With the recent boom in technological advances, it is becoming increasingly common practice to use equipment that measures various aspects of athletic performance to follow progressions from baseline throughout the training process. Some of these metrics include velocity, timing, vertical jump height, distance, power output, bar path and bar speed, ground contact times, and much more.

The presence of these devices has been shown to increase intent and motivation, which positively affects performances in training, as athletes are in a perpetual state of chasing personal records in each measurable statistic. Many of these personal bests are then championed on social media by coaches and athletes from all over the world, whether in an attempt to advertise the effectiveness of their program, demonstrate principles of different programs sweeping social media, or in some cases, for trainers or coaches to “flex” their superiority over other coaches posting similar metrics for all to see.

While chasing personal bests has a great positive effect on performance, there are unintended and often undetected consequences of this approach to training, says @BrendanThompsn. Share on XAll personal bests deserve to be celebrated, and I applaud all of the coaches that do, regardless of their motive. What I will say, however, is that while chasing personal bests has a great positive effect on performance, there are unintended and often undetected consequences of this approach to training.

PR or Bust

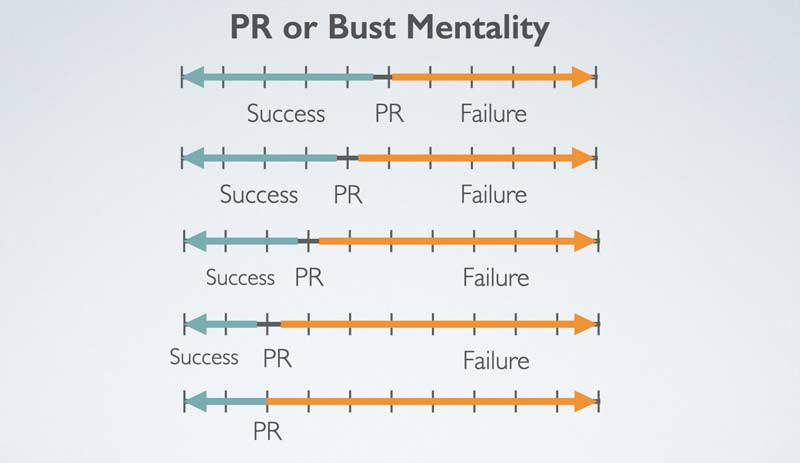

How many practices have large numbers of athletes who do not hit personal bests at all? How many whoo-hoos and hoorahs are distributed among those athletes? Must an athlete run a personal best to get that response from their coach? What about the athletes who follow their coaches on social media and never see their name mentioned because they don’t run personal bests at practice? Are these athletes now feeling undervalued in their respective programs because they aren’t good enough to earn celebrations either in practice or on social media? There may be personal bests for some athletes, but for the vast majority, running a personal best every day is not a sustainable reality.

The PR-or-bust mentality polarizes athlete responses to training and affects subsequent reps within the session as well as after. It also sets these athletes up to revolve their self-worth around this idea of absolute success or absolute failure. While at first glance this may not seem like a major issue, how many athletes run personal bests every single practice?

If an athlete ran a 0.01-second personal best every practice, they would eventually be faster than a cheetah and approach the speed of light. While it would be amazing if this was something we could achieve as humans, I don’t believe our anatomical structures or physiological capacities will be ready to produce those kinds of forces any time soon.

I take particular issue with this because I, too, fell victim to this PR-or-bust approach to training my athletes. I celebrated personal bests while chalking up “shortcomings” as something that I could not control. I convinced myself that it must be something athletes were doing outside of training that affected their performances.

While my inclination could have very well been true, it did not sit well with me to see my athletes leaving training sessions with their heads down in disappointment. After several weeks of reflecting on this issue, I began wondering if there was anything I could do in training to help resolve this unintended consequence of a culture that equates achievement with obtaining personal bests while carelessly leaving behind those who appear to have plateaued or regressed.

By only placing extreme emphasis on absolute maximum running and only measuring a couple of variables, such as the fly 10-yard sprint or the 40-yard dash, we severely limit opportunities for athletes to see growth. If they do not hit a personal best that day in either of those metrics, they are kind of left reeling and wondering what they did wrong to not be at their absolute best every single day.

By only placing extreme emphasis on absolute maximum running and only measuring a couple of variables, we severely limit opportunities for athletes to see growth, says @BrendanThompsn. Share on XI thought to myself that if I could create more opportunities to run personal bests, it would fix the issue and restore motivation, as well as perceived self-worth, at the conclusion of our sprint sessions. So, I started timing each segment of each rep.

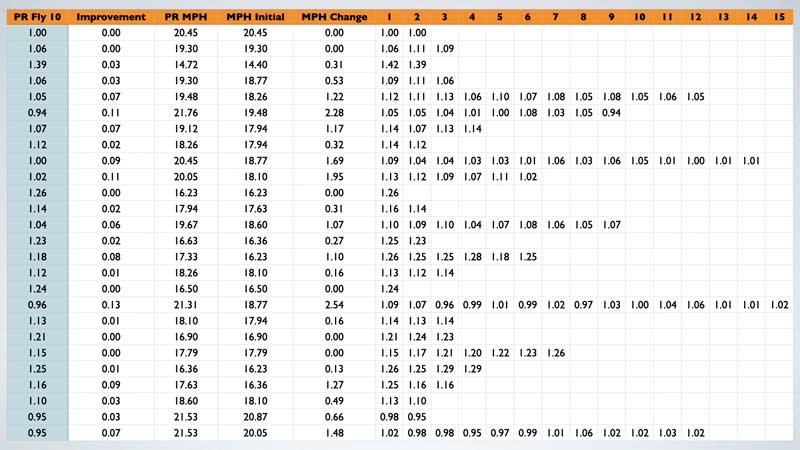

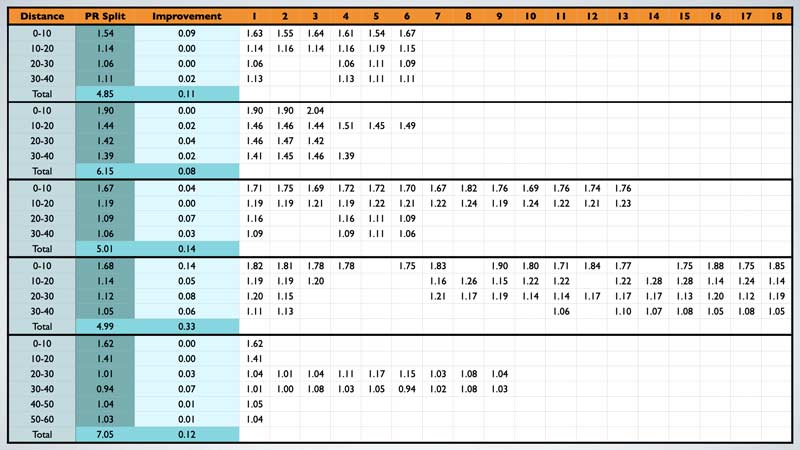

For example, a 2×20, 2×30, 2×40 would include Freelap data from each 10-yard segment of each rep, the total automatic time, and the total hand time. Initially, it worked, but eventually the athletes plateaued again. With that, their moods regressed, and the dopamine surges came less and less frequently. I was still conditioning them to behave in this fashion by the way I structured my data collection, and this was now the most obvious issue that I needed to resolve.

What Comes Next?

We have now been timing our sprints for several months and the personal bests have stopped coming. The excitement and joy associated with the novelty of timing and intrinsic competitiveness have begun to deteriorate. The athletes have regressed below their baseline levels of intent, motivation, and dopamine responses. The smiling faces and high-fives have diminished because their sense of self-worth and achievement was so deeply rooted in these personal bests that were conditioned into them by their new culture of measuring.

As a coach, you may become frustrated and question what you did wrong. You measured, you made it fun, you took out the fluff from your program to cater to your athletes, and you now wonder, “What do I do now? What comes next? How do we get back on track with all of these personal achievements and team positivity?”

Well, if we know speed is king, then we certainly shouldn’t stop sprinting, performing plyometrics, or measuring. But maybe there is something valuable that we aren’t measuring or including in our interpretation of the data that could give us more perspective on the situation. Eventually, I brainstormed a new way to collect and use data that may address these issues: the rolling average.

Discovering the Rolling Average Concept

The concept of the rolling average is not a new one, though I have not seen it broadcast all over social media the way I have seen personal bests and daily leaders. My thought process regarding this particular metric stemmed from a variety of things, the main one being that I needed to find a way to widen the window for perceived success in the athletes that I work with. I believed that accomplishing this would create not only more, but also bigger, opportunities for that coveted dopamine response that is frequently talked about in sports psychology.

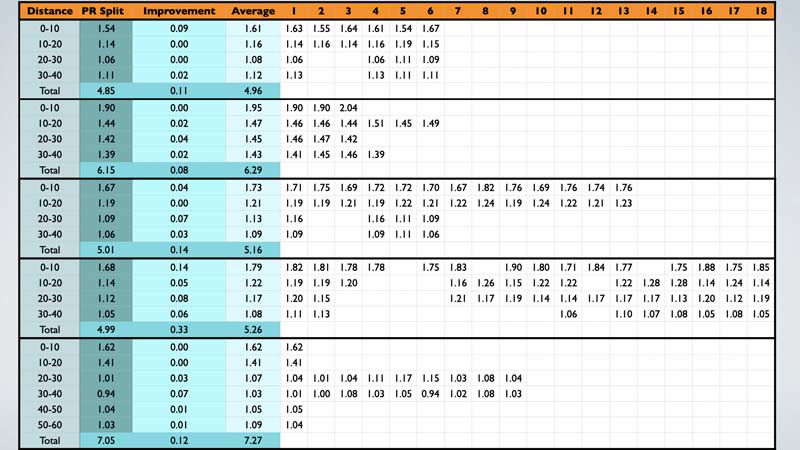

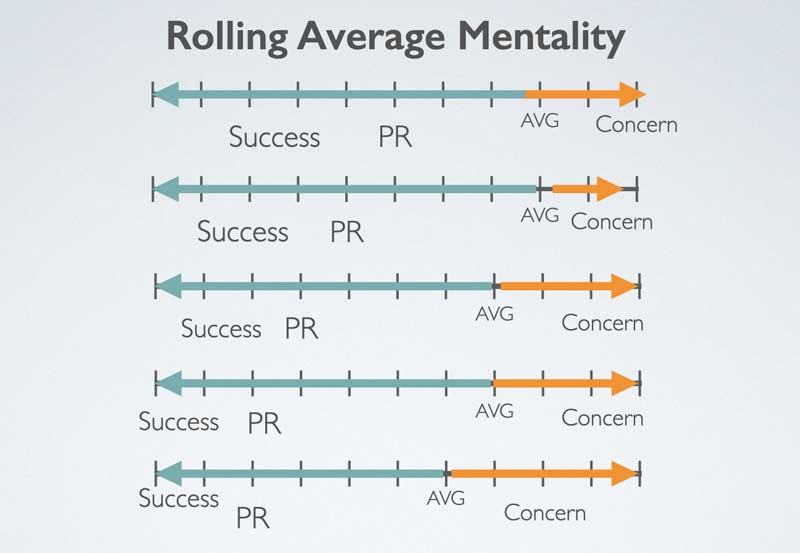

By using every available data point within a given time frame to create these rolling averages, we are not only better able to see where we have been, but also where we are going. For example, in the PR-or-bust data setup, I only included PR splits and improvement from baseline. On any given day when an athlete does not achieve a personal best, neither data point moves, and the athlete perceives that their performances have become stagnant or even regressed. Self-worth is jeopardized, and the athlete leaves with a looming sense of failure.

With the rolling average approach to training, I still track PR splits and improvement, but there is an added column for the rolling average for each metric in order to show the athlete their total body of work. Every single data point affects the rolling average, and the way it is influenced gives a more valuable snapshot as to what may be occurring in the training process. Before every training session, I read each athlete their current averages on each metric (0-10 yard, 10-20 yard, 20-30 yard, etc.) so that as soon as I give them their times, they know how it compares to what they’ve collectively done previously.

Every single data point affects the rolling average, and the way it is influenced gives a more valuable snapshot of what may be occurring in the training process, says @BrendanThompsn. Share on XYou may note a positive, negative, or neutral trend on any given day and throughout any number of days or weeks. A positive trend compared to the rolling average shows that the athlete is collectively better than they have been, and the training process may be working. A prolonged negative trend may indicate overtraining, tentativeness from potential soft tissue injuries, the training stimulus may not be enough, or that it is not working in general.

This would be a great time to introduce a deload phase or figure out whether you need to ramp the training stimulus up or down overall. Talk with the athlete about rest, recovery, nutrition, stress management, school, life, and other important factors in their lives that may be impacting their performance.

Remember, just as it is not feasible to improve PRs every single session, the trends of the rolling average may undulate throughout various training phases. During an intentional heavy loading phase, you may notice some of these metrics fall off a cliff—this is an expected response to a heavy stimulus. When you strategically deload following this heavy stimulus, you may notice that the trends are overwhelmingly positive. Again, this is expected, as adaptation to your heavy loading phase has now taken place and the athlete is collectively in a better position than they were previously.

Be sure to educate your athletes on these phenomena so they understand they are not getting worse, but these are expected outcomes given the training loads. Prefacing this will likely change their outlook when the measurements don’t show them what they are intrinsically wired to seek: personal improvement. This is another reason the rolling average is great, because when the PRs aren’t coming during these loading phases, the window for perceived improvement is wider, and they will still have opportunities to appreciate collective growth.

Comparing the Two Approaches

The premise behind only tracking and celebrating personal bests—while initially adequate, competitive, and fun—sets up the athlete for an eventual plateau and perceived regression, which may translate to feelings of self-doubt and failure. It also fails to track other positive changes that may be occurring on any given day, and that lack of information can make or break an athlete’s intent, motivation, and dopamine response, which is ironic given that this is exactly what we believe we are chasing by conducting our program in this manner.

The premise behind only tracking and celebrating personal bests sets the athlete up for an eventual plateau and perceived regression, which can lead to feelings of self-doubt and failure. Share on XRunning a personal best every session is unsustainable and unrealistic, and it creates a toxic culture that leaves those who are not improving isolated and searching for positivity in their training experience, while temporarily parading around those who have not yet hit that point in their training. The goal of training is always to raise the ceiling on competitive performances, but the process of doing so does not consist of a never-ending positive slope throughout. Additionally, because this approach is not sensitive to the trends of performance, it makes it impossible to make critical changes to programming for individual athletes. A one-size-fits-all approach to training may initially seem great because it is simple and easily applied, but it fails to help the individuals who do not respond well to a general training method.

By shifting to a rolling average approach, we begin to give more perspective on what the athletes have done and in which direction they are going. It creates a training environment that is more sensitive to measuring and effectively tracking all levels of improvement while also informing the athlete and the coach of trends that are occurring throughout. Coaches can then use this information to make changes to programming for individuals and allow for more specialized training to take place.

While I’ve only used the concept for athletes sprinting 60 yards or less, I believe this concept extrapolates well to many measurements obtained from training, which can then be used to influence prescription one way or the other. It effectively widens the window for perceived improvement and allows for more of the athletes you’re training to partake in their own personal victories—even the small ones such as running all reps on a given day 0.01 seconds faster than their rolling average.

This is not to say that this method of data collection is superior to any other, but I began to utilize it in order to gather more information about each individual’s training process and to inform me of whether training appears to be working. Another reason I shifted to this model was to decrease the frequency with which athletes were left feeling like they’d accomplished nothing. It is one thing to feel like you got a great workout in; it is another to have objective, measurable improvement during that workout.

Any good coach will be able to spin even the bad days in such a way that athletes feel like they had a successful day. However, by leaving out certain variables, we could miss out on what is occurring in the bigger picture. The less we measure, the fewer opportunities there are for this perception of success to occur. The more we measure, and how broadly we are able to measure, the more it not only creates more opportunities, but also widens the margin by which personal improvement is objectively obtainable.

In the event that improvement is not occurring, we are able to go back and see how long it has been this way. Is it a small blip in the otherwise relatively positive trend? Has it been consistently negative or neutral for several weeks? What have we done to address it to right the ship? What can we do moving forward to affect these trends and impact the performance trends in a positive way?

Bringing It All Together

So, I’ve now covered several bases regarding data collection and organization that may help contribute to a more sustainable training model, as well as a more realistic and positive experience for the athletes. Training performances wax and wane as the season progresses, and that is okay. Just be sure that you and your athletes are aware of these changes throughout training so that expectations meet reality and athletes aren’t left wondering why their performances aren’t constantly improving.

Additionally, being forward and transparent with your athlete in these circumstances will increase trust and buy-in and improve the coach-athlete relationship as training progresses in the future. As far as application goes, the recent surge in timing device availability and utility has shifted the training paradigm from what would have been considered a high-volume and submaximal approach to being more focused on low volume and absolute intensity. This may not be a popular opinion, but there is more to the training process than each approach in isolation.

This may not be a popular opinion, but there is more to the training process than each approach in isolation, says @BrendanThompsn. Share on XBy using the low-volume training/absolute maximal velocity approach, whether it be a fly 10-yard sprint or a 40-yard dash, we do great things such as maximizing speed and intent and creating a much more exciting practice environment. Another benefit to this level of training is that it frequently exposes the brain and the body to positions that are needed for maximum intensity sprinting. This is excellent when preparing for competitions, as when the time comes for you to compete at that level, your body easily calls on the movement patterns that you’ve hardwired for sprinting, and the CNS has been prepped and primed to fire at this level of intensity.

The potential pitfall is when the athlete becomes accustomed to clenching and fighting as hard as they can for these personal bests that they chase each and every day. While it is great to expose them to this intensity in training and use the timing systems to obtain this intensity and intrinsic desire to be better, there is a level of relaxation that must occur in sprinting to raise the ceiling on results. If an athlete gives it their all and fights to the finish on every rep, they may find it difficult to relax enough to achieve these higher levels of performance and improve the range at which they can comfortably train.

On top of this, there’s a tendency for the wheels to fall off beyond the desired distance. If I have an athlete sprint 20 yards into a fly 10-yard zone, they have programmed themselves to set 30 yards as the finish and put their all into that 30 yards—meaning there is nothing left to continue beyond that point. While great for training and testing, what happens on a big play in competition? Will their velocities significantly fall off after 30-40 yards, as we frequently see on television?

When the eventual plateau hits, where do we go from there? Is it possible to deload from a low-volume approach? Are we flexible enough to admit that we should be sprinting further (60- to 100-yard+ repetitions) occasionally to improve our ability to not only achieve top speed, but hold onto it and decrease the rate of deceleration? Are there ways we can alter the programming to improve, or do we just keep going at it in the hope of eventually having a breakthrough?

Using the high-volume training/lower-intensity approach builds a large aerobic base that allows the athlete to handle lower speeds for longer durations and improves the repeat sprint ability. The catch is that, because the athletes aren’t exposed to maximal speeds often enough, their ability to hold speed is negated by the fact that their max speed potential has not been obtained. So, while it is great that they can essentially run forever and be an ironman at practice, if they don’t maximize the speed component, they will still get burnt in races, games, meets, etc.

The other downfalls of this approach to training are the tendencies to overtrain athletes and contribute to burnout. Under extremes of this approach, you may notice athletes’ overall energy levels are diminished, their ability to run fast at all is dampened due to a chronic CNS volume overload, and they may eventually get overuse injuries and weakened immune systems or even lose their passion due to the nature of this monotonous style of training programming. There is also more to training than doing nothing but submaximal intensity training at high volumes every day.

Athletes have been successful at the highest level under each training approach, as well as some who strike a balance between the two. So, while great for preventing deceleration and having topped-out endurance for games and meets, the ability to maximize speed suffers, and therefore overall performance suffers as well. Additionally, because we don’t sprint often, the shapes that pertain to maximal sprinting are not easily hardwired into our movement patterns. When we go from submaximal training to the real thing, we may see an increased frequency of injuries due to poor movement, and the CNS is not primed to fire at that level.

As before, we must ask the question: Where do we go from here? Are we flexible enough in our ways that we allow for the implementation of more maximum speed work to counter these flaws? Do we allow for more rest days and active recovery days? Are we comfortable lowering the volume in favor of increasing intensity? Will it be okay to allow the athletes longer rest intervals between repetitions, or will it be too much of a culture shock to simply allow them to stand around to recover for the next rep? Can you see that there is a level of maximal speed qualities that needs to be obtained in order to achieve optimal performance beyond enduring the competition?

Interestingly enough, many coaches have had success with both approaches to training, but other coaches have questioned whether these training methods were sufficient or whether they could be improved upon by addition or subtraction. While training Carl Lewis, Tom Tellez had staples in his program that included 6x200m and other longer submaximal runs. Clyde Hart had success coaching with a quantity-to-quality approach. Tony Holler and his Feed the Cats program have had a lot of success with a “less is more approach.” All three coaches have had athletes achieve success on the biggest stages. Is it that the athletes fit their programming just right or that each approach is sufficient as it stands to produce similar results?

I propose finding a middle ground between them, or a sort of hybrid approach. I don’t mean to train at moderate intensities frequently, but rather, balancing the maximal work with the submaximal work in a meaningful way and tactfully choosing when measurement will benefit rather than take away from each. I’ll add that there is no right or wrong way to program as long as you build your program around the important qualities you want to improve in training, providing optimal recovery, and progressing the training in a realistic and meaningful way.

There is no right or wrong way to program as long as you build your program around the important qualities you want to improve in training, says @BrendanThompsn. Share on XI use this hybrid approach when training myself and my athletes, and it has appeared to be pretty effective thus far. I will go into different aspects of hybrid programming and how I choose to implement measurement within each.

Biomechanics

I base my approach to all training around the premise of efficient and optimized movement. While there are schools of thought that totally disregard movement, I believe that sports are based on a foundation of movement and neglecting that foundation imposes limitations on performance qualities while also at times subjecting athletes to greater risks of injury.

Measuring movement is tricky, as it is difficult to objectively quantify and determine which movements are faulty and which are compensations for the faults. However, with a trained eye, knowledge of various movement qualities, and slow-motion feedback, it is often easy to pick apart optimal versus suboptimal movement. I then use this information to figure out which cues, drills, plyometrics, and other exercises I’d like the athlete to perform to rewire the faulty movements and promote the qualities I’m seeking. This topic could be a whole article in itself, and I will save the nuances of movement for another time.

Plyometrics

Similar to the biomechanical aspect of my approach to training, I also look for faulty movement patterns that may present themselves in sprinting. I still use video feedback to find the faults and to inform my next steps with a particular athlete or group of athletes in a session. Additionally, plyometrics are great for complementing the focus of the training session.

For example, during an acceleration-themed session where horizontal displacement and rate of force production are key to success, I will pick and choose variations of certain plyometrics to incorporate to develop these traits. Similarly, for top speed days when vertical forces are more desired, I switch my plyometric orientation to developing vertical power and stiffness to transmit forces.

Do not simply do plyometrics just to do them—do them with a particular purpose in mind. If you cannot give a reason for them to be in your program, chances are you’re just doing “stuff.” We want to replace “stuff” where we can so that we can be more intentional in our programming. Again, this topic could be an article by itself, but I will cover that at another time.

Video 1. This video outlines one of the many faults you can find when analyzing the mechanical aspects of plyometrics. Something as simple as ankle stiffness can be the difference between quick, efficient ground striking and slow, prolonged ground contact times.

Running: Max Sprinting, Submax Sprinting, and Tempo Runs

This is fairly straightforward, but the balance seems to have been skewed somewhere along the way. Each aspect of running has its place in a training program and should be utilized based on the qualities you’re after. We have all heard the phrase “speed is king,” and programs have recently began shifting all of their attention in this direction. Maximal sprinting has great utility when athletes simply haven’t topped out their speedometers yet.

The concept of speed reserve is a powerful one, and raising the ceiling on maximum speed allows athletes to “cruise” in-game at submaximal speeds without the same cost of exertion as when they were slower. The higher you raise that ceiling, the faster the speeds you can sustain with less effort, which will then limit fatigue and improve repeat sprint ability in game.

The key to using max sprinting as a training modality is to chase not only the ability to obtain max speed, but also the ability to sustain it, says @BrendanThompsn. Share on XThe key to using max sprinting as a training modality is to chase not only the ability to obtain max speed, but also the ability to sustain it. Some good methods are to use variations of the 10-yard fly as well as the 30-yard fly to address both traits. Only addressing one of these traits does not always address the other, so setting aside time to do both is optimal.

Video 2. This is a 40-yard test given to one of my football athletes. The massive intent and desire to run fast times can at times cause athletes to overexert themselves and “tighten up” in an effort to run very fast. Sometimes, this motivation is enough to propel athletes to great performances; other times it may inhibit them.

If an athlete has suboptimal movement, chances are that max sprinting may not allow them to improve upon those qualities in a controlled manner. Because of that, you may utilize submax sprinting (~90-98% intensity) or even tempo runs (~70-80% intensity) to allow the athlete to home in on any new cues or skills they are trying to master. For submax sprinting (90-98% intensity) I choose not to time, as it changes the intent from movement economy to chasing times.

I personally find that video analysis is great to reinforce movements while tweaking insufficiencies as needed. The athlete shifts their perception of success from time to execution, and in my experience, the results they achieve seem to produce intrinsic feedback mechanisms that are similar to hitting personal bests. They’re excited to master or make progress in difficult concepts as they rewire lifelong movement habits that have been deeply programmed in their brains. It also allows them to focus on qualities such as speed endurance and special endurance that they may need, depending on the nuances of their respective sport.

You may find that athletes actually run faster when on a submax focus, as they allow themselves to relax and their movements become more fluid while sprinting, says @BrendanThompsn. Share on XYou may find that athletes actually run faster when on a submax focus, as they allow themselves to relax and their movements become more fluid while sprinting. It is interesting that even though we don’t typically make attempts at personal bests every day or even every week in the weight room but rather train submaximally, we still see the maxes go up on testing day. I think this often gets overlooked in sprinting in the idea that we can train below our personal bests regularly and intentionally while still having the potential to improve our max speed, speed endurance, and other important qualities in performance.

Video 3. Again, we see the use of initial video repetitions to identify mechanical faults that can then be corrected for with proper training approaches. Technical components of sprinting are more easily controlled in submax runs, as shown here.

As mentioned above, tempo running is great for focusing on the biomechanics of sprinting, but it is also useful in training comfortable rhythm, cadence, and pacing mechanisms. Pacing is the giveaway here, so we should use a timing device to ensure proper execution of this type of training. Tempo improves aerobic capacity and the ability to recover between sprints, as well the durability to repeat sprint and sustain performances when having to compete on back-to-back days.

There are also instances of athletes improving their max speeds and overall performances when getting a steady dose of tempo in their training. These instances are frequently argued as an athlete improving despite their training, while others are quick to say that it was because of their training. I believe, as always, that it depends on the context surrounding performance, and we should use that to lead the way on programming.

Autoregulation

Another way to use timing to inform training is through autoregulation, in which athletes continuously sprint and recover until their times begin to fall off x% from their baseline of the day. Doing so allows the athletes’ times to dictate the training dose for that day. Doing more reps beyond the drop-off point yields diminishing returns, as movement quality, muscle recruitment, and other important qualities drop off as well. Without timing, we are unable to determine this point, which could be the issue we see with the lack of timing systems in training environments, as coaches prescribe x amount of sprints no matter what and the athletes must get through it or face a harsh punishment of even more reps.

The Best of Both Worlds

The debate between endurance and max speed training seems to grace my timeline quite frequently. While each approach has its own pros and cons, I don’t think it is fair to say either is wrong, as there are heavily documented objective results supporting each method. Additionally, we need to understand that the instances of improvement under any of the above training methods do not serve as the rule, as there are often contextual circumstances left out. These include such factors as a multisport athlete versus a one-sport athlete, genetics, training age, and lifestyle choices, among other things that also play important roles in the way an athlete responds to a certain training stimulus.

Maximum intensity sprinting isn’t always ideal, just as overdosing on slow volume every day isn’t always ideal. While we cannot be certain whether a one-size-fits-all approach is out there, I think it is safe to pick and choose pieces of each to complement your program. I won’t stake a claim that this hybrid approach is the best, as I don’t think any approach has been found to always work for every athlete. However, I think it is safe to say that finding a balance between the two by alternating them in an A day (high-intensity) and B day (low-intensity) fashion may yield optimal and more well-rounded results, as you are getting the best of both worlds without ignoring any qualities that may exist between.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF