In the last few years, breathing techniques have undergone a renaissance in the world of health and human performance. There is no shortage of social media bagpipes belting out what seems like the latest tunes in strength and conditioning. But when a tool as versatile as breath control presents itself, we have no choice but to listen.

Nasal breathing is an incredibly versatile tool that can enhance conditioning outcomes, create focus and resilience in athletes, provide novelty to training, and even serve as an insight into the CNS. Share on XNasal breathing is an incredibly versatile tool that can enhance conditioning outcomes, create focus and resilience in athletes, provide novelty to training, and even serve as an insight into the central nervous system. There’s a great deal of back and forth between opinionated coaches (is there any other kind?) on the inter-webs on whether or not you have to nasal breathe to get good performance outcomes in your athletes. As somebody who has been on the front lines of this work for the better part of a decade, let me clear it up right now—you don’t.

But—and this is a SirMixaLot-sized but—you will leave massive low-hanging fruit on the table for athletic development as well as general athlete health if you fail to understand the fundamental realities of this tool. The problem I see with the general way of approaching this topic at large is that it relegates performance to its outputs alone, and in so doing fails to enhance the precision processes.

You will leave massive low-hanging fruit on the table for athletic development as well as general athlete health if you fail to understand the fundamental realities of nasal breathing. Share on XFurthermore, this kind of shortsightedness fails to ask: what kind of problems can this tool solve and where could it fit in your toolkit? It’s my hope to provide some clarity and give coaches a sound justification for including nasal breathing in their repertoire, as well as clear suggestions on sensible applications that can be used as soon as you finish reading this article.

Health and How the System Works

Human beings have the ability to walk on both our hands and our feet—but if we have to walk a mile, walking on our feet is far more efficient for even the most skilled Cirque du Soleil hand-balancer. This is due to the fact that the anatomy of the foot and low leg has evolved to use ground force reactions to help conserve energy for forward propulsion.

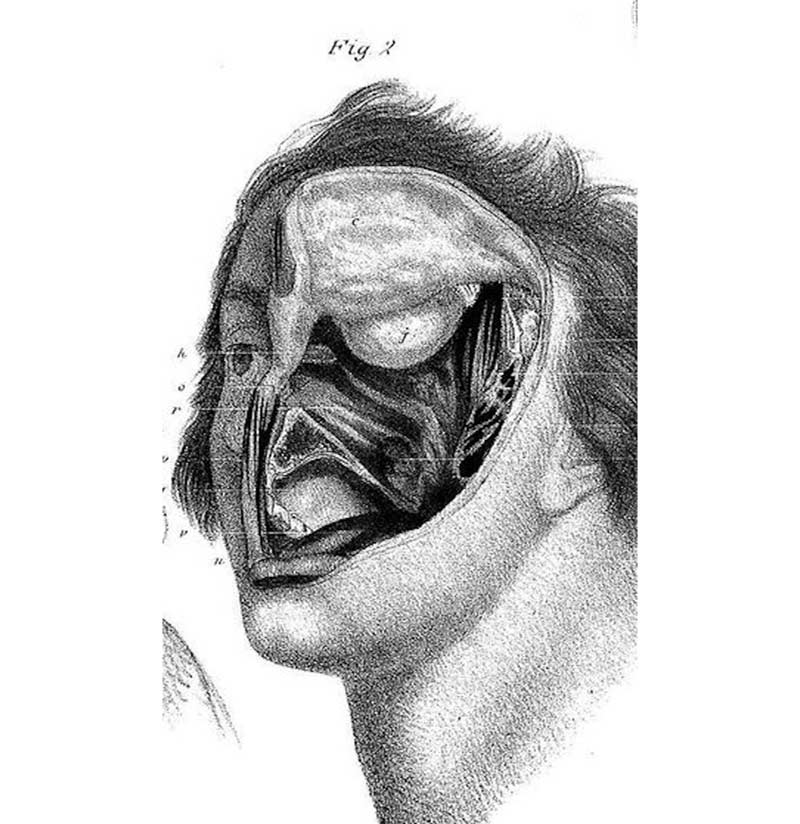

Similarly, both the nose and the mouth are capable of breathing, but the design of the nose is far better equipped to deal with air and offers layers upon layers of benefit. As such, the nose is the primary anatomical tool for ventilation in nearly all endeavors, and if it causes discomfort to do so, that’s not a design flaw of nature, it’s a health problem that requires resolution.

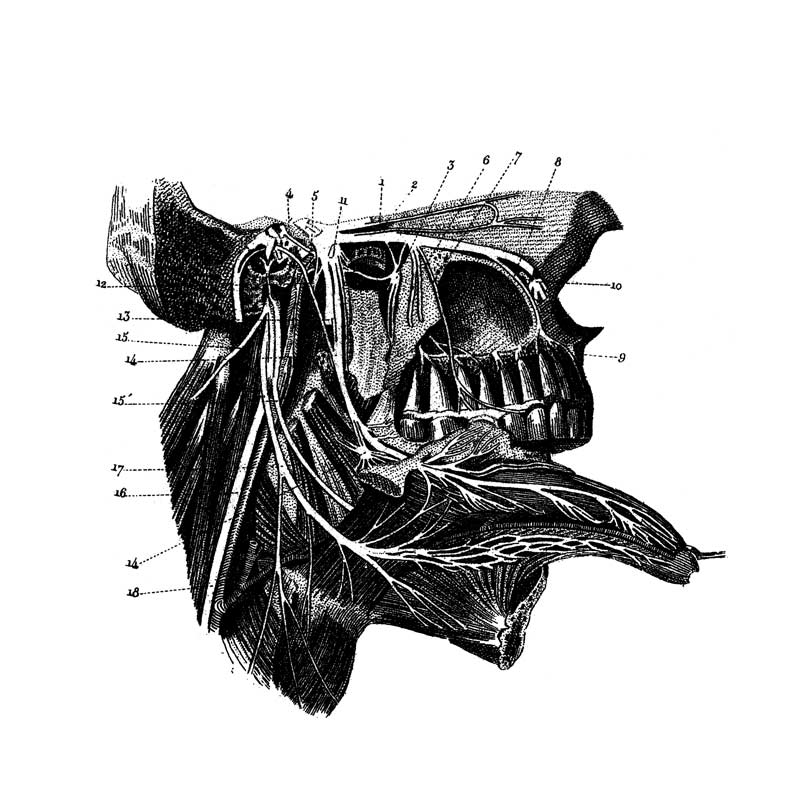

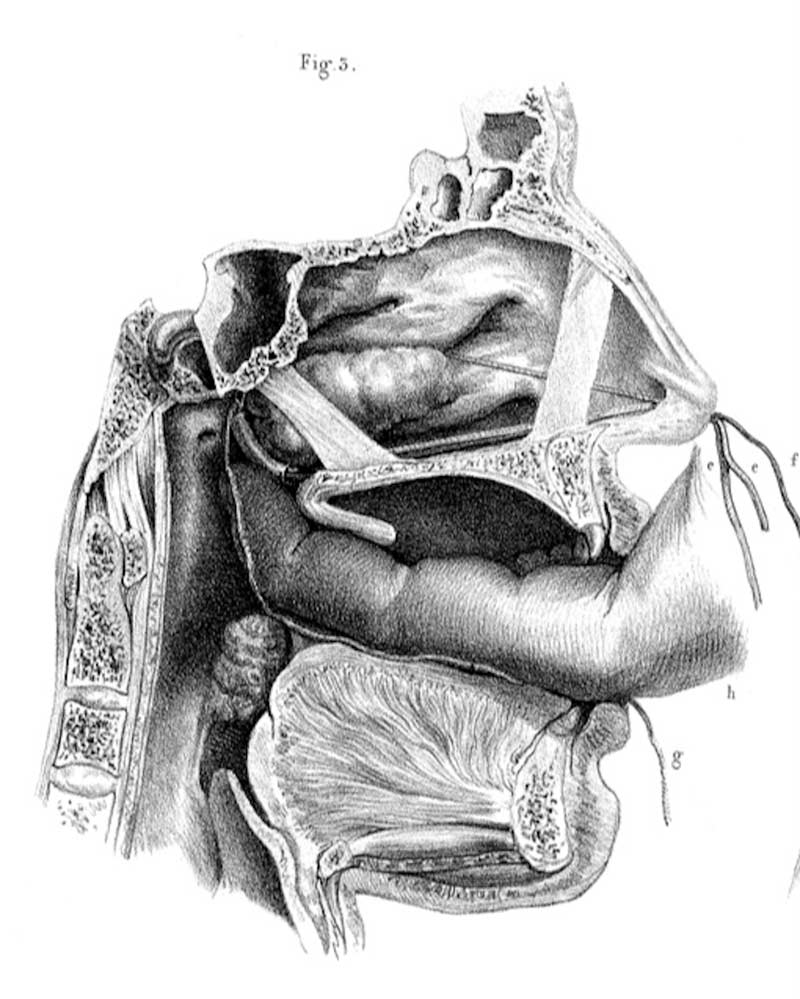

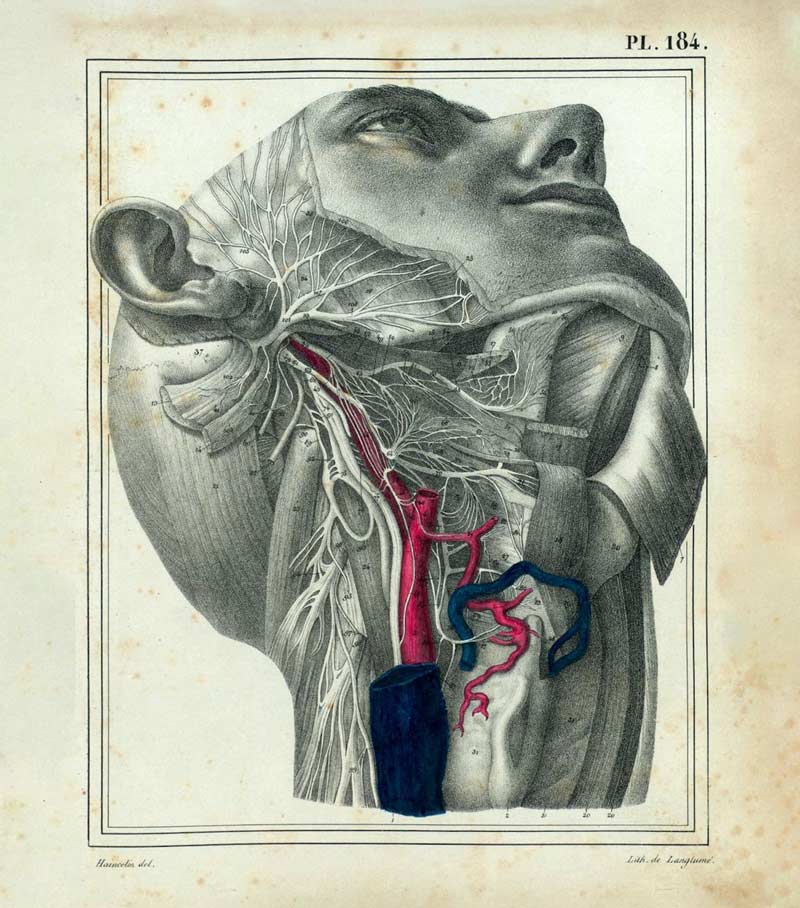

The nose and its functions are a complex and wonderful system of interrelated miracles that neutralize toxins, contribute to pulmonary function, and guide the formation of the face and jaw through pressure modulation. As one would expect in a complex biological system, when things go really right or really wrong, the ripple from the pebble goes far.

The nose is uniquely equipped to deal with incoming air: it has a filtration system that keeps particulate matter out of the lungs. (My wife and daughter think it’s funny that my personal filtration system is turning gray.) We have a system of mucosa and sinuses that are the ramparts against both bacterial and viral infections. The paranasal sinuses and their associated pressure are also uniquely responsible for the development and stability of craniofacial function and appearance, as well as having a direct impact on vestibular function.

The olfactory system also lives here, and besides the obvious job of regulating the senses of taste and smell, the olfactory system has deep ties to memory and other limbic system functions including the differentiation between safety and threat.

Additionally, nasal breathing provides twice the air flow resistance than that of the mouth and increases tidal volume in the lungs. This trains the diaphragm to become stronger and more pliable, which is an important outcome all on its own. The diaphragm plays an important role not just in respiration but in spinal stability through pressure modulation and is often co-indicated in back pain and instability issues. Controlled nasal breathing during work is a great way to get more bang for your buck and force the trunk to self-organize.

The nose is the primary anatomical tool for ventilation in nearly all endeavors and if it causes discomfort to do so, that’s not a design flaw of nature but a health problem that requires resolution. Share on XBreathing dysfunction is rampant in both non-athletes and athletes alike. Exercise-induced asthma and sleep apnea are found even among the studliest studs. You may be able to compensate your way to high performance, but believe you me, it is not sustainable, and biology will have the last laugh. Over time, respiratory dysfunction overtaxes the cardiovascular system, reduces sleep quality, and overloads other hormonal and organ systems. There probably won’t be a catastrophic disaster, but you’ll die from a thousand cuts.

Baseline health should be the foundation of human performance, and breathing—in particular, nasal breathing—is a crucial and often ignored component of a holistic performance approach.

Carbon Dioxide Tolerance

I would be remiss to write an article on nasal breathing and fail to mention the essential role carbon dioxide tolerance plays in the whole picture. It’s not within the scope of this article to go deep into this topic, so for now a brief overview will do.

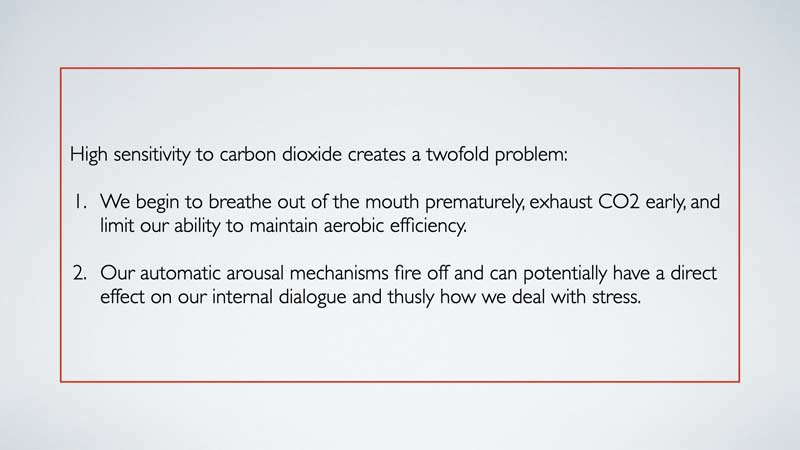

Contrary to popular belief, it’s not low oxygen that signals you to breathe—it’s carbon dioxide (CO2). There are very few sensors in human physiology that indicate low oxygen, but there are a ton of sensors for CO2. Why? Due to the very finite tolerance of pH of the human body. Too acidic? Coma, then death. Too alkaline? Coma, then death.

The body has many ways to regulate pH, but the most energy-efficient way is through the breath. Every breath we take is a management of these variables, and it never stops—especially not during exercise. There’s a feedback loop in the arterial systems (specifically the carotid bodies) that monitors pH and is the thermostat for both the volume and frequency with which you breathe.

When metabolic demands (real or perceived) go up, the system up-regulates the energy delivery mechanisms: heart rate and stroke volume, blood pressure, and, of course, breath rate. The rising levels of CO2 in the blood signal the body to breathe more through feedback loops in the autonomic nervous system. This autoregulation is generally a good thing, because as I mentioned earlier, it keeps us from dying.

However, if we use nasal breathing as an appropriately applied constraint, we can effectively improve general autonomic function and simultaneously improve the efficiency of energy metabolism both during and after work.

So, then, the big question is not really is nasal breathing necessary to improve performance? The question, rather, is how can it be intelligently applied to optimize results?

Practical Application

Nasal breathing can be used as a simple constraint in the training room for multiple effects. Practically, it’s an invaluable tool for use during general, low-to-moderate intensity conditioning, especially in aerobic conditioning that has a relatively low skill requirement.

As an example, a U17 rugby team from New Zealand I consulted with was looking for a way to incorporate breath awareness into their players. They’d tried a few different things up to that point, most of which were too complicated for a bunch of teenagers. I suggested the following: they perform their warm-up laps using nasal breathing only for 2-3 days per week. The team found success not just in getting the boys to comply, but also when they found their pre-practice and pre-game readiness went up dramatically.

Introducing nasal breathing in the warm-up is something I recommend to coaches when starting this with athletes, and it’s something I’ve found great success with in the past. Restricting breathing can be a stressor in and of itself and potentially decrease outputs in the short term. Therefore, it’s essential that you don’t start with something the athlete(s) places high value on, and the warm-up is a great place to get buy-in.

This approach should by no means be relegated to the warm-up only, and nasal breathing during general conditioning activities should be a goal over time. That said, if all training is always nasal breathing, it can rob athletes, especially in a team setting, of opportunities to communicate and build camaraderie. Like any tool, understand what it does and use it when and where appropriate.

Return to Play

Another powerful opportunity to integrate this tool is in return to play (RTP) protocols. There are massive, missed opportunities in RTP in general, and this may be one of the most overlooked pieces of low-hanging fruit there is.

Slow, smooth nasal breathing can be a constraint that keeps athletes from willing themselves through rebuilds in order to get back in action faster. The ability to keep the reins on the breath is a clear and direct line of communication with the deepest part of the nervous system. Using a simple parameter like this creates a real-time dialogue between you, the athlete, and their narrative-free response to treatment/training.

Additionally, using controlled nasal breathing at the reintroduction of progressive workloads can serve as an internal restriction on an athlete’s output during the rebuild. It’s kind of like putting a governor on a motor. You don’t get to go faster until you’ve proven that you’re a good driver. As an addendum to that, working hard while nasal breathing feels like hard work. The confidence of an athlete is directly proportional to how well prepared they feel. This tool gives them a challenge to push up against during rehabilitation to keep their mental edge.

Lastly, nasal breathing is a communication of safety to the deepest parts of the nervous system, which is essential in return to play, and nasal breathing constraints can be an amazing force multiplier for coaches and rehab specialists alike.

If I had a dogecoin for every time I saw a therapist or coach employing a “rehab exercise” while the athlete shook, sweated, and hyperventilated, I’d be a virtual billionaire. The a priori job of the nervous system is to protect us. If we cannot reasonably control breath rate while trying to rebuild a movement skill, the human body will by default build compensatory mechanisms and progress will be blunted.

If we cannot reasonably control breath rate while trying to rebuild a movement skill, the human body will by default build compensatory mechanisms and progress will be blunted. Share on XPlacing breath constraints like nasal breathing during movement reeducation is building two-way communication with the central nervous system. On one hand, it provides an opportunity to listen to what the deepest part of the nervous system is telling us about how it’s perceiving the safety of this movement. On the other, we can coax the nervous system into a place of safety by controlling breathing and thus improve the efficacy of our interventions.

Putting It Together

There are some common pitfalls I’ve experienced and observed over the years that I’d like to share in the hope it will speed up your learning curve with this tool.

- Too much, too fast. Many athletes I’ve worked with who have a hard time sustaining nasal breathing try to maintain the same level of output in spite of the fact that they’ve put a clamp on the exhaust. This can result in wasted training time, sinus damage, and disappointing bewilderment. Work with your physiology, not against it.

- Pushing through blockage. If you have a nasal blockage, like a deviated septum or rhinitis, don’t try to force your way through or shove some device up your nose to artificially open things up. Go slow and let your body adapt over time. If you have a serious blockage that needs medical attention, go see an ENT stat.

Short-term tip for sinusitis sufferers: during warm-ups, hum on the exhale. Research shows humming can help subdue acute nasal inflammation through the release of nitric oxide.

Training your nasal passages for progressive loading is just like any other physiological system. Introduce dosage intelligently, with a clear idea of what outcomes you’re looking for and some benchmarks along the way.

Training your nasal passages for progressive loading is just like any other physiological system. Introduce dosage intelligently, with a clear idea of desired outcomes and some benchmarks. Share on XThe rabbit hole of breathing for performance is both deep and wide. Beginning with nasal breathing is a safe and effective way to engage with this process and get the biggest bang for your buck. Nasal breathing is a powerful tool that can enhance athlete health and performance at nearly zero cost to coaches or athletes. If applied with even minimal attention, there are myriad benefits.

Why not try it? You’re breathing anyway.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

1. Chaitow, Leon. Recognizing and Treating Breathing Pattern Disorders. Pgs. 11–21.

2. Chaitow, Leon. Recognizing and Treating Breathing Pattern Disorders. Pgs. 45–49.

3. Bianchini, AP, Guedes, ZCF, and Vieira, MM. “A study on the relationship between mouth breathing and facial morphological pattern.” Brazilian Journal of Otorhinolaryngology. 2007;73(4):500–505.

4. Maniscalco, M, Sofia, M, Weitzberg, E, et al. “Humming-induced release of nasal nitric oxide for assessment of sinus obstruction in allergic rhinitis: pilot study.” European Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2004;34(8):555-560.

5. Savulich, G, Hezemans, FH, van Ghesel Grothe, S, et al. “Acute anxiety and autonomic arousal induced by CO2 inhalation impairs prefrontal executive functions in healthy humans.” Translational Psychiatry. 2019;9(1):296.