In the last several years, there has been an apparent divide on social media about the best ways to train to obtain certain results. What has also become apparent is that, while both participants in the argument have typically had great results, they each advocate for polar extremes of training. Sprinting, for example, has a growing divide over whether to program excessive amounts of submaximal, high-volume tempo work or maximal intensity, low-volume sprint work. As discussed in my previous article, each approach has its pros and cons, but why does training have to be polarized? What makes one training approach right and another training approach wrong? One word: context.

When we talk about context in these conversations, we are often ignored by both training groups and swept under a rug in the discussion. If I approach the monotonous tempo crew and ask “Hey, what about max speed?”, I may get a sarcastic retort consisting of “What about it?” or they may disregard my argument by saying “We get our speed work in at meets!” If I approach the max speed crew and ask “What about endurance?”, I again get a sarcastic response of “What about it?” or my argument is met with the same solution: “We race into shape in meets!”

The irony of all of this is that they each answer my questions similarly, yet totally resent one another’s approach to training and refuse to entertain a happy medium. This middle ground approach, where I tend to be, allows me to use a more holistic training model that revolves around the context of the sport and each individual athlete. I tend to take valuable pieces from both camps of thought in order to design a more well-rounded program, addressing all aspects of speed development rather than one extreme or the other. It doesn’t have to be an either-or approach, and I think that is important to note.

While there is no single approach that will universally apply to everybody I train, I do have several foundational principles that I use when designing a training program. These pillars of my program help guide which approach I use while also encouraging constant reflection in order to refine decision-making to best serve the athlete. There is not an exhaustive list of principles in my training model, and it isn’t meant to devalue core concepts in anyone else’s program, but it contains just a few things that I’ve found particularly valuable over time. Here are six principles that are central to the way that I approach training.

1. Athletes First

A program centered around the athlete allows for you to home in on the most important qualities in the training equation. This is very multifaceted and can be as simple or complex as you make it. Ideally, you use the context around the athlete to direct your initial programming thoughts and build from there. This list contains (but is not limited to): training age, injury history, sport, position, practice schedule, prior training successes and failures, structural variance, current level of performance, and much more.

Contextual programming means that you address the things that matter most to the athlete and their performance in their respective sport(s). With this approach, you may choose to address similar qualities in different athletes with different workouts. Conditioning a soccer player should look much different than conditioning a football player. While speed training for track athletes may look similar to speed training for ball sports, there are components specific to track and field that may not be very useful for ball sport athletes.

Additionally, an athlete who has poor speed might be trained differently than an athlete with great speed. Younger and older athletes may not respond the same to similar training stimuli. While one might bounce back great, another might take a week to recover or even get injured. All of this is to say that a one-size-fits-all approach to training has not generally worked for me personally nor for my athletes. Taking the time to process information, backgrounds, and goals for each athlete I work with has helped guide my training and make it more meaningful overall.

Being mindful of the context behind what the athlete needs from me versus what I need from the athlete has made a large difference in individual responses to training stimuli, says @BrendanThompsn. Share on XAn athlete with an injury history, especially a lingering injury, should have a unique approach to training compared to an athlete with a clean bill of health. This is not to say that we need to necessarily baby the athlete, but there need to be attempts to strengthen any glaring insufficiencies in training prior to layering on a large workload. These training qualities include movement, strength, stability, endurance, balance, coordination, and much more. Being mindful of the context behind what the athlete needs from me versus what I need from the athlete has made a large difference in individual responses to training stimuli.

This same principle has held true for me in the physical therapy world. Many practitioners (me included) have fallen into a routine where they see a patient with a given ailment and give them similar treatments regardless of their current level of functioning and goals. When shifting the view to see the patient as a whole and providing holistic care, many notice patients are willing to do more, including doing their exercises at home and performing functional tasks as instructed more consistently. In my experience, it also seems to yield much better results both subjectively and objectively. Making the program make sense to the athlete sets you up for more trust in training and subsequent follow-through overall.

2. A Foundation of Movement

To me, sport and overall human performance are based around principles of various movement qualities to achieve success. Centering the way I train around this very basic idea has enabled me and many of my athletes to improve overall efficiency and decrease risk of injury.

One tendency I’ve seen frequently is for football players, and high schoolers in general, to be extremely devoted to the weight room. They train themselves to produce massive amounts of force, yet their performances tell me there is a disconnect somewhere. Focusing on movement economy allows these athletes with high force capabilities to recruit, orient, and utilize their force in more meaningful ways. Conversely, in my experience, poor movement and high forces have been recipes for disaster when it comes to unfavorable situations regarding hamstring injuries, shin splints, sub-optimal performances, and the like.

I have seen many schools of thought on social media try to discredit the importance of movement in overall performance; however, I just can’t see a situation where teaching an athlete to move like the fastest athletes in the world is detrimental. In my opinion, you need to learn the rules of sprinting prior to breaking them.

I just can’t see a situation where teaching an athlete to move like the fastest athletes in the world is detrimental. You need to learn the rules of sprinting prior to breaking them. Share on XHelp an athlete enhance their mastery of sprint technique and understanding of when to apply it, as this is a useful tool for them to have. For example, in team sports we hear a lot about how athletes rarely hit max speed positions that resemble elite sprinting in games. While I agree to an extent, there are times that having that ability is beneficial, especially as it pertains to making open field plays or breaking free against a defense. When in traffic, it is useful to have lower heel recovery, lower knees, and a generally lower center of mass as an athlete reads and reacts to an ever-changing situation. However, once the athlete has made their way out of traffic and has daylight to run, elite top speed mechanics would likely benefit the athlete more to break away rather than the stereotypical team sport movement patterns.

Video 1. While keeping an eye on movements live is effective and meaningful, being able to break down video of an athlete is critical. Not just to understand their habits, but video analysis can also help you determine potential sources of movement insufficiencies and direct your interventions.

3. A Supportive Environment

I attribute a lot of my personal success at both the high school and college levels to a training environment that was conducive to success. Successes were framed in a way that inspired me to keep working hard to improve, whereas things that may usually be seen as failures were presented by the coaches as opportunities to reflect, learn, and grow. My high school coach sent me a message after tearing my ACL and hitting rock bottom: “The way you handle adversity defines your character, you’ve got this!” This type of training environment has a reach that is greater than any single or group of training days. It extends to the person an understanding that while training in most locations is simply a sheet of paper or set of ideas that are tactfully implemented, there is more that goes into the training equation than just doing work, recovering, and repeating.

Athletes are humans with everyday issues like the rest of us, and these issues may manifest outside or within a given training session. This includes problems at home, school stresses, relationship problems, lingering injuries, social disparities, and much more, along with the pressures to perform well every day on their shoulders. Understanding how these complex experiences interact to disrupt sleep, diet, intent, motivation, execution, and other aspects of training may help you provide support in a more meaningful way to really bring out the best in your athletes in the face of all of these potential barriers.

Support does not have to be verbal but being able to read the room and having the ability to adjust your programming on the fly may prove to be more valuable than you might think. A good example is when an athlete clearly lacks energy, is unfocused, and seems tentative or distant. While asking probing questions may be beyond your comfort level, you can certainly adjust intensity, rest durations, overall volume, and the general content of the program to accommodate. You may be surprised at how well they respond to this approach.

Emulating this type of empathic, humanistic approach is very fulfilling and has been one of the biggest staples in my program for what I consider to be success. Surely there are a million ways to approach these delicate situations, and different coaches may feel more comfortable using one approach versus another. I think simply being aware and making safe, easily applicable adjustments in these circumstances will be beneficial to the athlete in some way.

4. Data Collection

The athlete-centered approach I take has led me to develop new ways to frame the training process for the athlete. While it is clear that the goal of training is to improve personal bests and peak performance, I also feel it is important to be consistently competitive with yourself on any given day of training. What I mean here is that while we are raising the ceiling, sometimes athletes can be consumed by the pursuit of hitting personal bests and, eventually, failure to do so may result in a negative sense of self.

I went in-depth on this in my previous article, but the premise is essentially that we can use data to change the athlete’s perception of what constitutes success, concern, and failure. While some may not consider these mindsets to be very important, I would argue that everything that precedes movement is influenced positively, neutrally, or negatively by the psychological state of mind, including things such as self-competence, self-efficacy, self-worth, excitement, motivation, and much more.

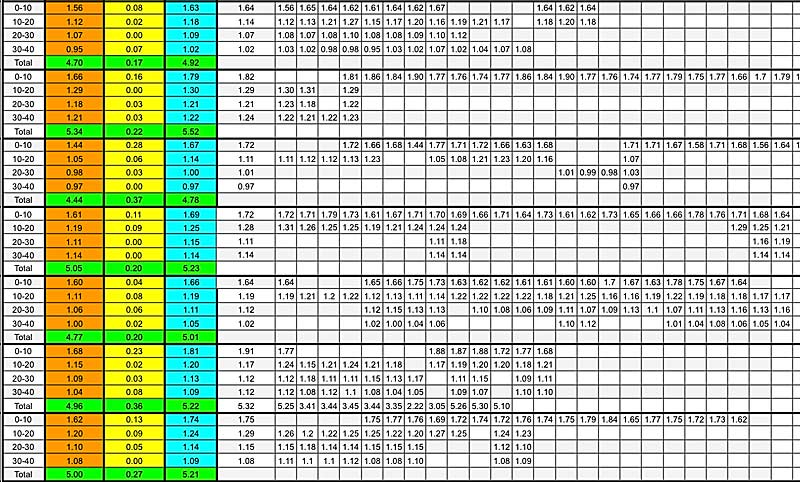

This is why I began to track rolling averages in addition to personal bests. When an athlete produces marks in training that are consistently above their rolling average, the personal bests will take care of themselves. The training progression is not linear, which is okay. Helping athletes understand that performances will ebb and flow has helped me keep overall intent, motivation, and performance levels high while also earning athletes’ trust in the process.

When an athlete produces marks in training that are consistently above their rolling average, the personal bests will take care of themselves, says @BrendanThompsn. Share on XCelebrate all personal bests, but be sure to also celebrate those who consistently perform above the bar that they’ve set for themselves. More opportunities, along with wider windows for success, have helped my athletes have more positive training experiences overall along with improved psychological states throughout.

5. Adaptability

During any given session I monitor several things with each athlete to decide how to proceed with them individually or as a group. Sometimes this consists of 0- to 10-yard starts, jump testing, medicine ball throws, or just an eye test in general. As the data rolls in, I can compare it to their averages to understand more about their current state of performance as it stacks up with previous days, weeks, and months of information.

If it trends above their rolling average, I can continue things as planned and assume that the athlete is in a good physical state to perform that day. If the trends go in the wrong direction, I should be fluid in my plan for that day and opt for something with lower intensity and less volume and figure out how I’m going to make that day productive without negative consequences.

To me, low trends might indicate an athlete is sore, fatigued, burnt out, or having issues outside of the session. Some of these issues may consist of their diet, stress levels, sleep patterns, or other influences that may contribute to their relatively lower outputs. While there is nothing on any given training day that is going to exponentially accelerate the progress of performance, there are an infinite number of things that can totally derail any progression that may be occurring. In the end, it is not worth pushing an athlete to their limit when they are in this physical state. There is much more to be lost than gained in these situations, and in my experience, it is more beneficial to opt for a “less is more” approach to combat what I see.

If the athlete is not ready to adapt to the training stimulus for the day, you may cast them further into a training deficit and prolong their eventual recovery and subsequent readiness to train at a high level. The CNS may just need an additional day of lower workloads or to take time away completely in order to bounce back. While this might be frustrating for the athlete, I believe it lowers the risk of injury and prevents more long-term training complications.

6. Self-Reflection

Many coaches have what they call the “bread and butter” of their program. What I mean by this is there are typically a few aspects of training that are staples in a given program and are uncompromisable and irreplaceable. For me, those staples include improving maximum speed, acceleration capabilities, movement economy, and overall power, among a few other things. Another concept that is important to me is pursuing the minimal effective dose in training the athletes I work with. I always look to maximize my return on investment, as I typically have very little time with them to work on various things.

A pitfall I eventually ran into was continuing to invest time into things that yielded diminishing returns. At one point, athletes coming to my sessions knew that they would either be doing fly 10-yard sprints or 40-yard dashes along with an array of other things on any given day. When the time I invested in this training structure began to show a plateau in results, I was stubborn and continued to implement the same training strategies over and over. I mean, these were my staples! This is what I was known for! Surely compromising these aspects of programming would be too costly to my identity. It was a difficult situation to navigate.

and helps increase the resolution of the training process.

Eventually I was able to see that even though these metrics are extremely valuable, there may be a better use of time in other domains that would still complement the important qualities I was after. We still sprinted at high intensities and frequently, but I had to scrap my simplified approach because athletes were hitting a wall. I thought to myself that the emphasis had to change periodically, similar to the way that we see many coaches periodize programming in the weight room. What I mean by this is that I began changing the overarching themes so that all of my eggs weren’t in one or two baskets all the time.

Had I not possessed the ability to admit I was wrong, my athletes would have wasted time pouring their hearts and souls into workouts that were not yielding the results they used to. Share on XBy cycling through various themes and training densities, accessory components to speed began to improve along with speed itself. This isn’t to say I’ve gotten away from max sprinting, just that I’ve decided to complement the max speed work with other components. I’ve found that when training athletes this way, they tend to tolerate greater volumes of high-quality training while also improving beyond the plateau we seemed to hit with a relatively one-dimensional approach.

Understanding that my niche approach wasn’t universally applicable was the first step in addressing this issue. Initially, it hurt my pride to change my approach, but now I hold very strong feelings about self-reflection and using it frequently to grow. Had I not possessed the ability to admit I was wrong, my athletes would have continued to beat their heads against the wall as they wasted time pouring their hearts and souls into workouts that were not yielding the results they used to.

Develop Your Own Principles

These six principles have helped me become more well-rounded and mindful, and in tune with the athletes I work with, so that I can program in such a way that lays my ego aside in order to do what is best for them. It has helped me hold myself accountable and pushed me to continue evolving as athletes continue to come to me with unique circumstances and individual needs. Being able to identify these needs can be a challenging process but doing so allows me to prioritize certain elements of the training program to push the athlete in a meaningful direction.

I challenge you to come up with a handful of principles of your own that will push you to continue to grow and provide better training opportunities and experiences for the athletes you work with. Share on XI understand that these principles may not be universally applicable or practical for everybody, and that is okay. I challenge you to come up with a handful of principles of your own that will push you to continue to grow and provide better training opportunities and experiences for the athletes that you work with. Please share them with me if you do, as I know that I don’t have the perfect program, and there are valuable lessons to be learned from everyone. If you consistently stay informed and are able to choose a training approach that works for you and provides objective results for your athletes, I think you will be well on your way to success. There are many roads to Rome—never forget that!

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF