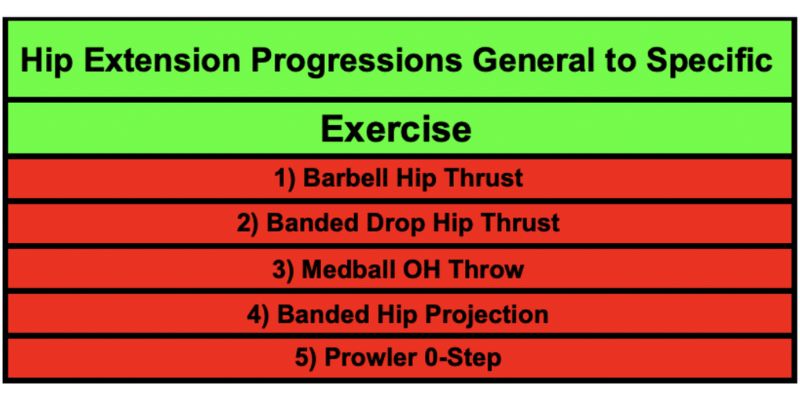

Video 1. Hip extension progression and regression.

In their book Supertraining, Yuri Verkhoshansky and Mel Siff describe the concept of dynamic correspondence as a term used to describe the transfer of exercise. The principles that make up dynamic correspondence are:

- Amplitude and direction of movement.

- Accentuated region of force production.

- Dynamics of effort.

- Rate and time of force production.

- Regime of muscular work.

These principles are surely valid, but I think there are some other factors that should be considered when looking to program specific exercises. For example, ground contact time (GCT), horizontal or vertical force application, and power output, just to name a few.

As stated earlier, we just want to take some characteristics of sport and try to implement this into our training. Let’s take a look at acceleration, for example, since acceleration is present in nearly every sport. Some key components of acceleration are:

- Hip extension.

- Horizontal force output.

- Concentric muscle action upon zero-step.

- Ground contact times that range around .25 seconds.

With these factors in mind, we can select exercises to target these qualities of acceleration. As we get closer to sport we want exercises that promote aggressive hip extension (as shown in the hip extension progression/regression video). Early on in an athlete’s off-season training, we may use lifts like trap bar deadlift, barbell back squat, or other bilateral/unilateral variations. But as we get closer to sport, we will want a stimulus that is more ballistic (higher velocity movement) and on an acceleration focused day we will want something with a horizontal focus.

As we get closer to sport, we will want a stimulus that is more ballistic (higher velocity movement) and on an acceleration focused day we will want something with a horizontal focus, says @nolan_dreh99835. Share on XVideo 2. Example of a French Contrast variation that can be implemented closer to competition.

This is where tools like the prowler, SHREDmill, and Optimal Human Motion (OHM) have been so useful.

Video 3. Exercises that transfer to acceleration using the prowler, SHREDMILL, and Optimal Human Motion.

These tools allow us to train horizontal strength at higher velocity than vertical weightroom movements like traditional squats and deadlift variations, while being able to work on technical qualities of acceleration! I am not saying that squats and deadlift lifts do not have value. I think those lifts provide a great way to get stronger and make structural changes, but eventually we need to put force in a horizontal manner.

Many of the athletes that we train are great at producing force vertically, but they lack the ability to translate that force horizontally (hence shifting training emphasis to be more specific in a horizontal manner!). There can be various reasons for this: lack of limb velocity to switch efficiently (which presents as the athlete striking straight down into the ground instead of being able to reposition the limb and whip it back into the ground), energy leaks in the lower limb, and even tight hips from too much squatting.

Many of the athletes that we train are great at producing force vertically, but they lack the ability to translate that force horizontally, says @nolan_dreh99835. Share on X

Next, let’s look at the zero-step in acceleration—this is characterized by going from a static to a dynamic position (concentric muscle action). Again, you may start with exercises that are more vertical in nature, such as isometric squats, isometric deadlifts, and non-counter-movement jumps. The next transition would be to use exercises that are more horizontal. You can also set the athlete up in specific angles to mimic the horizontal force vector they would experience. Below are examples of two exercises that mimic the vector of a block start for a track sprinter—obviously, you can set the athlete up in the most specific position possible for their sport.

Video 4. Example of an acceleration-specific tri-set aimed at improving force, power, and technical abilities in the block start.

The overcoming block start will yield high force directed in a horizontal manner, while the horizontal banded block start will yield more power due to the higher velocity—thus, allowing you to surf the force-velocity curve. Following these exercises up with a free block start can aid in the transfer of the other exercises, as the athlete is now able to apply selected cues and skills from the other exercises and apply it to their actual skill (in this case, the block start).

Ground contact time (GCT) was another consideration. We know that in acceleration, our ground contact times are longer than at top speeds. We can now look at our plyometrics in a more specific manner with regards to GCT. If we know that the first few steps in acceleration are around .25 seconds, we can find plyometrics that eclipse or equal that GCT.

Hurdle hops are a common plyometric that coaches will implement—I think hurdle hops are great, but the height needs to be considered. If hurdles are set too high, some athletes will deform (not remain elastic) and spend too much time on the ground. The exercise then turns into something completely different, no longer working the elastic qualities we want to target. With technology like Swift EZEJUMP mat, we are able to get valuable data like GCT to make decisions on the height of hurdles or boxes.

Further consideration can also be made in regards to joint angles: typically, higher hurdles and horizontal jump variations are going to yield deeper joint angles.

Video 5. Drop to broad jump with jump mat to track GCT.

Methods to Implement Specific Training Means

All of this information is great…but how is this practically applied to a training session? There are various methods that can be used. Two of my favorites are French Contrast and performance patterning, both popularized by Cal Dietz. These two methods allow the force-velocity curve to be surfed, and the performance patterning allows a balanced approach to the posterior chain by building the posterior-focused exercises into the sequence with the anterior-dominant exercises.

Video 6. Horizontal-focused performance patterning for acceleration deficient athlete—exercises in this method are designed to transfer to an athlete’s acceleration.

The other benefit of these methods is the alactic repeatability, with the athlete being conditioned to constantly produce high force and power outputs. I use the French Contrast method before going into the performance patterning, purely from the standpoint of the added in-set volume. Of course, the athlete should have a solid foundation of general preparedness built up before engaging in these more specific training means to reap the full benefits.

These methods are very flexible and coaches can get very creative and begin to work different movement patterns. Below you’ll see an example of a lateral emphasis French Contrast that we would use closer to competition for a field, court, or ice-based athlete.

Video 7. French Contrast sequence in the frontal plane for an athlete close to competition.

Hopefully, you can now see how in-depth prescribing specific training can get. Remember, we just very simply broke down acceleration and a couple of its characteristics and tailored exercises to be more specific to aid in improving acceleration. You can do this with a lot of skills present in sports—just understand the level of athlete you are working with and their deficiencies.

What is General?

Having first jumped ahead to specific preparation, now let’s backtrack—general preparation is designed to uplift general qualities. When I reference general qualities I am referring to strength, power, speed, and conditioning. The whole purpose of training general qualities is to support the specific skills you need to succeed in your sport.

Putting this into context, an offensive lineman in American football would want to increase their strength to be able to support their skill of blocking a defensive lineman. The word support is key in this context. As physical preparation coaches, we need to understand the tactical and technical sides of sport are what determine success—just being strong or fast is not enough. An offensive lineman could bench one thousand pounds, but if he doesn’t have the skill to kick-step, position hands, or be physical at the point of attack it does not matter: they will not be successful in the game, no matter how strong they get.

What does general preparation look like and how should it be implemented? General preparation should look “general” for lack of a better term. In terms of the weightroom, movements should be basic in nature; squat, hinge, push, pull, and rotate. Consider this the foundation of your house. The bigger the foundation, the more potential room to support the specific skills of your sport.

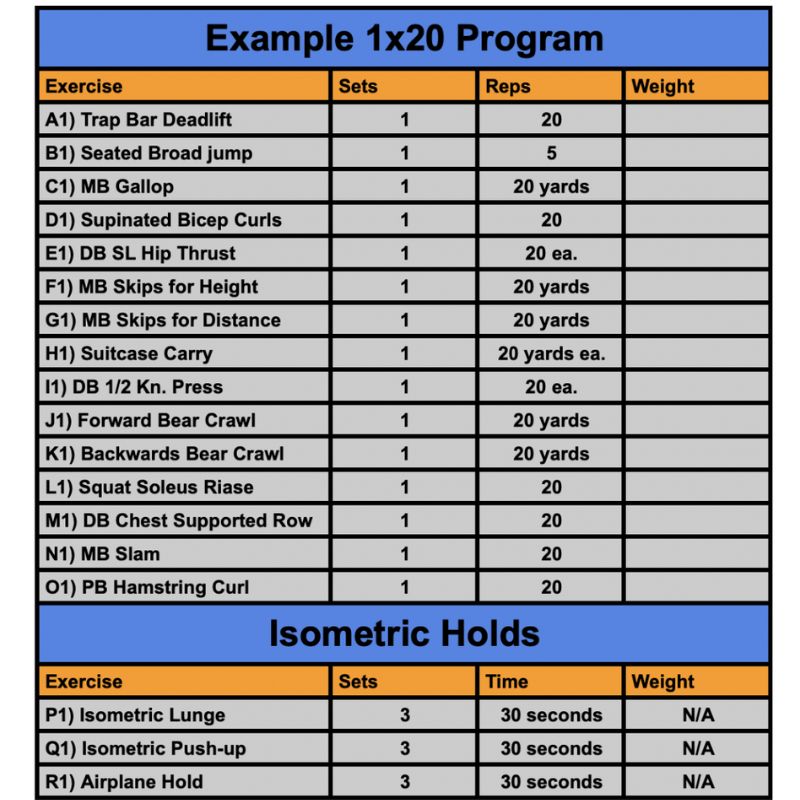

When it comes to implementing general training, there are some methods I like to use. Dr. Michael Yessis' 1x20 program is a great way to keep training extremely simple, says @nolan_dreh99835. Share on XWhen it comes to implementing general training, there are some methods I like to use. Dr. Michael Yessis’ 1×20 program is a great way to keep training extremely simple. The 1×20 program is an effective method for athletes with a young training age for a couple reasons:

- It exposes athletes to various different movements: hinge, squat, etc.

- The idea of progressive overload and trying to get the most adaptation out of one set is an interesting idea for athletes with a young training age.

When implementing the 1×20, you will begin to realize less is truly more! Athletes with a young training age that begin resistance training will see gains in strength, power, and speed relatively fast with simple progressive overload.

With this population, advanced methods are not needed to continue to see strength, power, and speed gains. There is no need to perform exercises with accommodating resistance or other special means. Keep it as general as possible for athletes with a young training age, allowing them to grow with the basic exercises before advancing to more specific training means. There is no need to throw novice trained athletes into advanced methods early on, as you are robbing them of their future development by using the higher intensity methods too soon.

We have also used the 1×20 method with our older athletes who are typically used to higher-intensity programming. This allows for less stress to be applied in the weightroom, which in return has helped performance gains in terms of acceleration, max velocity, and agility. This is critical, because in terms of an athlete’s career, specific improvements in qualities that will directly carry over to the field are more important. For example, if an American football player can squat 400 plus pounds, should their training continue to be tailored towards strength? In my opinion, the answer is “probably not.” Yes, the quality of strength should be touched, but it should not be a sole focus. So, 1×20 could be used as a maintenance program to preserve strength while shifting more of the stress and focus to field-based performance (acceleration, max velocity, and change of direction).

No matter what method you choose, hopefully you realize that general training is not trying to replicate anything specific from sport, but is instead keeping it simple. Hopefully this article helped show you how to dissect movements and practically apply exercises and methods to yield the results you desire.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF