Individualization is one of the hottest topics in the training world—every parent wants their athlete to have a custom program, every athlete wants a program only they are doing, and every coach wants to build into their programming more individualization than the next coach. The problem, though, is that there are only so many training methods to go around. You have undulating block, linear periodization, triphasic training, and others, but at the root of all of these programs is the same end goal: you want to make an athlete better.

There is always an optimal solution for training an athlete, and the key is to find that solution, says @kingashton1. Share on XThe question isn’t how many roads lead to Rome, it’s what’s the most efficient way to actually get there. There is always an optimal solution for training an athlete, and the key is to find that solution. Oftentimes, when trying to individualize programming to athletes, coaches become too caught up in building a vastly different program for each athlete and lose sight of the fact that they are trying to make that athlete better.

[adsanity align=’aligncenter’ id=9053]

Intake, Assessment, and Individualized Buckets

We mainly work with team sport athletes in my gym. Our solution for providing individualized programs without “over-individualizing” or wasting time creating a new program for every participant is to bucket athletes. Each bucket has a different goal, and is made up of general templates that match that training goal. The templates mean we’ve made most of the program already (and, of course, the templates can have minor alterations based on the athlete).

We first divide each athlete by their age into either our youth program, for athletes ages 8-12 years old, or our adult program, for athletes 13 and up. Then, we break those down further into the following buckets:

- Foundations

- Hypertrophy

- Strength 1

- Strength 2

- Power 1

- Power 2

Each of these programs moves from general to specific with each block. When moving from general to more specific, we look at key factors in sport such as energy systems used, specific joint angles that occur in play, planes of motion, and total volume of work encountered. For example, a progression of the squat could go as follows.

These are the main things that we look for in each bucket, but depending on an athlete’s injury history, position, or specific range of motion deficits, the programs can vary slightly within each bucket.

We use the following assessment process to determine which bucket to place each athlete into:

- Movement screen. We score our movement screen on a scale of 0-30, and each movement is directly transferrable to our programs. Rather than doing a table range of motion screen, we look at squatting, hinging, pressing, and other capabilities. The score on the movement screen then tells us whether an athlete needs to be in our Foundations bucket or not. Our number one priority is that an athlete moves well—if they can’t move, they can’t play, and they will be in our Foundations block until they prove they have the movement capabilities to move to our next program.

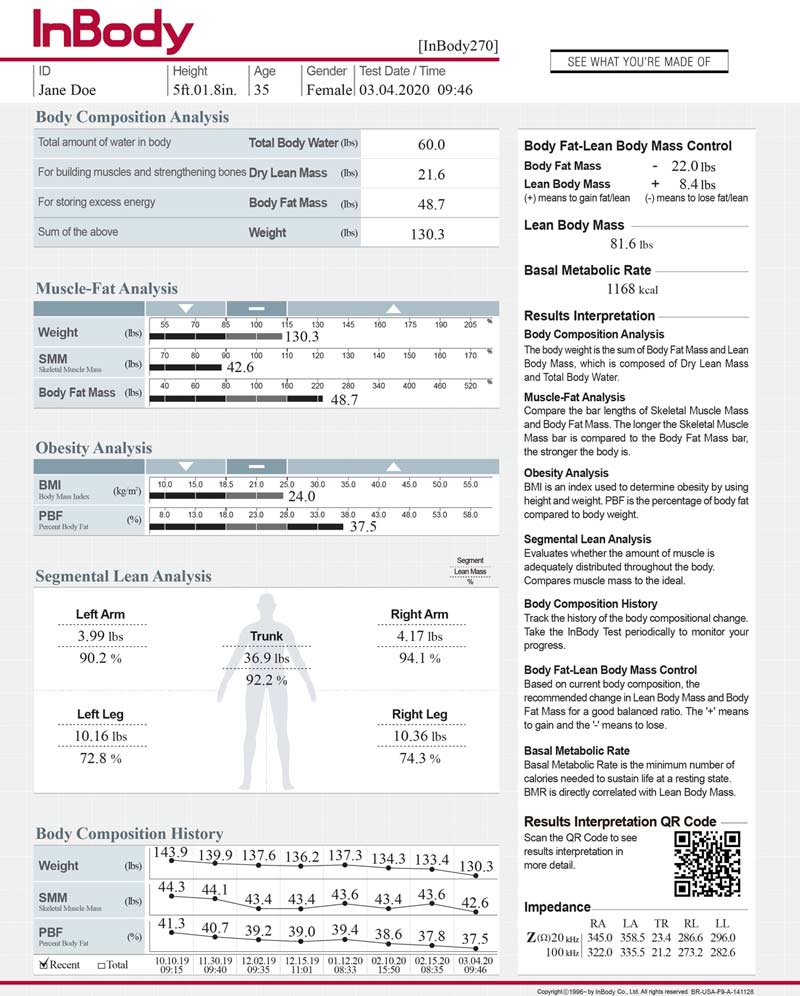

- Body composition. We determine metrics such as lean body mass, body fat percentage, and overall body weight. Then we compare this to where an athlete’s body composition needs to be to compete at a high level in their respective sport. This part of the assessment determines if an athlete will be in a hypertrophy block or not.

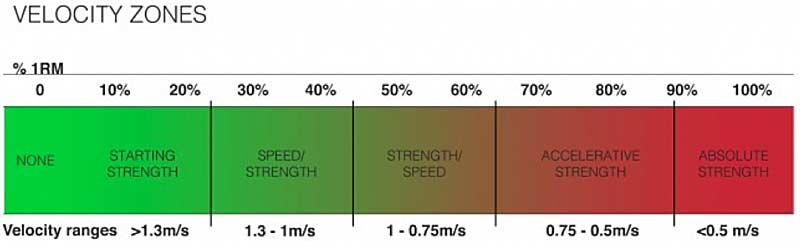

- Force-velocity profile. Using a Tendo unit, we have athletes perform various loads that allow us to predict an accurate one rep max, as well as their current force-velocity profile. We compare this projected max to specific strength KPIs that we have determined to be important in their respective sports. We can then also look at how their force-velocity profile is laid out and see if they are more of a force-biased athlete or a velocity-biased athlete. This is how we determine whether they will need to be in Strength 1, Strength 2, Power 1, or Power 2.

- Power screen. For this we look at qualities such as vertical jump, sprint times, and reactive strength index. This gives insight into how well an athlete transfers their weight room performance to on-field performance. It also gives us an idea as to how well an athlete utilizes their stretch-shortening cycle. Once we complete the assessment process, we look at an athlete’s yearly training as well as their assessment results and determine the bucket that would suit them the best.

Foundations

The Foundations bucket is built around basic weight room movements. None of these are specific to sport, and the focus instead is on developing quality movements that we can then build on and start to load in the later stages of training. The only metric determining whether an athlete is put in Foundations or not is their movement screen score. If an athlete scores less than 21, we place them in Foundations; if they score higher, we move on to other parts of the assessment to determine what bucket they will be in.

Foundations is the primary training block for athletes in our youth program. Athletes with a younger training age or older athletes finishing a season may get a Foundations block that acts as a short deload period to prepare them for the blocks to come by patterning quality general movement. We have also programmed Foundations for our older athletes who are coming back from surgery as an accumulation phase before they get into more rigorous training.

[adsanity align=’aligncenter’ id=9049]

Hypertrophy

We often program our Hypertrophy phase for athletes with a lower training age or athletes who are farther away from competition. For example, with a baseball pitcher who is relatively high level but could benefit from some extra mass, December would be an ideal time for them to perform a quick, four-week hypertrophy block.

For placement in the Hypertrophy bucket, we look at two key assessment metrics: first their movement screen score, and second their InBody analysis. The InBody gives us metrics such as body fat, lean body mass, and overall body weight, and determines a segmental lean analysis.

We tend to keep our hypertrophy blocks shorter, as research shows that, past four weeks, athletes usually see more sarcoplasmic hypertrophy than myofibrillar hypertrophy. Sarcoplasmic hypertrophy is great for bodybuilders because it tends to make you look bigger. When training athletes, however, we look for myofibrillar hypertrophy, as we want to increase muscle density and strength rather than add unnecessary strength and size.

When programming hypertrophy, coaches also need to look at where you add the mass. For example, front squats have been shown to have more vastus medialis activation than back squats. Given this, it probably would not make a whole lot of sense to assign front squats to someone who wants to sprint faster. Back squats would be a more advantageous choice in this case because additional vastus medialis hypertrophy would create a less-efficient lever when sprinting. These are the types of factors we consider as we progress from the least specific block in foundations to a slightly more specific block in hypertrophy.

Strength 1

Strength 1 is all about creating as much force as possible. Given this, we program all bilateral compound lifts with some unilateral accessory work. For programming in Strength 1 and Strength 2, we look at the two metrics that we looked at in hypertrophy, as well as the force-velocity profile.

Research shows that athletes are able to produce the most force bilaterally; because of this, athletes with large strength deficits will most often be in a Strength 1 block, assuming their movement screen and InBody metrics are sufficient. In Strength 1, we give athletes programs centered on basic strength models such as a 5/3/1 loading scheme. In the later stages of Strength 1, we also introduce athletes to tempos on the eccentric and isometric phases of their compound lifts.

Strength 2

In our Strength 2 bucket, we mainly program unilateral compound exercises, as the joint angles are more specific to those the athletes would encounter in sport. Strength 2 would be an ideal block for an athlete who is already relatively strong and only needs to make slight strength gains. This bucket allows that athlete to train at more specific joint angles, as well as generate the strength adaptations they need.

Additionally, in both Strength 1 and Strength 2, we break athletes further down into position groups. We then divide these into overhead and non-overhead athletes in Strength 1, and overhead, non-overhead, and bigs in Strength 2. The difference between the two groups is slight, but still important. For example, a football quarterback may get some more prehab-type accessory work for their shoulder, while a lineman might get more hypertrophy-based accessory work.

Remember, in this bucket, compounds are unilateral in nature. Overhead and non-overhead athletes would both perform split squats because that joint angle is similar to sport. However, this is not the case for someone in the bigs program; linemen are often in more of a staggered stance than a split stance, and programming staggered stance trap bar deadlifts would reflect this.

We also get slightly more advanced on the loading schemes and periodization models in Strength 2. As with Strength 1, athletes get some specific tempos such as a four-second eccentric or two-second isometric. In a Strength 2 block, athletes are introduced to methods such as an undulating weekly periodization model as well as the French contrast method. The reason for the more advanced training models is that, at this stage in training, athletes start to become better athletes; therefore, more advanced methods are required to create the correct adaptations and continue their progression.

Power 1

The Power 1 bucket focuses on training accelerative strength, strength speed, and power. When training in theses ranges, it is important to see the force-velocity curve as a spectrum rather than individual, clearly defined sections. Every athlete has their own specific makeup of fiber types; given that, peak power will come at a different load and velocity for each of them. Looking at the force-velocity curve as a spectrum, we can then cover different sections and ensure athletes have a robust power base.

Power 1 is broken down into the same position groups as Strength 2, and we also add in a strength-biased versus elastic-biased category. This is where an athlete’s reactive strength index section of the assessment comes into play. To perform at their highest level, athletes must be able to tap into their stretch-shortening cycle. If an athlete is strength-biased, their plyometric work would be more elastic in nature: hurdle hops, continuous broad jumps, and other plyometrics that are similar. For an elastic-biased athlete, their plyometric programming might be seated box jumps, paused box jumps, and other plyometrics that minimize the elastic component. This, again, is a small progression from Strength 1 and Strength 2, and it gets slightly closer to sport.

Power 2

Power 2 actually has fewer categories than Power 1, since we don’t include a bigs section in Power 2. This bucket focuses on training speed strength and starting strength. (The athletes in our bigs category have no need for those qualities due to the sport they play, so there is no reason to have them in a Power 2 program.)

Our Power 2 program focuses on training speed strength and starting strength. It is as close to sport as you can get without playing the sport or simply sprinting, says @kingashton1. Share on XPower 2 programming comes as close to sport as you can get without playing the sport or simply sprinting. This bucket includes a lot of jumps, light medicine ball throws, and light resisted sprints. Power 2 is also the category that features the most overload or underload training for sport, such as weighted ball throws for quarterbacks, or underload shot put throwing. Power 2 is also the phase where we introduce the time parameter for sets rather than reps. This does two things:

- It places the emphasis on speed, both in the eccentric and concentric movements. (Because, last time I checked, you don’t have a four-second eccentric on the playing field. It’s most often rapid.)

- It adds in an autoregulation component. At this stage of training, athlete freshness is paramount because they are either in-season or getting ready to be.

With a time parameter, if the athlete’s CNS is fried from the day before, they will move slower and do fewer reps; if they feel great, they will move faster and do more reps. The key is simply a high level of intent on each exercise with each set. Athletes in a Power 2 block are often our most highly trained athletes—they know their way around the block at this point and have the mental capacity to give maximum effort and attention to each and every set.

The last real difference in Power 2 is the introduction of oscillatory training. Oscillatory training consists of small, rapid moves at a very specific joint angle. The distinction between high-level athletes and elite athletes is their ability to relax rather than contract their muscles. Oscillatory training teaches athletes to rapidly contract and relax antagonists, with their muscles in harmony. The most elite athletes in sport are the ones able to coordinate muscle contractions between their agonists and antagonists. Thus, it makes sense to train this quality in our block that resembles sport the most for athletes.

[adsanity align=’aligncenter’ id=9062]

Where Are They Now and Where Are They Going?

Many people argue that with novice athletes you can do just about anything and they will get better. For the most part, that is true; on the flip side, however, the more advanced an athlete gets, the better the methods must be for that athlete to improve. The task, then, is to figure out what is the best way for an athlete to improve in the short term, without taking away from their long-term development.

Take Reagan, for example, a freshman in high school who weighs 120 pounds and throws the shot put. Sure, you can give him the French contrast method three days a week with a six-second eccentric, and if he doesn’t end up hurt, he will be a hell of a lot stronger in the coming months. Then what? After six months of progress, where do you go from there? What else can you give him?

If you pull out all the stops with an undertrained athlete, either they will end up hurt or you can’t give them anything else once they plateau. Alternately, take Connor, an Olympic-caliber shot put thrower. Sure, you can give him the latest 3×10 program that you found on Google, and he will probably get bigger or stronger at some point. But is he really getting better at shot put?

This is the challenge with individualization: You want to ensure the program fits an athlete’s needs, but you also want to establish that you are setting them up for long-term development. The main questions a coach must answer are:

- Where are they now?

- Where do they need/want to be?

- When do they need to be there?

Once you ask these questions, you’ll have an idea of the work that needs to be done.

This is the challenge with individualization: You want to ensure the program fits an athlete’s needs but also establish that you are setting them up for long-term development, says @kingashton1. Share on XThe assessment and bucketing process is not an end-all, be-all; nor is it the only way to create individualized training programs. Coaches must still be able to reason their way through the process deductively and make sure their athletes are prepared for competition at the right time. However, using this method will allow coaches to be present on the training floor and coach their athletes on the execution of their programs.

The bucket system also gives coaches an objective benchmark for how their athletes are progressing throughout the course of the year (and year after year as well). Individuation is a great tool in a coach’s toolbox, but as with anything, too much can be a bad thing. With this process, a coach can ensure each athlete gets what they need, but it also keeps the coach in check as to not aim to get too “cute” with an athlete’s program.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF