[mashshare]

When tasked with delivering a plyometric plan for athletes, it can be easy for us to slip into a progressive way of programming. The desire today for bigger, better, and more extreme movements in dynamic training is leading us down the route toward a constant need for some sort of statistical progression. Whether that’s the height of a box, hurdle, or jump, we now yearn to continually raise the bar in jumps training (pun 100% intended).

Movements that lack an instant measure of progression often get pushed aside in favor of exercises that are pleasing to the eye and more likely to get engagement on Instagram. Coaches who understand the intricacies of performance in sport know that progression and the constant need for it can have a detrimental effect on athletes.

Movements that lack an instant measure of progression often get pushed aside in favor of exercises that are pleasing to the eye and more likely to get engagement on Instagram. Share on XWhether your athletes compete in track and field or team sports, you know that a developmental program that spans the playing/competing year can set up an athlete for success. If we enter the year with certain movements and continually progress them until the competitive season, the likelihood is that injury risks will increase, and adaptations will hit a plateau. So why do we repeatedly see plyometrics on this progressive continuum of athletes trying to leap 3 1/2-foot hurdles? In my opinion, this is all due to a misinterpretation of Verkhoshansky and Siff’s Supertraining and a lack of education around locomotive plyometrics.

The Truth About Plyometrics

The name “plyometrics” has always had a slight folklore to it, with rumors about a background in Russian-style shock methods with 3-meter depth jumps and hundreds of meters of hopping and bounding. But from day 1, Verkhoshansky’s “Fundamental Theory of Plyometrics” followed five simple phases that determined an athlete has to land to then take off for the movement to be considered plyometric.

- Initial Momentum Phase: The body moves due to the kinetic energy produced from a preceding action.

- Electromechanical Delay Phase: Coined to mean the start of the electrical signal to the start of the mechanical contraction in a muscle. Some may define this phase to include the lengthening of the series elastic component (SEC) of the muscle complex.

- Amortization Phase: When kinetic energy produces a powerful myotatic stretch reflex. This phase bridges the eccentric and concentric phases of a landing and takeoff.

- Rebound Phase: This phase marks the release of elastic energy from the SEC, together with the involuntary concentric muscle contraction.

- Final Momentum Phase: When the concentric contraction is complete, and the body continues to move by means of kinetic energy from the Rebound Phase. This phase will then restart the cycle in preparation for the next movement.

Despite this, there is a lingering fear and assumption that we require a stimulus (i.e., a hurdle) or a selected height to fall from (i.e., a box) to stimulate tissue for an adaptation. Or an altogether incorrect format of jumping—learning how to lift your knees—with static box jumping.

As a high jumper, I spent at least 3–4 years doing plyometrics and never needed a hurdle or platform to create the violent eccentric lengthening that comes with this form of training. Yet, at a similar time during my undergrad, lecturers and coaches were telling me that youngsters weren’t allowed to do any plyos until they reached a certain age due to high injury risks and dangers. Since then, I have always countered this with what I term “locomotive plyometrics” (meaning, any form of dynamic movement that cycles through a landing to takeoff action in under 0.25 seconds).

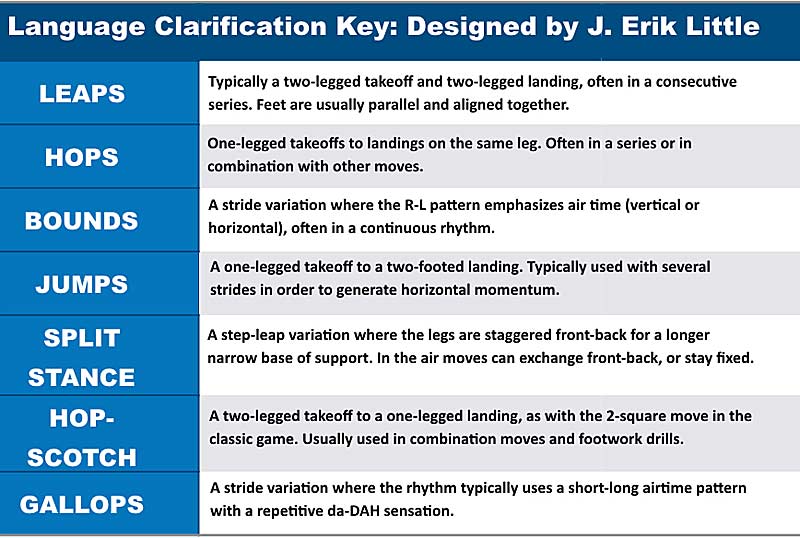

Locomotive plyometrics allow for an infinite number of movements that create adaptations for the KPIs needed in dynamic sport, says @mcinneswatson. Share on XI took the term “locomotive plyometrics” from my old coach and mentor, Erik Little, who devised this developmental system for plyometrics over the past 40 years. The system allows for an infinite number of movements that create adaptations for the KPIs needed in dynamic sport, including movements that teach athletes how to deal with overload, velocity, stability, and even mobility. Little designed original categories for plyometrics, and I have developed upon them. These tiers of locomotive plyometrics, along with categories of slower jumping methods, support the adaptational growth between the murky grounds of weightlifting and high-speed training.

Looking back at equipment, I’d be wrong to totally condemn the use of hurdles and boxes for plyometrics. There is a time and place for these types of movements, and it’s at the more elite level. (Although, do not assume that any elite sportsperson can depth jump or leap hurdles, because there is a very small minority that can execute these well.) Our typical human inclination to copy the elite often leaves athletes making many mistakes.

Some common problems are:

- When trying to leap hurdles, priority #1 is usually to clear the obstacle. In my opinion, landing mechanics should always be your #1 concern, and if you wish to elicit a certain type of landing, then cue it.

- If you’re going to use hurdles, mini hurdles, or boxes, then create a system that spaces them accurately. Again, this is a huge issue with destroying any specific cue you may want as a coach. Using numerical sequences like the Fibonacci sequence can help to space things with a natural growth of distance. (Note: Use your feet to pigeon-step out obstacles.) Nine times out of 10, obstacles are spaced in such a way that they destroy landing mechanics.

Remedies for issues:

- Removing obstacles allows much more freedom for movement. This form of training is to teach athletes to move with grace, and gracefulness doesn’t flow in a constraint-based environment.

- Doing simple things, like asking your athletes to lift their knees as if to leap through hurdles, takes away the dangers of using obstacles, but at the same time can create the potential dynamic landings you may get from hurdle leaps.

- Finally, the beauty of locomotion-based plyometrics is that they allow athletes to self-select their falling heights—i.e., if I am to leap roughly 30 centimeters into the air, my next landing will have roughly the eccentric landing forces of a 30-centimeter depth jump. This takes away the fear of the unknown and uses a much more natural muscular sequence.

Developmental Tiers of Plyometrics

As mentioned before, the idea that plyos have to be shock-based is a myth. The use of submaximal and lighter versions allows for a greater scope of variation to help with accommodating the diverse needs of multiple sports.

The idea that plyometrics have to be shock-based is a myth. Submaximal and lighter versions allow for greater variation to help with the diverse needs of multiple sports, says @mcinneswatson. Share on XCategorizing plyos over my years as both an athlete and a coach has allowed me to organize movements into more of a hierarchy for developmental learning. Much like Bondarchuk’s periodization principles, there are foundational general prep movements that realistically never leave your program. The competitive year is then focused on becoming more specific toward the sport—in this case, the specificity from the plyos is the velocity and force of the movements.

Reasoning Behind the Tiers

Note: Using locomotive plyometrics and leg dynamics as part of your programming is a great way to teach athletes how to move, deal with overload, stabilize, and continue the direction of kinetic energy and velocity with grace.

Each tier can range from 1–10 movements (it could even be 50 if you had the reasoning), depending on the level, experience, and phase of the year. These can be a mixture of any of the plyometric movements listed in the key. Think about varying a hop (unilateral—one-legged to the same leg) followed by a leap (two-legged to two-legged) to perhaps give the legs a slight rest and bring variation to the tier. You can determine all variables based on the athlete’s needs, but I note suggested distances to cover below.

Disclaimer: The distances suggested are just recommendations, and coaches are responsible for athlete prescription. You should monitor the volume and intensity of movements for each athlete. As soon as landings become heavy and flat, it’s a case of diminishing returns, and injury risks will start to increase exponentially.

Footwork/Light Tier: 5–15m distance, due to the high number of small landings.

The lighter tiers (or, as I call them, “footwork” movements) are a great starter and introduction to load. They aim to keep GCT short and joints relatively stiff, and the eccentric loading remains low due to them not being maximal. The idea is to create a nice compliant bounce to the movements to enable strong neuromuscular learning to take place. You can prescribe this tier in high volumes, due to its reduced loading. You can also use it as a tool to increase joint stiffness of the lower extremities when the volume of landings is high.

Video 1. Leg Exchanges Plyo. This light tier of “footwork” plyometrics is perfect as a starter to activate for further dynamic work and a great reintroduction to landings when returning from injury. They’re also valuable for learning neural patterns of movements—try these barefoot on grass or on mats to get a good feel.

Keys: Short GCT, low GRF, neuromuscular control, rhythmical landing-takeoff patterns. Stiff joint, little compression, light sensational landing.

Medium Tier: 10–40m, greater distances for bigger movements like hopping and bounding

If anything, our medium tier is the bread and butter of locomotive plyometrics. Although not necessarily maximal, medium tier plyos are still violent due to the velocity of active limb striking. Eccentric GRFs are within the range of hitting over 4–5x BW, while GCT remains very fast.

With the locomotive properties of medium tier plyos, there should be a natural flow and relaxed state to airborne movement, covering ground gracefully. High loading and fast GCT mean that volumes can’t be too high, but they have a place year-round in a program and should be a staple part of keeping general prep fitness up. This tier is a good teacher of typically cyclical movements, with loading and unloading patterns that utilize the SSC.

Video 2. Med Bounds Plyo. Depending on the phase, athletes can perform the medium tier plyometrics on hard tracks/courts or soft grass and mats. If the movement doesn’t flow well, take a step back and slow down the traveling velocity of the movement.

Keys: High speed = short GCT, submaximal GRF, cyclical rhythm. Athletes should seek to cover ground efficiently.

Dynamic/Ping: 5–20m, shorter distances due to fewer landings

The phrase “Ping” is part of the cued terminology used for locomotive plyometrics. It asks for exactly that—a movement where you ping off the floor, being highly reactive and dynamic. You could relate Ping movements with depth jump landings. They are maximal, shock-based, fast GCT, high GRF, and as stiff as possible.

Due to high intensity levels, the volume of Ping work can’t be too high, but a small number of landings can produce good adaptations. When cued for, coaches can ask for maximal heights, distances, and speeds. (Note: This should only be done if the athlete’s landings remain within the Ping parameters. If the GCT is too long or the joint stiffness is decreasing, then regress as necessary.)

Video 3. Ping Leaps Plyo. Use only hard surfaces for this type of work to keep GCT down. Even if jump height and/or distance aren’t great, make sure the emphasis is on being as dynamic as possible (minimal joint distortion—reactive pop to the action).

Keys: High speed = short GCT, high GRF, as reactive and dynamic as possible.

Supporting Methods

Deep: 5–20m, often shorter distances, due to slower-moving velocities.

The Deep tier is exactly as it sounds—movements are much deeper in ROM and joints absorb and flex much more. This is not to say that eccentric GRF can’t be high, but GCTs are likely to be outside of what’s seen as the plyometric realms of less than 0.25 seconds. With this, the coupling of the eccentric and concentric phases is somewhat less effective, and there is an obvious isometric period to deep movements. The series elastic component is not utilized, as is seen in true plyometrics, so the movements become more muscular-focused and the concentric phase is a more obvious push. High levels of stability, through greater ROM, are needed to control posture and alignment when absorbing force in deep movements.

Video 4. Deep Leg Exchange Plyo. This tier is a great tool for recognizing imbalance and a lack of range at a joint. Having an athlete do deep leaps will straightaway test the positive shin angle and mobility around the ankle. This sort of information can collectively help remedy issues that may arise at much faster speeds.

Keys: More shock-absorbing = longer GCT, high stability, greater mobility = deeper ROM, greater postural control.

Locomotive plyometrics can help build a more dynamic and athletic individual and enable coaches to develop a more holistic program, says @mcinneswatson. Share on XDevelop a More Complete Athlete, and Program

This system of tiers for plyometrics has enabled me, as a coach, to employ these types of dynamic movements for all levels and types of athletes. The use of a developmental system provides a platform for athletes to grow year on year and avoid plateaus at certain stages. The capacity for locomotive plyometrics to build an overall more dynamic and athletic individual enables you to develop a more holistic program that hits critical KPIs for dynamic sports.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

[mashshare]