Imagine you’re walking into a store with a list in your hand, determined to get out as fast as possible. You don’t want any distractions or impulse buys to take up your time or money—but right as you hit the first aisle, a uniform-clad employee shoves a pamphlet in your face. Agitated, you furrow your eyebrows and glance at it quickly: How dare they try and upsell me! I know what I need. And then you realize smack dab on the front page are all the things you came there for, with coupons to cut your bill way down.

In our haste, we sometimes ignore all of the ads and discounts around us because we have a “mission.” In our hurried state, we become like Goldilocks, who ignored the warning signs and tried to get a good meal and bed, but was set on fire and eaten by anthropomorphic bears instead (according to the 1831 version of the story, and I promise I have a reason for bringing this up).

Post-activation potentiation (PAP) takes the training we would already do and gets us the results we want, faster, says @endunamoo_sc. Share on XAs coaches, we can be unwilling to realize our mission has put us in a bear’s den when a great opportunity for nourishment and recovery lies elsewhere. That’s how I like to look at the training phenomenon known as post-activation potentiation (PAP). Many of us are so focused on certain aspects of our training—such as optimal squat depth or whether we should use a trap bar—that we aren’t experimenting with a system that affects the real reason we train athletes: getting faster and more powerful. PAP takes the training we would already do and gets us the results we want, faster.

You’re Doing What to My Potentiation?

We’ve all had good days, bad days, and just plain okay days. Too hot, too cold…and sometimes just right, whether that be in the gym or just life in general. As you get older and wiser, you learn how to turn bad days into okay ones, and okay days into great ones. You can apply the same principle to training athletes. By manipulating things like warm-ups, exercise selection, and even intensities, we can create a “sweet spot” that maximizes the output that someone has available for that day.

PAP is a theory that prior activity can positively impact the performance of subsequent movements. Many coaches have already heard of this theory, but a layperson might ask, “Wouldn’t doing more activity make you tired?” After all, nobody ran a marathon and then magically dunked for the first time. The answer to your/my/their hypothetical question is, “It depends.”

Fatiguing muscle activity can decrease performance—however, stimulating contractions can enhance it. This is the Goldilocks effect of sports training. Too much activity and you get tired, too little activity and you waste your time, but just the right amount can create PR performances—and keep you from inferno bear consumption. The most common example of this is a heavy squat paired with an explosive jump: done under the right circumstances, this can result in lifetime best verticals.

You might be thinking that PAP sounds overly complicated and not your cup of tea, but I bet you a hot bowl of porridge that you’ve used the concept before and didn’t even realize it. Walk into any weight room, field, or court, and at the beginning of activity, you’ll find almost every single team WARMING UP. Dynamic warm-ups are a great way to improve the function of muscle as well as the subsequent performance—in other words, a very mild form of post-activation potentiation.

Or maybe you’re on the other side of this conversation, saying “Who doesn’t know about PAP?” It’s easy to pair like exercises and think you’ve got a winning formula, but what looks like a good workout complex to a casual bystander might not be the “just right” formula.

Strategies like French contrast training have become very popular, but there is an elephant in the room we need to address. Without tracking intra-workout metrics, you might be introducing more fatigue than potentiation.

Likewise, it seems that stronger and more developed athletes have a greater positive response to PAP than novices.1 So, breaking this out with your U12 soccer team may not be as effective as you thought. Even more, some research has shown that higher performers respond better to the PAP effect of isometric holds as well, while others have no effect at all.2 The novice training effect works in reverse when it comes to PAP strategies—the more trained you are, the better the improvement.

Not Too Hot

I’ve watched numerous videos online where coaches/trainers/influencers prescribe their workout routines trying to use the PAP effect. The flash and pizzazz of the videos look great, but that’s where the success typically ends. By overstimulating to make the workout look hardcore, the results are most likely an over-fatigued and underperforming athlete. This porridge is too hot.

If you don’t track the secondary movement metrics, you might never realize that the training you’re doing is actually not working out so well, says @endunamoo_sc. Share on XIf you don’t track the secondary movement metrics, you might never realize that the training you’re doing is actually not working out so well. The three biggest mistakes I see are always:

- Contrast Exercises without Adequate Recovery Times. This results in too much fatigue. If you’ve ever run a busy weight room, you know what it feels like to have athletes standing around and twiddling their thumbs. And you better gird your loins if the football coach walks in and doesn’t hear screaming and bars banging at all moments of the workout.

- Unfortunately, adequate PAP requires several minutes of passive recovery. It’s okay to stimulate the mind, but it’s very hard not to find something physical to do as well. Although it feels counterintuitive to do nothing, you can supersede baseline performances with longer rest periods. There is hope though. Lower-intensity/lower-duration movements like jumping seem to require less rest than sprinting movements.

- Wrong Stimulus for Desired Output. In most cases, an adequately heavy movement is required before the dynamically fast action. But it’s a fine line between heavy enough and too heavy. You can also utilize more power-based exercises or the right intensity isometric. In addition, most research shows that there is MASSIVE individual variance—meaning, what might work for a more-trained individual will have NO effect on a younger athlete.

- Poor Exercise Pairing. This may not be the end of the world, but it can result in subpar outputs. In theory, any kind of CNS-stimulating act should create systemic improvements—but, in practice, we want to make sure that we line up the square peg with the square hole and don’t just jam a triangle in sideways. In most cases, pairing like movements should yield the best results. The grey space occurs when we have an activity like a sprint, where a bilateral back squat or deadlift can yield huge improvements. It is up to the coach to track the output of the desired exercise and make sure the shapes line up.3

Not Too Cold

I know that most of us aren’t small-engine mechanics, but if you ever struggle to get your lawnmower started, grab a can of carb/choke cleaner and blast it into the choke valve shaft. Once all of the gunk has been cleared, you’ll hear that engine crank. A lot is happening on the inside of that engine, but all you need to know is that this works.

But, as strength coaches, we might need to know exactly what’s happening inside our athletes when we implement certain training strategies. PAP has been attributed to the phosphorylation of myosin regulatory light chains, which makes actin and myosin more sensitive to Ca2+. The potentiated state has also been attributed to an increase in α-motoneuron excitability, as reflected by changes in the H-reflex. In laymen’s terms, the correct exercise can act like a carb fluid that kickstarts performance into overdrive.

To take advantage of this, we can improve the power or velocity of an athlete over time by training at a higher level each workout. For example, if athlete A has a peak vertical at 23 inches and they perform traditional plyometric work, they might perform a series of jumps between 19 and 21 inches. Meanwhile, athlete B has the same vertical but uses a PAP strategy and performs their jumps between 20 and 23 inches. Which one will adapt to greater peak power?

Most likely the one jumping higher: athlete B.

We can improve the power or velocity of an athlete over time by training at a higher level each workout, says @endunamoo_sc. Share on XBy contrast, athlete A missed out on dozens of jumps closer to their peak vertical. We adapt to what we do, and jumping higher requires high jumps. This porridge is too cold.

It’s My Activation, and I Want It Now

I teamed up with my local university in 2019 to produce a study that asked what the ideal percentage of an athlete’s squat 1RM needed to be to acutely improve vertical jump performance. We concluded that 75%–80% 1RM was the greatest and most consistent intensity for our goals. While some research suggests up to nine minutes of passive recovery is effective, we opted for the more realistic one minute of sitting.

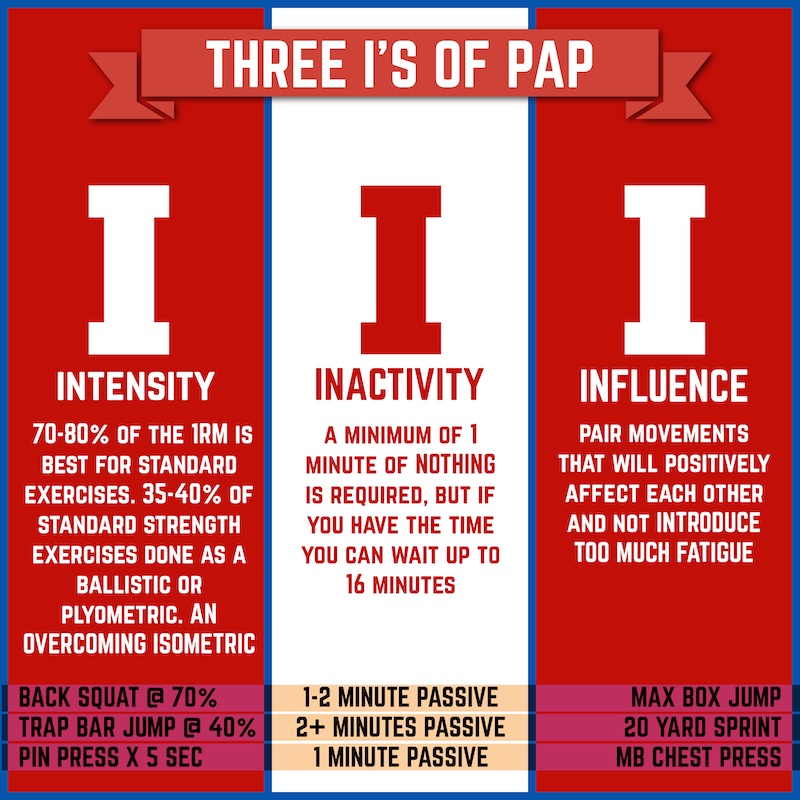

During this data collection, I realized that I had my own faux pas in training. My athletes’ recovery time wound up being closer to 30 seconds—roughly the time it took for them to walk to their next station. And I know that I’m not alone in making this blunder—with so much we want to accomplish, it’s hard to sacrifice time for sitting around. To make sure we find the bed that is just right, I’ve coined the three I’s of PAP:

- INTENSITY—most power-based research suggests that 70%–80% of the 1RM is best for standard strength and power Olympic exercises, or 35%–40% of standard strength exercises done as a ballistic or plyometric.

- INACTIVITY—a minimum of one minute of doing NOTHING is required to stimulate performance, but if you have the time, you can wait up to 16 minutes for more taxing activities like top-speed sprinting.4 (You will have to decide based on your resources and the secondary movement’s output.)

- INFLUENCE—we should be pairing movements that will positively affect each other and not just take up time. If your goal is to improve max vertical jump, pairing bench press with box jumps might not be the right call.

The Newest Trick in the Book

In August 2018, during the NFL’s Brown’s football warm-ups, the world was humored by Assistant O-Line Coach Bob Wylie when he said, “Did you know, World War I and World War II, all those guys that fought in that war…they did…none of this fancy [expletive]. And they won two World Wars. Do you think they were worried when they were running across Normandy about [expletive] stretching?” Coach Wylie’s opinion on properly warming up before activity is one that died with the old guard years ago. The world of sports has evolved past this instance of ignorance, but we still have some muddy waters to traverse.

The new “dark age” we need to get out of is ignoring the benefits of a good pre-game lift. I asked a few coaches why they wouldn’t do pre-game lifts or even day-before workouts, and the most common answer was “We don’t want to be sore.”

This would make sense if you don’t weight train during your season, but I’m going to assume this isn’t the case for most of us. Long-term PAP is often referred to as post-activation performance enhancement (PAPE) to distinguish between short-term training gains and long-term sports improvements.

When done correctly, resistance training can be a primer to enhance performance on game day. Training as close as six hours before a game can have significant improvements on your team’s performance.5 But if that makes your football coach uncomfortable, that’s okay; you can even train the day before and still see some enhancement in things like power and sprint times.6 The catch is that most of the training should be lower volume, moderate intensity, and power based.

Don’t Overcomplicate Things

In college, we all go through a program or take a test called “Practicum.” It’s like taking a nurse out of the classroom and putting them into a hospital setting to see what they’ve learned (also known as clinicals). Below is a quick example of how to take PAP and PAPE from strategy to application.

There are many ways to use PAP in your training; I just recommend you use SOME form of metric monitoring. It’s tempting, but don’t fall victim to overcomplicating a simple thing, says @endunamoo_sc. Share on XThere are many ways to utilize PAP in your training, but my only recommendation is that you have SOME form of metric monitoring. It is tempting, but don’t fall victim to overcomplicating a simple thing. There are other systems to utilize PAP or PAPE, some of which are called contrast training. (French contrast training is a popular model.) For most of our athletes, LESS is MORE, and adding layers could negate some of the benefits.

To determine whether you chose the right system or adhered to the three I’s of PAP, you simply need to track how the secondary movement is affected. If you see a drastic decrease in the desired output, you might need to adjust the rest length, the exercise volume/intensity, or both!

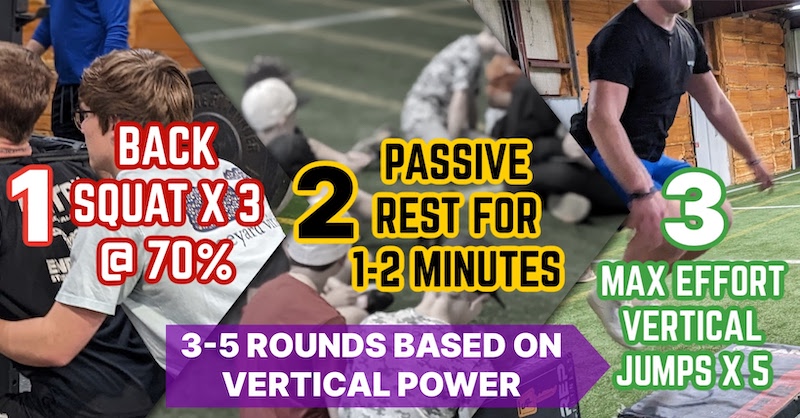

PAP

Squat x 3 @ 70%

Rest x 1 minute FULL

Max Effort Jump x 5 (An easy way to track this is with a box jump set at a specific height -or- an object touch like a rim -or- jump mats)

*Complete 3 to 5 rounds

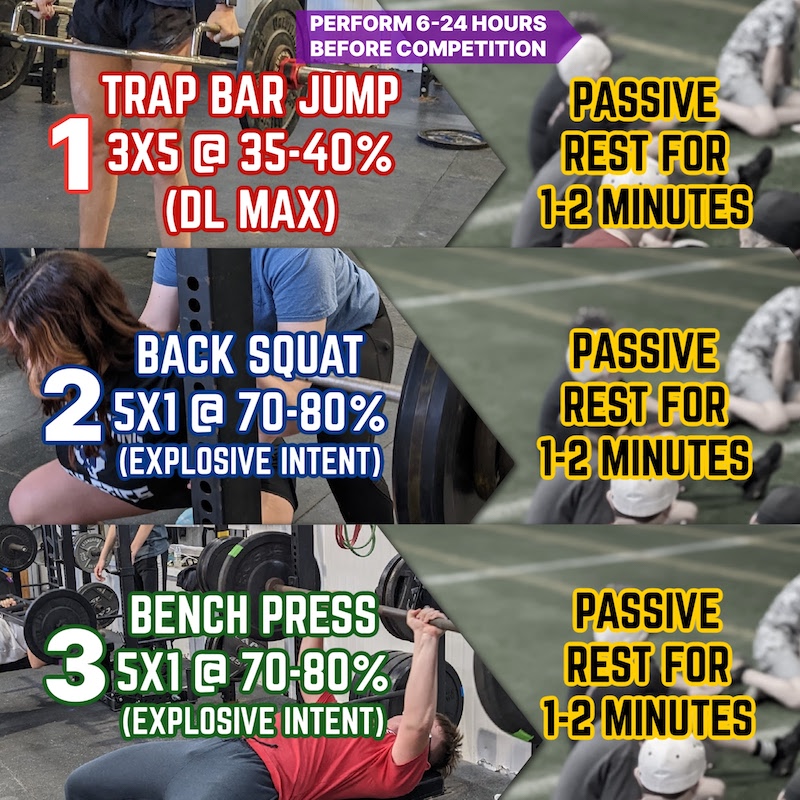

PAPE

Trap Bar Jump 3×5 @ 40% (DL MAX) Rest x 1–2 full minutes between bouts

Back Squat 5×1 @ 70% (explosive intent) Rest x 1–2 minute between bouts

Bench Press 5×1 @ 70% (explosive intent) Rest x 1–2 minute between bouts

This One Is Just Right

Utilizing PAP or PAPE cannot be your entire training philosophy, but you shouldn’t ignore the nice employee trying to hand you the deal of the year because a checkout line is right there. We didn’t even talk about long-term progression or how to include conditioning or other qualities a good S&C program would need. But PAP is a tool that can help most programs get more out of their training.

PAP is a tool that can help most programs get more out of their training, says @endunamoo_sc. Share on XA quick Instagram search turned up ZERO accounts that have post-activation potentiation in their username. (I have found this the best way to determine whether something is trendy and has a shelf life.) That being said, if we can implement PAP principles within our training, we might find the perfect porridge to get the results our athletes are growling for. Goldilocks might not have had the ending she wanted, but we S&C coaches have a real shot at making our bears, er, head coaches, say “JUST RIGHT.”

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

1. Seitz LB, de Villarreal ES, and Haff GG. “The Temporal Profile of Postactivation Potentiation Is Related to Strength Level.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 2014;28(3):706–715.

2. Tsoukos A, Bogdanis GC, Terzis G, and Veligekas P. “Acute Improvement of Vertical Jump Performance After Isometric Squats Depends on Knee Angle and Vertical Jumping Ability.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 2016;30(8):2250–2257. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000001328. PMID: 26808841

3. Chmiel J, Carillo J, Cerone D, Phillips J, Swensen T, and Kaye M. “Post Activation Potentiation of Back Squat and Trap Bar Deadlift on Acute Sprint Performance.” International Journal of Exercise Science: Conference Proceedings. 2016;9(4).

4. Bevan HR, Cunningham DJ, Tooley EP, Owen NJ, Cook CJ, and Kilduff LP. “Influence of Postactivation Potentiation on Sprinting Performance in Professional Rugby Players.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 2010;24(3):701–705. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181c7b68a

5. Mason B, McKune A, Pumpa K, and Ball N. “The Use of Acute Exercise Interventions as Game Day Priming Strategies to Improve Physical Performance and Athlete Readiness in Team-Sport Athletes: A Systematic Review.” Sports Medicine. 2020;50(11):1943–1962. doi: 10.1007/s40279-020-01329-1. PMID: 32779102

6. Tsoukos A, Veligekas P, Brown LE, Terzis G, and Bogdanis GC. “Delayed Effects of a Low-Volume, Power-Type Resistance Exercise Session on Explosive Performance.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 2018;32(3):643–650. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000001812. PMID: 28291764