Most of us have heard of the French Contrast method, popularized by Cal Dietz. For those unfamiliar, the method is composed of a heavy compound movement, an unweighted plyometric, a weighted plyometric, and an assisted plyometric, using post-activation potentiation (or PAP) to increase power and speed.

The French Contrast method creates an environment for repeated power outputs, which is great when it comes to repeat sprint ability for team sport athletes. Energy system development is critical for all athletes, and all energy systems are present at all times. Team sports are typically won on big powerful plays (breakaways from defenders, closing distances, and quick bursts of acceleration/deceleration).

We are looking to train the ATP-CP system—our “fast twitch,” in layman’s terms. It is important to remember we are training max effort outputs, so sufficient rest between reps is critical. Here at Total Athlete Performance (TAP), we use the model of one minute of rest for every 10 yards sprinted. The options are seemingly endless for whatever movements you select.

Sprint Contrast, modeled in the same format as French Contrast, is a method we love for repeat sprint ability and speed development. Share on XThese “seemingly endless” opportunities have led us to think outside the box when it comes to sprint training. Sprint Contrast, modeled in the same format as French Contrast, is a method we love for repeat sprint ability and speed development. We’ve implemented this as a heavy resisted sprint, vector-specific unweighted plyometrics, resisted sprint, and acceleration or fly. (This model is, of course, subject to change.)

As coaches, we should understand when to implement a method like this, taking into consideration the level of the athlete, time of year, and current condition of the athlete(s) you work with. This is not just something to throw your athletes into—there should be a period of build-up on technical qualities along with physiological qualities. We like using this method in preparation for peaking our athletes because it lays a solid foundation for enhancing qualities of power and repeat sprint ability.

How It Works

The way we went about using this method was simple. If we look at a five-day training plan (Monday–Friday), Monday is acceleration-based, Wednesday is max velocity focus, and Friday is a change of direction and agility-focused day. We used this method on Monday and Wednesday, which were our linear sprint-focused days.

When programming speed, we use load-velocity profiling (LVP), which allows us to select a load that will bring that athlete’s sprinting velocity down to a certain velocity. For example, if an athlete who runs a 1.02 10-yard fly (20 mph) does a sprint with a sled—and that sled reduces his speed to 10 mph—we now know that the load on that sled reduces the athlete’s velocity by 50% (10 mph).

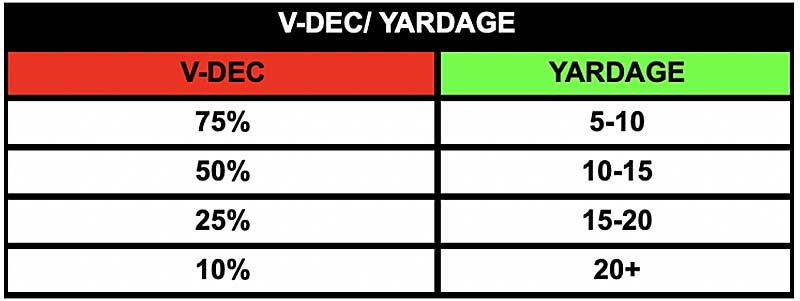

Depending on the quality we want to train, we will use a velocity decrement that correlates to that quality. For example, with an athlete who struggles in early acceleration, we would choose a heavier V-DEC (velocity decrement), from 50% to 75%. We use these loading parameters to attack certain sprinting qualities:

- 75%+ starting strength

- 40%–60% power

- 10%–40% speed strength (late acceleration)

- 10% technical competency

When implementing these heavier loads for resisted sprinting, it is important to take yardage into consideration. It is unrealistic to expect someone to sprint with a 75% velocity decrement past 10 yards.

When implementing these heavier loads for resisted sprinting, you must take yardage into consideration. It’s unrealistic to expect someone to sprint with a 75% velocity decrement past 10 yards. Share on X

With our loading and quality parameters covered, let’s dive into the method and exercise selection we used.

The SHREDmill—a self-propelled, non-curved, non-motorized treadmill—is an effective tool for working early acceleration, from both a stimulus and a technical perspective. The SHREDmill is particularly great from a switching aspect.

Video 1. A key performance indicator for us is the ability to switch from the hip, which can be developed in training with a SHREDmill.

On our acceleration day, our first exercise was a SHREDmill Gear 1 sprint. The belt gives instant feedback on the athlete’s ability to switch from the hip. Gear 1 on the SHREDmill is heavy, typically a 40%–60% V-DEC, depending on how technically sound the athlete is. If you do not have a SHREDmill, it’s okay! You can also use a heavy sled.

Video 2. We typically cue “open up” (big thigh splits), “attack back,” and “away.”

The second movement we chose was a horizontal hurdle hop into a broad jump. This plyometric allows us to keep consistency with our direction of force in the horizontal vector. Any sort of horizontal plyometric is fine.

Video 3. Space out hurdles a little further than your typical hurdle hop. We do not want an extended ground contact into the broad jump.

Our third movement (weighted plyometric) was a 30% V-DEC sprint on the Run Rocket (or sled) for 10 yards. Again, here we just want to enhance the neural drive right before the exposure of the 5/10 or 10/20 acceleration.

Video 4. We typically cue our athletes on acceleration days to be “violent at the start.”

Finally, the athlete would run the 5/10 or 10/20 acceleration. We have seen a lot of athletes set personal records because of the huge potentiation effect. Coaches need to be sure to keep the yardage and volume low in resisted sprints and plyometrics to not overcook the steak before the lasered sprint time.

Video 5. Using laser timers gives us instant feedback on each sprint while also upping athlete intent.

We used this concept on our max velocity day as well. Our thought process on applying this concept was slightly different. We understand that max velocity sprinting is the fastest plyometric that we can do. Keeping that in mind, our potentiation ideas were slightly different.

There is a fine line between cooking the steak and potentiating an athlete. Max velocity sprinting is very neurologically demanding, so we do not want to bog the system down with heavy resisted sprints before a longer sprint at top speed. Instead, we used an overspeed movement.

Max velocity sprinting is very neurologically demanding, so we don’t want to bog the system down with heavy resisted sprints before a longer sprint at top speed. We use an overspeed movement instead. Share on XOverspeed movements force athletes to switch and exchange their limbs faster than they could manually. Our athletes seem to feel “supercharged,” as if it has some sort of neurological potentiation effect. Our overarching theme of building repeat sprint ability is still intact, with the athlete still being tasked with delivering high power outputs at an even higher velocity. This differs from our acceleration days, which are filled with short bursts of heavier loads at lower velocities and are more “power” based.

Our first movement on this day was a 15-yard Run Rocket sprint at a 25% V-DEC, trying again to enhance the neural drive and potentiate the athlete.

Video 6. We like to cue “attack the first 10 yards,” then start to transition.

Next was a high double hurdle hop. Staying with our theme of a vector-specific plyometric, we wanted a plyometric with a more vertical orientation of force.

Video 7. We encourage our athletes to spend little time on the ground.

The third movement we selected was an assisted primetime. Essentially, we want the athlete to feel what it’s like to switch fast from the hip, similar to our aim with the SHREDmill. The ability to switch and exchange our limbs is a KPI (key performance indicator) in both acceleration and max velocity sprinting.

The overspeed stimulus is a great potentiator before running at max velocity. Note that we only do this with higher-level athletes who can handle the stimulus. For our younger athletes, we used a trampoline RFI (reflexive firing isometric) sprint. The trampoline provides a similar stimulus in the manner that the athlete has to switch faster because of the reflexive nature of the trampoline. It also allows us to focus on positioning, timing, and rhythm.

Video 8. This is a movement that we only use with our more advanced athletes.

Video 9. Positioning cues we use for this movement are: “be tall,” “lift front-side” (A-position), and “switch hard and fast.”

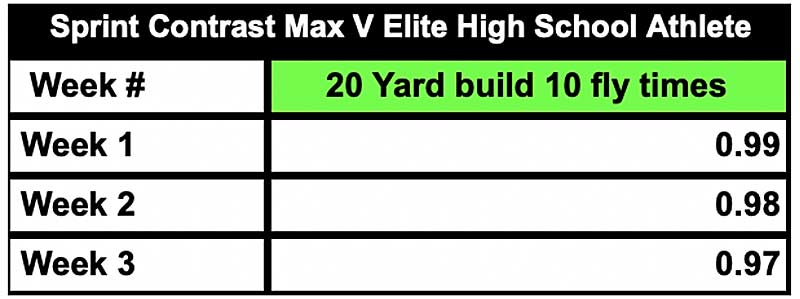

Finally, the athlete would run the 20-yard build 10-fly. Just like on our acceleration days, we saw a lot of our athletes set personal bests.

Video 10. We like to remind our athletes to relax and feel smooth, not to fight for a personal best.

Results on RSA

When thinking about team sports and the demands on athletes, repeat sprint ability is paramount. The ability to repeat and produce power over and over is essential, making this method optimal for team sport athletes.

As you can tell, this particular athlete set personal bests on his 20-yard build 10 fly three weeks in a row. He increased his top speed window (speed reserve has grown), while also increasing his ability to repeat short bursts of acceleration.

Note that this is just a method, not a training principle. Stick to what makes sense for your athletes. But we’ve used the method here at TAP and seen good results with it.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

Fair to say this could be replicated replacing the SHREDmill with a hill, yes?

– 1/11/2024