A few years back, I began working with an athlete who was coming off a very serious and rare form of thoracic cancer. For the sake of this article, we’ll call him Jake. He underwent multiple major surgeries over several years that required doctors to cut through his pec muscles, serratus anterior, lat, and about 40% of his upper abdomen; all of these surgeries were on the right side of his body. Due to the location of his tumors, they also had to break his sternum and several ribs to get to what they needed. His body was ravaged—a truly harrowing experience, to say the least.

Despite the hardships, Jake was fully committed to seeing his career through and was working his way back to being operationally fit for duty. I was extremely fortunate to be a small part of his return.

Debates on whether unilateral imbalances are detrimental, beneficial, or completely insignificant to sport have been fevered for years. And, in most cases, they have often been very siloed and shortsighted. The experience of working with profound cases, such as Jake’s, has helped me develop a broader perspective on the entirety of asymmetries. As such, in this article, I’d like to focus the discussion on the spectrum of asymmetrical imbalance and how it affects athletes/individuals spanning a variety of sport backgrounds.

[adsanity align=’aligncenter’ id=11130]

Assessing Asymmetries

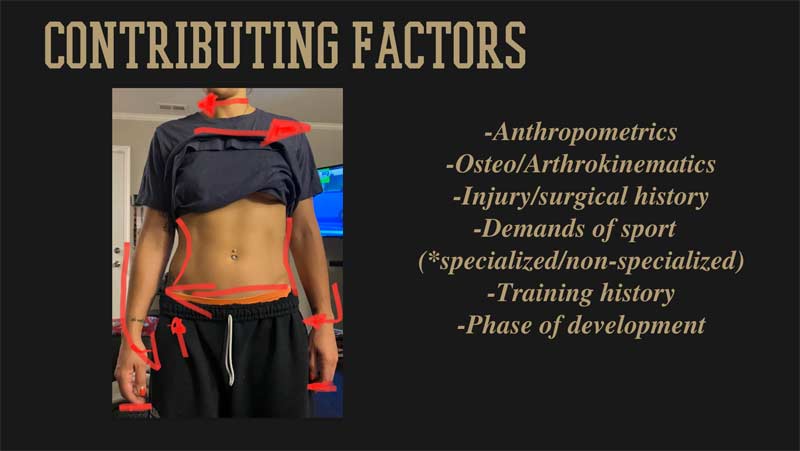

Rather than simply seeing asymmetries in sport as either good or bad, we need to appreciate the complexity and nuance. But the first priority is understanding that there are several variables to consider and numerous ways to discern the significance of unilateral imbalances. These factors are more or less significant depending on the athlete’s stage of development, the demands of their sport, and the position they play. A short list of the more prominent factors can be found in the graphic below.

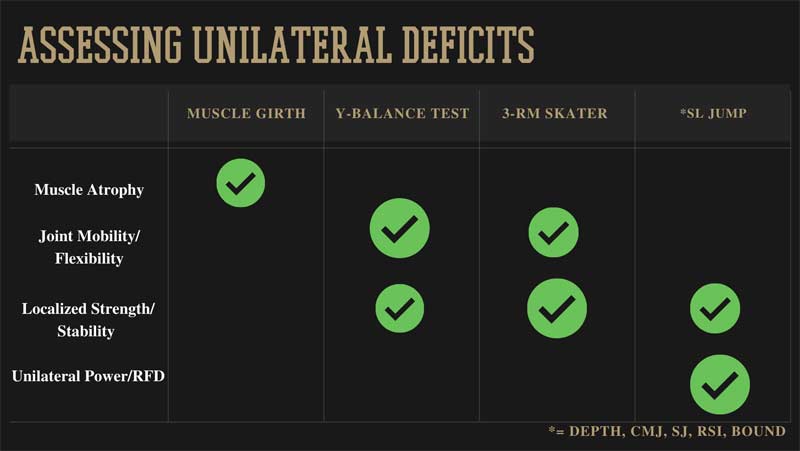

Additionally, there are numerous ways to assess unilateral imbalances; again, with the testing priority and significance being determined on an individual basis. A few of my unilateral baseline assessments typically include left/right muscle girth (muscle atrophy), functional unilateral movements such as a loaded skater squat (strength), and a Y-balance test (stability/mobility). These are reasonably simple tests with high degrees of reliability that allow you to observe the margin of difference between sides with your athletes.

Few coaches would argue that comprehensive unilateral testing is a logical part of an athlete’s training process; however, the heated question remains whether these margins of difference should or shouldn’t be addressed or “corrected” with our athletes. The unfortunate reality is this just isn’t a cut-and-dried situation, and rather than seeking empirical boundaries or ranges, unilateral deficits should be viewed individually and as a spectrum—or, as I see it, functional or nonfunctional.

Few coaches would argue that comprehensive unilateral testing is a logical part of an athlete’s training process, but they disagree on whether the margins of difference should be ‘corrected.’ Share on XFunctional vs. Nonfunctional Asymmetries

A subtlety to the military population is recognizing that a large portion of their work demands are unilaterally dominant (e.g., shooting stance, swimming stroke, vehicle position, kit/weapon positioning). Given the extreme volumes and intensities they are exposed to, not only do unilateral imbalances result, but damage and injury are all but inevitable. Thus, almost every athlete I work with has nonfunctional asymmetries, and a robust injury history.

By determining whether an athlete’s asymmetries are functional or nonfunctional, we can create a clear delineation that can help guide training priorities and programming selections. This does not indict the athlete in any way; as I see it, this is just an arbitrary way for coaches to have a better foundation for training prioritization and specificity. Functional imbalances do not need to be deliberately addressed, as they likely offer more benefit to sport performance than they do potential injury risk.

Nonfunctional imbalances, on the other hand, should be a top training priority, as egregious margins of difference between sides can become an impediment to performance and an injury vulnerability. The predominant factors outlined above, in conjunction with the amount of asymmetrical imbalance, will determine how much we should emphasize reducing the margins of difference in training.

We need to recognize that all asymmetries are not created equal. Speaking specifically for athletes—especially at higher levels—they need unilateral dominance. I see this as “protective tension,” whereby the demands of competition over the course of several years have driven unique, specialized differences in morphology or function that are optimal for their performance. Sticking with the baseball example, consider the throwing shoulder and contralateral hip of a pitcher. The throwing arm will have unique adaptations—hyperlaxity (elbow), increased rotator cuff thickness, lat extensibility, etc.—that are needed for them to perform at a high level.

We need to recognize that all asymmetries are not created equal. Speaking specifically for athletes—especially at higher levels—they need unilateral dominance, says @danmode_vhp. Share on XI believe there are two priorities here:

- Don’t disrupt the imbalances too much while in-season; let the player help determine what the best ratio of differences may be.

- During the off-season, address these margins of difference to recalibrate equilibrium and avoid egregious discrepancies.

The goal will be to work the athletes back away from the outer (extreme) ranges, so they go into the following season with more room for regression throughout the year. Analyzing it this way, you see why simply saying “asymmetries don’t matter” or “asymmetries always matter” is shortsighted and incomplete.

Video 1. Dumbbell offset single leg RDL. Off-season training may be the best time to program exercises to address asymmetries.

Determining Significance

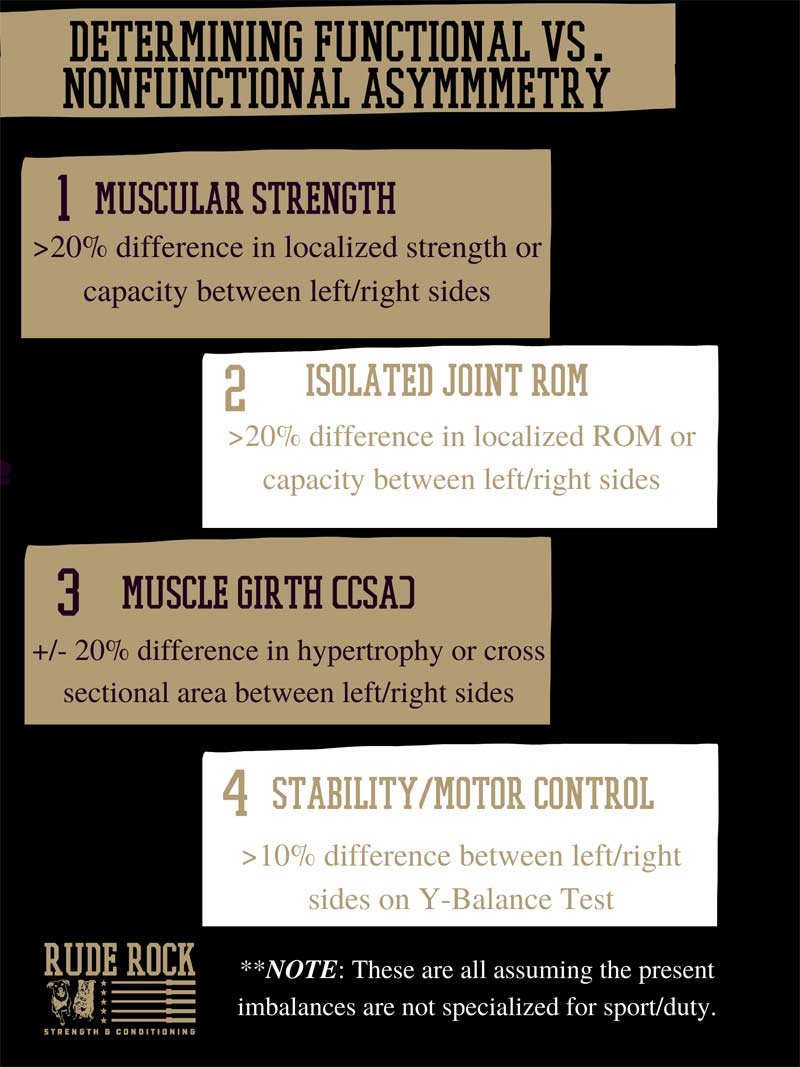

It all comes down to what coaches/practitioners deem to be a significant difference, given the constructs of their sport. Considering my tactical population doesn’t need much unilateral dominance for the sake of performance, I try to simplify this by observing four primary criteria:

- Muscular strength.

- Joint ROM.

- Muscular girth.

- Stability/motor control.

Within each of these, I’ve observed that ~20% unilateral difference is loosely indicative of impaired biomechanical function and injury vulnerability for what their job demands of them.

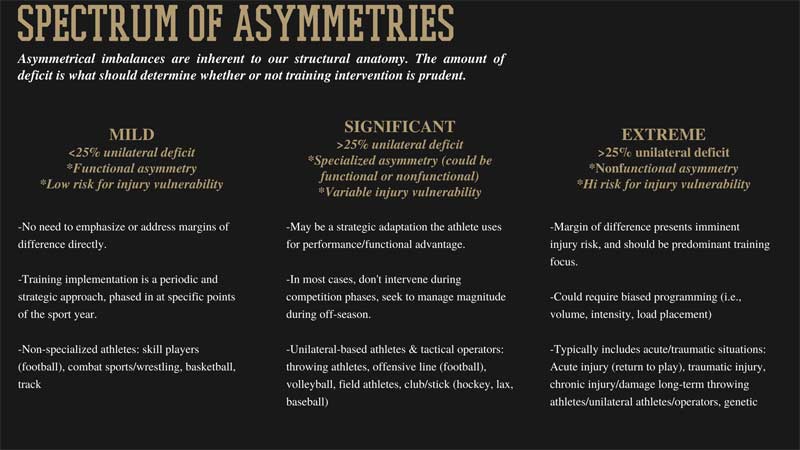

We can then identify asymmetries as mild, significant, or extreme.

- Mild asymmetries are functional imbalances that present no increased likelihood for performance decrement or injury risk. This speaks to most non-specialized athletes and most individuals; in this case, unilateral deficits do not need to be a training priority.

- Significant imbalances are those that meet the criteria outlined above but may or may not provide functional advantage. This speaks to specialized athletes (i.e., throwing/OH athletes, stick sports, and field event athletes). You will need to strategically place the management of the margin of deficit throughout your training calendar.

- Extreme deficits occur mostly through injury (return to play), chronic development, or traumatic situations such as Jake’s. With these athletes, closing the gap is the main priority.

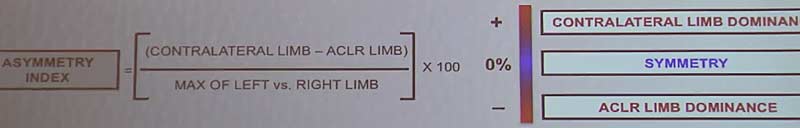

One area of the unilateral debate that appears to be less contentious is return to play. Dr. Matt Jordan, a world-class coach renowned for his extensive research on the neuromuscular aspects of return to play, is someone I’ve learned a lot from on this subject. In one of his studies on ACL return to play, the research team suggested that greater than 20% differences in L/R force profiles following ACL reconstruction place the athlete at a greater risk for reinjury. This was determined using the equation provided below. It was also importantly noted that strength deficits in this instance aren’t only injured versus uninjured side, but also the injured leg post-injury compared to pre-injury.

In the case of return to play, I would advise strength coaches to be vigilant in testing/assessing unilateral deficits once they’ve finished formal physical therapy. Bear in mind that in most PT/rehab settings, the protocols are often localized and isolated in nature. Where the PT’s job is to restore independent function and localized strength, I see our side of the return to play spectrum as restoring strength in a global and integrated sort of way.

Strength coaches should be vigilant in testing/assessing unilateral deficits once an athlete finishes formal PT. Our side of return to play is restoring strength in a global and integrated way. Share on XUsing the post ACL rehab example here, the PT will improve things like knee flexion/extension ROM and strength, while we improve load tolerance on split squats and the ability to cut/change direction between the injured and uninjured leg.

Addressing Deficits

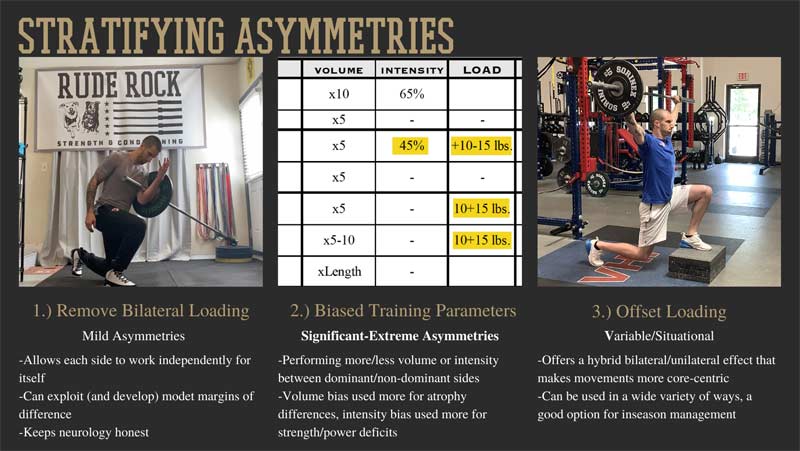

There are three specific ways I go about addressing unilateral deficits, which for the most part can correspond to the degree of significance as outlined above. These strategies are removing bilateral loading (mild asymmetries), using biased training parameters (significant/extreme), and offset loading, which can be used in a variety of ways across the spectrums of asymmetry.

1. Removing Bilateral Loading

Removing bilateral movements from programming effectively forces each side to work independently for itself. This can be a good way to exploit less obvious unilateral deficits and challenge the athlete to work on less familiar patterns. When used strategically, this can be a simple and effective strategy to keep the body honest unilaterally. One population that I feel this is particularly applicable with is Olympic weightlifters. Although the sport of Oly is largely bilateral in nature, there is a high volume of unilateral dominance that accumulates over time due to the mechanics of the split jerk.

Considering the jerk is always performed with the same leg coming forward, this can take a toll on the hips and low backs of Oly athletes. Another subtlety to consider with the split jerk is the disproportionate stress placed on the feet and ankles during the jerk actions. A disruption to the ankle/foot (e.g., chronic turf toe in the back leg, immobilizing the talus on front leg) can have a global impact and become a significant impediment to training.

2. Biasing Program Parameters

This is something reserved exclusively for athletes who’ve exhibited significant, nonfunctional asymmetries. The use of programming bias is a nuanced approach and something that can be undertaken in a variety of ways. But to keep this simple, the purpose of using biased programming is to stress the non-dominant side “X%” more in training.

Broadly speaking, I use increased volume (i.e., more sets—not reps—on the nondominant side) to address muscular atrophy in early phase programming. Then, in later phase programming, I use increased intensity (i.e., relative higher loads on nondominant side) to close the gap on strength/power deficits.

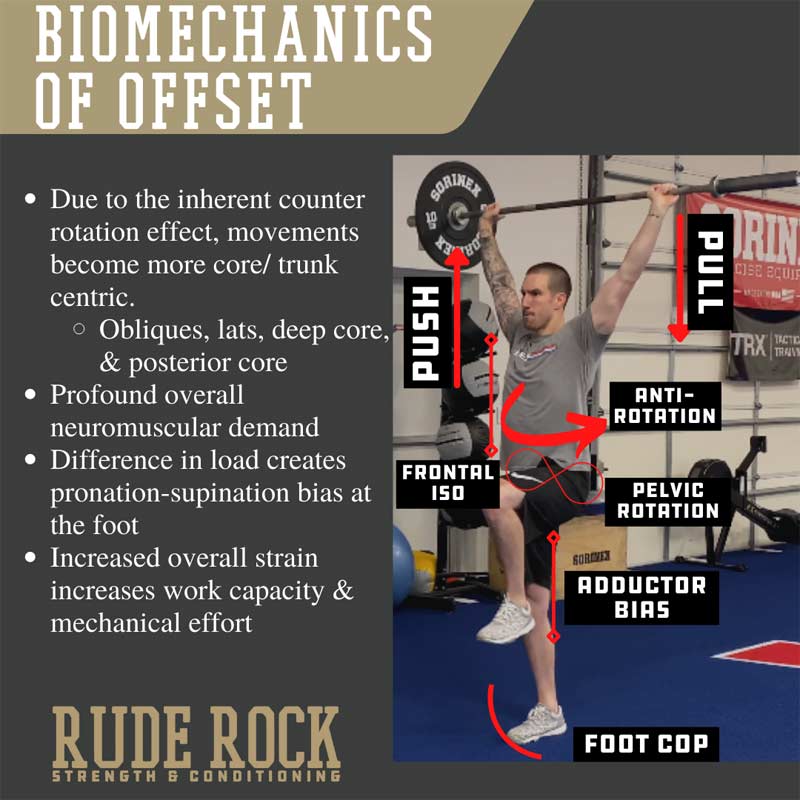

3. Offset Loading

Offset is a versatile training application with an array of benefits. I recently published an article describing the benefits of offset loading for a sport performance population, but, as it applies in this context, offset work can be beneficial for addressing unilateral imbalances. In a sense, offset loading provides a unique effect in that it emphasizes one side of the body but still demands output from both. Movements become more demanding on trunk stability and core musculature and, I’d argue, collectively demand more from muscle groups (increased motor unit recruitment).

In a sense, offset loading provides a unique effect in that it emphasizes one side of the body but still demands output from both, says @danmode_vhp. Share on X

When we have a substantial margin of difference between the left and right extremities, there are numerous trunk adaptations that must subsequently take place to accommodate this unilateral dominance. And a residual effect of this can become the amount of torsion experienced at the spine, as the athlete has recurring disproportionate stress at certain junctions or on the discs themselves. While this may be difficult to measure in the practical sense, it’s important to appreciate that margins of difference between deep core muscles and offset loading offer a very simple way to attack the deficits effectively.

Programming Considerations

Programming variables are collectively based on how significant the deficits are and in accordance with the demands of sport/specialized development. Functional asymmetries do not need to be stressed as a priority; however, I believe there is merit to utilizing some of these strategies irrespective of imbalances. When specifically addressing nonfunctional imbalances, however, we should address the margins of difference by modifying programming variables and exercise selection.

In the case of Jake, over time the nature of his injuries shifted the way he did everything—from his posture to his gait and everything in between, he now accommodated for his right-side deficits. During our initial assessment, Jake had a more than 20-degree difference between left and right hip extension (deficit on left leg), significant differences in hamstring strength (deficit on left leg), and ankle dorsiflexion (deficit on right ankle). So, in addition to the more obvious unilateral imbalances on the right side of his upper body, we were really attacking this from all angles.

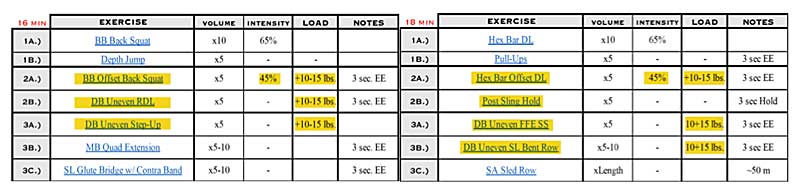

When specifically addressing nonfunctional imbalances, we should address the margins of difference by modifying programming variables and exercise selection, says @danmode_vhp. Share on XI’ve used biased programming in a handful of cases, and this was certainly a feature of Jake’s programming. We followed a protocol of progressively increasing volume discrepancy (2:1, 3:1, and 4:1) with concurrent decreases in load discrepancy across a six-week training split. The volume bias proved to be effective, as we reduced the difference in arm circumference from around 4 inches to around 2 inches between the right and left biceps. We also worked in a good bit of offset loading, which I felt was specifically beneficial for his general motor control and trunk stability. A full breakdown of our programming split can be found in the graphic below.

Video 2. Dumbbell offset incline press.

On a micro view, the main goal with our primary lifts was to find exercises we could apply heavy loads to and create a high CNS strain. For Jake, these mainly included hex bar deadlifts and push press variations. I like to “double down” on primary lifts, loading both conventionally and in an offset fashion (see 1A/2A below). The secondary focus was to challenge motor control and trunk stability. We accomplished this utilizing a number of offset variations—DB/KB uneven applications for presses, pulling, and hinge patterns as well as a lot of band offset movements: split squat, marching, and bridge variations. A full sample is shown below:

Jake was one of those athletes who will forever stick with me. Not just because our time together became a catalyst for how I perceive training methods, but more so due to the indelible impression his valor and determination made on me. In a relatively short time frame (six weeks), Jake saw tremendous progress, adding 11 pounds of muscle, dropping about 2% body fat, and showing significant improvements in strength and capacity. Although we didn’t completely resolve Jake’s unilateral deficits, arbitrarily I would say he went from ~50% margins to ~25% across the board. This enabled him to continue his career, have control over his future, and, most importantly, continue to be a husband and father…which is what matters most.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF