High school football strength and conditioning has come a long way over the last 5+ years, making great strides to become better, safer, and more effective. We are moving past the “death by squat”/mindless conditioning grinding that dominated the scene for so long. In fact, as the landscape at the NCAA level has shifted toward optimal, evidence-based training methods, this leaves high school football as the last arena (probably worldwide) where so much work is done that at best does not transfer and at worst greatly hinders performance.

There is one thought process that must be crushed for the transition to be complete for high school coaches: If “X” team has “Y” number of players that can lift “Z” amount of weight for a single rep on any or all exercises, then we will have a winning season. This idea does not play with most sports performance professionals, but it is slow to die among the football coaching community.

The team that has players who have developed a level of “strong enough” that they can execute at game speed will maximize the time they spend in the weight room more optimally than those who focus on 1RM load alone, with no concern for maximal velocity. What can we do to ensure that is how we approach our programming?

Leveling

The goal of every performance program should be maximum transfer to sport. Sometimes max strength is what is needed in that moment; other times it may be hypertrophy or power, mobility, and many other factors. What we aim to do in our program is chase adaptations, not exercises or numbers. Give the athlete what they need, when they need it, to chase optimal performance in a process of long-term athletic development.

We call this leveling—the process of developing a deep system of progression and regression that is intentional and driven by reverse engineering the specific adaptations that will maximize our key performance indicators (KPIs). Obviously, transfer is the key to any athletic development program. It’s a waste to spend time doing anything that doesn’t transfer or build a base for something that will transfer.

The biggest failure of any performance program is the gap between what athletes do in the weight room and what actually transfers to the field, says @YorkStrength17. Share on XThe general problem I still see at the high school level? That missing link. The biggest failure of any performance program is the gap between what athletes do in the weight room and what actually transfers to the field. We need to recognize that, as Yosef Johnson has said, “There is a point where getting stronger in the squat, the bench press or whatever; this isn’t going to help us anymore.”

Some will argue that high school level athletes can’t be strong enough. I would disagree and ask strong enough for what? If a 180-pound athlete can back squat 400 pounds, how much more will their field skills improve by getting to 420? Consider the resources spent to add that 20 pounds. I could give example after example, but my point is there.

Football players don’t need to be powerlifters, so why train them like that? Are the officials going to set a squat rack in the end zone and give the team with the best total a seven-point lead to open the game? That’s when I will concern myself with those 20 pounds. Until then? My concern is transfer of training and driving adaptations that will lead to optimal performance on the field.

Is strength a major factor? Obviously there needs to be a level of strength development that prepares the athlete for the rigors of a violent sport. But that return on investment will dwindle at some point. We need to really take a close look at our programming from a 4+ year view and prepare the athlete for strong enough and know what’s next.

Specific Adaptations to Imposed Demands

How and when we apply stress to our athletes is what impacts the adaptations their bodies create. That is where the SAID principle comes in. Our athletes will adapt to every stress we put on them, good or bad. A big part of what we do is understanding the demands of the sport and using that needs analysis to drive the optimal adaptations. Where do we want our athletes to be to be ready to compete at the varsity level, and how do we get them there?

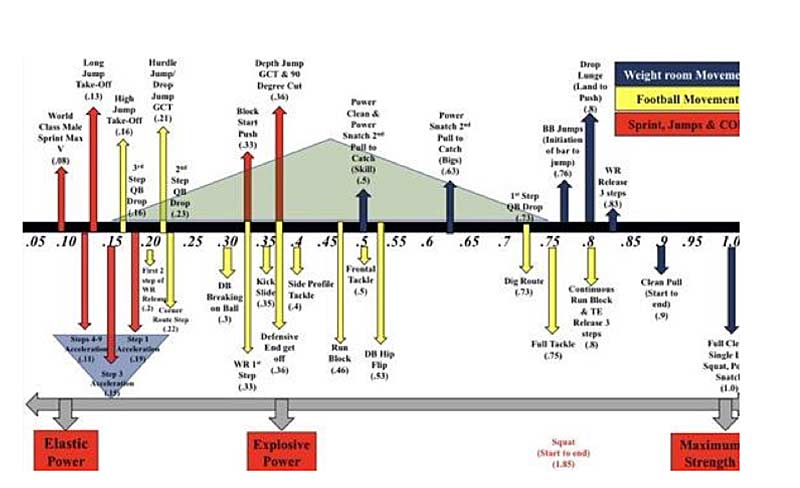

For us, the idea that dominates our end goal is the fact that all sports are rate limited. Sports skills happen within a certain time range. For example, David Ballou at Alabama has said they found the time between snap and contact for their lineman was 0.5 seconds or less. Coach Joey Guarascio at FAU has developed a chart that outlines his research of the rate limits for various football skills. These are examples of the time limits in which our athletes must express the strength they develop.

If your athletes can’t summon that strength and power in the time those skills happen on the field, then does it matter how strong they are in the weight room?

If your athletes can’t summon that strength and power in the time those skills happen on the field, then does it matter how strong they are in the weight room? asks @YorkStrength17. Share on XThe faster an athlete can perform the needed skills at the max power and velocity, the better chance they have of being successful. Power is the king of sport. Strength is without a doubt important, but it only transfers at game speed.

Will the team that can reach these thresholds always win the game? I don’t see any way to tie wins directly to any performance program. That’s unpopular to say, but truthful. There are simply too many factors in wins and losses that have nothing to do with what we do as a performance coach—most games are won by the team with the better players or lost by the team that made the most mistakes. It’s pretty simple, really.

It’s our job to help the athletes we work with reach their highest individual performance levels regardless of genetic ability. Our focus needs to be on passing the athletes along to the sport coaches in an optimal condition to physically perform their on-field duties and stay as healthy as possible.

Getting from A to Z

So, we know that the end goal is expressing strength and power within the limits of time presented by the sport skill. How do we go from a freshman athlete who has a serious strength disadvantage to a junior athlete who is not only strong enough to survive and thrive, but able to be explosive enough to win the individual battles that impact winning? The goals of our leveling program are:

- Build optimal movement skills.

- Add general strength to those skills.

- Teach optimal ground contact relationship in jumping to increase impulse.

- Slowly add depth to our strength/power/speed abilities.

- As the athlete advances up the levels, begin to transition toward more specific adaptations that will increase the ability to express our general strength and power development within the rate limits of the sport.

Beware of This Pitfall

The single greatest mistake I made early in my career was not knowing or understanding the pitfalls that surround moving athletes too quickly into heavy barbell training. This excerpt from Joel Smith’s book “Speed Strength” says it all:

“Excessive heavy barbell training, or even plyometric work, done early in an athlete’s career can decrease the sensitivity of the nervous system to the point where there is no coming back from that intense work for sustained improvements.”

I believe this is an epidemic at the high school level, and it interferes with the transfer of training for optimal development later in the athlete’s life. A mentor of mine has said countless times “Do you want the strongest 15-year-old football player or the healthiest, most skilled 17-year-old?” For me, that’s a no-brainer—I want a healthy and skilled older athlete with plenty of room for growth. If your athletes hit peak strength as sophomores, it may be a good idea to think about this concept.

Don’t overpay for strength adaptations. There will be a time when it will cost more for the athlete to adapt. There’s no good reason to spend that capital before that bill comes due. Share on XDon’t overpay for strength adaptations. Use the least complicated, lowest intensity protocols that will stress the athlete and drive the adaptation process. Why jump to 85% intensity when an athlete can still get stronger using 65%? Not to mention how much better their movement is likely to be at the lower intensity. There will be a time when it will cost more for the athlete to adapt. There is no good reason to spend that capital before that bill comes due.

Too Strong?

As I said before, I’ve heard the argument that a high school athlete can never be too strong. I generally agree with that, though I would counter but they can get to the point of strong enough where taking resources from strength development and placing them into other areas will increase transfer.

Strong enough for what? Optimal performance on the field.

They absolutely can get to that point, and there we need to begin shifting those resources toward more specific means of development. If the process of developing that level of strength interferes with motor skill development or makes the athlete less capable on the field, then we have failed that athlete. The tough part is that situation is individualized, and we often don’t recognize it until it passes, when it may be too late.

If the process of developing that level of strength interferes with motor skill development or makes the athlete less capable on the field, then we have failed that athlete, says @YorkStrength17. Share on XMy solution? Prepare for that moment as early as possible. Learn to recognize it not just by watching the KPIs but by watching them practice and play. This is the art of the coach’s eye. The place to start—which I learned by trial and error—is to not make “max strength” the primary focus of the program. Emphasize from early on that the program is athletic development in nature. Being better at the sport is the goal, not being better at lifting weights. Teach the coaches and athletes to chase the adaptations that will transfer the most to sport.

Transfer of Training

So how do we make sure we are doing everything we need to do?

Verkhoshansky explains that two factors lead to improvement in sports skill:

- An increase in the athlete’s functional capabilities (motor unit/skill threshold).

- An increase in the athlete’s ability to use these capabilities in training and competition.

“The training loads must have specific aims from a physiological, energy system, or functional standpoint.” – Verkhoshansky

The mistake being made is that instead of following these guidelines, many coaches (including myself early in my career) overfed the “max strength” monster and neglected all the other aspects of development. Instead, we need to figure out what “monster” needs feeding, when, how much, and at what cost, but neglecting none. Return on investment analysis from a time and needs based perspective is vital:

- What adaptations does my athletes need to increase transfer?

- In what step of the development process do I need to push each specific adaptation?

- What are the optimal amounts of these methods to sufficiently develop the athlete without undercooking or overcooking?

We have taken all these factors into consideration over the last few years at York Comprehensive High School. Here is our process for laying out the bones of the program.

- Develop KPIs that we believe will show us if our strength/speed/power programming is transferring to skill.

- Reverse engineer those KPIs to the most basic regressions.

- Develop a year-to-year plan of driving adaptations the athlete needs at each stage of development to successfully move to the next level.

- Set general goals we would like to see our athletes achieve based on normalized data collected over the years (as a soft target, not a standard).

- Begin with general and move to as specific as possible.

- Try to squeeze as much as possible out of each level of adaptation before we move on.

- Work toward the end goal of transfer to sport within rate limits in everything we do.

- Start athletes at 60% intensity for the majority of their volume in very basic movements and progress to 70–85% range for most volume using more advanced exercises with proficient technique.

Level Development

In previous articles, I laid out each of our levels in more depth. While we adjust constantly (e.g.: We use the 1×20 program with our freshman now, which is an adjustment made in the two years since this article was written), the basic philosophies of LTAD remain—these are the most basic aspects of each step. For a deeper look at each, please investigate the individual articles or reach out to me with questions:

- When to Add More Weight to the Bar

- Introducing Youth Athletes to Strength Training

- Transitioning Freshman Athletes to Your Strength Training Program

- Transforming a High School Novice into a Beginning Lifter

- How to Train Advanced to Intermediate Athletes

Each level is, in general, about a year. This timeline is very fluid and athlete dependent.

Level 0 – Based on Coach Joe Kenn’s “Block 0” philosophy, we generally begin this in the eighth grade. However, we are in the process of expanding this down to the sixth grade, which is an exciting prospect. Our focus here is the development of movement patterns and skills. Small-sided games, jumping and landing, basic skills. We will introduce them to our 1×20 program as well.

Level 1 – We begin our freshmen here, ideally in mid-summer. Our main movement goal is to have each athlete develop an optimal relationship with the ground. This revolves around teaching the delivering of maximal force into the ground both horizontally (early acceleration) and vertically (jumping). Strength development is the main adaptation focus. We will continue with the 1×20 program and eventually transition to 1×14 and 2×8 aspects of it.

Level 2 – This continues our progressions with a strength adaptation focus starting in the spring of ninth grade. We begin to use the more traditional barbell movements and introduce the 5×5 program with those. This is also where we begin to teach them APRE and eventually VBT within the 5×5 program.

Level 3 – This represents the highest level most of our athletes achieve. They start to use volume periodization and begin the process of transitioning to a more needs-based program that places athletes into buckets based on strength/power/volume needs. This level is where we begin to see our athletes hit the “strong enough” realm and we begin to shift to a strength-speed/speed-strength focus.

Level 4 – Our “super-advanced” level, which our dependable, high-level athletes can earn their way into. This group is traditionally very small, and we program a more highly individualized training session. For example, we will progress certain movements based on power outputs.

Level 3 and 4 is where our training sessions emphasize increasing the rate of force development and decreasing ground contact times. We also use VBT to increase intent and maximize power output and bar speed, regardless of load. The overall goal of the program is to build a vertical progression that will take our athletes from a basic strength development emphasis to a place where everything we do has the end goal of increasing the speed limits on the neuromuscular highways.

Patience and Progress

Overall, the thought process behind our program is based on the slow-cooking concept. We want to move our athletes as slowly as possible through each adaptation yet have them play within the rate limits of their sport. To do this, we must force ourselves to be patient. Too many times I have lost patience and pushed ahead too fast, giving us immediate improvements at the cost of net gain over time.

While this is a mistake, it is also an all-too-common occurrence in the field of high school strength and conditioning. Go for the next adaptation level only after the previous one is done. This is the most difficult aspect, and it is impossible if your sport coach is not on the same page.

Go for the next adaptation level only after the previous one is done. This is the most difficult aspect, and it is impossible if your sport coach is not on the same page, says @YorkStrength17. Share on XAdd depth to each progression with the use of tempo, isometrics, and ranges before moving on. Fight the urge to train heavy too soon and instead use tempo and time under tension to add intensity.

We use technology in many of our KPIs (what we use from a KPI standpoint would be an entire article, which I will write at another time). I purposely didn’t list our KPIs because it is important for each coach to develop their own process based on their individual situation. The point is to develop these indicators and then reverse engineer them to the most basic aspects of your program goals. Then, develop your progressions and go.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

1. Guarascio J. What is the true expression of movement? in sports, time will always be the ultimate factor #knowthegame #movement pic.twitter.com/feihqdwvl5. Twitter. Published August 4, 2021. Accessed January 29, 2022.