[mashshare]

Let’s just admit it already: Quantifying exercise technique is really hard. This is one reason we love to look at kinetic variables in the weight room over kinematics. It’s simply an easier measure to understand how much load an athlete has on the bar versus how they performed the exercise and if they utilized the correct muscles within the strategy altogether. Obviously, as coaches we always attempt to influence this within the day-to-day training process, but get three coaches to watch the same exercise and you’ll likely have three different interpretations of technique and strategy.

Despite the difficulties in quantifying movement proficiency, we haven’t stopped trying. Movement screens and assessments have created a buzz within our industry for a long time. Like many of my peers, I’ve been a serial user since the day I got into the profession. But each time I implemented an assessment, the results never seemed to move the needle. More often than not, I was left frustrated and confused, eventually throwing my hands up as I questioned the efficacy of assessing altogether. Soon, I’d discard it completely, until the next big wave of proponents had me jumping back on the wagon.

I came to realize that I had undervalued, overlooked, and disregarded the use of assessments because I was using them for all the wrong reasons. Now I understand the benefits. Share on XWhat I came to realize is that I had undervalued, overlooked, and even disregarded the use of assessments because I was using them for all the wrong reasons. So, it’s time to address those reasons head-on and detail the benefits we have found by bringing back a formal movement assessment. It is my hope that these insights may positively impact you within your environment.

The Benefits of a Formal Movement Assessment

There are a variety of reasons for the utilization of a movement assessment, from improving communication and unity among your staff to improving your filter for complex movement. Here are eight of the most significant reasons to implement a movement assessment within your environment.

1. Establishes a Common Language Around Foundational Movement Among Your Staff

Having a quick way to create context with your colleagues is time- and energy-efficient. This enhances everything, from day-to-day general training conversations to the more formal discussions surrounding challenging cases with specific athletes. This point is enhanced with interns, as it is common practice to have multiple intern classes per year coming into our program. A movement assessment has been a great tool to save precious time in getting them to understand the attention to detail we believe necessary for movement proficiency. It’s also an important step to begin creating a common language to refer to moving forward.

2. Establishes a Common Language Among Strength and Conditioning and Sports Medicine Around Foundational Movement

This point cannot be emphasized enough when working with others due to the varying perspectives and biases we inherently carry into our everyday practice. This perspective provides the lens through which we see to train our athletes. But every lens is different, and this creates a challenge, as there is overlap in care among the same athletes when working in a team environment; most notably with the sports medicine staff. In order to navigate this overlap, it is useful to have a basis of understanding that can be cultivated through a movement assessment. This leads to a more detailed and a shared understanding of movement proficiency—something that we can all agree is important for optimizing athletic performance.

3. Trains Your Coaching Eye

A movement assessment has the ability to help you learn to be more reliable in the analysis of foundational movement and train your coaching eye. The scoring criteria intentionally limit options of what to look for. Limiting options is useful to reduce complexity and think more clearly and specifically about what you’re looking at. Doing so repeatedly establishes a consistent process, which can transcend the movements you are evaluating and help you on the floor in real time with other patterns. Improving our coaching eye is a never-ending endeavor, as we continuously work to improve our ability to see, interpret, and intervene with the complex behavior of movement.

Video 1. Very basic patterns like lifting the leg reveal more than just hamstring length, these are a direct window to motor control. Asymmetry is a very pragmatic clue to coaches if an athlete has a clear difference between legs.

This point is magnified when it comes to younger coaches and interns. When others work within your system and seek your guidance in learning it, it is your obligation to teach them the skills of detailed coaching. We have found no better way to teach movement and discuss technique than through a formalized assessment.

A movement assessment has the ability to help you learn to be more reliable in the analysis of foundational movement and train your coaching eye. Share on X4. Utilizing Objective Criteria Decreases Biases

Our foundational movement assessment is objective. You perform a movement pattern and then receive a score. Without objectives, we rely more on opinion and intuition. While these qualities are essential in everyday coaching practice, they have the potential to lead us astray. When we are able to establish a common understanding utilizing objective criteria, we are better able to think clearly and have more informed discussions with respect to foundational patterns. Those informed discussions could then lead to better interventions to support athlete development.

5. Demonstrates to Athletes That Technique Is Important

Performing a formal movement assessment demonstrates to athletes a core principle of our philosophy: Technique is important. When it comes to training athletes, what gets measured matters. If we only quantify loads on a bar or height in a jump during testing or training sessions, we send a very clear message about what matters to us. Highlighting movement strategies and creating a road map for improvement via targeted interventions puts the athlete at the center of their training plan around quality movement. I have found that objectivity within an athlete-centered training model creates the most successful long-term results and buy-in.

Video 2. Fundamental movements like lunging are great learning opportunities for coaches. Athletes who struggle with lunge patterns can be further screened to see if it’s a familiarization issue or true dysfunction.

6. Conveys How Athletes Change over Time

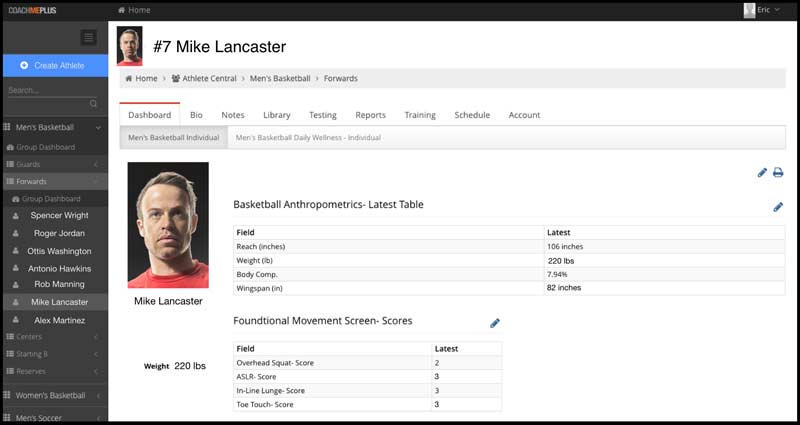

The assessment establishes baseline criteria for each athlete around their preferred strategy to accomplish movement tasks. Having objective baseline information is important when working with athletes long-term. Within the college setting, athletes will mature, grow, and develop continuously. We can then put this objective information into their “doctor’s chart”-like athlete profile within our system, along with the rest of their physical performance metrics, and give insight into how they change over time.

7. Establishes Baseline Movement Criteria in Return-to-Sport Cases

While we work tirelessly to reduce the occurrence and severity of sport-related injuries, it is a rare thing to find an athlete who plays at a high level and goes completely unscathed. Having objective baseline movement criteria becomes incredibly important following an injury in the return-to-sport process, as it can elucidate compensations, asymmetries, and their confidence in loading certain patterns.

Additionally, in my role as the strength and conditioning coach, I have a seat at the table with the support staff when discussing when an athlete will be physically ready to return to sport. This decision is often difficult and multilayered, especially if the injury was severe. I have found that the more objective the information I bring to that decision, the more confident I become that I am putting the athlete in the best possible position to return.

8. Improves Our Filter for Complex Movement

It can be said that what gets measured can be managed. We must measure and have a process in place ahead of time to manage the information we receive from our assessment. Dealing with complexity begins with putting defined borders in place, while acknowledging that the borders are just there to limit variance, collect data that actually means something, and manage that data within our environment.

Overall, the assessment criteria provide a filter that directs athletes toward a proper starting place in their loading progression for specific patterns within their training program. Share on XOverall, the assessment criteria provide a filter that directs athletes toward a proper starting place in their loading progression for specific patterns within their training program. It’s a direct line from assessment to program. This filter has the added benefit of catching the outliers in pain or asymmetries. It also gives us data in the form of clear and concise notes regarding why the athlete has failed to meet the movement standard and why they were scored the way they were. We can then use this data on the floor during actual training sessions to help guide athletes. Having these useful filters is critical and necessary when dealing with large volumes of people.

Why I’ve Thrown Out Movement Assessments in the Past

While the benefits have proven useful, it would be hypocritical of me to claim that I have consistently utilized the same formal movement assessment for prolonged periods of time. Before I was able to create our current assessment and subsequent process, I needed to address the reasons for those inconsistencies. This section outlines those reasons.

They take too long. Everything in our environment comes down to time cost. If it takes 10 minutes to perform an assessment on one athlete then, unfortunately, that time cost does not pay off. We are currently responsible for 450 athletes. A 10-minute assessment per athlete would be 75 hours of assessing. We also have to consider the inevitable class conflicts, illnesses, and other extraneous variables that come up when athletes miss the designated assessment session. This makes us unable to justify the time cost, both for the initial evaluation and the subsequent follow-up evaluations.

With time as our guide, we created an assessment that can be performed over the course of two days, taking the place of our typical performance prep for the day. The assessment takes less than 15 minutes by one coach for up to 25 athletes. Anyone who has ever worked within the college setting knows this is a tall task. In order to ensure efficiency, every single detail of the screen must be hashed out with precision.

They didn’t predict injuries. Not that they were ever supposed to. But when you connect the dots from identifying movement impairments to intervening on those impairments and making improvements, that statement seems logical enough. Injuries should decrease. Yet, I have come to realize that no one piece of information will ever be the holy grail in predicting anything. When it comes to injury, we know things such as previous injury history, structural evaluations, acute and chronic workloads, fitness level, technical proficiency of sporting movements, etc. must be considered to even begin having that conversation. Nonetheless, while the information may not establish risk, it does give us a data point that we may use to connect one more dot in our process.

I attached emotion to the results. It’s hard not to. As a strength and conditioning coach who believes movement proficiency is very high on the priority list, it takes a bit of undressing your ego to get over this one. I believe in my athletes moving well, having great technique on fundamental movements, and having a good understanding of foundational concepts with which they can become more self-sufficient.

A movement assessment really objectifies all those things. It uses foundational movements performed with body weight and minimal cueing requiring the athlete to understand and execute the movement. If my athletes scored lower, I felt this was a reflection of me failing them in one of those ways. Those views have changed quite significantly. Like a stoic philosopher, I try to view movement strategy with as little judgment as possible nowadays.

My athletes, and any human beings for that matter, are not machines that have function and dysfunction. There is no right or wrong way to move. There is no good or bad way to move. We utilize movement strategies that help us accomplish whatever tasks we are striving to accomplish. In this case, that task is the completion of some designated movement for an assessment purpose. How the athlete does so gives insight into how I may best load them in order to decrease collateral damage as much as possible, thus increasing the reward-to-risk ratio along the way in preparing them for sport. That is all.

The analogy I think of regarding a movement assessment is that it’s akin to an eye exam. We get our eyes checked annually in order to get the right prescription (and so we’re not a complete liability behind the wheel). Once we get the results of the exam, we are filtered to a prescription that enhances our vision. We don’t seem to get emotional about having to wear contacts or glasses like we do when one of our athletes scores a 1 on a squat screen.

When we go back to the eye doctor, chances are we will still need contacts the second time around. No big deal—prescribe accordingly and move on with life. We must remember that our perspective of the results determines the emotion we may attach to them. Scoring isn’t trying to establish if something is good or bad, right or wrong, functional or dysfunctional. It is just a first layer to improve our filters and understand what we are seeing.

Movement strategy is plastic and can change quickly, for reasons that have nothing to do with interventions that I can control. I realized that a lot of things impacted the way athletes moved, and these things came up every single time. When we assess, it’s just taking a snapshot in time. As we know, movement can be very plastic and change quickly. Sleep, soreness, time of day, warm-up, cueing, mood, etc. all have the ability to alter how the athlete may present that day. I wasn’t comfortable acknowledging that these factors would come into play each and every time I assessed. At some point, when you work in the real world, you consider the limitations, make a note of them, and move on. If we were to wait for perfect scenarios to evaluate our athletes, we wouldn’t have any data.

If we were to wait for perfect scenarios to evaluate our athletes, we wouldn’t have any data. Share on XWhen screens don’t filter you directly to loaded, trainable exercise progressions, it makes programming very hard. This is best explained with an example. If we perform a mobility screen for the glenohumeral joint in which the individual shows limitations and the suggested course of action is a contraindication of all overhead exercises, this makes things tricky from a training standpoint. This is especially true if the athletes being screened are overhead-dominant athletes for whom this avoidance of position would be a form of neglect. This neglect can be more damaging in its own right.

Video 3. One of the most popular screens is the overhead squat. While it’s obviously useful for snatching athletes, it’s an important overall squatting pattern that exposes movement incompetencies and joint limitations.

This example applies to all courses of action in which the results of a screen do not directly filter an athlete to a loaded, trainable exercise progression. My environment also requires me to write multiple programs for multiple teams all at once. Being responsible for that many moving parts becomes impossible without a straight line from assessment to trainable exercise. And while I must respect movement proficiency to the highest level, my job is to prepare athletes for the physical rigors of sport competition.

Video 4. Adding a heel raise reduces the demand for ankle mobility and adds even more information when compared to the basic overhead squat. Athletes who make large improvements in technique and have joint restrictions from past sprains can benefit from mobility prescriptions.

If the results of my screen aren’t aligned with my role within this, then it can cause more confusion than understanding. Our assessment takes you from the objective score to a trainable exercise directly. I elaborate upon this in detail in the upcoming sections.

What We Evaluate

All of the previous information provides context for both the benefits we’ve seen with a movement assessment and the reasons I’ve thrown them aside in the past. We have whittled down the movements that impact our training process the most. It goes without saying that this may not be what matters to you in your environment. I am completely fine with that.

An assessment, or really anything you do, should make sense to you in your environment. Share on XAn assessment, or really anything you do, should make sense to you in your environment. The goal is to solve your problems in ways that work for you and improve how you do business. While we believe there is merit in what we are looking at, if the movements don’t apply to you, use the framework and adapt things as necessary. But pay close attention to all the details involved, as the logistical problem-solving is equally as challenging as the formation of the assessment itself.

Video 5. The classic toe touch is simple and easy to administer. Athletes don’t need to be contortionists to be injury-free or perform, but motions such as this are gold for a quick appraisal. The end range of motion isn’t going to create a champion, but it will explain how they are restricted kinematically.

We are looking to understand our athletes’ strategies for accomplishing four foundational movement tasks utilizing only their body weight. These foundational movement tasks are:

- Bilateral squat via overhead squat

- Unilateral squat via in-line lunge

- Bilateral hinge via toe touch

- Unilateral hinge via active straight leg raise

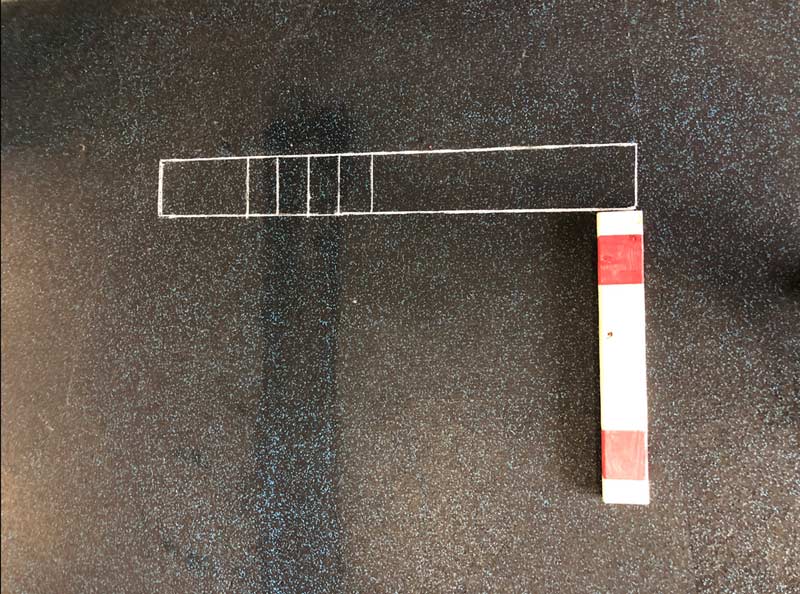

The individual setup utilizes a 2-foot board with two red painted stripes and a 4-foot chalk outline of a two-by-four that has five lines spaced 3 inches apart starting 9 inches from the front line.

During an assessment, we utilize four setups spaced 6–8 feet apart. We place a waiting cone 5 feet behind each designated assessment area, and then we walk down the line, assessing one athlete at a time. The monetary investment of all of this equipment is less than $10.

The scoring of the strategies of each foundational movement goes from 0–3. A score of 0 indicates that the pattern causes pain and a 3 indicates that the pattern was performed meeting all outlined objective criteria. With the exception of toe touch, for which we have created our own 0–3 scoring criteria, these are taken directly from the great work of Gray Cook and Lee Burton’s Functional Movement Screen.

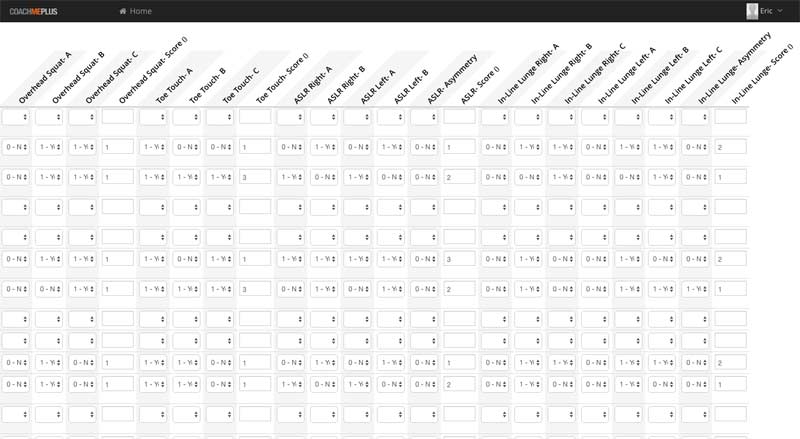

I present the scoring criteria and verbal instructions for each movement below. Featured is the actual scoring sheet utilized on the floor with our teams. As we assess each individual athlete, we read the instructions directly from the sheet. This minimizes time and energy and improves consistency.

Additionally, the number of repetitions assigned for each of the four movements aligns with the technical pieces we evaluate for that movement. For each rep, we look directly at one specific aspect of the movement to evaluate. For example, during the overhead squat assessment, there are three elements of the squat that we evaluate. These are: A) arms and torso parallel with tibia, B) femur below parallel, and C) knees aligned over feet. For rep 1, I look solely for the athlete to execute criteria A, for rep 2 I look for criteria B, and so on. This enhances the focus on one specific aspect of the movement. This also keeps personal bias from creeping in, as I often attempted to justify what I was seeing in real time. Both points increase reliability and save time and energy.

When recording the score on the sheet, there is an A, B, C, and score listed. When I watch an athlete perform the assessment, if they are unable to comply with the designated criteria, I simply mark the letter and move on. This allows me to understand which criteria they failed without having to take the time to make notes. Additionally, once athletes have completed all the repetitions, I simply circle the final score. Again, this improves reliability, saves time in writing out the score for each athlete, and saves the mental energy of thinking through all the reasons why I am seeing what I am.

You may think that these details are a bit over the top. If so, you’re probably right. You may not need to go to such great lengths for efficiency in your environment. But solving the logistics of my current environment is brutally hard work that I refer to as the dirty work. It isn’t so much about technical knowledge as it is taking technical knowledge and detailing every single piece of it to make it work. I cannot emphasize this point enough, as I believe this can hold us back from doing great things with challenging situations. It is my hope that the simplicity of this process does not discount its importance.

Next, we must consider the meaningfulness of the information we collect. As stated before, in order to be meaningful, it is crucial that the information collected is immediately relevant to our actual training process. The implications of that statement are enormous.

In order to be meaningful, it is crucial that the information collected is immediately relevant to our actual training process. Share on XThis is why we only evaluate the four movements that we do. In the past, I have been a victim of paralysis by analysis from looking at too many things all at once and not being able to connect the dots from screen to program. We assess squat and hinge movements because every athlete utilizes these movements in some form, and they require many subtle individual adjustments from athlete to athlete. Additionally, by evaluating only these four, we have been much more successful at looking beyond just these movements for other, seemingly unrelated, movements as well.

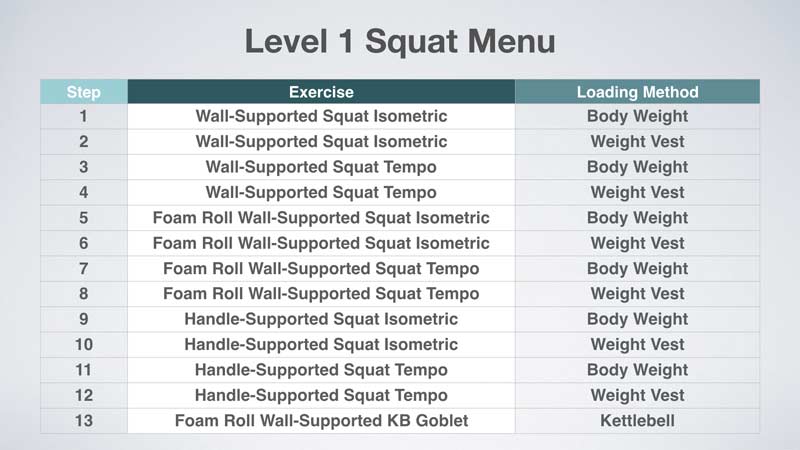

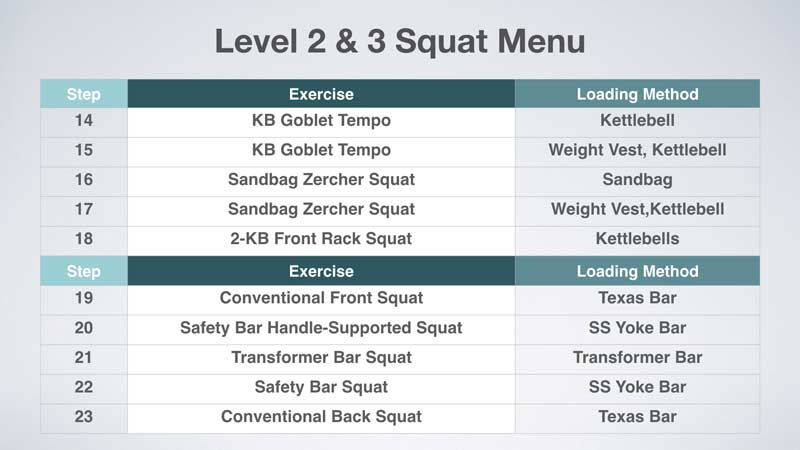

In order to know what to do with the information we collect, we must take the score and filter it to our exercise menu for each movement of bilateral and unilateral squat and hinge with designated levels from 1–3. For the purpose of this article, I have listed our squat exercise menu, which includes every version of squats we use.

When an athlete performs the overhead squat assessment, the score they receive gives them access to all the versions of squat for their score and below on their initial evaluation. It simply filters the athletes into buckets so we can establish that starting place. By having a designated squat movement in our lifting program, we can then have the athlete write their starting version directly on their sheet and guide the sets and reps accordingly. This can get them lifting that very same day, as opposed to sorting through all the different pieces of the assessment and attempting to connect the dots later on.

As stated previously, this filtering system improves our process immensely. We are much more likely to catch outliers before we get into more complex exercises, during which athletes may mask certain things. We also have a baseline objective score that we can refer back to as we load our athletes now and down the road. Both of these have been incredibly helpful, even with all of the acknowledged limitations.

A second point to address before moving on is how quickly we may progress an athlete forward within the exercise menu. For example, if an athlete scores a 1 on a screened movement and starts on level 1 of the menu progression, they rarely stay there for long. In fact, it is not uncommon to move the athlete forward that same day. This is where utilizing all the other contextual factors comes into play. Questions such as who is the athlete I am working with, what is their training age, what sport do they play, what time of year is it, what kinetic qualities are we after, etc., all become very relevant.

On top of that, we must acknowledge that exercises are skills that are task-specific and require different strategies to perform (this is yet another potential drawback of an assessment itself). The way we strategize to accomplish one exercise may be useful for “cleaning up” how the athlete performs the movement on the assessment. That being said, with this assessment I am still able to confidently run the volume of athletes I work with through my filter and catch outliers before they slip through the cracks.

Tweak the System as Needed

It is my hope that there are some points within this article that give you a new or refreshing perspective on movement assessments that improves what you do. At the end of the day, improving your own filters and processes and the training of your athletes is what matters most. More often than not, that requires some introspective analysis and problem-solving within your environment that forces you to tweak things to fit for you. There is no shame in realizing that someone’s system just doesn’t work for you exactly as proposed. It also doesn’t mean there is no value in that system.

There is no shame in realizing that someone’s system just doesn’t work for you exactly as proposed. It also doesn’t mean there is no value in that system. Share on XWhen it comes to movement assessments, I bet that the debates will rage on. Some people love them, and some people hate them. Some people will continue to love them, while some people will continue to hate them. As an industry, we have a tendency to polarize topics and swing the pendulum from side to side. When you’ve been at this a while, you will eventually see that pendulum settle somewhere in the middle as we realize that the opinions of both camps have some validity. For me, the pendulum of movement assessments has settled, as I believe in the value created irrespective of the shortcomings.

No one piece of information will ever tell the whole story. A movement score can’t tell you everything about movement. It can’t solve your injury problems or make your athletes better lifters in the weight room. There will always be more that you need to address and consider, but you need to see it for what it is. It’s another chapter in the story of an athlete who has value to bring to the conversation.

It is as objective and as unbiased as possible. It helps give context to discussions that become more meaningful and insightful, both to colleagues and athletes alike. It filters athletes to get them traveling down the right path in training quicker and safer so that you can get on with building monsters. And it supports your personal growth and development as a strength and conditioning coach.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

[mashshare]